|

How to Speak Your Mind

The world needs truth more than ever. So why are we all afraid to speak it?

| ||||||||||||

In March 2022, the New York Times editorial page made a surprising declaration: America Has a Free Speech Problem. Free speech, for the most part, has become a right-wing motto. But here was the Times, liberal paper of record, stating that “84 percent of adults [say] it is a ‘very serious’ or ‘somewhat serious’ problem that some Americans do not speak freely in everyday situations because of fear of retaliation or harsh criticism.” As one survey respondent put it:

“You can’t give people the benefit of the doubt to just hold a conversation anymore. You’ve got to worry about feeling judged. Political views can even affect your family ties, how you relate to your uncle or the other side. It’s really not good.”

This fear extends to even those in positions of privilege. Cass Sunstein is a powerful person. The most cited law professor of the last generation, Sunstein was appointed by President Barack Obama to be the head of the little-known Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). While not as well known as the Supreme Court, however, OIRA arguably has even more power because most law is regulatory, and not statutory.

Given Sunstein’s influence, it’s perhaps not surprising that he has not been afraid to be bold: arguing for the government to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to stop climate change, years before it was a “hot” issue in the mainstream; warning of the dangers of digital communications 20 years before The Social Dilemma popularized concerns about the impacts of social media; and writing that “we should celebrate tax day” in 1999, shortly after President Bill Clinton (a Democrat) declared, “The era of big government is over.”

But there is one issue that has left Sunstein paralyzed, and unable to speak his mind: animal rights. As he recently wrote:

Those who care about animal welfare often silence themselves. They know that if they speak out or act, they may incur disapproval from their peers. Personal experience shows me this is true. When Barack Obama, the US president at the time, nominated me to head the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, I had to be confirmed by the Senate. The process turned out to be surreal, a living nightmare. I was said to be “a rabid supporter of animal rights” who would forbid meat-eating and ban fishing and hunting. I received credible death threats at my unlisted home address. Mike Huckabee, the former governor of Arkansas, vaguely threatened me (with gunfire) if I visited his home state. The conservative talk show host Glenn Beck repeatedly described me as “the most dangerous man in America”.

The rage and the threats had an effect. Whenever I have spoken about animal welfare since that time, I have done so with trepidation and (I confess) a little fear.

I know this about Cass because he saw it firsthand. He was one of my key mentors in law school, and I co-authored work with him arguing that, even from a purely economic perspective, the fight against climate change justified spending $1-3 out of every $100 in the United States on protecting natural ecosystems. It was a daring argument that I was surprised Cass was willing to endorse. But when I later asked him to endorse grassroots efforts to ban foie gras in Chicago, he declined.

“I’m not quite comfortable with that,” Cass told me. I didn’t quite understand at the time. But then, a couple years later, the OIRA appointment crisis blew up on Fox News, and I saw firsthand how much Cass paid for his relatively benign support for animal rights.

What is true for Cass is true for so many others. Indeed, it was true for me. When I told senior faculty members at Northwestern, where I held a faculty appointment in the mid 2000s, that I wanted to write about animals, I universally received the same advice:

“That’s not something that’s going to get you tenure. You don’t want to out yourself as doing something that seems weird.”

Their assessment seemed correct. But my heart was pulling me in a different direction than my head. And, as I shared on Ezra Klein’s podcast, my heart won. I decided to continue speaking and writing on animals. And, five years after leaving Northwestern, co-founded the grassroots network Direct Action Everywhere. One of our informal mottos was: Speak the truth, even if your voice shakes.

Thousands of people across the globe joined us in doing just that.

Ten years later, however, we are living in a very different world. The free-wheeling culture of the internet has led to as much self-silencing as self-expression. College campuses that were once forums for intellectual exploration became spaces of self-censorship instead, with 80% of students now saying they sometimes self-censor. And movements, organizations, and families that should be working together, find themselves at odds over the smallest of disagreements. (I’ve previously written about this narcissism of small differences.)

This is not just problematic, however, for those who care about speech. It matters immensely for those who care about change. Because, to the extent our society is unable to tolerate disagreement and expression, it can’t move forward or make progress. In one of the largest studies of workplace productivity that has ever been done, Google found that “psychological safety” was the single most important factor in determining whether a team can make change.

But “psychological safety,” in the social scientific literature, means something completely different from the movement towards safer spaces that has grown from college campuses to the entire world. Indeed, in many ways, it is the exact opposite of a safer space. Safety, as Google’s research defined it, was not about protecting people from uncomfortable opinions but rather protecting those uncomfortable opinions.

Psychological safety is ‘‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up.”

Those who don’t want change need not worry about this. An organization or movement’s inability to make progress does not matter to those who prefer the status quo. But for those who seek change, creating “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up” is an essential part of what we must do. And, with 80+% of Americans and students saying, in various forms, that we are failing at that task, we need to course correct immediately.

But how can it be done? Much of the work that must be done is systemic, at the level of building norms and institutions that support a culture of candor. But I’ve learned, through difficult experiences in a variety of social settings (movements, law firms, academic institutions), that there are a few things we can do, on an individual level, to more effectively speak our mind, as well. The first is quite simple:

Practice. When I was a young graduate student at the University of Chicago, I attended one of the most famous workshops at the university – the Law and Economics workshop – which regularly hosted luminaries in the field. It was un-notable for a Nobel Prize winner to walk through the door. Yet the discussion was incredibly vigorous, and young faculty members and (occasionally) grad students seemed unafraid to challenge legendary figures in the field.

I asked one of my professors how I could become one of them. And he gave me simple advice. Read the paper carefully. Identify one question or criticism. And practice delivering the question so that, when the moment comes, you know what you want to say.

I took his advice. And while it was still incredibly difficult to speak, the first time I asked a question, it came out more smoothly than it would have, if I had not tried.

Get feedback. The second lesson came from a diverse body of research on what’s called “deliberate practice.” On everything from playing violin to learning math, practice is not enough. The practice needs to get regular, real-time feedback in order to improve your confidence – and your results. While I would practice delivering a question at the workshop, I often would have no idea how people would respond to the question. I was lost in my own mind. Getting feedback was the cure.

Feedback, ideally from people who represent the audience you are trying to change, is absolutely crucial to understanding the impact of your words, and even if the point you are making is clear. The shock we receive, from saying something and having our audience turn on us, is avoided if we can anticipate how people are going to receive what we are going to say, before we say it. Two things about feedback, however, are crucial. First, the feedback has to be from people who will be honest. This is harder than it should be, but we can make it easier by showing that we genuinely want it – and won’t punish people for telling us how they actually feel. (I feel this way about less than 10% of people, even those I consider my friends.) Second, the feedback has to come from people we trust. If the things we say, when we are still formulating our thoughts, are used against us, we won’t be able to sustain ourselves in speaking our truth.

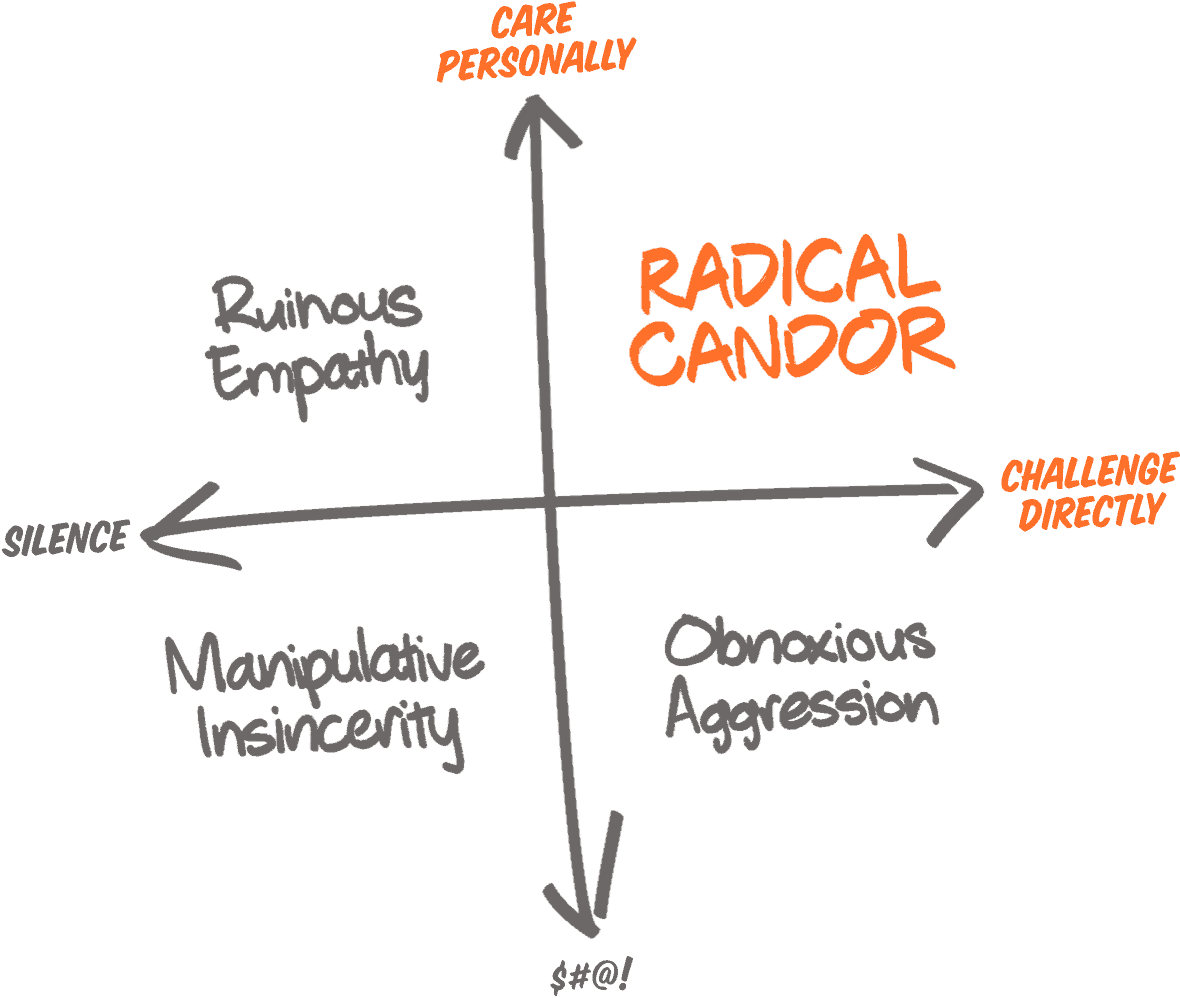

Just say it. The third and final thing I’ve learned, which is also advice given by the author of the book Radical Candor, is to “just say it.” We can spend enormous amounts of time practicing, getting feedback, or even just reflecting endlessly on what we want to say. But at the end of the day, a culture of candor depends on people having the courage to just say what they think, even if it’s hard. This can come at very steep personal costs. When I performed experiments on truth many years ago, as a young law student in the mid 2000s, it damaged my reputation and personal relationships tremendously. I tried to never tell anyone even little white lies. If they asked me, “What do you think of this paper I wrote?” and I thought, “It’s crap” – then that’s exactly what I would say.

But while that experience did short term damage to my relationships and reputation, it built a longer-term foundation for truth-speaking – to the point that I am now confident to speak my truth even in the face of incarceration or mob beatings – for two reasons. First, “just saying it” built my emotional callouses and prevented me from catastrophizing. I realized that I could survive whatever backlash I’d face for speaking truth, and that I often exaggerated the negative impacts of being honest - especially if my honesty came in a caring form. Second, and even more important, however, was what truth-speaking did to me. When I was forced to reckon with how my sometimes negative feelings impacted the people around me, I realized that my negativity: (a) was not really based in fact; and (b) had very little use.

Take, for example, the example of the crappy paper. When I disclosed to people exactly what was on my mind, I thought I was speaking a fact – that the paper was crap. But even if the writing or argument were not yet perfectly clear, my focus on the paper’s crappy aspects was not a fact, but a choice that I was making to emphasize these crappy aspects over other aspects that might be more positive. Perhaps the question being asked was an interesting one. Perhaps the data accumulated was compelling. Or perhaps the writer simply made a tremendous and praiseworthy effort – even if the finished product was not quite there. When I was asked “What do you think of this paper?” I could have been thinking any of those things, too. And when I forced myself to actually come forward with my views, I started shifting towards those more positive framings.

My hope is that we can apply this lesson to the world. A more open world is also a more positive one. It’s one where we can each not only feel safe to be ourselves, but to take risks to make the world a better place. There are lots of things, at the systemic level, that we can do to achieve this sort of world. But we can also each play a personal role. It starts with speaking your mind.

–

I’m in Salt Lake City tomorrow at the SLC VegFest – come and hang out! I’ll be speaking at 1 pm in the auditorium, joining an “Ask the Investigator” panel at the outdoor amphitheater at 2 pm, then engaging in a debate with pig farmer Trent Loos back at the auditorium at 3.

Tonight’s Friday Night Hangout is occurring as usual – and the focus is “how to speak your mind.” Dean and Priya will facilitate, but I’ll join briefly by Zoom. Here’s the event page.

Yesterday, the court ruled that the jury in my upcoming Utah trial will be anonymous, on the grounds that media attention may subject the jurors to intimidation and harassment. We believe this ruling violates our rights to a fair trial, as it immediately conveys to jurors that Paul and I are dangerous people. I commented about this on this livestream.

I’m going to pause the usual weekly survey for the next few weeks, as I have a few topics I want to write about before trial. We’ll start up the usual method – and the weekly acts of kindness – after trial. And that will be the case regardless of whether of what happens in court!

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?