|

How Harvard Justifies Animal Torture with the Doctrine of “Necessary Evil”

A laboratory experiment shows how evil can be rationalized – and challenged with compassion.

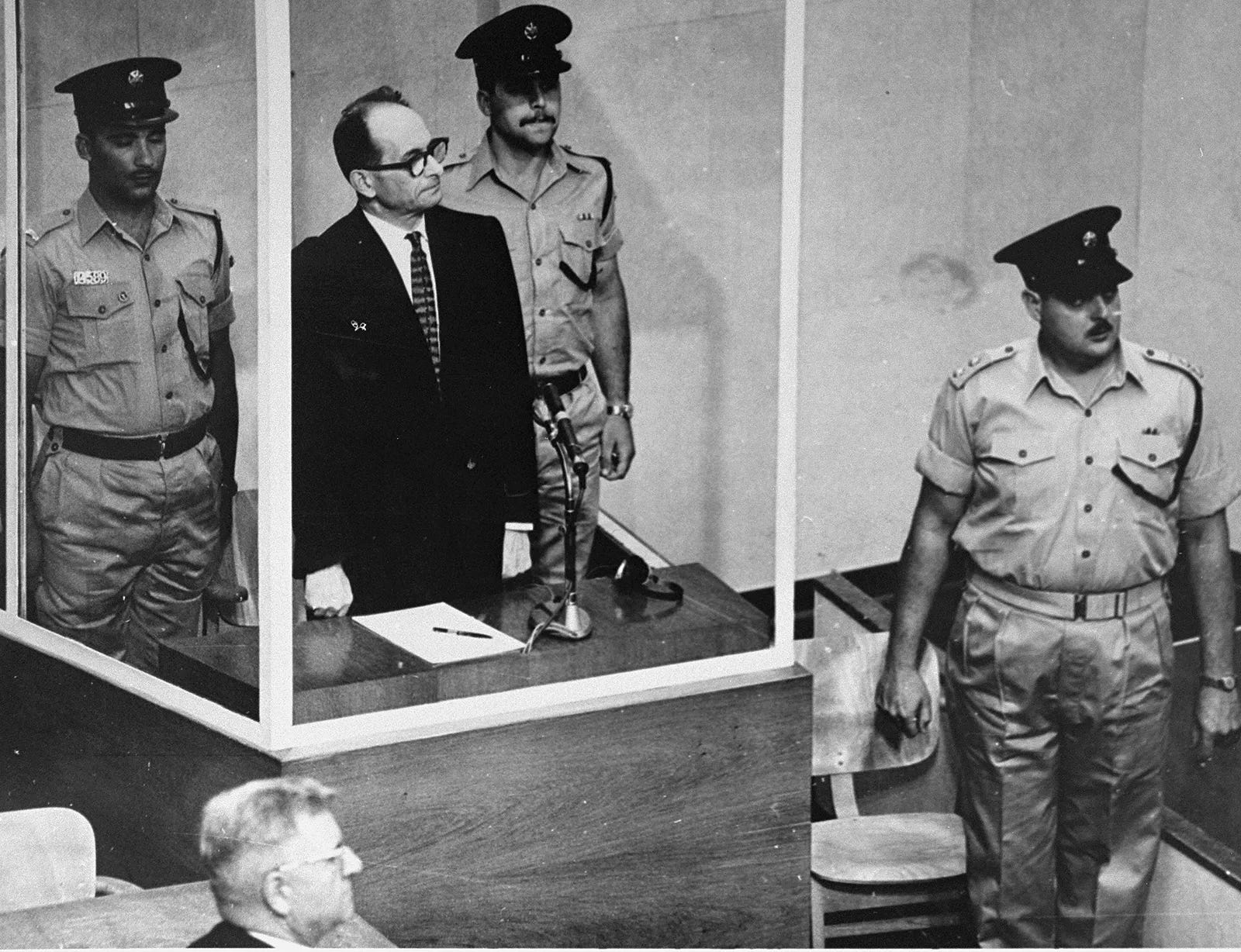

The philosopher Hannah Arendt, in her groundbreaking book Eichmann in Jerusalem, coined what is among the most fundamental concepts for those who seek to understand the great injustices of history: the banality of evil.

In observing the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the primary Nazi leaders responsible for the Holocaust, Arendt noted that Eichmann was a shockingly ordinary person, with seemingly no hatred for Jews or other victims of the Holocaust. He was, rather, motivated by the sorts of routine and bureaucratic desires that most of us are motivated by: the desire to fit in; the aspiration for professional advancement; and the belief that he needed to “follow the rules.”

When the people around Eichmann started believing in the mass extermination of Jews, and it became part of his job to join them, Eichmann enthusiastically participated for the same reason that you or I might join a new policy at work. “I was one of the many horses pulling the wagon and couldn't escape left or right because of the will of the driver,” Eichmann wrote in his diary. Eichmann’s campaign of mass murder, in other words, was shockingly “banal,” i.e., so normal that it didn’t seem like an issue at all – much less one of the greatest crimes in history.

Perhaps the most important implication of Arendt’s concept is that those who are fighting evil are not, primarily, challenging malice or hate. They are challenging the idea that evil is normal. But there is a sister concept to the banality of evil that may be just as important to rationalizing evil: the concept of “necessary evil.” Part of how a disturbing practice becomes “banal” is that it is rationalized as “necessary.”

For Eichmann, mass murder became necessary for a whole host of reasons, both personal and political. On an individual level, complying with his orders, even as a high-level officer in the German army, was “necessary” to his professional standing and advancement. On the political level, removing the threat posed by Jews was “necessary” to protecting the safety of Germans. This included murdering children. As historian Lawrence Rees has written:

The reason [the Nazis] felt justified in their acts – and Himmler explicitly said this in a speech in 1943 – was that if you just killed the adults, the children would grow up to be avengers and they would come after your own children. So if you really loved your children then you should kill their children. If you were brave enough, you would have solved the problem for all time.

Think about this bizarre twist in logic. “So if you really loved your children then you should kill their children.” Evil harnesses one of the best things about us (our compassion and love for children) to bring out the worst in us (violence against other children). It leaves out the massive factual and ethical leaps one must make to arrive at the suggested conclusion. Factually, how does killing other children really save our own? Ethically, how can we possibly justify killing children even if our goal is to save other children?

I’ve been thinking about these twin concepts – the banality of evil, and the necessity of evil – over the last month because they have been one of the prosecution’s most important talking points in attempting to imprison us for challenging the systemic abuse of animals in factory farms. Smithfield argued repeatedly through trial that its practices were part of a normal part of food production – and that those who were trying to challenge them were part of an “anti-meat” movement determined to undermine Americans’ need to obtain food. The abuses we exposed – including starving piglets nursing on their mothers’ mutilated reproductive organs – were actually normal and necessary.

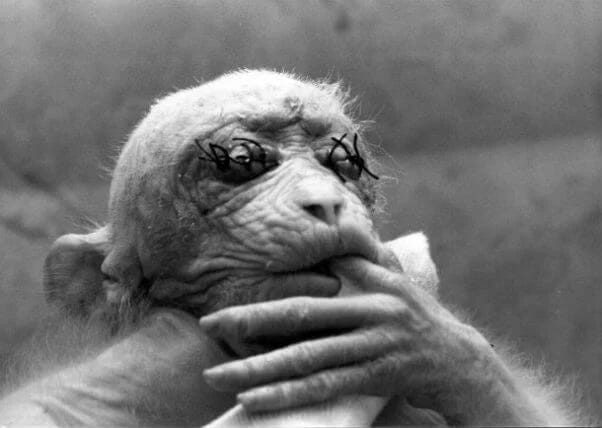

But these concepts have also come up in the context of a recent exposé by PETA showing that a researcher at Harvard Medical School, Margaret Livingstone, has performed disturbing experiments on animals, including suturing the eyes of baby monkeys shut. (Yes, you are reading that correctly.) That particular technique, which was made infamous by an ALF raid of a laboratory in California in 1985, was seemingly abandoned by vivisectors after it was exposed decades ago. But nearly 40 years later, PETA revealed in recent days that it continues. Be forewarned, the footage in this video is disturbing.

What is even more disturbing about this case, however, is not just the nature of the abuse but Harvard Medical School’s response:

Harvard Medical School is deeply concerned about the personal attacks directed at scientists who conduct critically important research for the benefit of humanity.

The content presented on the PETA website is misleading and contains factual inaccuracies. The video, certain photos, and some of the behaviors described on the website are not from Dr. Margaret Livingstone’s lab, and descriptions related to her methods contain inaccuracies and exaggerations.

Research led by Dr. Livingstone continues to provide critical knowledge about vision, visual disorders, brain development and neurological disorders. Insights from Dr. Livingstone’s research in macaques have been instrumental in developing a clinical treatment for tremor, as well as for therapies for Alzheimer’s disease and a lethal brain cancer called glioblastoma that are now under clinical investigation…

As with all animal research conducted at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Livingstone rigorously follows applicable federal, state, and institutional policies and regulations that ensure the humane and safe care of and use of animals, including the Animal Welfare Act in accordance with USDA regulations and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Animals. In addition, Harvard Medical School is accredited by AAALAC International, a voluntary peer-review accreditation program, in which research programs must demonstrate they meet the standards required by law, and are going the extra step to achieve excellence in animal care and use.

There are a few things I want to note about the statement. The first is that it focuses almost entirely on the fact that Harvard’s practices were normal and “following the rules.” It does not even acknowledge any of the facts of the experiments or the apparent suffering caused to a sentient being by suturing her eyes shut. Rather, Harvard simply tries to make the practice seem routine and acceptable by making a false appeal to authority – the approval of the USDA and an accreditation organization called AALAC. This is the banality of evil at work. “We don’t have to defend what we are doing because it’s normal and bureaucratically approved.”

(Left unsaid is that the regulatory bodies and accreditation programs at issue are in bed with the vivisection industry. Even a former high level veterinarian at the USDA, for example, has stated that he had no power to effectively challenge industry abuses, and AAALAC is widely understood to be a rubber stamp for the industry and accredited a laboratory that was just shut down by the government for criminal cruelty to dogs.)

The second thing to note is that Harvard makes the evil at issue seem necessary, by suggesting that the torture of baby monkeys is necessary to save human lives. The example that caught my eye, in particular, was Harvard’s argument that Livingstone’s research has been “instrumental in developing… therapies for Alzheimer’s disease and a lethal brain cancer called glioblastoma that are now under clinical investigation.” To oppose this research, in short, would not just be to oppose a “normal” practice but to oppose something “necessary” to saving human life. Livingstone notes in a personal statement that her own mother died of glioblastoma.

Recall what we previously discussed about the fallacy of necessary evil, and how it harnesses the best in us – our compassion – to induce us to support what’s worst in us. That is exactly what is happening in Harvard’s statement. “If you love your mom, you have to torture and kill these other mothers and their babies.” But, as before, there are factual and ethical leaps that are left unstated. Factually, how exactly does suturing a baby monkey’s eyes shut help save patients of brain cancer? Livingstone cites some speculative therapies for cancer, and states summarily (with citation to no evidence or data) that those therapies would not have been discovered without the torture of monkeys. But this falls short of the extraordinarily high burden of proof we usually require to justify violence against other living beings. For example, Livingstone’s own statement, to justify the factual necessity of torturing monkeys, does not cite a single study – peer-reviewed or otherwise – but rather only links bizarrely to a report involving the blood-brain barrier in… mice.

Ethically, Livingstone and Harvard fail to engage at all with the question of whether violence of this sort can be justified, even if it did have some benefits for human beings. This gap is particularly relevant to me and my family. You see, Livingstone is not the only person with a mother who died of glioblastoma. My mother died of glioblastoma in 2015, in one of the most difficult experiences of my life. And her suffering was terrible. She lost the ability to talk, to walk, and eventually, even to stand. But, unlike Harvard, I do not assume my mother would have wanted other living beings to be tortured to engage in some speculative treatment to save her life. Far from it, I know the opposite is true. My mother would have hated the idea that anyone suffered to save her, including her own children. Because she knew that the best thing about us, as a species, and the best thing about her as a mother, was compassion.

In her last few months in life, DxE released its first open rescue – the conclusion of a decade-long journey for me. And when I showed my mom the images of a miserable, huddling bird – so worn down and defeated that it appeared she had given up on life – my mom started to cry.

“What can we do to help them?” she asked me, while wiping away tears. “What can we do to help these poor little ones?”

|

She responded this way because she understood, very vividly, how it felt to be assaulted by disorder and disease. And she never wanted anyone to go through anything similar. To the contrary, she wanted, even on her deathbed, to help those who suffer.

The bravery of her choice, however, is not unique. And what is most disturbing about Harvard’s statement is not just that it makes the cruel choice to torture animals seem factually and ethically necessary but that it takes an impoverished view of who we are as human beings. Harvard’s statement denies that people like my mom exist. People who can look beyond their own self interest and see the suffering in another being’s eyes. People who can see the brutal mistreatment of other living beings – human or non-human – as something other than normal and necessary. People with compassion. But I know, from my own personal experience, that people like this don’t just exist; as the jury verdict in Utah this month shows, compassionate people are everywhere.

My mom taught me this lesson, seven years ago when she cried tears for a suffering bird, just months before she herself passed away. I hope Harvard and Livingstone learn this lesson, someday, too.

–

The case of cruel experiments at Harvard is particularly important to me because my next big trial – yes, I have another one (in fact, another two) – will involve cruel experiments on animals. In April 2017, I led an investigation and open rescue at Ridglan Farms, one of the largest beagle breeding and research facilities in the world. Many of the experiments performed on Ridglan dogs had nothing to do with human health and life. In perhaps the most notorious example, Ridglan sent beagles to a lab where they were force-fed laundry detergent until they vomited blood and died. And the prevailing conditions the dogs were raised in – typically, solitary wire cages that were only slightly larger than the dogs themselves – induced severe physical and psychological damage. Julie, for example, was so tormented by her living conditions that, 6 years later, she still engages in disturbing repetitive behavior – e.g., spinning constantly to her right. The video speaks for itself:

This is not science. It’s violence.

Yet the company and industry, like the Harvard researchers, have insisted that this torture was normal and necessary. By now, hopefully you’re able to diagnose the rationalization process at work. I’ll write on a future occasion, more specifically, about techniques to challenge the doctrine of necessary evil. One key element is to turn the tables on the doctrine, by normalizing opposition to the abuse (rather than support for it), and by making the act of rescue (rather than the act of animal torture) necessary. But for now, I’ll say this. By far the most important thing to challenge evil is, well, to overcome complacency (both our society’s, and our own) with compassion. The banality and necessity of evil are insidious and powerful forces. But, as with my mom, they can be defeated with compassion.

Thank you for being part of that struggle. Julie and I appreciate it.

—

Some other updates

There are some big changes afoot, with this blog and the accompanying podcast and organization. In particular, in light of my unexpected acquittal, we are probably going to shift everything to the same theme: The Simple Heart. And we are going to change up the podcast by trying to include folks who are part of the animal rights community in the conversation. This week, I’ll be recording a conversation with Priya, Dean, and Chloe on how the most important influencer is… you. Here’s the event page; you can also join via Zoom by shooting me an email or commenting on the blog. Next week, I’ll be speaking to my friends Eric and Matthew on some of the very moral issues discussed in today’s blog: when can “evil” be justified, if at all?

That also means the podcast schedule will change. The usual podcast that has typically been released on Tuesdays will now be released on Thursday. And we’ll do a short podcast, a recording of the conversation at Friday Night Hangouts, on Mondays. We’re aiming to release both of these at 12 pm PT.

I am also getting back to blogging once a week on a topic you choose, so please take one minute to fill out this survey. Among the possibilities this week include, “What Everyone Can Learn from the Man Who Tortured Cats” and “Why the Media (Usually) Ignores Animal Rights.” I want to particularly ask you to submit questions or comments. I’ll try to elevate a key question or comment from the blog, attributing it to you.

That’s all for today. Thanks for reading!

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?