| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | This Hostile Artificial Intelligence Is Already Killing Us |

| Date | December 21, 2022 7:51 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

The great economist Simon Kuznets, who won the Nobel Prize in 1971, discovered a startling pattern in economic development in the 1960s. Through most of human history, societies that experienced rapid economic growth also saw increases in economic inequality. The agricultural revolution that began 10,000 years ago, and led to massive increases in human prosperity, also led to the development of highly unequal societies. These societies often had a single person — the chieftain, king, or dictator — controlling the wealth of an entire nation. The result was that, from colonial empires to slave plantations, economic growth was coming at the cost of the most vulnerable in society.

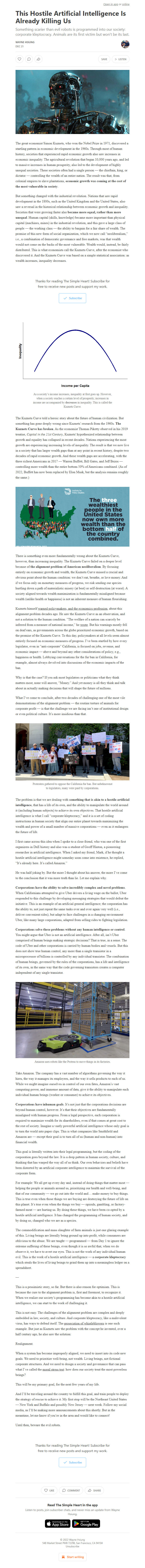

But something changed with the industrial revolution. Nations that saw rapid development in the 1800s, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, also saw a reversal in the historical relationship between economic growth and inequality. Societies that were growing faster also became more equal, rather than more unequal. Human capital (skills, knowledge) became more important than physical capital (machines, mines) in the industrial revolution, and this gave a large class of people — the working class — the ability to bargain for a fair share of wealth. The promise of this new form of social organization, which we now call “neoliberalism,” i.e., a combination of democratic governance and free markets, was that wealth would not come on the backs of the most vulnerable. Wealth would, instead, be fairly distributed. This is what economists call the Kuznets Curve, after the economist who discovered it. And the Kuznets Curve was based on a simple statistical association: as wealth increases, inequality decreases.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The Kuznets Curve told a heroic story about the future of human civilization. But something has gone deeply wrong since Kuznets’ research from the 1960s. The Kuznets Curve has broken. As the economist Thomas Piketty observed in his 2019 treatise, Capital in the 21st Century, Kuznets' hypothesized relationship between growth and equality has collapsed in recent decades. Nations experiencing the most growth are experiencing increasing levels of inequality. The result is that we now live in a society that has larger wealth gaps than at any point in recent history, despite two decades of rapid economic growth. And these wealth gaps are accelerating, with the three richest Americans in 2017 — Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos — controlling more wealth than the entire bottom 50% of Americans combined. (As of 2022, Buffett has now been replaced by Elon Musk, but the analysis remains roughly the same.)

There is something even more fundamentally wrong about the Kuznets Curve, however, than increasing inequality. The Kuznets Curve failed on a deeper level because of the alignment problem of American neoliberalism. By focusing entirely on economic growth and wealth, the Kuznets Curve missed a crucial and obvious point about the human condition: we don’t eat, breathe, or love money. And if we focus only on monetary measures of progress, we risk sending our species hurtling down a path of materialistic misery (at best) or self-destruction (at worst). A society aligned towards wealth maximization is fundamentally misaligned because wealth (unlike health or happiness) is not an inherent measure of human flourishing.

Kuznets himself warned policymakers, and the economics profession [ [link removed] ], about this alignment problem decades ago. He saw the Kuznets Curve as an observation, and not a solution to the human condition. “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income,” he wrote [ [link removed] ]. But his warnings mostly fell on deaf ears, as governments across the globe prioritized economic growth, based on the promise of the Kuznets Curve. To this day, policymakers at all levels seem almost entirely focused on economic measures of progress. I’ve been startled by how every legislator, even in “anti-corporate” California, is focused on jobs, revenue, and economic impact — above and beyond any other considerations of policy, e.g., happiness or health. Lobbying conversations for the fur ban in California, for example, almost always devolved into discussions of the economic impacts of the ban.

Why is that the case? If you ask most legislators or politicians what they think matters most, none will answer, “Money.” And yet money is all they think and talk about in actually making decisions that will shape the future of millions.

What I’ve come to conclude, after two decades of challenging one of the most vile demonstrations of the alignment problem — the routine torture of animals for corporate profit — is that the challenge we are facing isn’t one of institutional design or even political culture. It’s more insidious than that.

The problem is that we are dealing with something that is akin to a hostile artificial intelligence, that has a life of its own, and the ability to manipulate the world around it (including human subjects) to achieve its own objectives. That hostile artificial intelligence is what I call “corporate kleptocracy,” and it is a set of coding instructions in human society that align our entire planet towards maximizing the wealth and power of a small number of massive corporations — even as it endangers the future of life.

I first came across this idea when I spoke to a close friend, who was one of the first organizers in DxE history and also was a student of Geoff Hinton, a pioneering researcher in artificial intelligence. When I asked my friend, Mark, if he thought a hostile artificial intelligence might someday soon come into existence, he replied, “It’s already here. It’s called Amazon.”

He was half-joking by. But the more I thought about his answer, the more I’ve come to the conclusion that it was more truth than lie. Let me explain why.

Corporations have the ability to solve incredibly complex and novel problems. When Californians attempted to give Uber drivers a living wage on the ballot, Uber responded to this challenge by developing messaging strategies that would defeat the initiative. This is an example of an artificial general intelligence; the corporation has the ability to, not just repeat the same tasks over and over again very well (i.e., deliver convenient rides), but adapt to face challenges in a changing environment Uber, like many large corporations, adapted from selling rides to fighting legislation.

Corporations solve these problems without any human intelligence or control. You might argue that Uber is not an artificial intelligence. After all, isn’t Uber comprised of human beings making strategic decisions? That is true, in a sense. The code of Uber and other corporations is carried by human bodies and vessels. But this does not show true human control, any more than a single transistor in a microprocessor of billions is controlled by any individual transistor. The combination of human beings, governed by the rules of the corporations, has a life and intelligence of its own, in the same way that the code governing transistors creates a computer independent of any single transistor.

Take Amazon. The company has a vast number of algorithms governing the way it hires, the way it manages its employees, and the way it sells products to each of us. While we might imagine ourselves in control of our own fates, Amazon’s vast computing power, and immense amount of data, give it the ability to manipulate each individual human beings (worker or consumer) to achieve its objectives.

Corporations have inhuman goals. It’s not just that the corporations decisions are beyond human control, however. It’s that their objectives are fundamentally misaligned with human progress. From a legal perspective, each corporation is required to maximize wealth for its shareholders, even if that comes at great cost to the rest of society. Imagine a vastly powerful artificial intelligence whose only goal is to turn the world into paper clips. This is what companies like Smithfield and Amazon are — except their goal is to turn all of us (human and non-human) into financial wealth.

This goal is literally written into their legal programming, but the coding of the corporation goes beyond the law. It is a deep pattern in human society, culture, and thinking that has warped the way all of us think. Our own behaviors and beliefs have been distorted by an artificial corporate intelligence to maintain the survival of the corporate form.

For example: We all get up every day and, instead of doing things that matter most — helping the people or animals around us, prioritizing our health and well-being, and that of our community — we go out into the world and… make money to buy things. This is true even when those things we are buying are destroying the future of life on this planet. It’s true even when the things we buy — opioids, gambling, or factory-farmed meat — are hurting us. By doing these things, we have been co-opted by a hostile artificial intelligence. It has changed the programming of human society, and by doing so, changed who we are as a species.

The commodification and mass slaughter of farm animals is just one glaring example of this. Living beings are literally being ground up into profit, while consumers are oblivious to the abuse. We are taught — programmed — from Day 1 to ignore the extreme suffering of these beings, even though it is so awful that, when we do observe it, we have to avert our eyes. This is not the work of any individual human evil. This is the work of a hostile artificial intelligence — a corporate kleptocracy which steals the lives of living beings to grind them up into a meaningless ledger on a spreadsheet.

—

This is a pessimistic story, so far. But there is also reason for optimism. This is because the cure to the alignment problem is, first and foremost, to recognize it. When we realize our society’s programming has become akin to a hostile artificial intelligence, we can start to the work of challenging it.

This is not easy. The challenges of the alignment problem are complex and deeply embedded in law, society, and culture. And corporate kleptocracy, like a malevolent virus, has ways to defend itself. The prosecution of whistleblowers [ [link removed] ] is one such example. But just as Kuznets saw the problem with the concept he invented, over a half century ago, he also saw the solution:

Realignment.

When a system has become improperly aligned, we need to insert into its code new goals. We need to prioritize well-being, not wealth. Living beings, not fictional corporate structures. And we need to design a society and governance that can pass what I’ve called the moral stress test [ [link removed] ]: how does our society treat the most powerless beings?

This will be my primary goal, for the next few years of my life.

And I’ll be traveling around the country to fulfill this goal, and train people to deploy the strategy of rescue to achieve it. My first stop will be the Northeast United States — New York and Buffalo and possibly New Jersey — next week. Follow my social media, as I’ll be making more announcements about this shortly. But in the meantime, let me know if you’re in the area and would like to connect!

Until then, beware the evil robots.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

The great economist Simon Kuznets, who won the Nobel Prize in 1971, discovered a startling pattern in economic development in the 1960s. Through most of human history, societies that experienced rapid economic growth also saw increases in economic inequality. The agricultural revolution that began 10,000 years ago, and led to massive increases in human prosperity, also led to the development of highly unequal societies. These societies often had a single person — the chieftain, king, or dictator — controlling the wealth of an entire nation. The result was that, from colonial empires to slave plantations, economic growth was coming at the cost of the most vulnerable in society.

But something changed with the industrial revolution. Nations that saw rapid development in the 1800s, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, also saw a reversal in the historical relationship between economic growth and inequality. Societies that were growing faster also became more equal, rather than more unequal. Human capital (skills, knowledge) became more important than physical capital (machines, mines) in the industrial revolution, and this gave a large class of people — the working class — the ability to bargain for a fair share of wealth. The promise of this new form of social organization, which we now call “neoliberalism,” i.e., a combination of democratic governance and free markets, was that wealth would not come on the backs of the most vulnerable. Wealth would, instead, be fairly distributed. This is what economists call the Kuznets Curve, after the economist who discovered it. And the Kuznets Curve was based on a simple statistical association: as wealth increases, inequality decreases.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The Kuznets Curve told a heroic story about the future of human civilization. But something has gone deeply wrong since Kuznets’ research from the 1960s. The Kuznets Curve has broken. As the economist Thomas Piketty observed in his 2019 treatise, Capital in the 21st Century, Kuznets' hypothesized relationship between growth and equality has collapsed in recent decades. Nations experiencing the most growth are experiencing increasing levels of inequality. The result is that we now live in a society that has larger wealth gaps than at any point in recent history, despite two decades of rapid economic growth. And these wealth gaps are accelerating, with the three richest Americans in 2017 — Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos — controlling more wealth than the entire bottom 50% of Americans combined. (As of 2022, Buffett has now been replaced by Elon Musk, but the analysis remains roughly the same.)

There is something even more fundamentally wrong about the Kuznets Curve, however, than increasing inequality. The Kuznets Curve failed on a deeper level because of the alignment problem of American neoliberalism. By focusing entirely on economic growth and wealth, the Kuznets Curve missed a crucial and obvious point about the human condition: we don’t eat, breathe, or love money. And if we focus only on monetary measures of progress, we risk sending our species hurtling down a path of materialistic misery (at best) or self-destruction (at worst). A society aligned towards wealth maximization is fundamentally misaligned because wealth (unlike health or happiness) is not an inherent measure of human flourishing.

Kuznets himself warned policymakers, and the economics profession [ [link removed] ], about this alignment problem decades ago. He saw the Kuznets Curve as an observation, and not a solution to the human condition. “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income,” he wrote [ [link removed] ]. But his warnings mostly fell on deaf ears, as governments across the globe prioritized economic growth, based on the promise of the Kuznets Curve. To this day, policymakers at all levels seem almost entirely focused on economic measures of progress. I’ve been startled by how every legislator, even in “anti-corporate” California, is focused on jobs, revenue, and economic impact — above and beyond any other considerations of policy, e.g., happiness or health. Lobbying conversations for the fur ban in California, for example, almost always devolved into discussions of the economic impacts of the ban.

Why is that the case? If you ask most legislators or politicians what they think matters most, none will answer, “Money.” And yet money is all they think and talk about in actually making decisions that will shape the future of millions.

What I’ve come to conclude, after two decades of challenging one of the most vile demonstrations of the alignment problem — the routine torture of animals for corporate profit — is that the challenge we are facing isn’t one of institutional design or even political culture. It’s more insidious than that.

The problem is that we are dealing with something that is akin to a hostile artificial intelligence, that has a life of its own, and the ability to manipulate the world around it (including human subjects) to achieve its own objectives. That hostile artificial intelligence is what I call “corporate kleptocracy,” and it is a set of coding instructions in human society that align our entire planet towards maximizing the wealth and power of a small number of massive corporations — even as it endangers the future of life.

I first came across this idea when I spoke to a close friend, who was one of the first organizers in DxE history and also was a student of Geoff Hinton, a pioneering researcher in artificial intelligence. When I asked my friend, Mark, if he thought a hostile artificial intelligence might someday soon come into existence, he replied, “It’s already here. It’s called Amazon.”

He was half-joking by. But the more I thought about his answer, the more I’ve come to the conclusion that it was more truth than lie. Let me explain why.

Corporations have the ability to solve incredibly complex and novel problems. When Californians attempted to give Uber drivers a living wage on the ballot, Uber responded to this challenge by developing messaging strategies that would defeat the initiative. This is an example of an artificial general intelligence; the corporation has the ability to, not just repeat the same tasks over and over again very well (i.e., deliver convenient rides), but adapt to face challenges in a changing environment Uber, like many large corporations, adapted from selling rides to fighting legislation.

Corporations solve these problems without any human intelligence or control. You might argue that Uber is not an artificial intelligence. After all, isn’t Uber comprised of human beings making strategic decisions? That is true, in a sense. The code of Uber and other corporations is carried by human bodies and vessels. But this does not show true human control, any more than a single transistor in a microprocessor of billions is controlled by any individual transistor. The combination of human beings, governed by the rules of the corporations, has a life and intelligence of its own, in the same way that the code governing transistors creates a computer independent of any single transistor.

Take Amazon. The company has a vast number of algorithms governing the way it hires, the way it manages its employees, and the way it sells products to each of us. While we might imagine ourselves in control of our own fates, Amazon’s vast computing power, and immense amount of data, give it the ability to manipulate each individual human beings (worker or consumer) to achieve its objectives.

Corporations have inhuman goals. It’s not just that the corporations decisions are beyond human control, however. It’s that their objectives are fundamentally misaligned with human progress. From a legal perspective, each corporation is required to maximize wealth for its shareholders, even if that comes at great cost to the rest of society. Imagine a vastly powerful artificial intelligence whose only goal is to turn the world into paper clips. This is what companies like Smithfield and Amazon are — except their goal is to turn all of us (human and non-human) into financial wealth.

This goal is literally written into their legal programming, but the coding of the corporation goes beyond the law. It is a deep pattern in human society, culture, and thinking that has warped the way all of us think. Our own behaviors and beliefs have been distorted by an artificial corporate intelligence to maintain the survival of the corporate form.

For example: We all get up every day and, instead of doing things that matter most — helping the people or animals around us, prioritizing our health and well-being, and that of our community — we go out into the world and… make money to buy things. This is true even when those things we are buying are destroying the future of life on this planet. It’s true even when the things we buy — opioids, gambling, or factory-farmed meat — are hurting us. By doing these things, we have been co-opted by a hostile artificial intelligence. It has changed the programming of human society, and by doing so, changed who we are as a species.

The commodification and mass slaughter of farm animals is just one glaring example of this. Living beings are literally being ground up into profit, while consumers are oblivious to the abuse. We are taught — programmed — from Day 1 to ignore the extreme suffering of these beings, even though it is so awful that, when we do observe it, we have to avert our eyes. This is not the work of any individual human evil. This is the work of a hostile artificial intelligence — a corporate kleptocracy which steals the lives of living beings to grind them up into a meaningless ledger on a spreadsheet.

—

This is a pessimistic story, so far. But there is also reason for optimism. This is because the cure to the alignment problem is, first and foremost, to recognize it. When we realize our society’s programming has become akin to a hostile artificial intelligence, we can start to the work of challenging it.

This is not easy. The challenges of the alignment problem are complex and deeply embedded in law, society, and culture. And corporate kleptocracy, like a malevolent virus, has ways to defend itself. The prosecution of whistleblowers [ [link removed] ] is one such example. But just as Kuznets saw the problem with the concept he invented, over a half century ago, he also saw the solution:

Realignment.

When a system has become improperly aligned, we need to insert into its code new goals. We need to prioritize well-being, not wealth. Living beings, not fictional corporate structures. And we need to design a society and governance that can pass what I’ve called the moral stress test [ [link removed] ]: how does our society treat the most powerless beings?

This will be my primary goal, for the next few years of my life.

And I’ll be traveling around the country to fulfill this goal, and train people to deploy the strategy of rescue to achieve it. My first stop will be the Northeast United States — New York and Buffalo and possibly New Jersey — next week. Follow my social media, as I’ll be making more announcements about this shortly. But in the meantime, let me know if you’re in the area and would like to connect!

Until then, beware the evil robots.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a