Email

NEW 50-STATE REPORT: The rapid & unregulated growth of e-messaging in prison

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW 50-STATE REPORT: The rapid & unregulated growth of e-messaging in prison |

| Date | March 28, 2023 2:46 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

E-messaging is the latest way companies are sapping funds from incarcerated people & their families.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for March 28, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

SMH: The rapid & unregulated growth of e- messaging in prisons [[link removed]] A technology that, until recently, was new in prisons and jails has exploded in popularity in recent years. Our review found that, despite its potential to keep incarcerated people and their families connected, e-messaging has quickly become just another way for companies to profit at their expense. [[link removed]]

by Mike Wessler

Over the last twenty years, advocates and regulators have successfully lowered the prices of prison and jail phone rates. While these victories garnered headlines and attention, the companies behind these services quietly regrouped and refocused their efforts. Seeking different ways to protect their profits, they entered less-regulated industries and offered new products to people behind bars. One new service in particular — text-based electronic messaging or “e-messaging” — has experienced explosive and unregulated growth. As a result, rather than living up to its potential as a way to maintain connections between people in prison and the outside world — something that benefits all of us [[link removed]] — high costs and shoddy technology have made e-messaging little more than the latest way these companies drain money from incarcerated people and their loved ones.

In 2016, we released a groundbreaking report [[link removed]] that took a first look at e-messaging, sometimes — but incorrectly — called “email.” At that time, the technology was experimental, untested, and viewed skeptically by many correctional administrators. Since then, though, it has become common inside prison walls.

To better understand this explosive growth in e-messaging, we examined all 50 state prison systems, as well as the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), to see how common this technology has become, how much it costs, and what, if anything, is being done to protect incarcerated people and their families from exploitation. We found an industry that is in flux, expanding quickly, and has yet to face the legislative and regulatory oversight it desperately needs.

The explosive growth of e-messaging in prisons

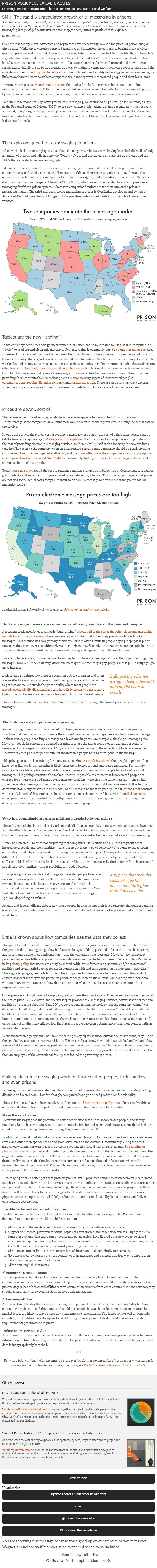

When we looked at e-messaging in 2016, the technology was relatively new, having broached the walls of only a handful of prisons and jails nationwide. Today, we’ve found that at least 43 state prison systems and the BOP offer some electronic messaging option.

Like most prison communications services, e-messaging is dominated by just a few corporations. One company has established a particularly firm grasp on this market: Securus, under its “JPay” brand. The company serves half of the prison systems that offer e-messaging, holding contracts in 22 states. The other dominant company in the space, Global Tel*Link (GTL), which recently rebranded to ViaPath, provides e-messaging for fifteen prison systems. These two companies dominate more than 81% of the prison e-messaging market. The third most common e-messaging provider is CorrLinks, developed and owned by Advanced Technologies Group, LLC (part of the private-equity-owned Keefe Group family of correctional vendors).

Tablets are the new “it thing.”

In the early days of the technology, incarcerated users often had to wait in line to use a shared computer (or “kiosk”) to read or send electronic messages. Now messaging is commonly part of a computer tablet [[link removed]] package, where each incarcerated user is either assigned their own tablet or checks one out for a set period of time. In terms of usability, this is good news (no one should have to write a letter home with a line of impatient people waiting behind them). But serious questions about the economics of tablet programs remain. These tablets are often touted as “free” but, in reality, are rife with hidden costs [[link removed]]. The Covid-19 pandemic has been an economic boon [[link removed]] for the companies that operate these programs, yet as tablets become more common, the companies providing them continue their relentless push to monetize [[link removed]] every aspect of incarcerated peoples’ communications [[link removed]], reading [[link removed]], listening to music [[link removed]], and formal education [[link removed]]. There are also grave privacy concerns when one company controls all communications channels to which incarcerated people have access.

Prices are down…sort of

The per-message price of sending an electronic message appears to have inched down since 2016. Unfortunately, some companies have found new ways to maximize their profits while hiding the actual cost of the service.

In our 2016 survey, the typical cost of sending a message was roughly the cost of a first-class postage stamp (at the time, a stamp was 49¢). We’ve previously explained [[link removed].] that the price of a stamp has nothing to do with the cost of providing electronic messaging services, so there is little justification for tying the two products together. The costs to the company when an incarcerated person sends a message should be nearly nothing considering it requires no paper or staff labor, and the many other ways the companies already make up the cost of providing their so-called “free” tablets [[link removed]]. Fortunately, linking the price of an e-message to the cost of a stamp has become less prevalent.

Today, our rate survey [[link removed]] found the cost to send an e-message ranges from being free in Connecticut to a high of 50¢ in Alaska and Arkansas, with prices most often between 27¢ to 30¢. This wide range suggests that prices are not tied to the actual costs companies incur to transmit a message but rather set at the point that will maximize profits.

For detailed pricing information for each state, see this report's appendix on our website [[link removed]].

Bulk-pricing schemes are common, confusing, and harm the poorest people

A frequent tactic used by companies is “bulk-pricing.” About half of the states that offer electronic messaging include bulk-pricing schemes [[link removed]], where customers pay a higher cost unless they prepay for larger blocks of messages. This method has two primary problems: First, it often results in people buying large packages of messages they may never use, ultimately wasting their money. Second, it charges the poorest people in prison — people who can only afford a small number of messages at a given time — the most money.

For example, in Alaska, if someone has the money to purchase 40 messages at once, they’ll pay $14 or 35¢ per message. However, if they can only afford one message at a time, they’ll pay 50¢ per message — a roughly 43% price increase.

Bulk-pricing schemes are effectively a fee paid only by the poorest people.

Bulk pricing structures like these are common outside of prison and often are an effective way for businesses to sell their products and for consumers to get discounts. But, inside the prison walls, where most people are already economically disadvantaged [[link removed]] and have little means to earn money [[link removed]], bulk-pricing schemes are effectively a fee paid only by the poorest people.

These schemes invite the question: Why don’t these companies charge the lowest price possible for every message?

The hidden costs of per-minute pricing

Per-messaging pricing only tells a part of the story, however. Some states use a more complex pricing structure that can dramatically increase the amount people pay, and companies earn from a single message. In these states, people sending a message to a loved one in prison are charged a simple per-message price. However, people in prisons are charged per minute to use the tablet computer to read and respond to messages. For example, in Delaware, GTL/ViaPath charges people on the outside 25¢ to send a message. However, it costs 5¢ center per minute for incarcerated people to read or respond to the message.

This pricing structure is troubling for many reasons. First, research has shown [[link removed]] that people in prison often have lower literacy levels, meaning it likely takes them longer to send and read e-messages. Per-minute pricing acts as a literacy tax, making it far more expensive for people who struggle to read and respond to messages. This pricing structure also makes it nearly impossible to assess what incarcerated people are charged for e-messaging and means companies are profiting twice off of the same message — once when someone sends a message to their loved one in prison and again when that loved one reads it. It is hard to determine how many prisons use this model, but it seems to be most frequently used in prisons that contract with GTL/ViaPath. This complex pricing structure is one of the many problems with “ bundled contracts [[link removed]],” which give one company control over multiple services in a prison, allowing them to evade oversight and develop new hidden ways to sap money from incarcerated people.

Waiving commissions, unsurprisingly, leads to lower prices

Through years of abusive practices by prison and jail phone companies, many correctional systems developed an unhealthy reliance on “site commissions,” or kickbacks, to make money off incarcerated people and their families. These commissions have, unfortunately, spilled over into other services, like electronic messaging.

It may be distasteful, but it is not surprising that companies like Securus and GTL seek to profit off of incarcerated people and their families — like it or not, it is the type of behavior we’ve come to expect from corporations and why strong regulatory oversight is needed in this space. Our expectations of government are different, however. Governments should be in the business of serving people, not profiting off of their suffering. This is why these kickbacks are such a problem. They unnecessarily drain money from incarcerated people and their families without providing any added benefit.

Any price that includes kickbacks for the government is higher than it needs to be.Unsurprisingly, among states that charge incarcerated people to send e-messages, prison systems that say they do not receive site-commission revenue have some of the lowest prices. For example, the Illinois Department of Corrections only charges 15¢ per message, and the New York Department of Corrections & Community Supervision charges 15¢-20¢, depending on volume.

As state and federal officials debate how much people in prisons and their loved ones are charged for sending e-messages, they should remember that any price that includes kickbacks for the government is higher than it needs to be.

Little is known about how companies use the data they collect

The quantity and sensitivity of information captured in e-messaging systems — from people on both sides of the prison walls — is staggering. They hold two main types of data, personal information — such as names, addresses, and payment card information — and the contents of the messages. However, the technology providers have done little to explain how users’ data is stored, protected, and used. For example, JPay states in its privacy policy [[link removed]] that users’ data may be shared “with law enforcement personnel and/or correctional facilities and certain third parties for use in connection with and in support of law enforcement activities.” This vague language gives wide latitude to the companies but few answers to users. By using the product, customers (whether they’re the person in prison or the person on the outside) are handing over their data without knowing who can see it, how they can use it, or what protections are in place to ensure it isn’t improperly accessed.

Other providers, though, are not simply vague about how they handle data. They make data harvesting part of their sales pitch. GTL/ViaPath, the second-largest provider of e-messaging services, advertises to correctional facilities by bragging about its “Data IQ” product, a data-mining technology that the company claims “was designed to handle large volumes of data coming from multiple, disparate sources” to “enable correctional facilities to easily review and analyze the networks, relationships, and connections associated with their inmate population.” The company makes clear it is pumping e-messaging data into its analytics system and using it as yet another surveillance tool that targets people based on nothing more than their contact with an incarcerated person.

While incarcerated people may not have the same privacy rights as those outside the prison walls, they — and the people they exchange messages with — still have a right to know how their data will be handled, and they are entitled to more robust privacy protections than they currently receive. There should be clear guidelines, procedures, disclosure requirements, and protections whenever e-messaging data is accessed by anyone other than an employee of the correctional facility that issued the governing contract.

Making electronic messaging work for incarcerated people, their families, and even prisons

E-messaging can help incarcerated people and their loved ones maintain stronger connections, despite long distances and metal bars. Thus far, though, companies have prioritized profits over functionality.

The service doesn’t have to be expensive, cumbersome, and lacking essential features [[link removed]]. There are five things correctional administrators, legislators, and regulators can do to realize its full benefits:

Make the service free

Electronic messaging has the potential to benefit correctional facilities, incarcerated people, and family members. But to be a win-win-win, the service must be free for end-users. And because correctional facilities stand to reap cost-savings from e-messaging, they should foot the bill.

Traditional physical mail should always remain an accessible option for people to send and receive messages, cards, and other correspondence to and from loved ones on the outside. Unfortunately, citing the costs associated with mail processing, some prisons have waged a virtual war on physical mail by scanning or photocopying incoming mail [[link removed]] and distributing digital images or reprints to the recipient (while destroying the original handwritten card or letter). This eliminates the essential human connection of cards and letters and dramatically increases the time between when someone on the outside sends a letter and when their incarcerated loved one receives it. Predictably and for good reason, this has been met with fierce resistance from people on both sides of prison walls.

E-messaging offers a better path that protects physical mail, promotes communication between incarcerated people and the outside world, and addresses the concerns of prison officials about the challenges of processing mail without using harmful scanning technology. By making the service free, incarcerated people and their families will be more likely to use e-messaging for their daily written communications while preserving physical mail as an option. This will likely reduce the amount of mail a facility has to process and deliver considerable cost savings.

Provide better and more useful features

Traditional email is far from perfect, but it offers a model for what e-messaging can be. Prisons should demand that e-messaging providers add features that:

Allow users on the inside to send traditional emails to anyone with an email address. Support documents, government forms, copies of news stories, and other attachments. Highly sensitive computer systems (like those run by courts and tax agencies) have figured out safe ways to do this. E-messaging companies should get on board and allow users to create, attach, send, and receive simple files like PDFs, website screenshots, and word-processing documents. Eliminate character limits; they’re restrictive, arbitrary, and technologically unnecessary. Give users clear ownership over the content of their messages and a simple and free way to export their data to another program, like Outlook. Allow non-English characters

Eliminate site commissions

Even if a prison system doesn’t offer e-messaging for free, at the very least, it should eliminate site commissions on the service. This will lower the per-message cost to users and likely produce savings for the prison. Regardless of whether facilities receive commission revenue from other communications services, they should categorically forgo commissions on electronic messaging.

Allow competition

Any correctional facility that deploys e-messaging on personal tablets has the technical capability to allow competing providers to add their apps to the tablet. If people have a choice between two or more providers, market forces are likely to drive prices down and improve functionality. The tablet vendor will undoubtedly complain, but facilities have the upper hand. Allowing other apps onto tablets should become a standard requirement of procurement requests.

Define users’ privacy rights

At a minimum, all correctional facilities should require that e-messaging providers’ privacy policies tell users information is stored, how long it is stored, how it is protected, who has access to it, and what happens if that data is inappropriately breached.

***

For more information, including state-by-state pricing data, an explanation of seven ways e-messaging is worse than email, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this report on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023 [[link removed]]

The various government agencies involved in the criminal legal system collect a lot of data, but very little is designed to help policymakers or the public understand what’s going on.

In this new edition of our flagship report [[link removed]], we pull together the data from disparate pieces of the criminal legal system to show how many people are incarcerated, what type of facility they are in, and why. We also bust 9 common myths about mass incarceration and explain the impact of COVID on prison and jail populations.

State of Phone Justice 2022: The problem, the progress, and what's next [[link removed]]

At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, why are incarcerated people and their families charged so much?

In this report from late last year [[link removed]] we look at data from all 50 states and more than 3,000 jails to understand how much families pay and how companies are finding new ways to price-gouge them through an expanding array of non-phone products.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for March 28, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

SMH: The rapid & unregulated growth of e- messaging in prisons [[link removed]] A technology that, until recently, was new in prisons and jails has exploded in popularity in recent years. Our review found that, despite its potential to keep incarcerated people and their families connected, e-messaging has quickly become just another way for companies to profit at their expense. [[link removed]]

by Mike Wessler

Over the last twenty years, advocates and regulators have successfully lowered the prices of prison and jail phone rates. While these victories garnered headlines and attention, the companies behind these services quietly regrouped and refocused their efforts. Seeking different ways to protect their profits, they entered less-regulated industries and offered new products to people behind bars. One new service in particular — text-based electronic messaging or “e-messaging” — has experienced explosive and unregulated growth. As a result, rather than living up to its potential as a way to maintain connections between people in prison and the outside world — something that benefits all of us [[link removed]] — high costs and shoddy technology have made e-messaging little more than the latest way these companies drain money from incarcerated people and their loved ones.

In 2016, we released a groundbreaking report [[link removed]] that took a first look at e-messaging, sometimes — but incorrectly — called “email.” At that time, the technology was experimental, untested, and viewed skeptically by many correctional administrators. Since then, though, it has become common inside prison walls.

To better understand this explosive growth in e-messaging, we examined all 50 state prison systems, as well as the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), to see how common this technology has become, how much it costs, and what, if anything, is being done to protect incarcerated people and their families from exploitation. We found an industry that is in flux, expanding quickly, and has yet to face the legislative and regulatory oversight it desperately needs.

The explosive growth of e-messaging in prisons

When we looked at e-messaging in 2016, the technology was relatively new, having broached the walls of only a handful of prisons and jails nationwide. Today, we’ve found that at least 43 state prison systems and the BOP offer some electronic messaging option.

Like most prison communications services, e-messaging is dominated by just a few corporations. One company has established a particularly firm grasp on this market: Securus, under its “JPay” brand. The company serves half of the prison systems that offer e-messaging, holding contracts in 22 states. The other dominant company in the space, Global Tel*Link (GTL), which recently rebranded to ViaPath, provides e-messaging for fifteen prison systems. These two companies dominate more than 81% of the prison e-messaging market. The third most common e-messaging provider is CorrLinks, developed and owned by Advanced Technologies Group, LLC (part of the private-equity-owned Keefe Group family of correctional vendors).

Tablets are the new “it thing.”

In the early days of the technology, incarcerated users often had to wait in line to use a shared computer (or “kiosk”) to read or send electronic messages. Now messaging is commonly part of a computer tablet [[link removed]] package, where each incarcerated user is either assigned their own tablet or checks one out for a set period of time. In terms of usability, this is good news (no one should have to write a letter home with a line of impatient people waiting behind them). But serious questions about the economics of tablet programs remain. These tablets are often touted as “free” but, in reality, are rife with hidden costs [[link removed]]. The Covid-19 pandemic has been an economic boon [[link removed]] for the companies that operate these programs, yet as tablets become more common, the companies providing them continue their relentless push to monetize [[link removed]] every aspect of incarcerated peoples’ communications [[link removed]], reading [[link removed]], listening to music [[link removed]], and formal education [[link removed]]. There are also grave privacy concerns when one company controls all communications channels to which incarcerated people have access.

Prices are down…sort of

The per-message price of sending an electronic message appears to have inched down since 2016. Unfortunately, some companies have found new ways to maximize their profits while hiding the actual cost of the service.

In our 2016 survey, the typical cost of sending a message was roughly the cost of a first-class postage stamp (at the time, a stamp was 49¢). We’ve previously explained [[link removed].] that the price of a stamp has nothing to do with the cost of providing electronic messaging services, so there is little justification for tying the two products together. The costs to the company when an incarcerated person sends a message should be nearly nothing considering it requires no paper or staff labor, and the many other ways the companies already make up the cost of providing their so-called “free” tablets [[link removed]]. Fortunately, linking the price of an e-message to the cost of a stamp has become less prevalent.

Today, our rate survey [[link removed]] found the cost to send an e-message ranges from being free in Connecticut to a high of 50¢ in Alaska and Arkansas, with prices most often between 27¢ to 30¢. This wide range suggests that prices are not tied to the actual costs companies incur to transmit a message but rather set at the point that will maximize profits.

For detailed pricing information for each state, see this report's appendix on our website [[link removed]].

Bulk-pricing schemes are common, confusing, and harm the poorest people

A frequent tactic used by companies is “bulk-pricing.” About half of the states that offer electronic messaging include bulk-pricing schemes [[link removed]], where customers pay a higher cost unless they prepay for larger blocks of messages. This method has two primary problems: First, it often results in people buying large packages of messages they may never use, ultimately wasting their money. Second, it charges the poorest people in prison — people who can only afford a small number of messages at a given time — the most money.

For example, in Alaska, if someone has the money to purchase 40 messages at once, they’ll pay $14 or 35¢ per message. However, if they can only afford one message at a time, they’ll pay 50¢ per message — a roughly 43% price increase.

Bulk-pricing schemes are effectively a fee paid only by the poorest people.

Bulk pricing structures like these are common outside of prison and often are an effective way for businesses to sell their products and for consumers to get discounts. But, inside the prison walls, where most people are already economically disadvantaged [[link removed]] and have little means to earn money [[link removed]], bulk-pricing schemes are effectively a fee paid only by the poorest people.

These schemes invite the question: Why don’t these companies charge the lowest price possible for every message?

The hidden costs of per-minute pricing

Per-messaging pricing only tells a part of the story, however. Some states use a more complex pricing structure that can dramatically increase the amount people pay, and companies earn from a single message. In these states, people sending a message to a loved one in prison are charged a simple per-message price. However, people in prisons are charged per minute to use the tablet computer to read and respond to messages. For example, in Delaware, GTL/ViaPath charges people on the outside 25¢ to send a message. However, it costs 5¢ center per minute for incarcerated people to read or respond to the message.

This pricing structure is troubling for many reasons. First, research has shown [[link removed]] that people in prison often have lower literacy levels, meaning it likely takes them longer to send and read e-messages. Per-minute pricing acts as a literacy tax, making it far more expensive for people who struggle to read and respond to messages. This pricing structure also makes it nearly impossible to assess what incarcerated people are charged for e-messaging and means companies are profiting twice off of the same message — once when someone sends a message to their loved one in prison and again when that loved one reads it. It is hard to determine how many prisons use this model, but it seems to be most frequently used in prisons that contract with GTL/ViaPath. This complex pricing structure is one of the many problems with “ bundled contracts [[link removed]],” which give one company control over multiple services in a prison, allowing them to evade oversight and develop new hidden ways to sap money from incarcerated people.

Waiving commissions, unsurprisingly, leads to lower prices

Through years of abusive practices by prison and jail phone companies, many correctional systems developed an unhealthy reliance on “site commissions,” or kickbacks, to make money off incarcerated people and their families. These commissions have, unfortunately, spilled over into other services, like electronic messaging.

It may be distasteful, but it is not surprising that companies like Securus and GTL seek to profit off of incarcerated people and their families — like it or not, it is the type of behavior we’ve come to expect from corporations and why strong regulatory oversight is needed in this space. Our expectations of government are different, however. Governments should be in the business of serving people, not profiting off of their suffering. This is why these kickbacks are such a problem. They unnecessarily drain money from incarcerated people and their families without providing any added benefit.

Any price that includes kickbacks for the government is higher than it needs to be.Unsurprisingly, among states that charge incarcerated people to send e-messages, prison systems that say they do not receive site-commission revenue have some of the lowest prices. For example, the Illinois Department of Corrections only charges 15¢ per message, and the New York Department of Corrections & Community Supervision charges 15¢-20¢, depending on volume.

As state and federal officials debate how much people in prisons and their loved ones are charged for sending e-messages, they should remember that any price that includes kickbacks for the government is higher than it needs to be.

Little is known about how companies use the data they collect

The quantity and sensitivity of information captured in e-messaging systems — from people on both sides of the prison walls — is staggering. They hold two main types of data, personal information — such as names, addresses, and payment card information — and the contents of the messages. However, the technology providers have done little to explain how users’ data is stored, protected, and used. For example, JPay states in its privacy policy [[link removed]] that users’ data may be shared “with law enforcement personnel and/or correctional facilities and certain third parties for use in connection with and in support of law enforcement activities.” This vague language gives wide latitude to the companies but few answers to users. By using the product, customers (whether they’re the person in prison or the person on the outside) are handing over their data without knowing who can see it, how they can use it, or what protections are in place to ensure it isn’t improperly accessed.

Other providers, though, are not simply vague about how they handle data. They make data harvesting part of their sales pitch. GTL/ViaPath, the second-largest provider of e-messaging services, advertises to correctional facilities by bragging about its “Data IQ” product, a data-mining technology that the company claims “was designed to handle large volumes of data coming from multiple, disparate sources” to “enable correctional facilities to easily review and analyze the networks, relationships, and connections associated with their inmate population.” The company makes clear it is pumping e-messaging data into its analytics system and using it as yet another surveillance tool that targets people based on nothing more than their contact with an incarcerated person.

While incarcerated people may not have the same privacy rights as those outside the prison walls, they — and the people they exchange messages with — still have a right to know how their data will be handled, and they are entitled to more robust privacy protections than they currently receive. There should be clear guidelines, procedures, disclosure requirements, and protections whenever e-messaging data is accessed by anyone other than an employee of the correctional facility that issued the governing contract.

Making electronic messaging work for incarcerated people, their families, and even prisons

E-messaging can help incarcerated people and their loved ones maintain stronger connections, despite long distances and metal bars. Thus far, though, companies have prioritized profits over functionality.

The service doesn’t have to be expensive, cumbersome, and lacking essential features [[link removed]]. There are five things correctional administrators, legislators, and regulators can do to realize its full benefits:

Make the service free

Electronic messaging has the potential to benefit correctional facilities, incarcerated people, and family members. But to be a win-win-win, the service must be free for end-users. And because correctional facilities stand to reap cost-savings from e-messaging, they should foot the bill.

Traditional physical mail should always remain an accessible option for people to send and receive messages, cards, and other correspondence to and from loved ones on the outside. Unfortunately, citing the costs associated with mail processing, some prisons have waged a virtual war on physical mail by scanning or photocopying incoming mail [[link removed]] and distributing digital images or reprints to the recipient (while destroying the original handwritten card or letter). This eliminates the essential human connection of cards and letters and dramatically increases the time between when someone on the outside sends a letter and when their incarcerated loved one receives it. Predictably and for good reason, this has been met with fierce resistance from people on both sides of prison walls.

E-messaging offers a better path that protects physical mail, promotes communication between incarcerated people and the outside world, and addresses the concerns of prison officials about the challenges of processing mail without using harmful scanning technology. By making the service free, incarcerated people and their families will be more likely to use e-messaging for their daily written communications while preserving physical mail as an option. This will likely reduce the amount of mail a facility has to process and deliver considerable cost savings.

Provide better and more useful features

Traditional email is far from perfect, but it offers a model for what e-messaging can be. Prisons should demand that e-messaging providers add features that:

Allow users on the inside to send traditional emails to anyone with an email address. Support documents, government forms, copies of news stories, and other attachments. Highly sensitive computer systems (like those run by courts and tax agencies) have figured out safe ways to do this. E-messaging companies should get on board and allow users to create, attach, send, and receive simple files like PDFs, website screenshots, and word-processing documents. Eliminate character limits; they’re restrictive, arbitrary, and technologically unnecessary. Give users clear ownership over the content of their messages and a simple and free way to export their data to another program, like Outlook. Allow non-English characters

Eliminate site commissions

Even if a prison system doesn’t offer e-messaging for free, at the very least, it should eliminate site commissions on the service. This will lower the per-message cost to users and likely produce savings for the prison. Regardless of whether facilities receive commission revenue from other communications services, they should categorically forgo commissions on electronic messaging.

Allow competition

Any correctional facility that deploys e-messaging on personal tablets has the technical capability to allow competing providers to add their apps to the tablet. If people have a choice between two or more providers, market forces are likely to drive prices down and improve functionality. The tablet vendor will undoubtedly complain, but facilities have the upper hand. Allowing other apps onto tablets should become a standard requirement of procurement requests.

Define users’ privacy rights

At a minimum, all correctional facilities should require that e-messaging providers’ privacy policies tell users information is stored, how long it is stored, how it is protected, who has access to it, and what happens if that data is inappropriately breached.

***

For more information, including state-by-state pricing data, an explanation of seven ways e-messaging is worse than email, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this report on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023 [[link removed]]

The various government agencies involved in the criminal legal system collect a lot of data, but very little is designed to help policymakers or the public understand what’s going on.

In this new edition of our flagship report [[link removed]], we pull together the data from disparate pieces of the criminal legal system to show how many people are incarcerated, what type of facility they are in, and why. We also bust 9 common myths about mass incarceration and explain the impact of COVID on prison and jail populations.

State of Phone Justice 2022: The problem, the progress, and what's next [[link removed]]

At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, why are incarcerated people and their families charged so much?

In this report from late last year [[link removed]] we look at data from all 50 states and more than 3,000 jails to understand how much families pay and how companies are finding new ways to price-gouge them through an expanding array of non-phone products.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor