|

The Fraud Behind Thanksgiving (Mailbag and Podcast)

Thanksgiving is based on a cruel lie. Here’s how we can turn it into something worth celebrating.

November 2015 was the end of one of the worst months of my life. My beloved cat Flash died, after being stricken by kidney disease. She spent her last moments suffering in a cage at a veterinary ICU, rather than with her family, because the vets didn’t bother telling me she was near the end. Then, just days later, my mom passed away after her cancer took a turn for the worse. I rushed home to see her, but I didn’t get to say good-bye.

But the thing that hurt me most, through this tragedy and suffering, was seeing the people around me celebrating Thanksgiving. Now it would not have been fair for me to expect them to understand my personal loss. There was, however, another more public tragedy unfolding even as I grappled with the deaths in my family. The brutal killings of 46 million sentient beings, one of whom I carried in my own arms in the moments before her death, on a day that many animal rights advocates describe as The Deadly Feast.

I am speaking, of course, of the turkeys killed this week. And the video below, taken from the highest rated farm in the Whole Foods supply chain, speaks for itself. The baby bird I removed in this video died moments later in my arms.

I have written previously about my experience with Diestel Turkey Ranch, one of only 3 farms in the entire Whole Foods supply chain that was given the highest 5+ rating in animal welfare. The company set up a sham farm, for marketing purposes, with turkeys raised in idyllic conditions outdoors; none of those animals was actually being raised for commercial slaughter. The actual birds being sold to consumers were instead raised at nearby factory farms, where thousands of animals were crammed in industrial sheds. The conditions were so brutal that, in some cases, 7% of the birds died in a single week.

We exposed this truth in 2015 in the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. And it was a huge victory, not just for Direct Action Everywhere, but for animal rights. Humanewashing – i.e., efforts by the industry to make a cruel system seem humane – became something that mainstream media outlets, and ordinary consumers, were more aware of. And it changed the animal rights movement for the better, with unprecedented numbers mobilizing to support nonviolent action against slaughterhouses and factory farms.

But animal cruelty is just one of many reasons that people are rejecting the Thanksgiving traditions. The Wampanoag tribe, whose act of generosity to American Pilgrims served as the historical inspiration for the holiday, has long considered Thanksgiving a day of mourning rather than celebration. That first feast in 1621, in which the Wampanoag brought gifts and food to desperate Pilgrims, was the beginning of a genocide that virtually wiped their people off the face of the earth.

Others are concerned about the environmental and economic consequences of Thanksgiving. While many Americans celebrate over excess food and holiday shopping, inequality across the nation and world is only worsening. Many have replaced Black Friday – the busiest shopping day of the year – with Buy Nothing Day.

|

The entire notion of Thanksgiving, in short, is arguably based on a lie. Far from a celebration of kindness and generosity, the holiday is based on cruelty, violence, and greed.

These critiques have a strong basis but, if left as only critique, miss a very important point. We cannot just reject tradition. We have to reclaim it, if we are serious about change. Adam Grant’s work on how new ideas take hold shows that change happens when innovation is wrapped in the clothing of older and more accepted ideas, a concept that Grant calls “tempered radicalism.” Gay rights, for example, became a powerful movement when it framed its radical message in traditional concepts of marriage and love, rather than more ideological messaging around anti-discrimination and LGBT rights.

But how do we do this around the Thanksgiving holiday? I’d encourage you, again, to listen to the conversation I had with Priya Sawhney for some specific examples. Both of us have had great success, not just with Thanksgiving, but with many other holidays, and with our family dynamics more generally. But there are a few simple tips I’d suggest that can help you reclaim Thanksgiving and transform it into a day where we can truly give thanks.

The first is to be honest. Too often, we try to stomach our feelings about the holiday just to get along with the people around us. This is a mistake. When we silence ourselves, our feelings still inevitably come out – just in passive aggressive ways. Priya’s story from the podcast, about leaving quietly when her friend began eating animals, is an example of that; it saved some conflict in the short term but nearly destroyed the friendship. While it might be easier to hide things, it hurts us in the long term because true relationships are based on authenticity.

|

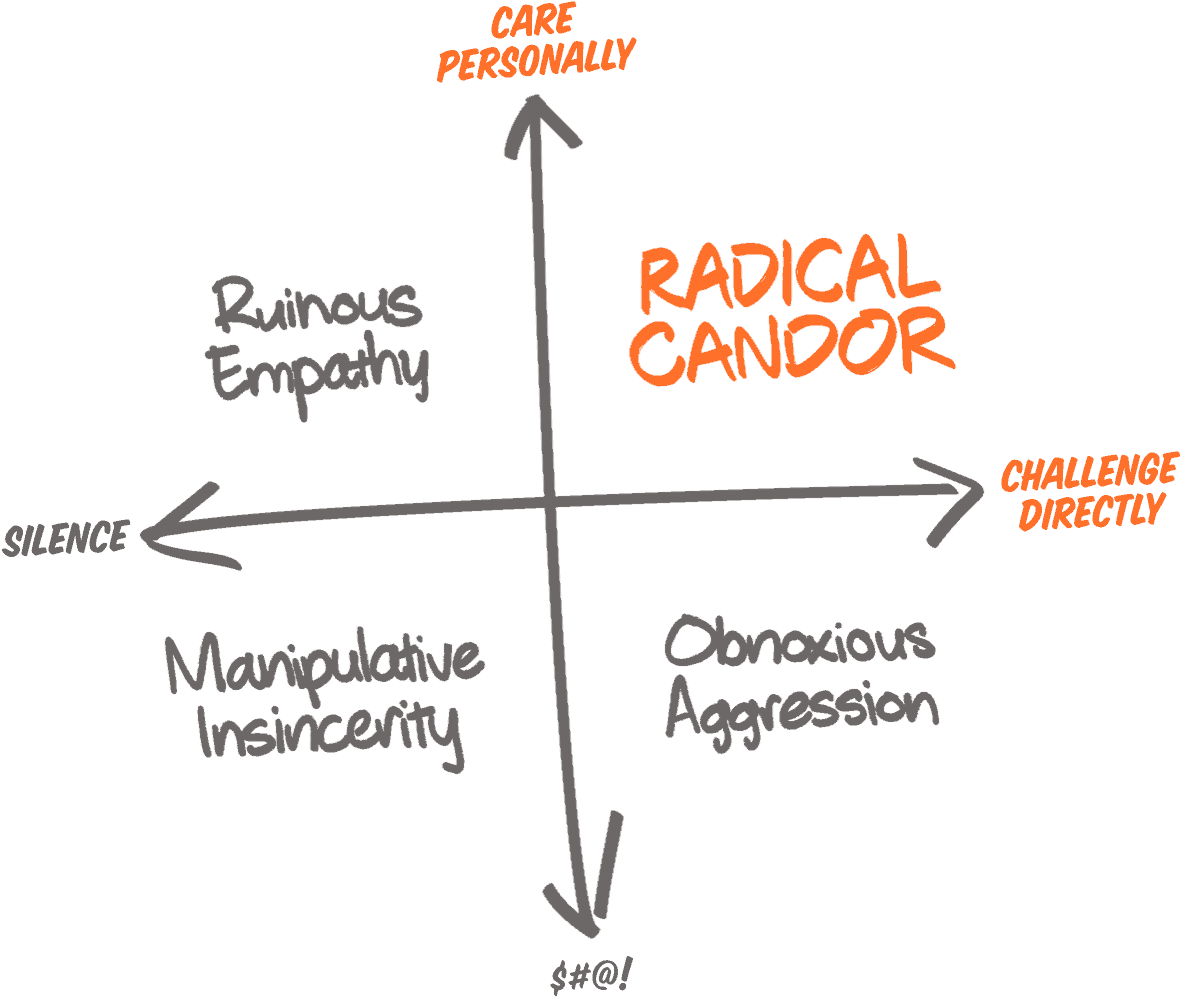

The second tip is to be as helpful as you are critical. The hard part about radical candor, when it includes some judgment of others’ actions, is that it can seem like you don’t care. In the worst case, the people around you may even perceive you as self-righteous or narcissistic. The antidote to this is to be as helpful as possible, especially when you are offering a critique. So, for example, if you are going to suggest that your family take the turkey off the menu, offer to prepare something to replace the turkey that’s plant-based – and thank everyone for their willingness to listen to your concern.

You might ask, why should I have to bear an extra burden, if I’m right? That misses the point. First, being helpful is not a burden. It’s a gift you give to others around the holidays, and to yourself. People who are kind, rather than judgmental or resentful, are happier and more fulfilled people. Second, even if your offer to help does sometimes feel like a burden – and it will, at times – remember that is just the cost of change. If you’re serious about doing good for the world, you’ll pay that cost gladly.

The third and final tip is, “Don’t do it alone.” As Priya and I discuss in the podcast, both of us have had much more success around the holidays when we showed our families that we were not the only ones who cared about animals. My family was very influenced by the fact that Priya, Jon, and others who were good and caring people shared their son’s concern about animal rights. And even if you don’t have a friend that your family respects, who can engage with your family around the holiday, rely on figures in the media that your family might respect. If your family members are scientists and atheists, note that Richard Dawkins – the famous biologist and atheist – has compared animal agriculture to human slavery. If they are huge fans of comedy, reference Ricky Gervais’s growing commitment to animal rights. The key thing is to show your family that you are not alone. The movement for animals is widespread, diverse, and growing rapidly.

So there it is. Three tips on transforming Thanksgiving: be honest; be helpful; and don’t do it alone. I’d love to hear from all of you, too, on what has worked for you. Leave a comment on the site, so everyone can hear your story!

—

Mailbag

Thanks to all of you who sent along questions for the “mailbag,” which I’m doing for the first time. If things go well, this may become a regular part of this newsletter. Here are some of the questions you asked, along with my answers.

How can a regular person new to this field be of most use or service to the movement? If we are considering even a career change, where to focus?

This is a question that is both easy and hard. The easy part of the question is to just dive in. The animal rights movement is desperately in need of human capital. And while every bit counts – donating, volunteering, or even just sharing animal rights content on social media – the highest impact people are the people who devote their lives and careers to the cause.

This is true no matter what your skill set is: fundraising, music, or even administrative work. The reason is that the movement is young, and dramatically lacks expertise. So, even if you are not incredibly skilled by global standards, you are likely as skilled as anyone else in the movement.

While I’m more hesitant to give specific advice, in terms of area of focus, I will say this: the movement needs far more people with extraordinary communications ability, and with extraordinary organizing ability. If you are, or aspire to be, a great storyteller, or a great organizer, those are both very high impact areas.

Not sure if you've already covered this in the past, but, how do you cope with being such an outsider with other humans who, generally speaking, agree with you in principle but not practice? (I'm a 43 year old contractor and, by far, the only person within the company and sometimes it feels like the only person within the whole industry that gives two shits about animals and their suffering.) How do we go about our daily lives when sometimes it seems like you're the only one who "gets it"?

This is a painfully common experience, and one made worse by the holidays. I’ve already given some tips above that can help all of us cope: be honest; be helpful; and don’t do it alone. But those approaches, while successful in the long term, may not help us cope in the short term. And while there are many specific tactics that are useful for coping – meditation, exercise, and finding a healthy community – almost all of them go under a general rubric that leadership consultant Olivia Fox has called “responsibility transfer,” i.e., accepting that we don’t control everything and understanding that a higher power is responsible for the outcomes we see in our daily lives (even when they are bad ones).

The idea behind this is very similar to the Buddhist concept of detachment, and it does not require any particular spiritual belief – or any metaphysical belief at all. For example, I am an atheist Buddhist who believes everything in our world can be described and understood by the laws of science. But I also still believe that people, including me, are shaped by a higher power. This is because of the importance of systems – policies, laws, and (above all) cultural norms – in shaping each of our individual behaviors. When you look at things from this perspective, it’s easier to cope – especially when you believe, as I do, that the systems are moving in the right direction.

The last thing I’ll say about this is related, but particularly important for animal advocates. Remember that people are animals, too. I have dealt with so many dogs over the years, for example, who have engaged in all manner of harmful behavior. The person who was most important to me in life, my dog Lisa, was a killer – and never repented for her crimes. But I still loved and accepted her because I understood, on a fundamental level, that she was a good dog — but just not totally in control of her own behavior. When we accept that human beings, like dogs, have simple hearts and simple fears, it’s easier to cope with their reluctance to change.

Thank you for your tremendous work. I appreciate your deep explanations re: legal strategy and use of the court system. I'd like to hear your perspective on if and how successes in the courts can inform new policy advocacy avenues, e.g. toward stronger and more explicit right to rescue laws, as well as expanded welfare laws for farm animals more generally. Are there implications from the legal outcomes for new approaches to local, state, and/or Federal policy reform?

This is a great question that is not for me to answer, alone. The movement will take the momentum for these court cases in all sorts of directions that are unexpected. One example: when we showed Katy Tang, a legislator in San Francisco, our Operation Deathstar virtual reality experience inside the nation’s largest pig farm, she was deeply moved. But the specific policy we ultimately focused on was not pig farming, or even food animals at all, but fur. The rest, including a ban on fur across the entire state of California, is history.

Trials, and the drama and support they generate, are batteries for the movement. We can harness the energy behind them to do all sorts of good things, in terms of policy. But if there were one specific policy that I think the movement needs to focus more of its attention on, it is the so-called “right to rescue.” These are laws, such as California’s PC 597e, that give Good Samaritans the right to aid animals in need.

They are vitally important for two reasons. First, the very recognition that these laws are important is an implicit acknowledgment of the widespread abuse of animals across the nation.Second, the laws will aid the movement in building further power, by supporting activists who are doing grassroots work to expose abuse or rescue animals.

Rescue is the defining action of the animal rights movement, and it generates immense public support. The only reason far greater numbers don’t join us in mass rescues is because of fear of prosecution. Right to rescue laws will reduce this fear and enhance our movement’s ability to do more, and more powerful, open rescues.

There is a historical parallel for this sort of policy being important to movement success, moreover. The renowned historian Eric Foner has written about the crucial importance of so-called personal liberty laws – bills that were passed to protect fugitive slaves, and those who aided them – to super charging the movement for the abolition of slavery. These laws, which supported the right of ordinary citizens to aid people fleeing slavery, were crucial to the Underground Railroad, and to the developing concept of “practical abolition,” i.e., bringing the abolition of slavery into reality through personal action. Practical abolition was the touchstone of the antislavery movement, and crucial to mobilizing millions of Americans to fight for change. They saw, with their own eyes, and with their own hands, that change was possible.

Perhaps the animal rights movement needs a similar concept: practical liberation. I hope many grassroots activists will take up the mantle of the right to rescue – and bring practical liberation to life.

How does our ability to connect with our own true self impact our ability to connect with others? What prevents us from connecting with ourself or others? What practices cultivate connected presence? How do we know if we are being authentic vs "playing a part" even if we believe what what we are espousing is noble?

Stay tuned for more on this last question, as my next blog post will be on the subject “How to Connect.” I’ve learned a lot about this subject, and it was the topic that people requested in the most recent survey.

–

Some other notes and upcoming events:

Reminder that the first open rescue workshop I am leading in 4 years is occurring on Saturday, Dec 3, from 1-5 pm in SF. Here’s the event page. Register now as space is limited! I am particularly interested in having you join this if you are interested in storytelling, as we need people who are not only direct rescuers, but who can tell the stories of rescue to the world.

If you are into tech or science, I’m also organizing an ice cream social for veg*ns in tech on Saturday, Dec 10, from 7-9 pm. The Idea is to bring people together around a shared identity, and one that is very important to the Bay Area (and the world). Here’s the event page. We’re also looking for people who want to help organize this and similar future events.

I’ll be speaking at Unitarian Universalist Forum in SF on Sunday, Dec 11 from 9:30 - 11 am on How Factory Farming Endangers the Future. We’ll probably livestream the talk. But as always, hope you can appear in person. I am very grateful for the opportunity to speak to such a progressive and compassionate audience. Here’s the event page.

Let me know if you have other questions for future mailbags, and what you thought of this edition. If people like the mailbag, I’ll continue to make it part of the newsletter and blog.

That’s all for now. Hope you all have a great holiday!