| From | Portside Culture <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The Responsibility of Watching |

| Date | February 1, 2023 1:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[The Responsibility of Watching the video of Memphis police

beating Tyre Nichols challenges public complacency — and complicity.

What are our duties as citizens and as human beings? ]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

THE RESPONSIBILITY OF WATCHING

[[link removed]]

A.O. Scott

January 28, 2023

The New York Times

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ The Responsibility of Watching the video of Memphis police beating

Tyre Nichols challenges public complacency — and complicity. What

are our duties as citizens and as human beings? _

,

Do you have a civic duty to watch, or a moral obligation not to?

Some version of that question has confronted us since the body- and

pole-camera footage of Memphis police officers beating Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]] was

released on Friday evening. The argument isn’t necessarily about

whether the Police Department should have posted the roughly hourlong,

four-part, lightly redacted video online for everyone to see.

The legal and political reasons for doing so, at the urging of Mr.

Nichols’s family, seem obvious and cogent. Too often, the worst

abuses of power are allowed to fester in secrecy, shrouded in lies,

bureaucratic language and partial information. Raw video offers

clarity, transparency and perhaps accountability — a chance for

citizens to understand the unvarnished truth about what happened on

the night of Jan. 7.

That is the hope, in any case: that concerned Americans will become

witnesses after the fact, our senses shocked and our consciences

awakened by the sight of uniformed officers repeatedly kicking and

punching Mr. Nichols, who would die from his injuries three days

later. “I expect you to feel what the Nichols family feels,”

Cerelyn Davis, the Memphis police chief, said in anticipation of the

video’s impact. Her appeal to common humanity expressed faith in the

power of even the most horrific images to foster empathy and community

— and faith in the human capacity to experience outrage and

compassion when shown such images.

That faith provides a strong argument for the importance of looking.

To turn away in circumstances like this would not merely be to succumb

to a loss of nerve, but to risk a loss of heart. In insisting that the

world see what had been done to her son, RowVaughn Wells, Mr.

Nichols’s mother, recalled Mamie Till-Mobley

[[link removed]],

who in 1955 placed the disfigured body of her murdered son, Emmett, in

an open coffin so that the viciousness of the racists who killed him

could not be denied.

A delicate ethical line separates witness — an active, morally

engaged state of attention — from the more passive, less demanding

condition of spectatorship. The spectacle of violence has a way of

turning even sensitive souls into gawkers and voyeurs. Violence, very

much including the actions of the police, is a fixture of popular

culture, and has been since long before the invention of video. For

much of human history, public executions have been a form of

entertainment. The history of lynching in the United States is in part

a history of public spectacle, in which the mutilation and murder of

Black men brought out white crowds to stare, cheer and take

photographs.

I’m not saying that looking at the video of Mr. Nichols’s beating

is equivalent to joining in one of those crowds, but rather that Black

suffering in America has often been either relegated to invisibility

or subjected to exploitation and commodification. That is the dilemma

that Ms. Wells and others in her position have faced, even as she

challenges the public to acknowledge her son’s full humanity.

We don’t automatically recoil from violence. We can just as easily

respond with indifference, morbid fascination — or worse. Images are

powerful, but not powerful enough to compensate for a society’s

failures of decency or judgment, or to overcome its commitment to

denying truths that should be self-evident. Mr. Nichols’s case

can’t help but recall the police beating of Rodney King

[[link removed]] in

Los Angeles in 1991, captured on video by a neighbor. The officers in

that case were acquitted, and unrest swept the city.

On Friday, not long before the Memphis videos were posted, a police

body-cam clip was released showing part of the Oct. 28 assault

[[link removed]] on

former Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband, Paul, at his home in San

Francisco. That attack, carried out by an apparent right-wing

extremist, had been the subject of grotesque jokes and lurid, baseless

speculations from some of his wife’s political enemies. While the

video seems to refute all such claims, it is unlikely to stem the tide

of conspiracism and fantasy in some right-wing precincts. The assault

on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, also involved extremists hunting

for Ms. Pelosi, and in spite of abundant documentation has been

treated by partisans as a tangle of mystery, indeterminacy and

through-the-looking-glass distortion

Video may not lie, but people do. The fact that even the plainest

images are open to interpretation, manipulation and

mischaracterization places an ethical burden on the viewer. The cost

of looking is thinking about what we see. Video is a tool, not a

shortcut or a solution. Three decades after the Rodney King beating,

Derek Chauvin was convicted of murdering George Floyd, and a

bystander’s video of his killing galvanized a global protest

movement. What we do with the images is what matters.

What do we do with these images that come from official sources, and

that exist partly because of the impulse to keep a closer eye on law

enforcement? In the Memphis videos what is perhaps most heartbreaking,

and most chilling, is the casual indifference of the officers to Mr.

Nichols’s anguish — and to the cameras that recorded it.

In the pole-camera video, which is the longest of the four segments

and has no sound, you see him crumpled against the side of a patrol

car and collapsing onto the ground as his assailants and an

ever-increasing number of their colleagues mill around, mostly

ignoring him. Someone lights a cigarette. Someone fiddles with a

clipboard. Because of the silence of the soundtrack and the immobility

of the camera, time seems to slow down, and action mutates into

abstraction. A human catastrophe is playing out under a ruthlessly

impersonal eye looking down from above.

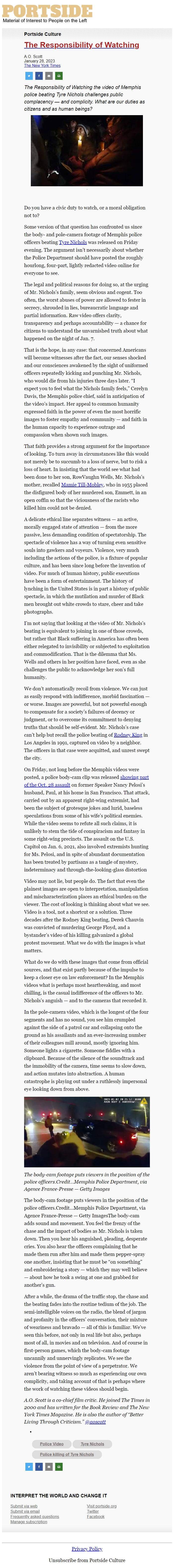

[An officer’s hands hold a stun gun pointed at a figure running in

the distance. They’re on a street with a car stopped,

driver’s-side door open and taillights on. ]

_The body-cam footage puts viewers in the position of the police

officers.Credit...Memphis Police Department, via Agence France-Presse

— Getty Images_

The body-cam footage puts viewers in the position of the police

officers.Credit...Memphis Police Department, via Agence France-Presse

— Getty ImagesThe body-cam adds sound and movement. You feel the

frenzy of the chase and the impact of bodies as Mr. Nichols is taken

down. Then you hear his anguished, pleading, desperate cries. You also

hear the officers complaining that he made them run after him and made

them pepper-spray one another, insisting that he must be “on

something” and embroidering a story — which they may well believe

— about how he took a swing at one and grabbed for another’s gun.

After a while, the drama of the traffic stop, the chase and the

beating fades into the routine tedium of the job. The

semi-intelligible voices on the radio, the blend of jargon and

profanity in the officers’ conversation, their mixture of weariness

and bravado — all of this is familiar. We’ve seen this before, not

only in real life but also, perhaps most of all, in movies and on

television. And of course in first-person games, which the body-cam

footage uncannily and unnervingly replicates. We see the violence from

the point of view of a perpetrator. We aren’t bearing witness so

much as experiencing our own complicity, and taking account of that is

perhaps where the work of watching these videos should begin.

_A.O. Scott is a co-chief film critic. He joined The Times in 2000 and

has written for the Book Review and The New York Times Magazine. He is

also the author of “Better Living Through Criticism.” @aoscott

[[link removed]]_

*

* Police Video

[[link removed]]

* Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]]

* Police killing of Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit portside.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

beating Tyre Nichols challenges public complacency — and complicity.

What are our duties as citizens and as human beings? ]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

THE RESPONSIBILITY OF WATCHING

[[link removed]]

A.O. Scott

January 28, 2023

The New York Times

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ The Responsibility of Watching the video of Memphis police beating

Tyre Nichols challenges public complacency — and complicity. What

are our duties as citizens and as human beings? _

,

Do you have a civic duty to watch, or a moral obligation not to?

Some version of that question has confronted us since the body- and

pole-camera footage of Memphis police officers beating Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]] was

released on Friday evening. The argument isn’t necessarily about

whether the Police Department should have posted the roughly hourlong,

four-part, lightly redacted video online for everyone to see.

The legal and political reasons for doing so, at the urging of Mr.

Nichols’s family, seem obvious and cogent. Too often, the worst

abuses of power are allowed to fester in secrecy, shrouded in lies,

bureaucratic language and partial information. Raw video offers

clarity, transparency and perhaps accountability — a chance for

citizens to understand the unvarnished truth about what happened on

the night of Jan. 7.

That is the hope, in any case: that concerned Americans will become

witnesses after the fact, our senses shocked and our consciences

awakened by the sight of uniformed officers repeatedly kicking and

punching Mr. Nichols, who would die from his injuries three days

later. “I expect you to feel what the Nichols family feels,”

Cerelyn Davis, the Memphis police chief, said in anticipation of the

video’s impact. Her appeal to common humanity expressed faith in the

power of even the most horrific images to foster empathy and community

— and faith in the human capacity to experience outrage and

compassion when shown such images.

That faith provides a strong argument for the importance of looking.

To turn away in circumstances like this would not merely be to succumb

to a loss of nerve, but to risk a loss of heart. In insisting that the

world see what had been done to her son, RowVaughn Wells, Mr.

Nichols’s mother, recalled Mamie Till-Mobley

[[link removed]],

who in 1955 placed the disfigured body of her murdered son, Emmett, in

an open coffin so that the viciousness of the racists who killed him

could not be denied.

A delicate ethical line separates witness — an active, morally

engaged state of attention — from the more passive, less demanding

condition of spectatorship. The spectacle of violence has a way of

turning even sensitive souls into gawkers and voyeurs. Violence, very

much including the actions of the police, is a fixture of popular

culture, and has been since long before the invention of video. For

much of human history, public executions have been a form of

entertainment. The history of lynching in the United States is in part

a history of public spectacle, in which the mutilation and murder of

Black men brought out white crowds to stare, cheer and take

photographs.

I’m not saying that looking at the video of Mr. Nichols’s beating

is equivalent to joining in one of those crowds, but rather that Black

suffering in America has often been either relegated to invisibility

or subjected to exploitation and commodification. That is the dilemma

that Ms. Wells and others in her position have faced, even as she

challenges the public to acknowledge her son’s full humanity.

We don’t automatically recoil from violence. We can just as easily

respond with indifference, morbid fascination — or worse. Images are

powerful, but not powerful enough to compensate for a society’s

failures of decency or judgment, or to overcome its commitment to

denying truths that should be self-evident. Mr. Nichols’s case

can’t help but recall the police beating of Rodney King

[[link removed]] in

Los Angeles in 1991, captured on video by a neighbor. The officers in

that case were acquitted, and unrest swept the city.

On Friday, not long before the Memphis videos were posted, a police

body-cam clip was released showing part of the Oct. 28 assault

[[link removed]] on

former Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband, Paul, at his home in San

Francisco. That attack, carried out by an apparent right-wing

extremist, had been the subject of grotesque jokes and lurid, baseless

speculations from some of his wife’s political enemies. While the

video seems to refute all such claims, it is unlikely to stem the tide

of conspiracism and fantasy in some right-wing precincts. The assault

on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, also involved extremists hunting

for Ms. Pelosi, and in spite of abundant documentation has been

treated by partisans as a tangle of mystery, indeterminacy and

through-the-looking-glass distortion

Video may not lie, but people do. The fact that even the plainest

images are open to interpretation, manipulation and

mischaracterization places an ethical burden on the viewer. The cost

of looking is thinking about what we see. Video is a tool, not a

shortcut or a solution. Three decades after the Rodney King beating,

Derek Chauvin was convicted of murdering George Floyd, and a

bystander’s video of his killing galvanized a global protest

movement. What we do with the images is what matters.

What do we do with these images that come from official sources, and

that exist partly because of the impulse to keep a closer eye on law

enforcement? In the Memphis videos what is perhaps most heartbreaking,

and most chilling, is the casual indifference of the officers to Mr.

Nichols’s anguish — and to the cameras that recorded it.

In the pole-camera video, which is the longest of the four segments

and has no sound, you see him crumpled against the side of a patrol

car and collapsing onto the ground as his assailants and an

ever-increasing number of their colleagues mill around, mostly

ignoring him. Someone lights a cigarette. Someone fiddles with a

clipboard. Because of the silence of the soundtrack and the immobility

of the camera, time seems to slow down, and action mutates into

abstraction. A human catastrophe is playing out under a ruthlessly

impersonal eye looking down from above.

[An officer’s hands hold a stun gun pointed at a figure running in

the distance. They’re on a street with a car stopped,

driver’s-side door open and taillights on. ]

_The body-cam footage puts viewers in the position of the police

officers.Credit...Memphis Police Department, via Agence France-Presse

— Getty Images_

The body-cam footage puts viewers in the position of the police

officers.Credit...Memphis Police Department, via Agence France-Presse

— Getty ImagesThe body-cam adds sound and movement. You feel the

frenzy of the chase and the impact of bodies as Mr. Nichols is taken

down. Then you hear his anguished, pleading, desperate cries. You also

hear the officers complaining that he made them run after him and made

them pepper-spray one another, insisting that he must be “on

something” and embroidering a story — which they may well believe

— about how he took a swing at one and grabbed for another’s gun.

After a while, the drama of the traffic stop, the chase and the

beating fades into the routine tedium of the job. The

semi-intelligible voices on the radio, the blend of jargon and

profanity in the officers’ conversation, their mixture of weariness

and bravado — all of this is familiar. We’ve seen this before, not

only in real life but also, perhaps most of all, in movies and on

television. And of course in first-person games, which the body-cam

footage uncannily and unnervingly replicates. We see the violence from

the point of view of a perpetrator. We aren’t bearing witness so

much as experiencing our own complicity, and taking account of that is

perhaps where the work of watching these videos should begin.

_A.O. Scott is a co-chief film critic. He joined The Times in 2000 and

has written for the Book Review and The New York Times Magazine. He is

also the author of “Better Living Through Criticism.” @aoscott

[[link removed]]_

*

* Police Video

[[link removed]]

* Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]]

* Police killing of Tyre Nichols

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit portside.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV