|

Future Generations Will Deplore Our Cruelty to Animals. Here's the Proof.

Moral asymmetries, strategic ignorance, and preference falsification are all indicators that history will judge us harshly for our mistreatment of animals.

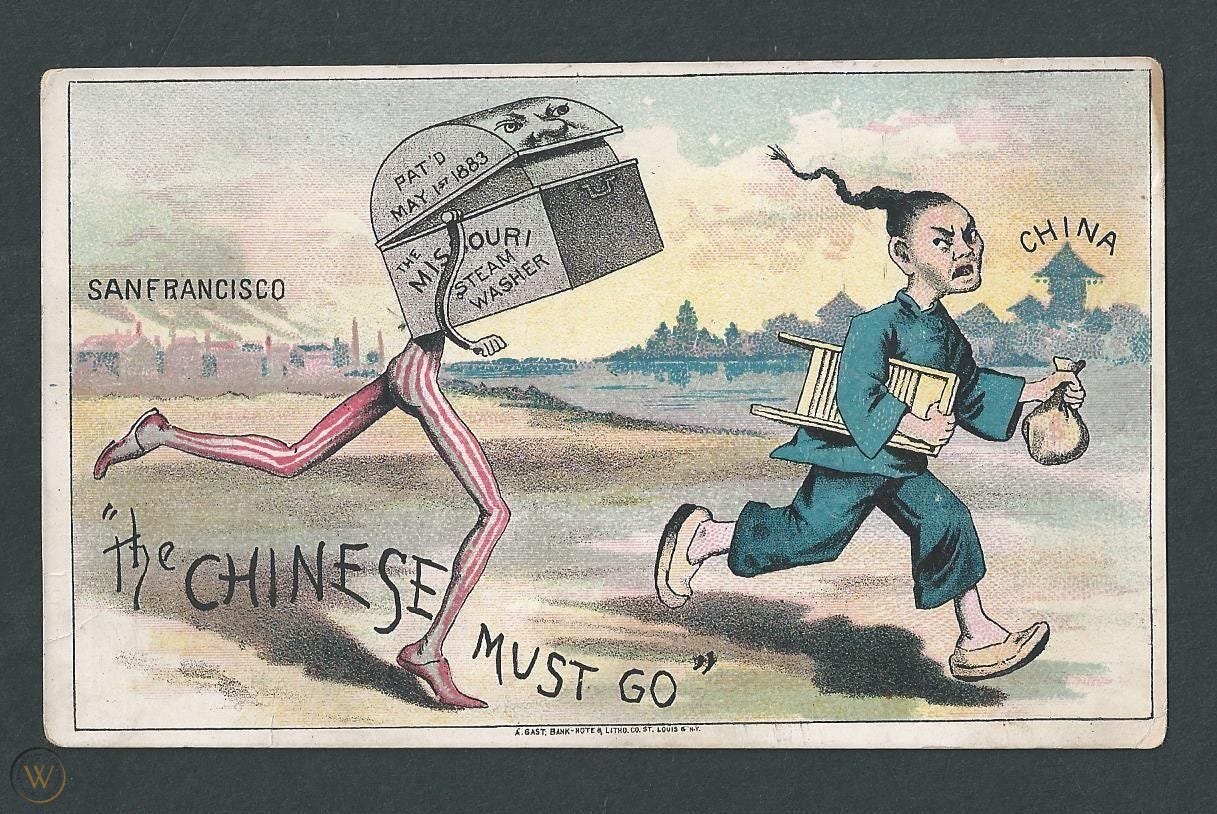

There are no true progressives. History shows this to be true. Future generations inevitably look back on each prior generation with horror. Things that seem inconsequential in one generation are condemned as atrocities in the next. Consider the last four generations.

Zoom back 50 years to 1972, and those advocating for marriage equality were condemned as outlaws and perverts. Now we look back on those days with shame.

Zoom back another 50 years to 1922, and institutional racism was not just widespread: it was culturally ascendant. The film Birth of a Nation, described recently as “the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history,” showcased Black Americans as predators who would rape or kill white woman. In one of the most famous scenes, a white actor in blackface chases and attempts to rape a white woman, who leaps off a cliff to her death.

This blatant racism was not just tolerated. It made the film into the most watched film, at the time, in American history. It’s hard to believe that it was just 100 years ago.

Zoom back another 50 years, and we are in 1872, decades before women have earned the right to vote. Susan B. Anthony decides to vote in the 1872 Presidential election, anyways, and she is arrested for doing so. While she escapes jail time despite her conviction, the poll workers who allowed her to vote are imprisoned. As millions of women vote today, it’s important to remember this history. (The entire wikipedia page on the trial is well worth a read.)

Finally, zoom back another 50 years, and we are in the year 1822, approximately ten years before the founding of the American Antislavery Society. It is considered relatively uncontroversial that human beings of color can be the property of other human beings. Their lives, their freedom, even their children are not their own. While it seems incomprehensible to us today, people did not just defend this horrific institution in 1822. They fought and died to prevent it from changing.

In every one of these time periods, even those who were considered progressives and social reformers in their time — like Thomas Jefferson, who himself owned slaves — have been judged harshly by history. And so it will be in our generation.

And interestingly, virtually every time I have seen a writer or thinker try to list the ways in which modern society will be condemned by future generations, animal rights is at the top of the list. Consider this op-ed by Nicholas Kristof in The New York Times, at the height of the George Floyd Protests:

As we pull down controversial statues and reassess historical figures, I’ve been wondering what our great-grandchildren will find bewilderingly immoral about our own times — and about us.

Which of today’s heroes will be discredited? Which statues toppled? What will later generations see as our own ethical blind spots?

I believe that one will be our cruelty to animals. Modern society relies on factory farming to produce protein that is inexpensive and abundant. But it causes suffering to animals on an incalculable scale.

|

Or consider historian Rutger Bregman’s recent statement in support of animal rights. I have followed Bregman for quite some time, due to his work on inequality. (He’s most famous for causing a viral meltdown by Tucker Carlson on Fox News.) I don’t believe he is a vegetarian, much less an animal rights activist. Yet these were his words:

200 years from now… the way we treat animals will rank among our biggest crimes.

And the predictions are bipartisan in nature. Charles Krauthammer, one of the nation’s most prominent conservative columnists, argued near the end of his career that future generations would condemn us for eating animals:

I’m convinced that our great-grandchildren will find it difficult to believe that we actually raised, herded and slaughtered them on an industrial scale — for the eating.

There are countless other examples. The distinguished philosopher Martha Nussbaum has described species membership as a “frontier of justice” and has devoted much of her recent work to defending animal rights. (Back when I was in law school, it was public knowledge that, despite her support for animal rights, Martha was not a vegetarian.) The futurist Yuval Noah Hariri has condemned industrial animal agriculture as “one of the worst crimes in history.” And New York Times’ columnist Ezra Klein has argued that “we will look back on this age of cruelty to animals with horror.”

It is, to me, quite compelling that such a wide range of thinkers believe, at least in principle, in the message of animal rights. But how can we truly know what future generations will believe? How do we ensure our own biases aren’t distorting our judgment?

Princeton’s Anthony Appiah, who has been instrumental to my own thinking on social change¹, once looked at historical periods of great moral failure and came up with a list of three signs that a practice or institution is destined for future condemnation. Two of those three by Appiah — what I call moral asymmetries, and strategic ignorance — are particularly important. But I would add one other sign, pointed out by former mentor Cass Sunstein: widespread preference falsification.

When all three of these signs exists, there is a strong argument that the practice at issue is wrong, despite its contemporary acceptance, and destined for historical condemnation. And all three signs exist very strongly in the space of animal rights.

Let’s start with moral asymmetry. Appiah argues that historical atrocities have been committed when “defenders of the custom tend not to offer moral counterarguments but instead invoke tradition, human nature or necessity.” Slavery is an important example. No one really made an ethical defense of slavery; they simply argued it was necessary to maintain the American system. (In many ways, as Nobel Prize winner Robert Fogel has argued, it was necessary to that system; the system simply needed to change.) The key thing to note about this, however, is that customs that have ethical arguments only on one side are inherently unstable. When a political movement challenges the custom, it cannot provide any moral defense. And because we are inherently moral animals, these sorts of challenges are common in human history. That is precisely what happened with the end of antebellum slavery in the United States. It was felled by a powerful political movement in part because there was no moral defense.

This is certainly true of animal rights. You rarely hear an ethical defense of animal cruelty; instead, defenders invoke tradition, human nature, or necessity. As with slavery, when a political movement finally rises up to challenge violence against animals, we will win because the other side has no moral arguments to fuel its political defense.

Appiah’s second factor is strategic ignorance: “avoiding truths that might force [people] to face the evils in which they're complicit.” This was certainly true of the subjugation of women, and it’s part of the reason that Susan B Anthony was not jailed when she tried to vote. The very judges and attorneys who prosecuted her preferred to ignore her concerns, rather than confront them face to face. They were, in other words, strategically ignorant because they did not want to see themselves, in a democracy, as denying essential freedoms to half the nation. As with moral asymmetry, however, strategic ignorance is not a solid foundation for a custom to withstand scrutiny. If the only way we can justify a tradition is by being ignorant to its impacts, the tradition is almost bound to fall. That was true of denying women the right to vote. Anthony’s trial forced the nation out of strategic ignorance and, within one generation, the movement won the right to vote.

What was true of women’s suffrage in 1873 is true of animal rights today. Most people intentionally choose to avert their eyes when they see animal cruelty. As the famous Paul McCartney saying goes, “If slaughterhouses have glass walls, we’d all be vegetarian.” And who among us, when talking about the violence in factory farms, has not had people respond, “Oh, I’d prefer not to know.” While this is a problem in the short term, it also should give us hope. A tradition grounded in ignorance is not one that will withstand the test of history.

The final factor, from Sunstein’s work, is preference falsification. The concept was coined by social scientists who were trying to understand why social change happens — and often happens much faster than we think. What they found is that episodes of rapid social change often happen shortly after episodes of widespread “closeting” of people’s real moral beliefs. Perhaps the classic example is gay rights. Because of social pressure, even many gay people pretended they were not gay. Many went further, and pretended they were opposed to homosexuality (while living secret lives of homosexuality themselves). Consider the case of Larry Craig, the Republican Senator in Idaho who was caught propositioning men in an airport bathroom:

While preference falsification, in the short term, can make it seem like social change is difficult — after all, if people are afraid to support a movement, how can it succeed? — the existence of widespread preference falsification is an indication that a tradition’s time might be short. After all, if its support is based on a lie, once people realize they can speak their minds openly, its support base will quickly fall apart. That is precisely what happened with gay rights. When it became not just culturally tolerated but celebrated to be gay, the nation changed rapidly. And we now look back at people like Larry Craig with contempt.

Perhaps more than any other social movement in history, preference falsification is a fundamental attribute of the landscape on animal rights. The reason is that, unlike other social movements, animal rights implicates people’s behaviors three times a day. People, who feel the natural desire to fit in, therefore have 3 chances to falsify their preferences every day. Even people who do not want to hurt animals still eat animals.

This helps explain how half of Americans can support banning slaughterhouses and factory farms while less than 5% are vegetarian. It helps explain the massive rate of recidivism in veganism, with perhaps 75% or more of vegans giving it up within a year. And it helps explain why even very influential figures, such as Ezra Klein or Cass Sunstein, are scared to “come out” in support of animal rights. As Ezra put it:

There's nothing I feel as strongly about that I feel as uncomfortable expressing, as this passes judgment on too many people. It indicts too much. I know how to have a conversation about tax policy or health policy but… this? No one wants to hear this you're immediately dismissed as a self-righteous crank a hippie extremist or or if you're like me and if you're new to this… I mean I've got an Instagram feed you can go find pictures of really delicious looking burgers in it. You're a hypocrite

And what's so weird about this conversation what makes it so different than than so many of the ones I have that are actually debate is that no one really disagrees with what you're saying. There isn't really disagreement over whether pigs and cows and chickens feel pain. I don't know people really who defend factory farming.

As with gay rights, however, the problem caused by preference falsification is also an opportunity. If — and this is an important “if: — we can convince enough people to “come out” into the public square and state their true beliefs. Even when it comes at a social cost three times a day.

Until then, those of us who support the movement, closeted or otherwise, can take comfort in this: the plight of animals has all the attributes of a historical atrocity that, someday soon, future generations will condemn.

The footbinding case study from my article comes from one of Appiah’s recent books.

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?