| Know better. Do better. |  | Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world |

|

| | | By Jack Graham | Climate Journalist | | |

|  |

| Caves and mudslidesIn the forested mountains a few hours from Jakarta, Indonesia, my colleagues Leo Galuh and Mas Agung Wilis Yudha Baskoro had a day they would rather forget.

Nearing the hamlet of Citorek Kidul in the night, the pair encountered a mudslide on the road. The wheels of their car came perilously close to the cliff edge before they were rescued by locals as heavy rain bucketed down.

Reporting in these mountains, Leo and Yudha would hear many similar stories of danger from illegal gold miners who risk life and limb to burrow more than 100 metres into mountains and caves.

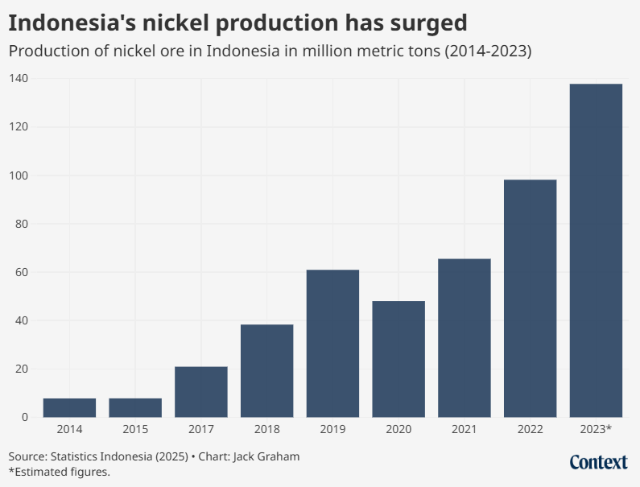

The two most populous countries in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines, are sitting on vast reserves of valuable commodities, from gold to nickel.

Demand is higher than ever thanks to record gold prices and the need for critical minerals to power the clean energy transition, needed to make electric vehicles and wind turbines.

But these countries are also megadiverse hotspots, housing some of the world's most important natural environments like rainforests and coastal mangroves.  A mine worker carries a sack filled with rock chunks suspected to contain gold in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro |

To understand how this is playing out, I spoke to Michaela G.Y. Lo, an

expert on development and conservation in Indonesia. She warned against people getting "swept away" with the narrative of cutting greenhouse gas emissions without considering the impacts of mining.

"Greater accountability of what's happening locally I think is crucial," said Lo, who works at the University of Kent's Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, and recently led research into more than 7,000 villages in the nickel-producing Indonesian island, Sulawesi.

Published last year, it showed that deforestation nearly doubled between 2011 and 2018 in nickel-mining villages, but improvements in living standards tended to be outweighed by environmental damages like pollution, especially in high poverty areas, such as fishing villages.

And in remote Citorek Kidul, even small-scale illegal gold mining can leave its mark on the land. Local agricultural officer Sukmadi Jaya Rukmana told Leo that uncontrolled mining could increase the risk of deadly landslides.

"The green vegetation around the mountains is stripped away, leaving rainwater to rush downhill without any natural buffer," Lo told me.  Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham |

The last frontierIn the Philippines, a similar battle over mining is taking place on the island of Palawan, as my colleague Mariejo Ramos reported recently.

A paradise for nature lovers, it houses several endemic species like the pangolin, along with half of the country’s old-growth forest, 30% of its remaining mangroves and 40% of its coral reefs, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Now, the rush for nickel is threatening to transform the island with more open pit mines. Like in Indonesia, many of the reserves lie in layers of rock within 15 metres of the surface, making open-pit mining more economically viable than underground methods.

"When you mine nickel, you have to remove the topsoil and forest vegetation, displacing wildlife and causing deforestation,” said Grizelda Mayo-Anda, director of the Environmental Legal Assistance Center.

The trouble is, how can you tell people sitting on a gold mine, or nickel reserves, not to take advantage of it?  Mine workers are seen taking a break in Citorek Kidul, Banten, Indonesia, July 14, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Yudha Baskoro |

Regional governments and communities have used moratoriums and bans to prevent new mines destroying nature, but these moves are often heavily disputed by companies and in the courts, and rely on strong

implementation.

Greenpeace Philippines Director Lea Guerrero told Mariejo that mining must be properly controlled, with more rigorous social and environmental due diligence, ensuring it respects the human rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as "strict no-go zones" for biodiversity.

And ultimately, most experts we’ve spoken to agree that local people need other ways to make a living, whether through farming, fishing or conserving nature.

In Indonesia, Leo spoke to one former miner called Supriadi who managed to switch to farming in 2016, a less lucrative but safer job for him and the environment.

"In gold mining, your body's pushed to the limit. It just drains you," he said. "For me, working on the farm is far better."

For many others, though, this might not be an option.

See you next time,

Jack |

|

|

|