March 3, 2023

Permission to republish original opeds and cartoons granted.

As 10-year, 2-year inversion reaches new lows in cycle, peak employment persists as Fed hopes inflation will come down all by itself

By Robert Romano

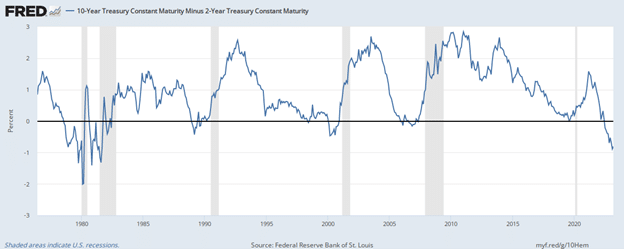

The spread between 10-year treasuries and 2-year treasuries, often a reliable recession predictor, has been inverted since June 13, following another brief inversion on March 31 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the worsening global supply crisis that has led to crushing consumer inflation the past year, which still remains elevated at 6.4 percent over twelve months after peaking at 9.1 percent in June 2022.

Usually, a recession will occur on average 14 months after the inversion, with a range of 7 to 18 months. The exception to the rule so far was 1998, when there was a very brief inversion, but a recession did not intervene before it inverted again in 2000, predicting the 2001 recession. So, there are head fakes on recession indicators like the 10-year, 2-year, but they are not terribly common.

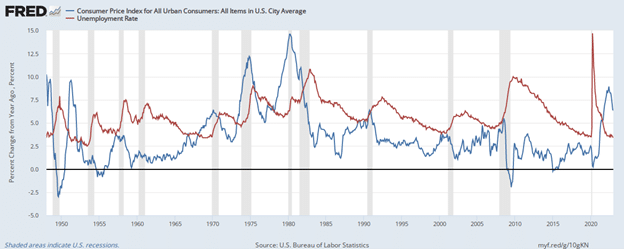

In the meantime, unemployment remains near historic lows of 3.4 percent, and job openings near record highs at 11 million — although it is still off its March 2022 high of 11.8 million — indicating peak employment, a condition which usually doesn’t last forever before demand collapses and labor markets contract.

Inflation and rising interest rates—we have both right now—are often the catalyst for those pendulum swings, as consumers max out on their credit and then stop spending to service that debt. The annual growth of consumer credit appears to have peaked at 8.1 percent in Oct. 2022, and has flattened and is slightly down to 7.8 percent annualized in Dec. 2022.

In every single recession in modern history, peak inflation and employment was followed by a dipping of the inflation rate and an increase in the unemployment rate, sometimes by a lot, and sometimes by a bit. On average, the process appears to take about 15 months, but the range is as few as 3 months to as many as 39 months, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

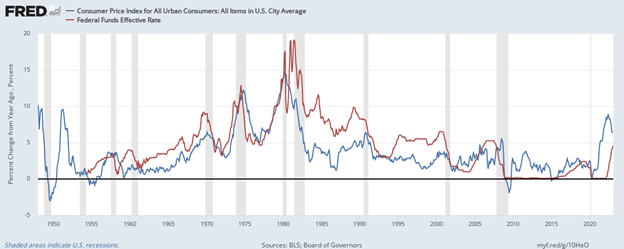

The Federal Reserve for its part in its Feb. 1 meeting of the Board of Governors kept hiking the Federal Funds Rate to 4.5 to 4.75 percent as the Fed said it “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range” could be necessary going forward.

According to the central bank’s statement, “the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 4-1/2 to 4-3/4 percent. The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

In recent history, since 2000, the Fed has tended to keep interest rates below that of the consumer inflation rate — not dissimilar to the 1970s — only hiking interest rates until they get above the consumer inflation rate, whereas from 1980 to 2000, it tended to keep interest rates above inflation to tame the Great Inflation of the 1970s and 1980s.

But there is certainly still a lot of money to sop up from the more than $6 trillion was spent, borrowed and printed in response to the economic lockdowns, production halts and the temporary spike in unemployment, where 25 million Americans lost their jobs during Covid.

As a result the M2 money supply increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, leading to the inflation spike, where consumer inflation reached 9.1 percent in June 2022. In fact, by the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022—further worsening global supply issues—consumer inflation was already north of 7.5 percent. The inflation was going to happen anyway.

The question for the Fed is whether it wants the inflation to continue. Usually, recessions have been the thing to bring it under control, but the central bank seems reticent to bring the Federal Funds Rate above that of consumer inflation. That could be political, not wishing to trigger a recession before President Joe Biden runs for reelection in 2024. Or maybe they just bought the so-called "soft landing" happy talk.

Ironically, if the Fed had just ripped off the band-aid last year, perhaps a recession would have already been triggered, but inflation would have receded and labor markets might have already bottomed. Instead, kicking the can down the road without the cooling floods of the labor market downturn might be putting said recession squarely into 2024. Whoops!

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

Video: Will The Supreme Court BREAK The Internet?

To view online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATXf-5FeOyA