|

I began the new year 2022 as a convicted felon. I was cut off by the judge mid-sentence in my opening statement in North Carolina, in a trial regarding the rescue of baby Rain from a meat farm in Transylvania County. And things went downhill from there. The judge prohibited me from discussing the cruelty we saw at the farm; barred our expert from testifying about the emergency medical care we provided to keep him alive; and even threatened to remove me from the courtroom (and presumably send me to jail) for repeatedly attempting to tell the true story of what happened in Transylvania County. The government had a new weapon — gagging us in court — in what The Intercept described as “the war against those who would put the value of life ahead of property.”

It was not the best start, for me or the animal rights movement, in our efforts to make the world a kinder place for animals.

Very few would have predicted, therefore, that 2022 turned out the way it has: as a historically successful year for animal rights.

The first sign was the introduction of AB2764 in the California Assembly. The bill, which would have barred the new construction of factory farms and slaughterhouses, seemed somewhere between joke and pipe dream when activists at DxE and Compassionate Bay began lobbying for it in early 2022. When we received the email that it was going to be introduced, in the middle of the trial of Matt Johnson, people were smiling and literally jumping up and down. Perhaps North Carolina and Iowa and Utah would prosecute those who expose factory farms, but California (it seemed) would take a stand against them, and for the advocates risking so much to challenge them. While the bill ultimately was killed before it even came to a vote, the mere fact that it was introduced was a major victory.

The second sign that something was changing was the increasing inclusion of factory farms in the discussion of climate justice. An August 2022 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences comprehensively assessed the environmental impacts of the most commonly-eaten foods across the globe, over 57,000 in total. It was a gargantuan task, but led to a startling conclusion: switching to a plant-based diet could reduce the environmental damage caused by our food system by as much as 90%! Coming in the wake of other recent studies in top scientific journals — showing that it would be impossible to limit global warming to 1.5°C without shifting away from the consumption of meat, and that a switch to plant-based eating is “the single biggest way” that ordinary people can reduce their environmental footprint — one could argue that 2022 was the year that the environmental threats posed by factory farming finally broke into the mainstream. It’s one of the reasons that even large NGOs that have historically been terrified by talking about meat — out of the fear of losing their membership base — have finally started embracing plant-based eating.

But perhaps the most important sign of progress for animals was our victory in Utah. I’ve already written extensively, both on this blog and in The New York Times (among other places), about the significance of our victory for the right to rescue. The Smithfield trial establishes what is the most promising strategy for revolutionary social change for animals that I’ve witnessed in my 20+ years of activism. (If you want to understand more of how this strategy can be deployed, join the Smithfield Trial Summit that will be hosted by the University of Denver College of Law from Jan 13-15. I’ll be there, and so will many of the jurors who made the historic decision!)

What’s perhaps most surprising about these signs of progress, however, is that 2022 also taught us that the world is in bad shape. Very, very bad shape. Here are some of those cautionary lessons.

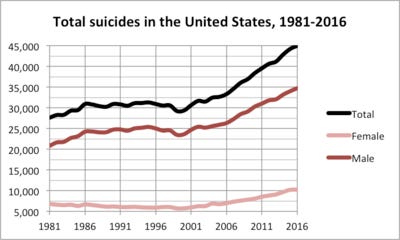

The first is that our mental health is facing historic problems. Anxiety and depression have shot up in recent years, with a March 2022 report by the World Health Organization suggesting a worldwide increase in these mental disorders of 25%. The problem is especially acute among young people, with the American Psychological Association declaring a “crisis” in youth mental health. Suicide, which surprisingly decreased slightly during COVID-19, shot up again in 2021 to near historic highs. This continues a long-term trend of more and more people killing themselves in what is, in theory, the most prosperous nation in human history.

Finally, the addiction crisis became a literal plague on our nation in the last year, with over 100,000 people dying from overdose deaths for the first time in history. Far more people are suffering, even if they have not overdosed or committed suicide.

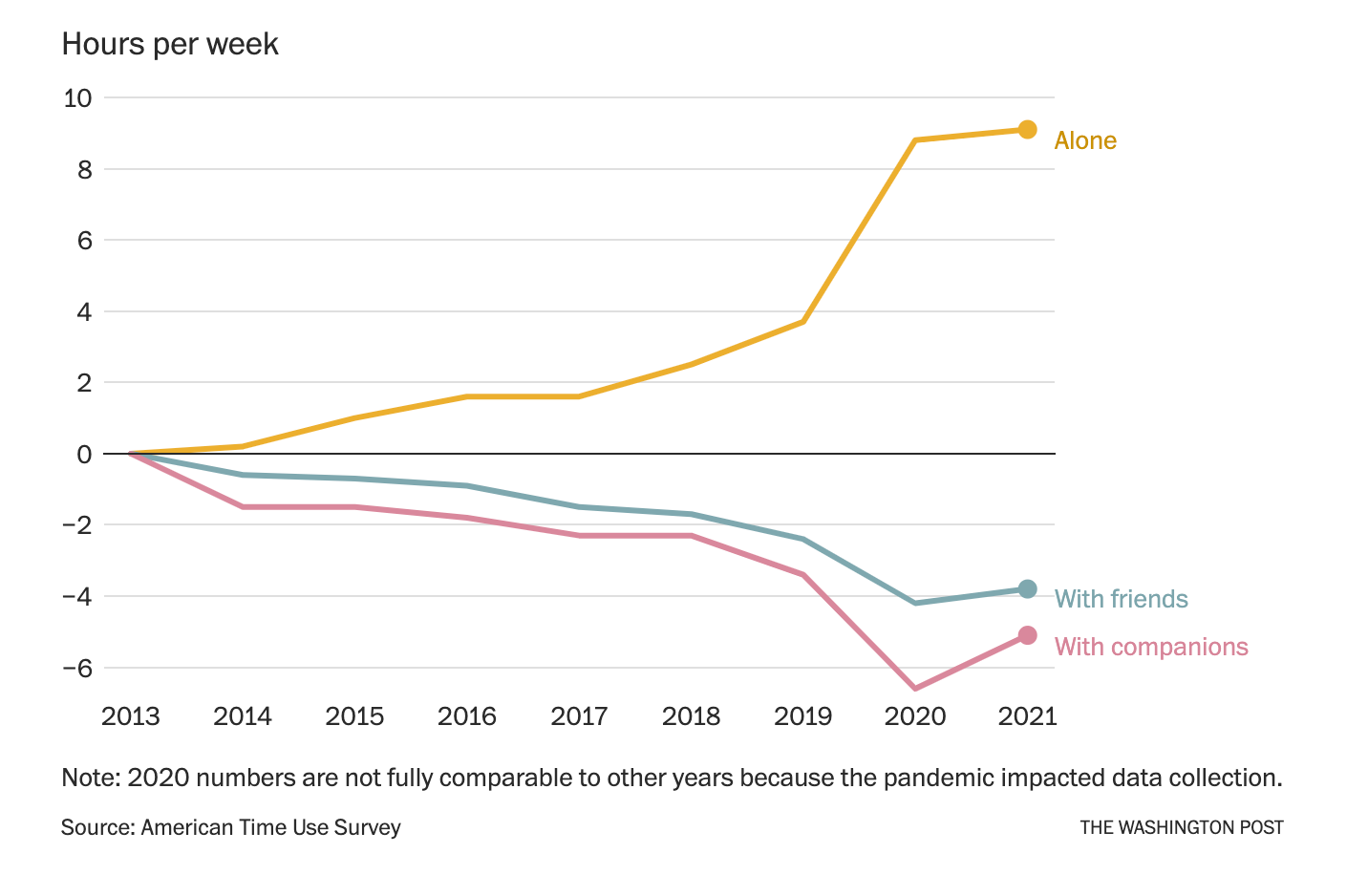

Part of the reason for the surge in mental health issues is skyrocketing loneliness, which is the second cautionary lesson. Human beings are social animals, and a compelling body of research shows that loneliness is as deadly as smoking 18 cigarettes a day. Yet data from the last year shows that, even before COVID-19, loneliness was becoming a way of life for too many. Take, for example, the Washington Post’s data on how our social time has changed in the last 10 years:

This chart, alone, explains most of the mental health problems in the United States. But it’s not just individual mental health that suffers when people are lonely. Economic productivity decreases. So, too, does innovation and creativity. (Have you noticed a decrease in the quality of movies and TV shows? Maybe it’s because “nobody in Hollywood has any friends.”)

The most damaging impact of loneliness, however, is a decline in trust, which is the third lesson of 2022. A disconnected people is a distrustful people. And, perhaps for the first time in history, every institution in American life has experienced a measured decrease in trust. We don’t trust the police (after George Floyd) or the federal government (after Trump). But we don’t trust schools, small businesses, or hospitals, either.

The most concerning decrease in trust, however, is not the distrust we have in institutions. It’s the distrust we have of each other. As I wrote earlier this year:

[T]hat is exactly where we are, as a nation: without trust. Recall the trust question in the General Social Survey; in 1972, people were split half and half between trusters, i.e., those who said “most people can be trusted,” and non-trusters, i.e., those who said “you can’t be too careful when dealing with people.”

By 2018, however, things got much worse; the non-trusters outnumbered the trusters 2:1.

We learned, in short, that the world is becoming more depressed, more lonely, and more distrustful than at any point in recent history. And this is a huge problem, not just for our health and economy, but for our hopes for human moral progress. Because a depressed, lonely, and distrustful populace is not one that is able to make change.

So then how is change happening, nonetheless? I think there are other more optimistic lessons from 2022, when you look more closely at the data.

The first is that grassroots leadership has become even more important - and grassroots leaders are stepping. One of my greatest failings when we founded DxE, in 2013, was a failure to realize the difference between a decentralized movement and a leaderless movement. The former is a source of strength; the latter is a recipe in futility. When communities or movements have thrived in 2022, it has been because of the existence of leadership — individuals with the training, talent, and commitment to bring people together despite the historic challenges we face as a species.

Two small events, recently, have demonstrated to me the power of grassroots leadership. The first was an ice cream social put together by an informal group we’ve started calling “Vegans in Tech.” It was one of the most fun and engaging events I’ve been to, in a long while, and I did almost none of the organizing. A loose crew of about a dozen local vegans put it together — and that’s why the event shined, attracting around 40 people and creating energetic, interesting, and often hilarious conversation.

The other event was a talk and vegan food serve at the SF Unitarian church. I’ve recently become a member of the church — which, unlike any other church I’ve ever heard of, is comprised mostly of atheists and agnostics — and I was invited to give a short talk on the dangers posed by factory farming after our Smithfield victory. And, in a world that seems filled with cynicism, I was astonished by the emotional power of what the Unitarian church organized.

“It’s a moving subject,” one man told me, afterwards, with tears in his eyes.Many other people responded similarly.

But it wasn’t just my presentation. It was the fact that so many leaders in the Unitarian church, most notably my friends Dolores and Bruce, came together to make the event happen. The attendees saw that that there was an organized effort by people who care within their own community. That moved them. Finding more Doloreses and Bruces and others is crucial to our ability to make change.

The second optimistic lesson is that, while institutional distrust is causing huge social problems, it’s also creating huge openings. I don’t know if revolutionary laws like AB2764 could have been introduced, in a time where mainstream political efforts had more trust. I don’t know that jurors in Utah could side with a “radical animal rights activist” against their own government, in an era where political institutions like the FBI, which was central to prosecuting me, had more credibility with ordinary people.

Our victories, in short, are the result of seizing political opportunities presented by this moment in history, which I’ve described as a “shake down” movement for human civilization. In shake down moments, while traditional institutions are falling apart, there are forks in the road that will allow us to build new ones. And our future (perhaps for hundreds or thousands of years) will depend on the decisions we make today. That is scary, but also inspiring — if we make the right choices.

The last lesson is the most important: kindness is the most powerful force for change. This might seem strange, in a world that is filled with insults and call-outs. But it is precisely when people expect aggression and hate — and find kindness instead — that the power of kindness becomes most apparent.

Our trial in Utah was a case in point. The people of Utah, and the jurors, probably expected Paul and I to come into court with one of two perspectives: manipulative insincerity, begging forgiveness for our actions; or aggressive self-righteousness, standing by our actions and condemning all those who opposed us. What they got instead was something different: radical kindness. We did not condemn the people of Utah, or even the prosecutors who sought to put us in prison. Heck, we did not even condemn the individuals who were part of the industry we were challenging. (We called one of them, turkey farmer Rick Pitman, to testify for the defense at trial!)

Instead, we attempted to change people with the power of kindness. As I wrote in my closing statement in Utah:

I am going to do something strange again. I am going to ask you not to make a decision on the technical issues. I am going to ask you to make a decision based on your conscience. Because there is so much more at stake here than just my freedom and Paul’s.

If you defend our right to rescue these sick and dying animals there will be much broader impacts.

Companies will be more compassionate towards the animals.

Government will be more responsive to complaints about animal cruelty.

And maybe, just maybe, a baby pig like Lily will not have to starve to death on the floor of a factory farm.

Animals have given us so much. They have given us food. They’ve given us their labor. They’ve even given us love. What they’ve asked of us in return, is for us to be good stewards to their welfare. You have a chance to stand for that idea. To recognize what Rick Pitman recognized – there’s a difference between stealing and rescuing an animal who needs some help. Your decision will make this world a kinder place – even for a sick baby pig.

I don’t know that kindness was the central reason the jury decided what they decided. We will find out for sure in a few weeks at the Smithfield trial summit, which we expect many of the jurors to attend. But I suspect what we will learn then, and what we should learn from 2022, is that, even in a depressing, lonely, and distrustful world, kindness has great power.

I hope you’ll work with me to deploy its power to even greater effect in 2023.

Happy New Year!