| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | What matters in leadership? (Podcast) |

| Date | September 14, 2022 5:46 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

In July 2017, I faced one of the most difficult leadership challenges of my life. We had just released a ground-breaking investigation [ [link removed] ] of Smithfield Foods, a look inside the largest pig farm in the nation. But before we had time to celebrate – or prepare our legal defense [ [link removed] ] to the charges that would eventually be filed – a group of 43 animal rights activists accused DxE leadership [ [link removed] ], in a letter entitled Steps to Healing, of “patterns of abuse.” The alleged abuse included character assassination, concentrations of power, and allowing a “confessed sexual abuser” to remain in a position of leadership.

The letter itself, however, was not the difficult challenge. Members of DxE, after we provided transparency about the conflicts at issue [ [link removed] ], overwhelmingly supported our leadership team. (Indeed, the primary author of the letter later disavowed it and wrote [ [link removed] ] that it was “a tragic story about a bunch of largely unrelated interpersonal conflicts that got wildly out of hand.”) What was most difficult was the question of what to do with the handful of signatories who had caused the largest problems for our organizing.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Listen to the conversation between Almira Tanner, lead organizer of Direct Action Everywhere, on how leadership can handle crisis. [ [link removed] ]

The problem-causing individuals included a former steering committee member who had become so bitter and accusatory that meetings with him had devolved into shouting matches; the leader of a chapter who had cursed out and insulted other members on group mailing lists; and a woman who claimed to be a victim of rape by a fellow DxE activist (but later came to me in bizarre partnership with her alleged rapist to demand $50,000 in exchange for keeping quiet about the situation). The dizzying mixture of interpersonal grievances had somehow distilled themselves into two camps: for and against the DxE leadership team. And in a straw poll of some of our core members, over 90% voted to throw out the people who were against our leadership team, based on the bad behavior they had seen.

But, in one of my first actions as the newly-elected lead organizer of DxE, I declined to take that action. Two people were removed from a mailing list, provisionally, due to personal insults they had made of other DxE organizers. But none of the other offenders – including people who later admitted to “stabbing Wayne in the back” – would be punished or banned. While unpopular at the time, it was the best decision I ever made.

The reason for this decision was that I felt punishing the signatories would lead to a spiral of conflict that would everyone feeling unsafe to take risks or speak their mind [ [link removed] ]. Progressive movements have long been plagued by what I’ve called the Politics of Punishment [ [link removed] ]. Activists — who have a predisposition for pointing out society’s failings — start pointing out each others’ failings, too. And the cycle of recrimination drives everyone to stay home. Choosing a compassionate approach, I thought, was the only way to short-circuit this dangerous dynamic and build a stronger foundation for a movement to grow.

And that decision, I think, proved to be the right one. The next year of activism was among the most inspiring in animal rights history, with hundreds of activists risking arrest to challenge the largest animal-abusers in the world [ [link removed] ]. The bitterness of the conflict disappeared. And, even as we had contentious disagreements within DxE — for example, over support for Prop 13, a ballot initiative that was hotly contested within the animal rights movement – we found ways to not just work with, but care for, each other.

The importance of radical compassion, i.e., kindness towards even those we are in conflict with, is just one of the many leadership lessons I’ve learned in the last ten years. And my conversation with Almira last week [ [link removed] ], as DxE faces unprecedented challenges posed by both government repression and widespread cynicism about change, made me think of some others. Interestingly, what I’ve learned about leadership is that many of the traditional attributes associated with leadership –oratorical ability, self-confidence, etc. – aren’t actually that important. What is important — and what is the common thread through all these lessons – is skill in bringing a team and community together.

Here are a few of those lessons.

Leadership is curious. Curiosity is not commonly associated with strong leadership, but a study by Harvard Business School [ [link removed] ] found it to be among the most important attributes. The most obvious reason that curiosity is important is that it allows leaders to show that they genuinely care. Leaders who aren’t curious about their team members’ problems will discourage their team members from working hard to solve them. But curiosity also inspires a culture of openness and engagement that allows everyone to be their best selves. When we see leaders opening themselves to new people, strategies, and even philosophies, we feel open, too.

Leadership is social. Some of the best leaders I’ve seen aren’t particularly good communicators, and don’t make a great first impression. They stumble over their words, and don’t come across as compelling personalities. But, even if they are not impressive, at first, all good leaders are social, i.e., they cultivate relationships between team members.

A long-time leader of a DxE working group, for example, would invite his team members to a local community workspace to hang out and work together. They would grab food and play video games together, after working. He would ask how his team members were doing, and show genuine interest in both their goals and their struggles. And by bringing the team together in shared spaces, he built relationships between his team members. It became one of the most successful teams in DxE.

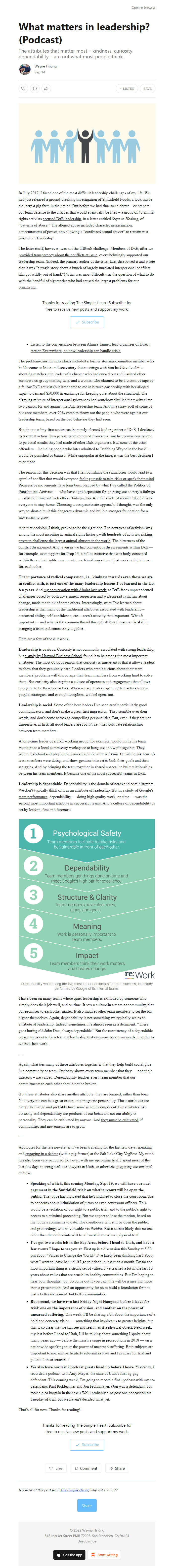

Leadership is dependable. Dependability is the domain of nerds and administrators. We don’t typically think of it as an attribute of leadership. But in a study of Google’s team performance [ [link removed] ], dependability — doing high quality work, on time — was the second most important attribute in successful teams. And a culture of dependability is set by leaders, first and foremost.

I have been on many teams where quiet leadership is exhibited by someone who simply does their job well, and on time. It sets a culture in a team or community, that our promises to each other matter. It also inspires other team members to set the bar higher themselves. Again, dependability is not something we typically see as an attribute of leadership. Indeed, sometimes, it’s almost seen as a detriment. “There goes boring old John Doe, always dependable.” But the consistency of a dependable person turns out to be a form of leadership that everyone on a team needs, in order to do their best work.

—

Again, what ties many of these attributes together is that they help build social glue in a community or team. Curiosity shows every team member that they — and their interests – are valued. Dependability teaches every team member that our commitments to each other should not be broken.

But these attributes also share another attribute: they are learned, rather than born. Not everyone can be a great orator, or a magnetic personality. Those attributes are harder to change and probably have some genetic component. But attributes like curiosity and dependability are products of our behavior, not our ability or personality. They can be cultivated by anyone. And they must be cultivated [ [link removed] ], if communities and movements are to grow.

—

Apologies for the late newsletter. I’ve been traveling for the last few days, speaking [ [link removed] ] and engaging in a debate [ [link removed] ] (with a pig farmer) at the Salt Lake City VegFest. My mind has also been very occupied, however, with my upcoming trial. I spent most of the last few days meeting with our lawyers in Utah, or otherwise preparing our criminal defense.

Speaking of which, this coming Monday, Sept 19, we will have our next argument in the Smithfield trial: on whether court will be open the public. The judge has indicated that he’s inclined to close the courtroom, due to concerns about intimidation of jurors or even courtroom officers. This would be a violation of our right to a public trial, and to the public’s right to access to a criminal proceeding. But we expect to lose the motion, based on the judge’s comments to date. The courthouse will still be open the public, and proceedings will be viewable via WebEx. But it seems likely that no one other than the defendants will be allowed in the actual physical trial.

I’ve got two weeks left in the Bay Area, before I head to Utah, and have a few events I hope to see you at. First up is a discussion this Sunday at 5:30 pm about “Values to Change the World [ [link removed] ].” I’ve lately been thinking hard about what I want to leave behind, if I go to prison in less than a month. By far the most important thing is a strong set of values. I’ve learned a lot in the last 10 years about values that are crucial to healthy communities. But I’m hoping to hear your thoughts, too. So come out if you can; this will be a meeting more than a presentation. And an opportunity for us to build a foundation for not just a better movement, but better communities.

But second, we have two last Friday Night Hangouts before I leave for trial: one on the importance of vision, and another on the power of unearned suffering. This week, I’ll be sharing a bit about the importance of a bold and concrete vision — something that inspires us to greater heights, but that is so clear that we can see and feel it, as if a physical object. Next week, my last before I head to Utah, I’ll be talking about something I spoke about many years ago — before the massive surge in prosecutions in 2018 — on a nationwide speaking tour: the power of unearned suffering. Both subjects are important to me, and particularly relevant as Paul and I prepare for trial and potential incarceration. I

We also have our last 2 podcast guests lined up before I leave. Yesterday, I recorded a podcast with Amy Meyer, the state of Utah’s first ag-gag defendant. This coming week, I’m going to record a final podcast with my co-defendants Paul Picklesimer and Jon Frohnmayer. (Jon was a defendant, but took a plea bargain in the case.) We’ll probably also post one podcast on the Tuesday of trial, but we haven’t decided what yet.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

In July 2017, I faced one of the most difficult leadership challenges of my life. We had just released a ground-breaking investigation [ [link removed] ] of Smithfield Foods, a look inside the largest pig farm in the nation. But before we had time to celebrate – or prepare our legal defense [ [link removed] ] to the charges that would eventually be filed – a group of 43 animal rights activists accused DxE leadership [ [link removed] ], in a letter entitled Steps to Healing, of “patterns of abuse.” The alleged abuse included character assassination, concentrations of power, and allowing a “confessed sexual abuser” to remain in a position of leadership.

The letter itself, however, was not the difficult challenge. Members of DxE, after we provided transparency about the conflicts at issue [ [link removed] ], overwhelmingly supported our leadership team. (Indeed, the primary author of the letter later disavowed it and wrote [ [link removed] ] that it was “a tragic story about a bunch of largely unrelated interpersonal conflicts that got wildly out of hand.”) What was most difficult was the question of what to do with the handful of signatories who had caused the largest problems for our organizing.

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Listen to the conversation between Almira Tanner, lead organizer of Direct Action Everywhere, on how leadership can handle crisis. [ [link removed] ]

The problem-causing individuals included a former steering committee member who had become so bitter and accusatory that meetings with him had devolved into shouting matches; the leader of a chapter who had cursed out and insulted other members on group mailing lists; and a woman who claimed to be a victim of rape by a fellow DxE activist (but later came to me in bizarre partnership with her alleged rapist to demand $50,000 in exchange for keeping quiet about the situation). The dizzying mixture of interpersonal grievances had somehow distilled themselves into two camps: for and against the DxE leadership team. And in a straw poll of some of our core members, over 90% voted to throw out the people who were against our leadership team, based on the bad behavior they had seen.

But, in one of my first actions as the newly-elected lead organizer of DxE, I declined to take that action. Two people were removed from a mailing list, provisionally, due to personal insults they had made of other DxE organizers. But none of the other offenders – including people who later admitted to “stabbing Wayne in the back” – would be punished or banned. While unpopular at the time, it was the best decision I ever made.

The reason for this decision was that I felt punishing the signatories would lead to a spiral of conflict that would everyone feeling unsafe to take risks or speak their mind [ [link removed] ]. Progressive movements have long been plagued by what I’ve called the Politics of Punishment [ [link removed] ]. Activists — who have a predisposition for pointing out society’s failings — start pointing out each others’ failings, too. And the cycle of recrimination drives everyone to stay home. Choosing a compassionate approach, I thought, was the only way to short-circuit this dangerous dynamic and build a stronger foundation for a movement to grow.

And that decision, I think, proved to be the right one. The next year of activism was among the most inspiring in animal rights history, with hundreds of activists risking arrest to challenge the largest animal-abusers in the world [ [link removed] ]. The bitterness of the conflict disappeared. And, even as we had contentious disagreements within DxE — for example, over support for Prop 13, a ballot initiative that was hotly contested within the animal rights movement – we found ways to not just work with, but care for, each other.

The importance of radical compassion, i.e., kindness towards even those we are in conflict with, is just one of the many leadership lessons I’ve learned in the last ten years. And my conversation with Almira last week [ [link removed] ], as DxE faces unprecedented challenges posed by both government repression and widespread cynicism about change, made me think of some others. Interestingly, what I’ve learned about leadership is that many of the traditional attributes associated with leadership –oratorical ability, self-confidence, etc. – aren’t actually that important. What is important — and what is the common thread through all these lessons – is skill in bringing a team and community together.

Here are a few of those lessons.

Leadership is curious. Curiosity is not commonly associated with strong leadership, but a study by Harvard Business School [ [link removed] ] found it to be among the most important attributes. The most obvious reason that curiosity is important is that it allows leaders to show that they genuinely care. Leaders who aren’t curious about their team members’ problems will discourage their team members from working hard to solve them. But curiosity also inspires a culture of openness and engagement that allows everyone to be their best selves. When we see leaders opening themselves to new people, strategies, and even philosophies, we feel open, too.

Leadership is social. Some of the best leaders I’ve seen aren’t particularly good communicators, and don’t make a great first impression. They stumble over their words, and don’t come across as compelling personalities. But, even if they are not impressive, at first, all good leaders are social, i.e., they cultivate relationships between team members.

A long-time leader of a DxE working group, for example, would invite his team members to a local community workspace to hang out and work together. They would grab food and play video games together, after working. He would ask how his team members were doing, and show genuine interest in both their goals and their struggles. And by bringing the team together in shared spaces, he built relationships between his team members. It became one of the most successful teams in DxE.

Leadership is dependable. Dependability is the domain of nerds and administrators. We don’t typically think of it as an attribute of leadership. But in a study of Google’s team performance [ [link removed] ], dependability — doing high quality work, on time — was the second most important attribute in successful teams. And a culture of dependability is set by leaders, first and foremost.

I have been on many teams where quiet leadership is exhibited by someone who simply does their job well, and on time. It sets a culture in a team or community, that our promises to each other matter. It also inspires other team members to set the bar higher themselves. Again, dependability is not something we typically see as an attribute of leadership. Indeed, sometimes, it’s almost seen as a detriment. “There goes boring old John Doe, always dependable.” But the consistency of a dependable person turns out to be a form of leadership that everyone on a team needs, in order to do their best work.

—

Again, what ties many of these attributes together is that they help build social glue in a community or team. Curiosity shows every team member that they — and their interests – are valued. Dependability teaches every team member that our commitments to each other should not be broken.

But these attributes also share another attribute: they are learned, rather than born. Not everyone can be a great orator, or a magnetic personality. Those attributes are harder to change and probably have some genetic component. But attributes like curiosity and dependability are products of our behavior, not our ability or personality. They can be cultivated by anyone. And they must be cultivated [ [link removed] ], if communities and movements are to grow.

—

Apologies for the late newsletter. I’ve been traveling for the last few days, speaking [ [link removed] ] and engaging in a debate [ [link removed] ] (with a pig farmer) at the Salt Lake City VegFest. My mind has also been very occupied, however, with my upcoming trial. I spent most of the last few days meeting with our lawyers in Utah, or otherwise preparing our criminal defense.

Speaking of which, this coming Monday, Sept 19, we will have our next argument in the Smithfield trial: on whether court will be open the public. The judge has indicated that he’s inclined to close the courtroom, due to concerns about intimidation of jurors or even courtroom officers. This would be a violation of our right to a public trial, and to the public’s right to access to a criminal proceeding. But we expect to lose the motion, based on the judge’s comments to date. The courthouse will still be open the public, and proceedings will be viewable via WebEx. But it seems likely that no one other than the defendants will be allowed in the actual physical trial.

I’ve got two weeks left in the Bay Area, before I head to Utah, and have a few events I hope to see you at. First up is a discussion this Sunday at 5:30 pm about “Values to Change the World [ [link removed] ].” I’ve lately been thinking hard about what I want to leave behind, if I go to prison in less than a month. By far the most important thing is a strong set of values. I’ve learned a lot in the last 10 years about values that are crucial to healthy communities. But I’m hoping to hear your thoughts, too. So come out if you can; this will be a meeting more than a presentation. And an opportunity for us to build a foundation for not just a better movement, but better communities.

But second, we have two last Friday Night Hangouts before I leave for trial: one on the importance of vision, and another on the power of unearned suffering. This week, I’ll be sharing a bit about the importance of a bold and concrete vision — something that inspires us to greater heights, but that is so clear that we can see and feel it, as if a physical object. Next week, my last before I head to Utah, I’ll be talking about something I spoke about many years ago — before the massive surge in prosecutions in 2018 — on a nationwide speaking tour: the power of unearned suffering. Both subjects are important to me, and particularly relevant as Paul and I prepare for trial and potential incarceration. I

We also have our last 2 podcast guests lined up before I leave. Yesterday, I recorded a podcast with Amy Meyer, the state of Utah’s first ag-gag defendant. This coming week, I’m going to record a final podcast with my co-defendants Paul Picklesimer and Jon Frohnmayer. (Jon was a defendant, but took a plea bargain in the case.) We’ll probably also post one podcast on the Tuesday of trial, but we haven’t decided what yet.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading The Simple Heart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a