Nov. 15, 2022

Permission to republish original opeds and cartoons granted.

Unemployment ticks up as 328,000 jobs lost in October and inflation cools with 2024 looming

<

< By Robert Romano

The U.S. economy shed 328,000 jobs in October, raising the national unemployment rate to 3.7 percent as inflation cooled to 7.7 percent annualized, the latest employment and price data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows.

This is what usually happens at the end of economic cycles after peak employment has been reached and the economy overheats. Prices get too high from the inflation and as consumers spend more on food and energy, they spend less on other items, including putting off larger purchases for later, resorting to credit cards for basic household needs until finally, consumer spending contracts along with prices.

That’s when the recession strikes. Businesses, seeing weaker demand, first stop hiring and then begin laying off employees.

Sure enough, job openings are down 1.1 million from their March 2022 peak of 11.8 million.

And this is the third time this year that BLS has recorded jobs losses in the household survey: 353,000 in April, 315,000 in June and now 328,000 in October. Those losses were more than offset by gains in all the other months.

Historically, drops in inflation have coincided with increases in unemployment, the most extreme example being the Great Depression, when deflation consumed the U.S. and global economy as the interwar gold standard fell apart at the seams.

Back then, the U.S. dollar was way too strong as foreign trade partners like Great Britain moved off of the gold standard, artificially strengthening the dollar and sending the economy into a crash landing. The Great Depression dragged on for years not because of government intervention or tariffs per se, but because of the failure to recognize the adverse impact of keeping the dollar exchange rate to gold so high while the rest of the world was engaged in competitive devaluation and retiring the interwar gold standard.

Deflation in the U.S. began after the great inflation of World War I and the ensuing credit expansion, had a brief respite in the 1920s before beginning again in 1927. It then slowed in 1929, and then went crazy starting in 1930 as banks began failing en masse. Inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931, -10.3 percent in 1932 and -5.2 percent in 1933.

As that occurred, unemployment skyrocketed, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent.

The United Kingdom had a similar experience of deflation following World War I, with unemployment rising dramatically in 1921 to 11 percent before dropping and again rising in 1930 to 11 percent. The UK quickly came off the gold standard in 1931, after which unemployment peaked in 1932 at 15 percent, before slowly coming back down.

It was not until Franklin Roosevelt ended the interwar gold standard in 1933 that some relief was felt in The U.S. as unemployment began collapsing down to 11 percent by 1937 before spiking again in the 1937-38 recession as deflation ensued again. Ultimately, the ongoing problems were not fully alleviated until the massive mobilization of World War II.

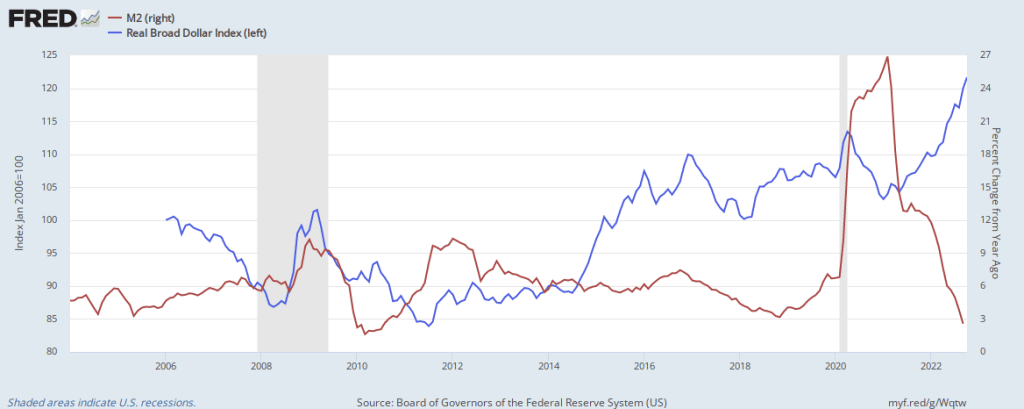

During Covid, a similar pattern emerged as the global economy shut down and the value of the dollar soared to its highest levels on record at the time, and 25 million jobs were lost. So, the Fed took interest rates to near-zero percent and central banks and financial institutions purchased a ton of U.S. treasuries to shore up the U.S. economy amid a $6 trillion spending and printing binge. The dollar weakened, and unemployment collapsed in record time.

We halted production and expanded the money supply dramatically at the same moment — too much money chasing too few goods. What else were prices supposed to do?

Now, after all the printing, and the high inflation, the Fed has hiked interest rates to 3.75 percent to 4 percent, with more hikes on the horizon to fight the inflation, stabilizing the M2 money supply, albeit at a much higher level, and which could even begin contracting on an annualized basis for the first time since — well, ever. It’s never contracted in the entire history of the Fed’s dataset going back to 1959.

As interest rates have risen, combined with the ongoing, Covid-induced global supply crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, so too has the value of the U.S. dollar risen against foreign trade partners, sending the value of the dollar even higher than during Covid, only coming off those highs in the past few weeks.

But with more interest rate hikes to come to combat the inflation as global production still lags behind demand, there appears to be no offset to prevent the dollar from getting even stronger than it already is.

Could all that spark deflation?

One looming factor to consider are the current labor shortages as Baby Boomers retire en masse. There are still 10 million job openings — and now way to fill them. Meaning, the production shortfalls we are experiencing will be ongoing, and meeting demand will continue to be a challenge.

That is, until employers give up on expansion and the layoffs really begin in earnest. It could be somewhat muted by the retirement wave — in advanced economies like Japan with aging populations peaks in the unemployment rate during recessions have tended to be much lower than in the U.S. — but all of that unemployment is still on the horizon. The rate is already increasing, but by how much remains to be seen.

Politically, in the U.S., recessions have often been a catalyst for change, resulting in one-term presidents including Herbert Hoover in 1932, Jimmy Carter in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1992 and Donald Trump in 2020. To fight the recession and unemployment, President Joe Biden will be tempted to weaken the dollar and stimulate the economy via more government spending, and the Fed via quantitative easing, at least until after 2024.

With Republicans taking control of the House in the 2022 midterms, big spending bills might not be possible as gridlock ensues, thereby controlling the growth of the money supply on the fiscal side.

It's a crossroads. Down one road is recession, and down the other is more inflation, leading to another recession, perhaps larger, even further away.

Choose your poison.

This could result in political pressure from the White House on the Fed to lower interest rates and purchase more treasuries as unemployment rises. For now, the Fed seems to be saying it will cross that bridge when it gets to it, instead focusing on taming the inflation, even if it means a recession now rather than later. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

To view online: https://dailytorch.com/2022/11/unemployment-ticks-up-as-328000-jobs-lost-in-october-and-inflation-cools-with-2024-looming/

Cartoon: Marching Orders

By A.F. Branco

Click here for a higher level resolution version.

J.D. Vance: Don't Blame Trump

By J.D. Vance

Something odd happened on Election Day. In the morning, we were confident of my victory in Ohio and cautiously optimistic about the rest of the country. By the time the polls closed, that optimism had turned to jubilance—and lobbying.

Every consultant and personality I encountered during my campaign claimed credit for their own faction. The victory was a testament to Mitch McConnell’s Senate Leadership Fund (SLF), one person told me. Another argued instead that SLF had actually bungled the race, and the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC)—chaired by Rick Scott—deserved the credit. (Full disclosure: both the NRSC and SLF helped my race in Ohio, for which I’m grateful.)

But then the results rolled in, and it was clear the outcome was far more disappointing than hoped. And every person claiming victory on Tuesday morning knew exactly who to blame on Tuesday night: Donald J. Trump.

Of course, no man is above criticism. But the quick turn from gobbling up credit to vomiting blame suggests there is very little analysis at work. So let’s try some of that.

Let’s start with an obvious caveat: there is a lot we don’t know. Precinct level data is still outstanding in most states, and exit polls are notoriously finicky. Votes are still being counted out west. We’re still ignorant about a lot. But any effort to blame Trump—or McConnell for that matter—ignores a major structural advantage for Democrats: money. Money is how candidates fund the all-important advertising that reaches swing voters, and it’s how candidates fund turnout operations. And in every marquee national race, Republicans got crushed financially.

The reason is ActBlue. ActBlue is the Democrats’ national fundraising platform, where 21 million individual donors shovel small donations into every marquee national race. ActBlue is why my opponent ran nonstop ads about how much he “agreed with Trump” during the summer. It is why John Fetterman was able to raise $75 million for his election.

Republican small dollar fundraising efforts are paltry by comparison, and Republican fundraising efforts suffer from high consultant and “list building” fees—where Republicans pay a lot to acquire small-dollar donors. This is why incumbents have such massive advantages: much of the small-dollar fundraising my own campaign did went to fundraising and list-building expenses. If and when I run for reelection, almost all of it will go directly to my campaign. Democrats don’t have this problem. They raise more money from more donors, with lower overhead.

Outside groups, like SLF, try to close this gap. But it is a losing proposition. Under federal elections law, campaigns pay way less for advertising than outside “Super PACs.” In some states, $10 million from an outside group is less efficient than $2 million spent by a campaign. So long as Republicans lose so badly in the small dollar fundraising game, Democrats will have a massive structural advantage.

Importantly, because ActBlue diverts resources to competitive races, this structural advantage can be magnified. Let’s look at how this played out specifically. At first blush, Ron DeSantis and Brian Kemp are similar figures: they both won close elections in 2018, and both cruised to reelection in 2022. They are both popular, effective governors from the South. But one won by over 20, and one by 8 (still an impressive margin). What explains this? Money. Look at the fundraising totals: Ron DeSantis outraised Charlie Crist about 7:1. Kemp was actually outraised, albeit barely, by Stacey Abrams. Money, of course, is not dispositive—Kemp won convincingly—but it has a major effect.

In both cases, incumbency provided a major advantage, in part because it’s easier to raise money when you’ve already won. But incumbency is also powerful in and of itself. Just look to Iowa, where incumbent governor Kim Reynolds cruised to reelection by a 20 point-margin, while newcomer Republican A.G. candidate Brenna Bird won by less than one point against twenty-eight-year incumbent Democrat Tom Miller.

This brings us to the Senate. In competitive states, every non-incumbent candidate was swamped with cash by national Democrats. This is true for Trump-aligned candidates (like me), anti-Trump candidates (like Joe O’Dea in Colorado), and those who straddled both camps. The house tells a similar story. Every person blaming Donald Trump, or bad candidates endorsed by Trump, ought to show a single national marquee race where a non-incumbent beat a well-funded opponent. The few exceptions—New York among them—don’t tell an easy anti-Trump story.

In Ohio, for example, Republican candidates ran against extremely well-funded Democrat opposition. Some of them were MAGA. Some establishment. Almost all of them lost. The only exception was Max Miller in Northeast Ohio, one of Trump’s early endorsements.

There is a related structural problem, which is that higher propensity voters (suburban whites, especially) are just more and more Democratic. Meanwhile, a lot of the Trump base just doesn’t turn out in midterm elections. Again, this is not unique to Trump: these voters have always had substandard turnout numbers. But 20 years ago, when most of them voted for Democrats, that meant Republicans had a structural advantage in midterms. Now, the shoe is on the other foot. This problem is exacerbated by Democrats’ strong advantages in states that have expanded vote by mail.

In the short term, as illustrated last week, those advantages serve as a reminder of the need for voting reform in this country, modeled on success in states like Ohio at running clean, fair elections: establishing fair but appropriately narrow windows to return ballots; implementing signature verification; conducting all pre-election work necessary to facilitate rapid tabulation of early votes when polls close; and implementing national photo ID requirements to ensure elections are secure.

In the long term, the way to solve this is to build a turnout machine, not gripe at the former president. But building a turnout machine without organized labor and amid declining church attendance is no small thing. Our party has one major asset, contra conventional wisdom, to rally these voters: President Donald Trump. Now, more than ever, our party needs President Trump’s leadership to turn these voters out and suffers for his absence from the stage.

The point is not that Trump is perfect. I personally would have preferred an endorsement of Lou Barletta over Mastriano in the Pennsylvania governor’s race, for example. But any effort to pin blame on Trump, and not on money and turnout, isn’t just wrong. It distracts from the actual issues we need to solve as a party over the long term. Indeed, one of the biggest changes I would like to see from Trump’s political organization—whether he runs for president or not—is to use their incredible small dollar fundraising machine for Trump-aligned candidates, which it appears he has begun doing to assist Herschel Walker in his Senate runoff.

Blaming Trump isn’t just wrong on the facts, it is counterproductive. Any autopsy of Republican underperformance ought to focus on how to close the national money gap, and how to turn out less engaged Republicans during midterm elections. These are the problems we have, and rather than blaming everyone else, it’s time for party leaders to admit we have these problems and work to solve them.

J.D. Vance is a United States senator-elect from Ohio.

To view online: https://www.theamericanconservative.com/dont-blame-trump/