| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The Rules of Social Influence |

| Date | November 2, 2022 6:02 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

Last week, I blogged about two psychological forces [ [link removed] ] that have been crucial to justifying the greatest crimes of history: the banality of evil, and the doctrine of necessity evil. As I wrote, Harvard University's troubling statement, in defense of experiments in which a baby monkey’s eyes were sutured shut, is a demonstration of how these forces operate to normalize and justify conduct that seems abhorrent.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

What I did not describe, however, is how those forces come into effect in the first place. How does evil become “normal”? And how does the public come to see it as “necessary”? While each case involving the banality of evil is in many ways unique – some involve government; others involve corporate greed – there is a single mechanism that is almost always at play when atrocities become normalized. And, surprisingly, it is the same mechanism that has also driven progress for justice. Indeed, the mechanism at issue was one of the primary forces that allowed for the creation of the grassroots animal rights network I founded, Direct Action Everywhere, and the creation of many other movements for justice.

It is also a mechanism that almost all of us deny has any impact on us.

It goes by many names, but I will use the most simple one: the rule of social influence. And only when we understand the rule of social influence – and the way it harnesses the power of ordinary people, connected to each other in a network – can we maximize our impact on the world.

—

Human beings have fundamental disagreements about what influences us. Some say they’re motivated by higher callings, such as ethics or principle. Others will concede to being driven by more base impulses: sex, money, or power. But if there is one thing that virtually every human being agrees with, it is that we are independent of the people around us.

“I think for myself,” we all say to ourselves.

In contrast, almost no one has ever said, “I don’t think for myself. I just follow the crowd.”

But compelling data shows that the crowd affects us all. Two findings are particularly important. The first finding, compiled by Yale scholar Nicholas Christakis, in a study of thousands of residents of the city of Framingham, Massachusetts, found that a wide variety of seemingly unrelated outcomes – from obesity to smoking to even psychological well-being – seemed to spread through social networks like a virus. For example, Christakis found that if a person’s friend became obese, it increased their odds of being obese themselves by 45%, through some combination of direct influence (sharing unhealthy foods) and social norms (normalizing a higher body weight).

What was perhaps most remarkable about this effect, however, was that it was not just limited to a person’s direct social connections. It bounced to “three degrees of separation.” What this means, specifically, is that social influence can bounce from one friend to the next. We are influenced by the friends of our friends. And even the friends of our friend’s friends. Indeed, Christakis found that, while the impact of having an obese friend was to increase your personal risk of obesity by 45%, there was a similar impact if one of your friend’s friends was obese (25%) and even if your friend’s friend’s friend was obese (10%). Christakis gave this phenomenon a name: three degrees of influence. He discusses in a recent TED talk:

Around the same time, however, another prominent sociologist – Duncan Watts of the University of Pennsylvania – made an even more important finding: that human societies are “small world networks.” Watts, who I have had the pleasure of hosting on my podcast [ [link removed] ], was a trained physicist who was studying the synchronized chirping of crickets in the wild when he made a shocking discovery: human social networks involving billions of people synchronize in much the way that a small group of crickets synchronize their songs in a suburban backyard. The reason for this, fundamentally, was an enduring attribute of human social networks. No matter how big human societies get, any two people are separated by at most six degrees of separation.

The reason for this is that, while most people cluster with a small number of local contacts – call them “cliques” – there are many hubs that connect all the various cliques into a wider social network. Consider the network for air travel. While many smaller cities will have a limited number of destinations, because one of those destinations is likely to be a major hub airport, every city on earth is connected by air to every other city in a relatively small number of jumps.

What is true of air travel is also true of human sociality. Even as our population exceeds 8 billion, it is still a “small world” connected by just six jumps.

Christakis’s rule of three degrees of influence becomes even more important in a small world. After all, if every one of us can influence other people within three degrees of influence - and if the entire human species can be reached within six degrees of influence – then we can start understanding how change can happen with a small number of people, and with relative speed. Indeed, the so-called rule of 3.5% [ [link removed] ], a phenomenon whereby an entire society can almost immediately change when a mere 3.5% of the population engages in sustained nonviolent direct action, is driven by these sociological forces. You don’t need that many people, when it’s possible to reach – and influence – the entire human species in a few short jumps! Listen to Chenoweth’s TED talk:

While Christakis and Erica Chenoweth, who coined the rule of 3.5%, were studying mostly positive movements for change, the same rules of social influence show how great evil can happen suddenly, as well. That is precisely what happened in the period of Nazi Germany. A relatively small minority of very committed people set off a chain reaction that led to a historic atrocity. It is also how universities like Harvard have influenced the public, in justifying seemingly barbaric animal experiments. A relatively small set of highly motivated individuals – vivisectors in the biomedical industry – have managed to normalize practices that the vast majority of people would find horrific. It’s turning Margaret Mead’s famous saying on its head.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.” Replace “change the world” with “inflict great violence on the world,” and we have basically described the banality of evil.

For the longest time, I believed that the battle of good vs evil was a battle over these rules of social influence. Those who got the most people to advocate for their cause, in a coordinated and passionate way, would eventually win over the entirety of human society. Indeed, the rule of social influence is the reason I co-founded Direct Action Everywhere. As Watts has stated, masses of densely-connected people, spreading their influence like a wildfire, are the most powerful force for change in human history.

But then I ran into both conceptual and factual roadblocks. Conceptually, the rule of social influence seemed too easy. If any one of us could spread influence that would go, from a network perspective, halfway across the human species, why is change so uncommon? The status quo, and not cascading influence, seems to be the norm of human society. Factually, even after we built seemingly powerful networks of animal rights activists, change seemed to commonly fizzle out. If Christakis was right that social influence was such a powerful force, and Watts was right that influence could easily spread through the entire human species, why were we unable to push forward the agenda of animal rights?

The answer lies in a simple observation about influence: for every attempt at influence, there is a countervailing influence that holds it back. The work of Damon Centola, also at UPenn, has shown through experiments why this happens, and why ordinary people – and not the densely connected “hubs” within human society (e.g., celebrities or politicians) – are key to change.

Let’s take Oprah Winfrey as an example. Many people believe Oprah is among the most influential people in the world. And there is a superficial argument this is the case. Oprah reaches millions of people across the world. She has 43 million followers. And when she, for example, selects a book for her book club, it almost invariably becomes a best seller. This is why activists of various movements are desperate to earn the support of people like Oprah – celebrities, politicians, and other influencers. Winning over Oprah, it might be said, is sort of like gaining control over an airport hub. “If we have the hub, we can direct all the traffic, right?”

Wrong.

And the reason is countervailing influence. You see, Oprah’s influence on her audience is not one-way. Her audience also influences – and constrains – her. Oprah’s book club selections [ [link removed] ], for example, are all very similar: stories of triumph over trauma, filled with dollops of self help. If she chose a Spiderman comic book, or a horror novel like Stephen King, her audience would revolt. Her massive number of connections will hold her back from pushing for significant change.

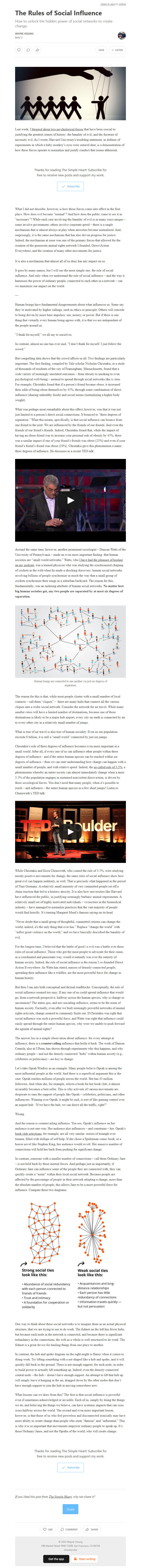

In contrast, someone with a smaller number of connections – call them Ordinary Jane – is not held back by these inertial forces. And perhaps just as importantly, if Ordinary Jane can influence some of the people they are connected with, they can quickly create a “norm” within their local social network. Because people are affected by the percentage of people in their network adopting a change, more than the absolute number of people, this allows Jane to be a more powerful force for influence. Compare these two diagrams:

One way to think about these social networks is to imagine them as an actual physical structure, that we are trying to use to do work. The fishnet on the left has fewer hubs, but because each node in the network is connected, and because there is significant redundancy in the connections, the web as a whole is well structured to do work. The fishnet is a great device for hauling things from one place to another.

In contrast, the hub and spoke diagram on the right might is flimsy when it comes to doing work. Try lifting something with a net shaped like a hub and spoke, and it will quickly fall back to the ground. There is not enough support, for each node, in order to build power to actually lift something up. Indeed, even the densely connected central node – the hub – doesn’t have enough support. An attempt to lift that hub up will simply leave it hanging in the air, dragged down by the other nodes that don’t have enough support to join the hub in moving somewhere new.

What lessons can we draw from this? The first is that social influence is powerful even if sometimes acknowledged or invisible. Each of us, simply by doing the things we do, and believing the things we believe, can have systemic impacts that can criss cross halfway across the world. The second and even more important lesson, however, is that those of us who feel powerless and disconnected ironically may have more ability to create change than people who seem “famous” and “influential.” This is why it is so important that movements empower ordinary people to speak up. It’s those Ordinary Janes, and not the Oprahs of the world, who will create change.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Last week, I blogged about two psychological forces [ [link removed] ] that have been crucial to justifying the greatest crimes of history: the banality of evil, and the doctrine of necessity evil. As I wrote, Harvard University's troubling statement, in defense of experiments in which a baby monkey’s eyes were sutured shut, is a demonstration of how these forces operate to normalize and justify conduct that seems abhorrent.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

What I did not describe, however, is how those forces come into effect in the first place. How does evil become “normal”? And how does the public come to see it as “necessary”? While each case involving the banality of evil is in many ways unique – some involve government; others involve corporate greed – there is a single mechanism that is almost always at play when atrocities become normalized. And, surprisingly, it is the same mechanism that has also driven progress for justice. Indeed, the mechanism at issue was one of the primary forces that allowed for the creation of the grassroots animal rights network I founded, Direct Action Everywhere, and the creation of many other movements for justice.

It is also a mechanism that almost all of us deny has any impact on us.

It goes by many names, but I will use the most simple one: the rule of social influence. And only when we understand the rule of social influence – and the way it harnesses the power of ordinary people, connected to each other in a network – can we maximize our impact on the world.

—

Human beings have fundamental disagreements about what influences us. Some say they’re motivated by higher callings, such as ethics or principle. Others will concede to being driven by more base impulses: sex, money, or power. But if there is one thing that virtually every human being agrees with, it is that we are independent of the people around us.

“I think for myself,” we all say to ourselves.

In contrast, almost no one has ever said, “I don’t think for myself. I just follow the crowd.”

But compelling data shows that the crowd affects us all. Two findings are particularly important. The first finding, compiled by Yale scholar Nicholas Christakis, in a study of thousands of residents of the city of Framingham, Massachusetts, found that a wide variety of seemingly unrelated outcomes – from obesity to smoking to even psychological well-being – seemed to spread through social networks like a virus. For example, Christakis found that if a person’s friend became obese, it increased their odds of being obese themselves by 45%, through some combination of direct influence (sharing unhealthy foods) and social norms (normalizing a higher body weight).

What was perhaps most remarkable about this effect, however, was that it was not just limited to a person’s direct social connections. It bounced to “three degrees of separation.” What this means, specifically, is that social influence can bounce from one friend to the next. We are influenced by the friends of our friends. And even the friends of our friend’s friends. Indeed, Christakis found that, while the impact of having an obese friend was to increase your personal risk of obesity by 45%, there was a similar impact if one of your friend’s friends was obese (25%) and even if your friend’s friend’s friend was obese (10%). Christakis gave this phenomenon a name: three degrees of influence. He discusses in a recent TED talk:

Around the same time, however, another prominent sociologist – Duncan Watts of the University of Pennsylvania – made an even more important finding: that human societies are “small world networks.” Watts, who I have had the pleasure of hosting on my podcast [ [link removed] ], was a trained physicist who was studying the synchronized chirping of crickets in the wild when he made a shocking discovery: human social networks involving billions of people synchronize in much the way that a small group of crickets synchronize their songs in a suburban backyard. The reason for this, fundamentally, was an enduring attribute of human social networks. No matter how big human societies get, any two people are separated by at most six degrees of separation.

The reason for this is that, while most people cluster with a small number of local contacts – call them “cliques” – there are many hubs that connect all the various cliques into a wider social network. Consider the network for air travel. While many smaller cities will have a limited number of destinations, because one of those destinations is likely to be a major hub airport, every city on earth is connected by air to every other city in a relatively small number of jumps.

What is true of air travel is also true of human sociality. Even as our population exceeds 8 billion, it is still a “small world” connected by just six jumps.

Christakis’s rule of three degrees of influence becomes even more important in a small world. After all, if every one of us can influence other people within three degrees of influence - and if the entire human species can be reached within six degrees of influence – then we can start understanding how change can happen with a small number of people, and with relative speed. Indeed, the so-called rule of 3.5% [ [link removed] ], a phenomenon whereby an entire society can almost immediately change when a mere 3.5% of the population engages in sustained nonviolent direct action, is driven by these sociological forces. You don’t need that many people, when it’s possible to reach – and influence – the entire human species in a few short jumps! Listen to Chenoweth’s TED talk:

While Christakis and Erica Chenoweth, who coined the rule of 3.5%, were studying mostly positive movements for change, the same rules of social influence show how great evil can happen suddenly, as well. That is precisely what happened in the period of Nazi Germany. A relatively small minority of very committed people set off a chain reaction that led to a historic atrocity. It is also how universities like Harvard have influenced the public, in justifying seemingly barbaric animal experiments. A relatively small set of highly motivated individuals – vivisectors in the biomedical industry – have managed to normalize practices that the vast majority of people would find horrific. It’s turning Margaret Mead’s famous saying on its head.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.” Replace “change the world” with “inflict great violence on the world,” and we have basically described the banality of evil.

For the longest time, I believed that the battle of good vs evil was a battle over these rules of social influence. Those who got the most people to advocate for their cause, in a coordinated and passionate way, would eventually win over the entirety of human society. Indeed, the rule of social influence is the reason I co-founded Direct Action Everywhere. As Watts has stated, masses of densely-connected people, spreading their influence like a wildfire, are the most powerful force for change in human history.

But then I ran into both conceptual and factual roadblocks. Conceptually, the rule of social influence seemed too easy. If any one of us could spread influence that would go, from a network perspective, halfway across the human species, why is change so uncommon? The status quo, and not cascading influence, seems to be the norm of human society. Factually, even after we built seemingly powerful networks of animal rights activists, change seemed to commonly fizzle out. If Christakis was right that social influence was such a powerful force, and Watts was right that influence could easily spread through the entire human species, why were we unable to push forward the agenda of animal rights?

The answer lies in a simple observation about influence: for every attempt at influence, there is a countervailing influence that holds it back. The work of Damon Centola, also at UPenn, has shown through experiments why this happens, and why ordinary people – and not the densely connected “hubs” within human society (e.g., celebrities or politicians) – are key to change.

Let’s take Oprah Winfrey as an example. Many people believe Oprah is among the most influential people in the world. And there is a superficial argument this is the case. Oprah reaches millions of people across the world. She has 43 million followers. And when she, for example, selects a book for her book club, it almost invariably becomes a best seller. This is why activists of various movements are desperate to earn the support of people like Oprah – celebrities, politicians, and other influencers. Winning over Oprah, it might be said, is sort of like gaining control over an airport hub. “If we have the hub, we can direct all the traffic, right?”

Wrong.

And the reason is countervailing influence. You see, Oprah’s influence on her audience is not one-way. Her audience also influences – and constrains – her. Oprah’s book club selections [ [link removed] ], for example, are all very similar: stories of triumph over trauma, filled with dollops of self help. If she chose a Spiderman comic book, or a horror novel like Stephen King, her audience would revolt. Her massive number of connections will hold her back from pushing for significant change.

In contrast, someone with a smaller number of connections – call them Ordinary Jane – is not held back by these inertial forces. And perhaps just as importantly, if Ordinary Jane can influence some of the people they are connected with, they can quickly create a “norm” within their local social network. Because people are affected by the percentage of people in their network adopting a change, more than the absolute number of people, this allows Jane to be a more powerful force for influence. Compare these two diagrams:

One way to think about these social networks is to imagine them as an actual physical structure, that we are trying to use to do work. The fishnet on the left has fewer hubs, but because each node in the network is connected, and because there is significant redundancy in the connections, the web as a whole is well structured to do work. The fishnet is a great device for hauling things from one place to another.

In contrast, the hub and spoke diagram on the right might is flimsy when it comes to doing work. Try lifting something with a net shaped like a hub and spoke, and it will quickly fall back to the ground. There is not enough support, for each node, in order to build power to actually lift something up. Indeed, even the densely connected central node – the hub – doesn’t have enough support. An attempt to lift that hub up will simply leave it hanging in the air, dragged down by the other nodes that don’t have enough support to join the hub in moving somewhere new.

What lessons can we draw from this? The first is that social influence is powerful even if sometimes acknowledged or invisible. Each of us, simply by doing the things we do, and believing the things we believe, can have systemic impacts that can criss cross halfway across the world. The second and even more important lesson, however, is that those of us who feel powerless and disconnected ironically may have more ability to create change than people who seem “famous” and “influential.” This is why it is so important that movements empower ordinary people to speak up. It’s those Ordinary Janes, and not the Oprahs of the world, who will create change.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a