Email

Unemployment Data Update: March 2020 through July 31, 2021

| From | Center for Jobs and the Economy <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Unemployment Data Update: March 2020 through July 31, 2021 |

| Date | August 6, 2021 4:00 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Web Version [link removed] | Update Preferences [link removed] [link removed] Unemployment Data Update: March 2020 through July 31, 2021 Unemployment Insurance Claims

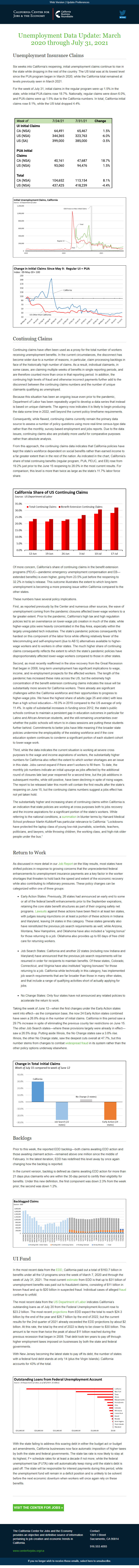

Six weeks into California’s reopening, initial unemployment claims continue to rise in the state while dropping in the rest of the country. The US total was at its lowest level since the PUA program began in March 2020, while the California total remained at levels previously seen in March 2021.

For the week of July 31, initial claims in the regular program were up 1.5% in the state, while initial PUA claims rose 18.7%. Nationally, regular claims were down 6.0%, and PUA claims were up 1.5% due to the California numbers. In total, California initial claims rose 8.1%, while the US total dropped 4.4%.

Continuing Claims

Continuing claims have often been used as a proxy for the total number of workers receiving unemployment benefits. In the current circumstances, the disconnect has become wider due to a number of reasons, in particular, claim processing backlogs in face of the historically high number of claims. As a result, individual claimants, in some cases, are claiming multiple weeks of benefits in single reporting periods, and are therefore counted more than once in that reporting period. In addition, the continuing high levels of fraud and otherwise incorrect payments further add to the disconnect between the continuing claims numbers and the number of unique claimants qualifying as unemployed.

Because this situation has been an ongoing issue even prior to the pandemic, Department of Labor has been repeatedly urged to develop a data series that instead is based on unique claimants. The agency now indicates it is likely to begin producing the data some time in 2022, well beyond the current policy timeframe requirements.

Consequently, while flawed, continuing claims currently remain the primary data source to assess a number of policy questions using more real-time census-type data rather than the monthly, survey-based employment and jobs reports. Due to the data issues, continuing claims also are probably more useful for comparative purposes rather than absolute analysis.

From this approach, the continuing claims data indicates that California policies have kept the state’s workforce dependent on social benefits rather than earned income to a far greater extent than in the rest of the nation. As indicated in the chart, California’s share of total continuing benefits (regular program, PUA, PEUC, and EB) rose from 19.2% just prior to the June 15 reopening to 28.0% in the most current results. For comparison, this level is more than twice as large as the state’s 11.7% labor force share.

Of more concern, California’s share of continuing claims in the benefit extension programs (PEUC—pandemic emergency unemployment compensation and EB—extended benefits) is even higher, going from 23.5% just before the reopening to 32.2% in today’s release. This outcome illustrates the extent to which long-term unemployment is becoming a more pressing issue within California compared to the other states.

These numbers have several policy implications.

First, as reported previously by the Center and numerous other sources, the wave of unemployment coming from the pandemic closures affected lower-wage workers to a far greater extent. Prior to the pandemic, California’s high tax and high regulation policies led to an overreliance on lower-wage job creation in much of the state, while higher-wage jobs were heavily concentrated in the Bay Area, especially within the largely unregulated tech industries. The state’s pandemic policies consequently hit hardest on this component of the labor force while offering relatively fewer of the telecommuting and self-employment (due to AB 5) alternatives available to higher-wage workers and to workers in other states. The much higher share of continuing claims consequently reflects the extent to which the state’s pandemic policies have disproportionately affected lower-wage workers compared to those in other states.

Second, as most recently reaffirmed in the slow recovery from the Great Recession that began in 2008, long-term unemployment has significant implications to wage, income, and re-employment prospects for the affected workers. The length of the pandemic has increased these risks across the US, but the extremely high concentration of the benefit extension continuing claims indicates the issue will be substantially more severe for California workers. There already are significant challenges within the California workforce and their opportunities to progress to higher-wage jobs. We have the highest share of adults (age 25 and older) with less than a high school education—16.0% in 2019 compared to the US average of only 11.4%. In spite of substantial increases in funding since 2012, the state’s public schools continue to maintain a persistent gap in education outcomes in particular for Latino and African-American students, and the still-remaining uncertainties over whether the public schools will return to in-class sessions are putting these students further behind. Commitments to better jobs have little meaning if the broader state policies undermine the employability of the existing workforce and if the core education system continues to condemn a significant portion of each student cohort to lower-wage work.

Third, while the data indicates the current situation is working at severe cross purposes to the wage and income aspirations of workers, the substantially higher numbers for California also reflect the extent to which worker shortages are an issue in this state. Jobs cannot expand if there aren’t workers to fill them. To date, the monthly job numbers indicate an initial upsurge as jobs affected by the additional round of closures late last year reopened for a second time, but the job additions in subsequent months, while still positive, have been declining in spite of rising wages. The report to be released later this month will contain the first results after the state’s reopening on June 15, but the continuing claims numbers suggest a jobs effect has not yet taken hold.

The substantially higher and increasing share of continuing claims within California is an indication that state policies are working at cross purposes both to jobs recovery and the income aspirations for a significant portion of the state’s workers. While referring to the national conditions, a summation [[link removed]] in blunter terms by Harvard Medical School professor Martin Kulldorff has particular relevance to California: “Lockdowns have protected the laptop class of young low-risk journalists, scientists, teachers, politicians, and lawyers, while throwing children, the working class, and high-risk older people under the bus.”

Return to Work

As discussed in more detail in our Job Report [[link removed]] on the May results, most states have shifted policies in response to growing concerns that the unprecedented federal enhancements to unemployment insurance payments are a key factor in the worker shortages that threaten to hold back the speed and extent of the economic recovery while also contributing to inflationary pressures. These policy changes can be categorized within one of three groups:

Early Action States: Previously, 26 states had announced an early end to some or all of the federal benefit enhancements prior to the September expirations, retaining the core state benefit structures as part of their ongoing safety net programs. Lawsuits [[link removed]] against these actions have been filed in at least ten states, with judges issuing injunctions on at least a portion of these actions in Indiana and Maryland, leaving 24 states in this category. These states generally also have reinstituted the previous job search requirements as well, while Arizona, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma have also included a “signing bonus” for those returning to a job. Oklahoma also provides up to 60 days of free child care for returning workers.

Job Search States: California and another 22 states (including now Indiana and Maryland) have announced that the previous job search requirements will be resumed in order for recipients to maintain benefits. Of these states, Colorado, Connecticut, and Virginia have also instituted “signing bonuses” for those returning to a job. California while technically in this category, has implemented job search requirements that are far broader than those in many other states, and that include a range of qualifying activities short of actually applying for jobs.

No Change States: Only four states have not announced any related policies to accelerate the return to work.

Taking the week of June 12—when the first changes under the Early Action states went into effect—as the comparison base, the now 24 Early Action states combined have seen a 26.8% drop in the number of initial claims. California in this period saw a 29.7% increase in spite of eliminating the previous county tier restrictions on June 15. The other Job Search states—where these provisions largely were already in effect—saw a 26.5% drop. Putting aside Illinois, the No Change states saw a 3.8% rise. Illinois, the other No Change state, saw the deepest cuts overall at 47.7%, but this number stems from changes to combat widespread fraud [[link removed]] in its system rather than the other policy options underway elsewhere.

Backlogs

Prior to this week, the reported EDD backlog—both claims awaiting EDD action and those awaiting claimant action—remained above one million since the middle of February. In the latest iteration, EDD has redefined this level away by once again changing how the backlog is reported.

In the current version, backlog is defined as claims awaiting EDD action for more than 21 days plus claimants who are within the 30-day period to certify their eligibility for benefits. Under this new definition, the first component was down 2.3% from the week prior; the second was down 1.2%.

UI Fund

In the most recent data from the EDD [[link removed]], California paid out a total of $163.7 billion in benefits under all the UI programs since the week of March 7, 2020 and through the week of July 31, 2021. The most current estimate [[link removed]] from EDD is that up to $31 billion of unemployment benefits was paid out to fraudulent claims, consisting of $11 billion in known fraud and up to $20 billion in suspected fraud. Individual cases of alleged fraud [[link removed]] continue to unfold.

The most recent data from the US Department of Labor [[link removed]] indicates California’s outstanding loans as of July 20 from the Federal Unemployment Account rose to $23.2 billion. The most recent projections [[link removed]] from EDD expect the total to reach $24.3 billion by the end of the year and $26.7 billion by the end of 2022, but the current results for the 2nd quarter of 2021 already exceeded the EDD projections by about $2 billion. At this rate, the total by the end of 2022 is likely to be closer to $30 billion. This amount is far more than twice the peak of about $11 billion reached during the previous recession that began in 2008. That debt took ten years to pay off through higher employment taxes imposed on businesses by both the state and federal governments.

With New Jersey becoming the latest state to pay off its debt, the number of states with a federal fund debt stands at only 14 (plus the Virgin Islands). California accounts for 43% of the total.

With the state failing to address this soaring debt in either the budget act or budget act amendments, California businesses now face automatic imposition of higher taxes by both the state and federal governments. The state tax rate is now likely to stay at its highest, F+ schedule rates for at least a decade if not more, while the federal unemployment tax (FUTA) rate will automatically keep rising until the state’s debt is paid off. The state will be responsible for interest payments during this period, while the unemployment fund will remain in a deficit position and is unlikely to be solvent before the next economic downturn when workers will once again rely on these benefits.

visit the center for jobs » [[link removed]] The California Center for Jobs and the Economy provides an objective and definitive source of information pertaining to job creation and economic trends in California. [[link removed]] Contact 1301 I Street Sacramento, CA 95814 916.553.4093 If you no longer wish to receive these emails, select here to unsubscribe. [link removed]

Six weeks into California’s reopening, initial unemployment claims continue to rise in the state while dropping in the rest of the country. The US total was at its lowest level since the PUA program began in March 2020, while the California total remained at levels previously seen in March 2021.

For the week of July 31, initial claims in the regular program were up 1.5% in the state, while initial PUA claims rose 18.7%. Nationally, regular claims were down 6.0%, and PUA claims were up 1.5% due to the California numbers. In total, California initial claims rose 8.1%, while the US total dropped 4.4%.

Continuing Claims

Continuing claims have often been used as a proxy for the total number of workers receiving unemployment benefits. In the current circumstances, the disconnect has become wider due to a number of reasons, in particular, claim processing backlogs in face of the historically high number of claims. As a result, individual claimants, in some cases, are claiming multiple weeks of benefits in single reporting periods, and are therefore counted more than once in that reporting period. In addition, the continuing high levels of fraud and otherwise incorrect payments further add to the disconnect between the continuing claims numbers and the number of unique claimants qualifying as unemployed.

Because this situation has been an ongoing issue even prior to the pandemic, Department of Labor has been repeatedly urged to develop a data series that instead is based on unique claimants. The agency now indicates it is likely to begin producing the data some time in 2022, well beyond the current policy timeframe requirements.

Consequently, while flawed, continuing claims currently remain the primary data source to assess a number of policy questions using more real-time census-type data rather than the monthly, survey-based employment and jobs reports. Due to the data issues, continuing claims also are probably more useful for comparative purposes rather than absolute analysis.

From this approach, the continuing claims data indicates that California policies have kept the state’s workforce dependent on social benefits rather than earned income to a far greater extent than in the rest of the nation. As indicated in the chart, California’s share of total continuing benefits (regular program, PUA, PEUC, and EB) rose from 19.2% just prior to the June 15 reopening to 28.0% in the most current results. For comparison, this level is more than twice as large as the state’s 11.7% labor force share.

Of more concern, California’s share of continuing claims in the benefit extension programs (PEUC—pandemic emergency unemployment compensation and EB—extended benefits) is even higher, going from 23.5% just before the reopening to 32.2% in today’s release. This outcome illustrates the extent to which long-term unemployment is becoming a more pressing issue within California compared to the other states.

These numbers have several policy implications.

First, as reported previously by the Center and numerous other sources, the wave of unemployment coming from the pandemic closures affected lower-wage workers to a far greater extent. Prior to the pandemic, California’s high tax and high regulation policies led to an overreliance on lower-wage job creation in much of the state, while higher-wage jobs were heavily concentrated in the Bay Area, especially within the largely unregulated tech industries. The state’s pandemic policies consequently hit hardest on this component of the labor force while offering relatively fewer of the telecommuting and self-employment (due to AB 5) alternatives available to higher-wage workers and to workers in other states. The much higher share of continuing claims consequently reflects the extent to which the state’s pandemic policies have disproportionately affected lower-wage workers compared to those in other states.

Second, as most recently reaffirmed in the slow recovery from the Great Recession that began in 2008, long-term unemployment has significant implications to wage, income, and re-employment prospects for the affected workers. The length of the pandemic has increased these risks across the US, but the extremely high concentration of the benefit extension continuing claims indicates the issue will be substantially more severe for California workers. There already are significant challenges within the California workforce and their opportunities to progress to higher-wage jobs. We have the highest share of adults (age 25 and older) with less than a high school education—16.0% in 2019 compared to the US average of only 11.4%. In spite of substantial increases in funding since 2012, the state’s public schools continue to maintain a persistent gap in education outcomes in particular for Latino and African-American students, and the still-remaining uncertainties over whether the public schools will return to in-class sessions are putting these students further behind. Commitments to better jobs have little meaning if the broader state policies undermine the employability of the existing workforce and if the core education system continues to condemn a significant portion of each student cohort to lower-wage work.

Third, while the data indicates the current situation is working at severe cross purposes to the wage and income aspirations of workers, the substantially higher numbers for California also reflect the extent to which worker shortages are an issue in this state. Jobs cannot expand if there aren’t workers to fill them. To date, the monthly job numbers indicate an initial upsurge as jobs affected by the additional round of closures late last year reopened for a second time, but the job additions in subsequent months, while still positive, have been declining in spite of rising wages. The report to be released later this month will contain the first results after the state’s reopening on June 15, but the continuing claims numbers suggest a jobs effect has not yet taken hold.

The substantially higher and increasing share of continuing claims within California is an indication that state policies are working at cross purposes both to jobs recovery and the income aspirations for a significant portion of the state’s workers. While referring to the national conditions, a summation [[link removed]] in blunter terms by Harvard Medical School professor Martin Kulldorff has particular relevance to California: “Lockdowns have protected the laptop class of young low-risk journalists, scientists, teachers, politicians, and lawyers, while throwing children, the working class, and high-risk older people under the bus.”

Return to Work

As discussed in more detail in our Job Report [[link removed]] on the May results, most states have shifted policies in response to growing concerns that the unprecedented federal enhancements to unemployment insurance payments are a key factor in the worker shortages that threaten to hold back the speed and extent of the economic recovery while also contributing to inflationary pressures. These policy changes can be categorized within one of three groups:

Early Action States: Previously, 26 states had announced an early end to some or all of the federal benefit enhancements prior to the September expirations, retaining the core state benefit structures as part of their ongoing safety net programs. Lawsuits [[link removed]] against these actions have been filed in at least ten states, with judges issuing injunctions on at least a portion of these actions in Indiana and Maryland, leaving 24 states in this category. These states generally also have reinstituted the previous job search requirements as well, while Arizona, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma have also included a “signing bonus” for those returning to a job. Oklahoma also provides up to 60 days of free child care for returning workers.

Job Search States: California and another 22 states (including now Indiana and Maryland) have announced that the previous job search requirements will be resumed in order for recipients to maintain benefits. Of these states, Colorado, Connecticut, and Virginia have also instituted “signing bonuses” for those returning to a job. California while technically in this category, has implemented job search requirements that are far broader than those in many other states, and that include a range of qualifying activities short of actually applying for jobs.

No Change States: Only four states have not announced any related policies to accelerate the return to work.

Taking the week of June 12—when the first changes under the Early Action states went into effect—as the comparison base, the now 24 Early Action states combined have seen a 26.8% drop in the number of initial claims. California in this period saw a 29.7% increase in spite of eliminating the previous county tier restrictions on June 15. The other Job Search states—where these provisions largely were already in effect—saw a 26.5% drop. Putting aside Illinois, the No Change states saw a 3.8% rise. Illinois, the other No Change state, saw the deepest cuts overall at 47.7%, but this number stems from changes to combat widespread fraud [[link removed]] in its system rather than the other policy options underway elsewhere.

Backlogs

Prior to this week, the reported EDD backlog—both claims awaiting EDD action and those awaiting claimant action—remained above one million since the middle of February. In the latest iteration, EDD has redefined this level away by once again changing how the backlog is reported.

In the current version, backlog is defined as claims awaiting EDD action for more than 21 days plus claimants who are within the 30-day period to certify their eligibility for benefits. Under this new definition, the first component was down 2.3% from the week prior; the second was down 1.2%.

UI Fund

In the most recent data from the EDD [[link removed]], California paid out a total of $163.7 billion in benefits under all the UI programs since the week of March 7, 2020 and through the week of July 31, 2021. The most current estimate [[link removed]] from EDD is that up to $31 billion of unemployment benefits was paid out to fraudulent claims, consisting of $11 billion in known fraud and up to $20 billion in suspected fraud. Individual cases of alleged fraud [[link removed]] continue to unfold.

The most recent data from the US Department of Labor [[link removed]] indicates California’s outstanding loans as of July 20 from the Federal Unemployment Account rose to $23.2 billion. The most recent projections [[link removed]] from EDD expect the total to reach $24.3 billion by the end of the year and $26.7 billion by the end of 2022, but the current results for the 2nd quarter of 2021 already exceeded the EDD projections by about $2 billion. At this rate, the total by the end of 2022 is likely to be closer to $30 billion. This amount is far more than twice the peak of about $11 billion reached during the previous recession that began in 2008. That debt took ten years to pay off through higher employment taxes imposed on businesses by both the state and federal governments.

With New Jersey becoming the latest state to pay off its debt, the number of states with a federal fund debt stands at only 14 (plus the Virgin Islands). California accounts for 43% of the total.

With the state failing to address this soaring debt in either the budget act or budget act amendments, California businesses now face automatic imposition of higher taxes by both the state and federal governments. The state tax rate is now likely to stay at its highest, F+ schedule rates for at least a decade if not more, while the federal unemployment tax (FUTA) rate will automatically keep rising until the state’s debt is paid off. The state will be responsible for interest payments during this period, while the unemployment fund will remain in a deficit position and is unlikely to be solvent before the next economic downturn when workers will once again rely on these benefits.

visit the center for jobs » [[link removed]] The California Center for Jobs and the Economy provides an objective and definitive source of information pertaining to job creation and economic trends in California. [[link removed]] Contact 1301 I Street Sacramento, CA 95814 916.553.4093 If you no longer wish to receive these emails, select here to unsubscribe. [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: California Center for Jobs and the Economy

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: California

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor