|

On October 8, 2022, a jury in southern Utah acquitted me and co-defendant Paul Darwin Picklesimer of all charges in relation to an open rescue at the largest pig farm in the nation, Smithfield’s Circle Four Farms. The victory for the right to rescue was unprecedented. In the history of open rescue, from its beginnings with Patty Mark in Australia (and Gene Baur and Lauri Houston, in the United States) to the present day, I’m not aware of a single case where defendants have been acquitted. And there has been much speculation as to what caused this remarkable result.

Many have applauded our legal team and strategy. Indeed, both Mary Corporon and Elizabeth Hunt (who represented me up until the point of trial, when she gracefully stepped back and allowed me to take over as counsel for myself) did a fabulous job. Others point to change of venue, triggered by death threats against animal rights activists, as crucial to our victory. And, again, it’s likely that the move out of Beaver County – where 1 in 4 workers are employed by Smithfield – played a key role in the outcome. (Huge shout out to Curtis Vollmar and his team for doing the outreach in Beaver County that exposed the violent repression of the local sheriff’s office.) One can finally point to movement unity. The tide of diverse voices defending the right to rescue did not just lift my spirits when I was feeling broken. It amplified the story of the trial to millions across the world, and perhaps convinced the judge, finally, to give us some limited due process, e.g., admitting evidence as to the value of the two piglets at issue.

There were, however, three other important factors that were crucial to this win that have not been widely discussed. Indeed, we kept these factors highly confidential. Even in the first few days of trial, one of my greatest fears was that these secrets would get out. But now that the trial is done, it’s time to start speaking of them openly – not just so you can have the full story of the Smithfield trial but because these three factors are important for all of our efforts at social change. And the conversation begins with something you’ve heard me say before.

Do your homework. One of the crucial advantages we had over the prosecution in this case is our deep knowledge of factory farms. The prosecution spend enormous time and resources on various legal maneuvers, from excluding evidence to raiding sanctuaries, that they believed would either intimidate us into a plea bargain or fatally weaken our case at trial. They spent much less time understanding, in a detailed fashion, the small details of the case.

The biggest example of this was the prosecution's apparent misunderstanding of the distinctions between gestation and farrowing crates. Count 1 of the charges against us was felony burglary, for entering a building with the intent to remove piglets from a gestation crate building. Yet gestation crates, unlike farrowing crates, have no piglets in them. They are used only for gestating mother pigs. Days before the piglets are born, the mothers are moved to a farrowing shed. Indeed, the state’s own witness, Thayne Young, collapsed under cross examination and conceded that no one could possibly intend to find a piglet in a gestation crate. With no evidence that any piglets were expected (or actually removed) in a gestation shed, the judge was forced to dismiss Count 1 at the end of the trial.

Video footage we attempted to introduce at trial showed that we were shocked to see dead and dying piglets in the gestation barn.

This had two other effects on the case, however. First, it undermined the state’s credibility with both the judge and jury. I could tell, from the looks of confusion on the jury’s faces, and the look of incredulity on the judge’s, that the trial was shifting in our favor when the gestation crate issued was raised on Day 5 of the trial. Second, the gestation crate issue provided a basis for us to introduce evidence of animal cruelty that might otherwise have been disallowed. After all, if the state was alleging we removed piglets from a gestation crate barn, surely we must have the right to present evidence as to what we actually did in a gestation barn, i.e., document abuse rather than rescue piglets. While the judge did not ultimately grant our request to include this evidence – the legal term for this is a “proffer” – the argument around the gestation crate issue, and allowable evidence, in my view played a key role in the decision by the judge to strike all the state’s witnesses no Day 5. The judge, having already ruled that we could not present any evidence of animal cruelty, even when it was crucial to an element of the case, could hardly turn around and allow Smithfield to introduce evidence of their supposed high standards of animal care.

The gestation/farrowing distinction, however, was only one of many nuances that the prosecution failed to grasp because they simply didn’t do their homework. For example, they failed to charge “party liability” against Paul, which would have allowed them to hold Paul liable for my deeds (rather than just his own actions). If they had carefully looked through the footage and photos, they could have easily seen that Paul was a cameraperson, and never carried a piglet out of a barn. But if they had chosen to charge party liability, Paul still could have been found guilty, as an accomplice to the crime. But they simply failed to recognize this key factual issue in the Amended Information that was filed on December 18, 2020.

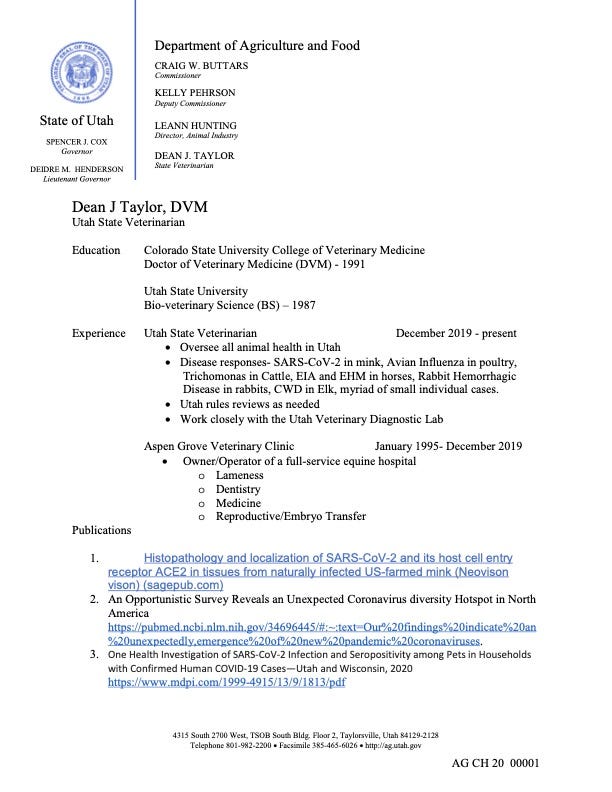

The state also failed to do their homework in researching, and prepping, their witnesses. They retained Dean Taylor, the state vet of Utah, as an expert on the condition of the piglets in this case. But the resume they sent us, while impressive, focused almost entirely on work Dr. Taylor had done with horses, not pigs. Worse yet, when I cross examined Dr. Taylor and asked him if his opinion was less credible than a veterinarian who worked with pigs every day, Taylor answered yes. He failed to realize that he was falling into our trap; the vet we called, Dr. Sherstin Rosenberg, was planning to testify that she treated pigs every day. The state’s own witness, in short, conceded that the defense’s case was the better one.

I could go on and on with various other instances where the state failed to do its homework. But the bigger lesson is, to me, clear. Those who dive deep into the details are those who can create change. Our legal team reviewed (on multiple occasions) every minute of video footage shot at Circle Four. We prepared every witness extensively, with not just mock examination but video recordings that both our legal team and our witnesses could watch to provide feedback. In short, we did our homework. And it showed at trial.

The second factor is that we sought feedback, including from people very different from ourselves. The most notable example of this was a mock trial we performed, with hundreds of “mock jurors” recruited from online surveying systems, to assess the strengths and weaknesses of our case. This study, which was limited to conservative and rural respondents, was the first sign to me that we had a real shot at winning at trial. Approximately one half of respondents were choosing to acquit!

The factors cited by these jurors, in turn, were important to fashioning our legal strategy. For example, post-trial surveys of these mock jurors found that those who acquitted were highly motivated by the fact that we took nothing of value from the pig farm, but were merely trying to give aid to dying animals. (Remarkably, this proved true even when the jury received no instruction that value was a necessary element of burglary or theft.) Those who convicted, in contrast, felt there needed to be some punishment for our night-time entry into someone else’s property.

Accordingly, based on this feedback, our legal strategy focused much of our time on: (1) proving that the piglets had no commercial value, and (2) showing jurors that a not guilty verdict would not suddenly give license to people to break into others’ property, with no accountability. Dr. Rosenberg’s testimony proved crucial with regard to this first factor. My and Mary’s closing statements were both crucial to the second. The net result is that we did better than 50%. We got every one of the jurors to acquit!

The mock trial study, however, was just one example of the extensive feedback we received from lawyers, laypeople, Mormons, omnivores, and a whole host of people who were outside of our bubble. In contrast, the prosecution seemed satisfied to stay within the far-right, pro-corporate circles that dominate Republican politics today. That undermined their ability to reach a (relatively) diverse jury in Washington County.

What is true of this trial is true of efforts to create change, or persuade, more generally. The psychologist Adam Grant discusses the evidence behind a feedback mentality in two recent books: Originals, and Think Again. Whether you are trying to become a master comedian or a spectacular singer, it turns out that great performance is only possible with massive volumes of feedback. We sought that feedback, and it’s one of the reasons we won.

The final factor was a simple story. When we did our homework, we accumulated a massive number of storylines that could have been used at trial. Free speech. Corruption. Government overreach. Etc. But the most powerful stories, and efforts to persuade, focus on a much more simple story.

The so-called identifiable victim effect is one example of how simplicity rules. People are more inclined to offer help when they are told the story of one victim, rather than many. The reason is that it’s hard for the human mind to empathize with a cluster. One can’t imagine what it’s like to be a group, a flock, or herd. But when we look into one animals’ fearful eyes, we immediately understand. We want the animal to be saved.

Lily was one of the stars of the trial, though she appeared only by video.

In this regard, it was perhaps a blessing in disguise that the judge did not allow us to introduce evidence of animal cruelty. While the gory conditions of the farm would have set out clearly to the jury that there were serious problems at the farm, it may have also reduced their ability to empathize with any one of the many individuals who were suffering. In contrast, when my closing arugment focused on a single piglet – “If you make the right choice… maybe, just maybe, a baby pig like Lily won’t have to starve to death on the floor of a factory farm” – it moved the jury.

More generally, while the trial moved in many different directions, and was disrupted by the prosecution’s constant objections, we tried to always make the central moral of the story clear. Rescuing a sick and dying animal is not a crime. And when even Rick Pitman, the turkey farmer we called to testify, repeated this simple story, we started believing we had a chance to win.

The lesson for all of us is that, even as we dive deep into the details, we need to find the simple story that will resonate with our audience. The details we find should paint this story naturally. It should come to us, from the complexity of the case, like a completed jigsaw puzzle emerging from a chaotic pile of pieces. Like a jigsaw puzzle, it takes effort to find that story. But when it emerges, it should be as clear as day.

–

On a certain level, I’m surprised that these factors played such a big role in our case. Doing your homework, getting feedback, and finding the simple story feel like things I’ve heard (and said) before. But in a world where attention spans are low, disagreement and feedback are feared, and storytelling has been replaced by titillation or conflict, very few are actually using this advice.

This is true of animal advocacy. I remember many years ago, when I was starting DxE, and we began publishing blogs and research summaries of the things we were uncovering about social change. A one-time critic of our work, who was reviewing our research, commented something along these lines: “I have no idea if what they’re saying is true, but it seems like they’re the only ones diving into the research. Someone else should probably check their work.” I waited, happily, for someone else to do that; I was excited about the prospect of either verification (which would give me greater confidence that our theory was correct) or disagreement (which would help us improve it). But neither happened. People, with some limited exception, mostly just kept arguing based on intuition and feeling. It was a lost opportunity for the animal rights movement to make progress.

What’s true of the movement is true of you, and of the world. It’s easy to take shortcuts, rather than diving into the details. It’s comfortable to avoid asking others – especially those who are different from you, or even hostile – what they think of our work. And it’s common for us to use a shotgun approach to persuasion, rather than finding the simple story that ties everything together. But none of these approaches actually works. If you want to create change – and perhaps even shock the world, as we did with the Smithfield trial – we’ll have to do the opposite of all these things.

Do your homework. Seek feedback. And find the simple story. Those are the secrets of the Smithfield trial.

—

A few updates:

We may be rebranding the podcast and the new organization’s name around The Simple Heart. The reason is twofold: first, the podcast name change was largely motivated by my anticipated incarceration. The name, Everybody Wayne Hsiung Tonight, feels less interesting and funny if I’m still on the outside. Second, converging around the same name – for the podcast, the blog, and the organization – will allow us to pull everything together, and tell a simple story as to what we’re trying to do with each.

Tonight’s Friday Night Hangout will be my first in a month! Here is the event page. It starts at 7 pm with food and fun. Then we’ll have a 30 minute conversation, starting at 7:30. With respect to the latter part, feel free to join by Zoom. Chloe will give you the link if you respond to this email, or comment below on our website.

If I don’t see you tonight, I hope to see you tomorrow, at the DxE Celebration Party for the Smithfield Trial. Here’s the event page. Paul and I will both be there, and will share some stories about what unfolded at trial, in addition to taking your questions.

I want to get back to surveying you, the readership, on what topics you’d like me to write about. The last few months have been almost entirely focused on the Smithfield Trial. And I will still have lots of legal blogs to write; two more trials are on the horizon. But I also want to ensure this blog has practical value for you. And eventually, give you a chance to participate in our content creation process – by featuring comments, questions, even entire articles from the readers of this newsletter.

Here’s one example, from Taj Uppal, a member of our legal team, who has written one of the most compelling and hilarious accounts of the Smithfield Trial. An excerpt:

I told him I was here to start law school, and he was like “That’s awesome, I’m a lawyer myself!” I already knew that too, but I had to keep my cool so I was like “Woah really?” We started talking and honestly my first impression was that this is one goofy ass mf. He was super high energy, talking to me through mouthfuls of tofu, and telling me stories like this:

“I love talking to animals! I was on my way to the meetup this morning and I saw a squirrel and was like ‘Hi there Mr. Squirrel! How’s it hanging?’ I suppose I shouldn’t assume the squirrel’s gender though…

Keep reading, because it just gets better from there.

Stay tuned for more community meetups, including events for Asians, Effective Altruists, and Lawyers for Animals! Now that I’m back in the Bay, and not in prison, I want to refocus my attention on the thing that is going to bring the most power and meaning to the movement for kindness. Community organizing! And I hope you’ll play a part!

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?