Email

Critical minerals - as good as gold?

| From | Climate. Change. | Context <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Critical minerals - as good as gold? |

| Date | August 19, 2025 12:00 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View Online [[link removed]] | Subscribe now [[link removed]]Journalism from theKnow better. Do better.Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world

By Jack Graham | Climate Journalist

Caves and mudslides

In the forested mountains a few hours from Jakarta, Indonesia, my colleagues Leo Galuh and Mas Agung Wilis Yudha Baskoro had a day they would rather forget.

Nearing the hamlet of Citorek Kidul in the night, the pair encountered a mudslide on the road. The wheels of their car came perilously close to the cliff edge before they were rescued by locals as heavy rain bucketed down.

Reporting in these mountains, Leo and Yudha would hear many similar stories of danger from illegal gold miners who risk life and limb [[link removed]] to burrow more than 100 metres into mountains and caves.

The two most populous countries in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines, are sitting on vast reserves of valuable commodities [[link removed]], from gold to nickel. [[link removed]]

Demand is higher than ever [[link removed]] thanks to record gold prices and the need for critical minerals to power the clean energy transition, needed to make electric vehicles and wind turbines.

But these countries are also megadiverse hotspots, housing some of the world's most important natural environments like rainforests and coastal mangroves.

A mine worker carries a sack filled with rock chunks suspected to contain gold in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro

To understand how this is playing out, I spoke to Michaela G.Y. Lo, an expert on development and conservation in Indonesia. She warned against people getting "swept away" with the narrative of cutting greenhouse gas emissions without considering the impacts of mining.

"Greater accountability of what's happening locally I think is crucial," said Lo, who works at the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, and recently led research into more than 7,000 villages in the nickel-producing Indonesian island, Sulawesi.

Published last year, it showed that deforestation nearly doubled [[link removed](24)00534-7?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=context-climate] between 2011 and 2018 in nickel-mining villages, but improvements in living standards tended to be outweighed by environmental damages like pollution, especially in high poverty areas, such as fishing villages. [[link removed](24)00534-7?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=context-climate]

And in remote Citorek Kidul, even small-scale illegal gold mining can leave its mark on the land. Local agricultural officer Sukmadi Jaya Rukmana told Leo that uncontrolled mining could increase the risk of deadly landslides.

"The green vegetation around the mountains is stripped away, leaving rainwater to rush downhill without any natural buffer," Lo told me.

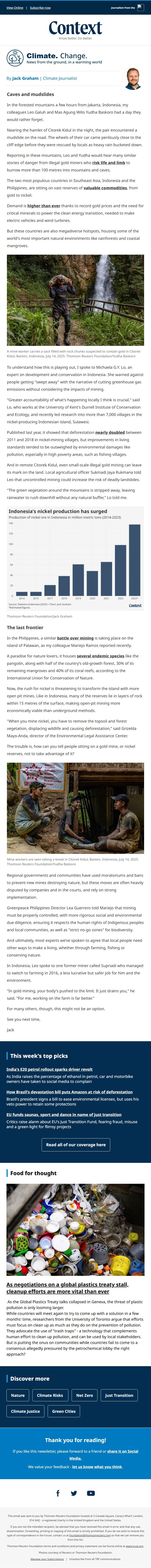

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

The last frontier

In the Philippines, a similar battle over mining [[link removed]] is taking place on the island of Palawan, as my colleague Mariejo Ramos reported recently. [[link removed]]

A paradise for nature lovers, it houses several endemic species [[link removed]] like the pangolin, along with half of the country’s old-growth forest, 30% of its remaining mangroves and 40% of its coral reefs, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Now, the rush for nickel is threatening to transform the island with more open pit mines. Like in Indonesia, many of the reserves lie in layers of rock within 15 metres of the surface, making open-pit mining more economically viable than underground methods.

"When you mine nickel, you have to remove the topsoil and forest vegetation, displacing wildlife and causing deforestation,” said Grizelda Mayo-Anda, director of the Environmental Legal Assistance Center.

The trouble is, how can you tell people sitting on a gold mine, or nickel reserves, not to take advantage of it?

Mine workers are seen taking a break in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro

Regional governments and communities have used moratoriums and bans to prevent new mines destroying nature, but these moves are often heavily disputed by companies and in the courts, and rely on strong implementation.

Greenpeace Philippines Director Lea Guerrero told Mariejo that mining must be properly controlled, with more rigorous social and environmental due diligence, ensuring it respects the human rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as "strict no-go zones" for biodiversity.

And ultimately, most experts we’ve spoken to agree that local people need other ways to make a living, whether through farming, fishing or conserving nature.

In Indonesia, Leo spoke to one former miner called Supriadi who managed to switch to farming in 2016, a less lucrative but safer job for him and the environment.

"In gold mining, your body's pushed to the limit. It just drains you," he said. "For me, working on the farm is far better."

For many others, though, this might not be an option.

See you next time,

Jack

This week's top picks India's E20 petrol rollout sparks driver revolt [[link removed]]

As India raises the percentage of ethanol in petrol, car and motorbike owners have taken to social media to complain

How Brazil's devastation bill puts Amazon at risk of deforestation [[link removed]]

Brazil's president signs a bill to ease environmental licenses, but uses his veto power to retain some protections

EU funds saunas, sport and dance in name of just transition [[link removed]]

Critics raise alarm about EU's Just Transition Fund, fearing fraud, misuse and a green light for flimsy projects

Read all of our coverage here [[link removed]] Food for thought [[link removed]] As negotiations on a global plastics treaty stall, cleanup efforts are more vital than ever [[link removed]]

As the Global Plastics Treaty talks collapsed in Geneva, the threat of plastic pollution is only looming larger.

While countries will meet again to try to come up with a solution in a few months' time, researchers from the University of Toronto argue that efforts must focus on clean up as much as they do on the prevention of pollution.

They advocate the use of "trash traps" - a technology that complements human effort to clean up pollution, and can be used by local stakeholders. But is putting the onus on communities while countries fail to come to a consensus allegedly pressured by the petrochemical lobby the right approach?

[[link removed]]Discover more Nature [[link removed]] Climate Risks [[link removed]] Net Zero [[link removed]] Just Transition [[link removed]] Climate Justice [[link removed]] Green Cities [[link removed]] Thank you for reading!

If you like this newsletter, please forward to a friend or share it on Social Media. [[link removed]]

We value your feedback - let us know what you think [mailto:[email protected]].

[[link removed]]

This email was sent to you by Thomson Reuters Foundation located at 5 Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London, E14 5AQ - a registered charity in the United Kingdom and the United States.

If you are not the intended recipient, be advised that you have received this email in error and that any use, dissemination, forwarding, printing or copying of this email is strictly prohibited. If you do not wish to receive this type of correspondence in the future, contact us at [[email protected]] so that we can remove you from this list.

Thomson Reuters Foundation terms and conditions and privacy statement can be found online at www.trust.org [[link removed]].

Photos courtesy of Reuters or Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Manage your Subscriptions [[link removed]] | Unsubscribe from all TRF communications [link removed]

By Jack Graham | Climate Journalist

Caves and mudslides

In the forested mountains a few hours from Jakarta, Indonesia, my colleagues Leo Galuh and Mas Agung Wilis Yudha Baskoro had a day they would rather forget.

Nearing the hamlet of Citorek Kidul in the night, the pair encountered a mudslide on the road. The wheels of their car came perilously close to the cliff edge before they were rescued by locals as heavy rain bucketed down.

Reporting in these mountains, Leo and Yudha would hear many similar stories of danger from illegal gold miners who risk life and limb [[link removed]] to burrow more than 100 metres into mountains and caves.

The two most populous countries in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines, are sitting on vast reserves of valuable commodities [[link removed]], from gold to nickel. [[link removed]]

Demand is higher than ever [[link removed]] thanks to record gold prices and the need for critical minerals to power the clean energy transition, needed to make electric vehicles and wind turbines.

But these countries are also megadiverse hotspots, housing some of the world's most important natural environments like rainforests and coastal mangroves.

A mine worker carries a sack filled with rock chunks suspected to contain gold in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro

To understand how this is playing out, I spoke to Michaela G.Y. Lo, an expert on development and conservation in Indonesia. She warned against people getting "swept away" with the narrative of cutting greenhouse gas emissions without considering the impacts of mining.

"Greater accountability of what's happening locally I think is crucial," said Lo, who works at the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, and recently led research into more than 7,000 villages in the nickel-producing Indonesian island, Sulawesi.

Published last year, it showed that deforestation nearly doubled [[link removed](24)00534-7?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=context-climate] between 2011 and 2018 in nickel-mining villages, but improvements in living standards tended to be outweighed by environmental damages like pollution, especially in high poverty areas, such as fishing villages. [[link removed](24)00534-7?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=context-climate]

And in remote Citorek Kidul, even small-scale illegal gold mining can leave its mark on the land. Local agricultural officer Sukmadi Jaya Rukmana told Leo that uncontrolled mining could increase the risk of deadly landslides.

"The green vegetation around the mountains is stripped away, leaving rainwater to rush downhill without any natural buffer," Lo told me.

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

The last frontier

In the Philippines, a similar battle over mining [[link removed]] is taking place on the island of Palawan, as my colleague Mariejo Ramos reported recently. [[link removed]]

A paradise for nature lovers, it houses several endemic species [[link removed]] like the pangolin, along with half of the country’s old-growth forest, 30% of its remaining mangroves and 40% of its coral reefs, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Now, the rush for nickel is threatening to transform the island with more open pit mines. Like in Indonesia, many of the reserves lie in layers of rock within 15 metres of the surface, making open-pit mining more economically viable than underground methods.

"When you mine nickel, you have to remove the topsoil and forest vegetation, displacing wildlife and causing deforestation,” said Grizelda Mayo-Anda, director of the Environmental Legal Assistance Center.

The trouble is, how can you tell people sitting on a gold mine, or nickel reserves, not to take advantage of it?

Mine workers are seen taking a break in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro

Regional governments and communities have used moratoriums and bans to prevent new mines destroying nature, but these moves are often heavily disputed by companies and in the courts, and rely on strong implementation.

Greenpeace Philippines Director Lea Guerrero told Mariejo that mining must be properly controlled, with more rigorous social and environmental due diligence, ensuring it respects the human rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as "strict no-go zones" for biodiversity.

And ultimately, most experts we’ve spoken to agree that local people need other ways to make a living, whether through farming, fishing or conserving nature.

In Indonesia, Leo spoke to one former miner called Supriadi who managed to switch to farming in 2016, a less lucrative but safer job for him and the environment.

"In gold mining, your body's pushed to the limit. It just drains you," he said. "For me, working on the farm is far better."

For many others, though, this might not be an option.

See you next time,

Jack

This week's top picks India's E20 petrol rollout sparks driver revolt [[link removed]]

As India raises the percentage of ethanol in petrol, car and motorbike owners have taken to social media to complain

How Brazil's devastation bill puts Amazon at risk of deforestation [[link removed]]

Brazil's president signs a bill to ease environmental licenses, but uses his veto power to retain some protections

EU funds saunas, sport and dance in name of just transition [[link removed]]

Critics raise alarm about EU's Just Transition Fund, fearing fraud, misuse and a green light for flimsy projects

Read all of our coverage here [[link removed]] Food for thought [[link removed]] As negotiations on a global plastics treaty stall, cleanup efforts are more vital than ever [[link removed]]

As the Global Plastics Treaty talks collapsed in Geneva, the threat of plastic pollution is only looming larger.

While countries will meet again to try to come up with a solution in a few months' time, researchers from the University of Toronto argue that efforts must focus on clean up as much as they do on the prevention of pollution.

They advocate the use of "trash traps" - a technology that complements human effort to clean up pollution, and can be used by local stakeholders. But is putting the onus on communities while countries fail to come to a consensus allegedly pressured by the petrochemical lobby the right approach?

[[link removed]]Discover more Nature [[link removed]] Climate Risks [[link removed]] Net Zero [[link removed]] Just Transition [[link removed]] Climate Justice [[link removed]] Green Cities [[link removed]] Thank you for reading!

If you like this newsletter, please forward to a friend or share it on Social Media. [[link removed]]

We value your feedback - let us know what you think [mailto:[email protected]].

[[link removed]]

This email was sent to you by Thomson Reuters Foundation located at 5 Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London, E14 5AQ - a registered charity in the United Kingdom and the United States.

If you are not the intended recipient, be advised that you have received this email in error and that any use, dissemination, forwarding, printing or copying of this email is strictly prohibited. If you do not wish to receive this type of correspondence in the future, contact us at [[email protected]] so that we can remove you from this list.

Thomson Reuters Foundation terms and conditions and privacy statement can be found online at www.trust.org [[link removed]].

Photos courtesy of Reuters or Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Manage your Subscriptions [[link removed]] | Unsubscribe from all TRF communications [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor