Email

Four big reasons for the Census Bureau to end prison gerrymandering in 2030

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Four big reasons for the Census Bureau to end prison gerrymandering in 2030 |

| Date | November 21, 2022 6:20 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

We joined 35 other organizations calling on the Census Bureau to end prison gerrymandering

Prison Gerrymandering Project for November 21, 2022 The 2020 Census counted more than 2 million people in the wrong place. How does your voice in government suffer as a result?

Advocates to Census Bureau: End prison gerrymandering in 2030 [[link removed]] Roughly half the country now lives in a place that has taken action to address prison gerrymandering. [[link removed]]

by Aleks Kajstura and Mike Wessler

Last week, the Census Bureau wrapped up its first public comment period [[link removed]]on ways it can improve the next Census. It was our first opportunity of the decade to make the case that the Bureau should finally end prison gerrymandering nationwide in 2030. Prison gerrymandering is a problem created by the Bureau counting incarcerated people as residents of prison cells rather than their home communities. Then, when states use those Census counts to draw legislative districts, they unfairly give people who live closest to prisons a louder voice in government, to the detriment of everyone else. Our official comments gave the Bureau plenty to reconsider.

In two letters — one cosigned by 35 other criminal justice and voting rights organizations [[link removed]] and one we submitted on our own [[link removed]] — we made comprehensive arguments why the Bureau should change its process, focusing particularly on four key areas:

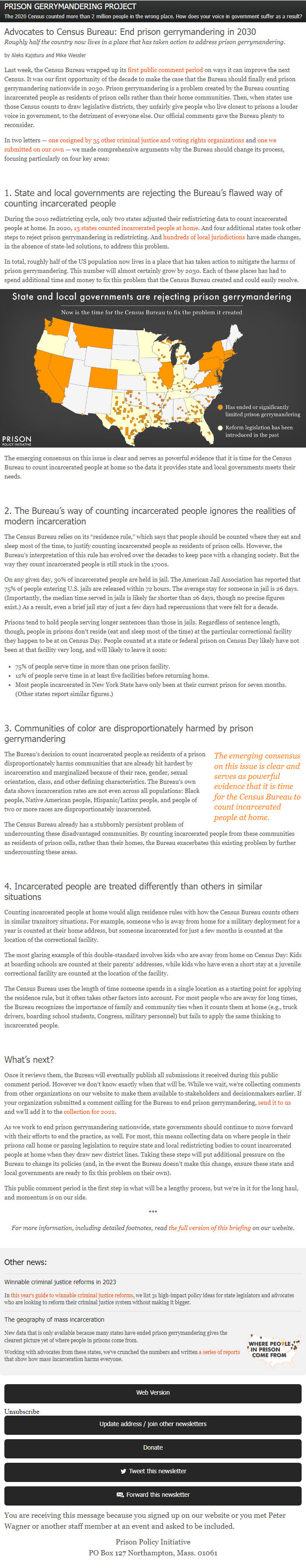

1. State and local governments are rejecting the Bureau’s flawed way of counting incarcerated people

During the 2010 redistricting cycle, only two states adjusted their redistricting data to count incarcerated people at home. In 2020, 13 states counted incarcerated people at home [[link removed]]. And four additional states took other steps to reject prison gerrymandering in redistricting. And hundreds of local jurisdictions [[link removed]] have made changes, in the absence of state-led solutions, to address this problem.

In total, roughly half of the US population now lives in a place that has taken action to mitigate the harms of prison gerrymandering. This number will almost certainly grow by 2030. Each of these places has had to spend additional time and money to fix this problem that the Census Bureau created and could easily resolve.

The emerging consensus on this issue is clear and serves as powerful evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home so the data it provides state and local governments meets their needs.

2. The Bureau’s way of counting incarcerated people ignores the realities of modern incarceration

The Census Bureau relies on its “residence rule,” which says that people should be counted where they eat and sleep most of the time, to justify counting incarcerated people as residents of prison cells. However, the Bureau’s interpretation of this rule has evolved over the decades to keep pace with a changing society. But the way they count incarcerated people is still stuck in the 1700s.

On any given day, 30% of incarcerated people are held in jail. The American Jail Association has reported that 75% of people entering U.S. jails are released within 72 hours. The average stay for someone in jail is 26 days. (Importantly, the median time served in jails is likely far shorter than 26 days, though no precise figures exist.) As a result, even a brief jail stay of just a few days had repercussions that were felt for a decade.

Prisons tend to hold people serving longer sentences than those in jails. Regardless of sentence length, though, people in prisons don’t reside (eat and sleep most of the time) at the particular correctional facility they happen to be at on Census Day. People counted at a state or federal prison on Census Day likely have not been at that facility very long, and will likely to leave it soon:

75% of people serve time in more than one prison facility. 12% of people serve time in at least five facilities before returning home. Most people incarcerated in New York State have only been at their current prison for seven months. (Other states report similar figures.)

3. Communities of color are disproportionately harmed by prison gerrymandering

The emerging consensus on this issue is clear and serves as powerful evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home.The Bureau’s decision to count incarcerated people as residents of a prison disproportionately harms communities that are already hit hardest by incarceration and marginalized because of their race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and other defining characteristics. The Bureau’s own data shows incarceration rates are not even across all populations: Black people, Native American people, Hispanic/Latinx people, and people of two or more races are disproportionately incarcerated.

The Census Bureau already has a stubbornly persistent problem of undercounting these disadvantaged communities. By counting incarcerated people from these communities as residents of prison cells, rather than their homes, the Bureau exacerbates this existing problem by further undercounting these areas.

4. Incarcerated people are treated differently than others in similar situations

Counting incarcerated people at home would align residence rules with how the Census Bureau counts others in similar transitory situations. For example, someone who is away from home for a military deployment for a year is counted at their home address, but someone incarcerated for just a few months is counted at the location of the correctional facility.

The most glaring example of this double-standard involves kids who are away from home on Census Day: Kids at boarding schools are counted at their parents’ addresses, while kids who have even a short stay at a juvenile correctional facility are counted at the location of the facility.

The Census Bureau uses the length of time someone spends in a single location as a starting point for applying the residence rule, but it often takes other factors into account. For most people who are away for long times, the Bureau recognizes the importance of family and community ties when it counts them at home (e.g., truck drivers, boarding school students, Congress, military personnel) but fails to apply the same thinking to incarcerated people.

What’s next?

Once it reviews them, the Bureau will eventually publish all submissions it received during this public comment period. However we don’t know exactly when that will be. While we wait, we’re collecting comments from other organizations on our website to make them available to stakeholders and decisionmakers earlier. If your organization submitted a comment calling for the Bureau to end prison gerrymandering, send it to us [mailto:[email protected]] and we’ll add it to the collection for 2022 [[link removed]].

As we work to end prison gerrymandering nationwide, state governments should continue to move forward with their efforts to end the practice, as well. For most, this means collecting data on where people in their prisons call home or passing legislation to require state and local redistricting bodies to count incarcerated people at home when they draw new district lines. Taking these steps will put additional pressure on the Bureau to change its policies (and, in the event the Bureau doesn’t make this change, ensure these state and local governments are ready to fix this problem on their own).

This public comment period is the first step in what will be a lengthy process, but we’re in it for the long haul, and momentum is on our side.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, read the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Winnable criminal justice reforms in 2023 [[link removed]]

In this year's guide to winnable criminal justice reforms [[link removed]], we list 31 high-impact policy ideas for state legislators and advocates who are looking to reform their criminal justice system without making it bigger.

The geography of mass incarceration [[link removed]]

New data that is only available because many states have ended prison gerrymandering gives the clearest picture yet of where people in prisons come from.

Working with advocates from these states, we've crunched the numbers and written a series of reports [[link removed]] that show how mass incarceration harms everyone.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Gerrymandering Project for November 21, 2022 The 2020 Census counted more than 2 million people in the wrong place. How does your voice in government suffer as a result?

Advocates to Census Bureau: End prison gerrymandering in 2030 [[link removed]] Roughly half the country now lives in a place that has taken action to address prison gerrymandering. [[link removed]]

by Aleks Kajstura and Mike Wessler

Last week, the Census Bureau wrapped up its first public comment period [[link removed]]on ways it can improve the next Census. It was our first opportunity of the decade to make the case that the Bureau should finally end prison gerrymandering nationwide in 2030. Prison gerrymandering is a problem created by the Bureau counting incarcerated people as residents of prison cells rather than their home communities. Then, when states use those Census counts to draw legislative districts, they unfairly give people who live closest to prisons a louder voice in government, to the detriment of everyone else. Our official comments gave the Bureau plenty to reconsider.

In two letters — one cosigned by 35 other criminal justice and voting rights organizations [[link removed]] and one we submitted on our own [[link removed]] — we made comprehensive arguments why the Bureau should change its process, focusing particularly on four key areas:

1. State and local governments are rejecting the Bureau’s flawed way of counting incarcerated people

During the 2010 redistricting cycle, only two states adjusted their redistricting data to count incarcerated people at home. In 2020, 13 states counted incarcerated people at home [[link removed]]. And four additional states took other steps to reject prison gerrymandering in redistricting. And hundreds of local jurisdictions [[link removed]] have made changes, in the absence of state-led solutions, to address this problem.

In total, roughly half of the US population now lives in a place that has taken action to mitigate the harms of prison gerrymandering. This number will almost certainly grow by 2030. Each of these places has had to spend additional time and money to fix this problem that the Census Bureau created and could easily resolve.

The emerging consensus on this issue is clear and serves as powerful evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home so the data it provides state and local governments meets their needs.

2. The Bureau’s way of counting incarcerated people ignores the realities of modern incarceration

The Census Bureau relies on its “residence rule,” which says that people should be counted where they eat and sleep most of the time, to justify counting incarcerated people as residents of prison cells. However, the Bureau’s interpretation of this rule has evolved over the decades to keep pace with a changing society. But the way they count incarcerated people is still stuck in the 1700s.

On any given day, 30% of incarcerated people are held in jail. The American Jail Association has reported that 75% of people entering U.S. jails are released within 72 hours. The average stay for someone in jail is 26 days. (Importantly, the median time served in jails is likely far shorter than 26 days, though no precise figures exist.) As a result, even a brief jail stay of just a few days had repercussions that were felt for a decade.

Prisons tend to hold people serving longer sentences than those in jails. Regardless of sentence length, though, people in prisons don’t reside (eat and sleep most of the time) at the particular correctional facility they happen to be at on Census Day. People counted at a state or federal prison on Census Day likely have not been at that facility very long, and will likely to leave it soon:

75% of people serve time in more than one prison facility. 12% of people serve time in at least five facilities before returning home. Most people incarcerated in New York State have only been at their current prison for seven months. (Other states report similar figures.)

3. Communities of color are disproportionately harmed by prison gerrymandering

The emerging consensus on this issue is clear and serves as powerful evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home.The Bureau’s decision to count incarcerated people as residents of a prison disproportionately harms communities that are already hit hardest by incarceration and marginalized because of their race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and other defining characteristics. The Bureau’s own data shows incarceration rates are not even across all populations: Black people, Native American people, Hispanic/Latinx people, and people of two or more races are disproportionately incarcerated.

The Census Bureau already has a stubbornly persistent problem of undercounting these disadvantaged communities. By counting incarcerated people from these communities as residents of prison cells, rather than their homes, the Bureau exacerbates this existing problem by further undercounting these areas.

4. Incarcerated people are treated differently than others in similar situations

Counting incarcerated people at home would align residence rules with how the Census Bureau counts others in similar transitory situations. For example, someone who is away from home for a military deployment for a year is counted at their home address, but someone incarcerated for just a few months is counted at the location of the correctional facility.

The most glaring example of this double-standard involves kids who are away from home on Census Day: Kids at boarding schools are counted at their parents’ addresses, while kids who have even a short stay at a juvenile correctional facility are counted at the location of the facility.

The Census Bureau uses the length of time someone spends in a single location as a starting point for applying the residence rule, but it often takes other factors into account. For most people who are away for long times, the Bureau recognizes the importance of family and community ties when it counts them at home (e.g., truck drivers, boarding school students, Congress, military personnel) but fails to apply the same thinking to incarcerated people.

What’s next?

Once it reviews them, the Bureau will eventually publish all submissions it received during this public comment period. However we don’t know exactly when that will be. While we wait, we’re collecting comments from other organizations on our website to make them available to stakeholders and decisionmakers earlier. If your organization submitted a comment calling for the Bureau to end prison gerrymandering, send it to us [mailto:[email protected]] and we’ll add it to the collection for 2022 [[link removed]].

As we work to end prison gerrymandering nationwide, state governments should continue to move forward with their efforts to end the practice, as well. For most, this means collecting data on where people in their prisons call home or passing legislation to require state and local redistricting bodies to count incarcerated people at home when they draw new district lines. Taking these steps will put additional pressure on the Bureau to change its policies (and, in the event the Bureau doesn’t make this change, ensure these state and local governments are ready to fix this problem on their own).

This public comment period is the first step in what will be a lengthy process, but we’re in it for the long haul, and momentum is on our side.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, read the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Winnable criminal justice reforms in 2023 [[link removed]]

In this year's guide to winnable criminal justice reforms [[link removed]], we list 31 high-impact policy ideas for state legislators and advocates who are looking to reform their criminal justice system without making it bigger.

The geography of mass incarceration [[link removed]]

New data that is only available because many states have ended prison gerrymandering gives the clearest picture yet of where people in prisons come from.

Working with advocates from these states, we've crunched the numbers and written a series of reports [[link removed]] that show how mass incarceration harms everyone.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor