|

This Doctor Fights to Prevent Nuclear War. Now He's Fighting Red Meat. (Podcast)

What does science actually say about the dangers of eating meat?

| ||||||||||||

In the last few years, we’ve seen a global health crisis that has tested the public’s faith in science. Even as millions of people have died, many refuse to believe the data that shows that we are facing unprecedented threats, including an increasing rate of death that is 19% higher than it should otherwise be.

But I’m not talking about COVID-19. I’m talking about red meat.

Check out my podcast with Dr. Michael Martin, a professor of epidemiology at UCSF, on what science actually says about the dangers of eating meat.

Mike believes red meat is among the greatest threats to public health in society today. And he knows of which he speaks. Mike is not just a trained epidemiologist who has published research on everything from firearms to skin damage. He is an advocate who has been leading the charge for years against some of the most pressing threats facing human civilization. For example, he’s the President of Physicians for Social Responsibility, the US-affiliate of a medical group that won the Nobel Prize in 1985 for sounding the alarm about the public health threat posed by nuclear war. He talks in our conversation about the prospect of conflict with Russia or China causing what’s called “nuclear winter” – a catastrophic global cooling event, triggered by nuclear detonations that send soot into the stratosphere, that could destroy human civilization as we know it.

But now he’s taking on another catastrophic threat: a food system based on red meat. And in terms of its lethality, the parallels between red meat and COVID-19 are a little eerie. In recent systematic reviews, both were associated with an exactly 19% increase in rates of death.¹

It might be surprising to hear me compare red meat to COVID-19 because I have always been skeptical of health arguments made by vegans. In my earlier days, the owner of a vegan restaurant in Chicago used to claim that veganism could lead to near-immortality. (He cited instances in the Bible of ancient figures, such as the 969-year old Methusellah, who apparently set the record for biblical longevity while living on the plant-based diet) And I have seen, in my 20+ years of veganism, countless plant-based fads come and go over the years, victims to their own flimsy scientific basis. My favorite was the sugar diet, a diet based entirely on processed sugars. (I tried it. It didn’t go so well.)

Health arguments for veganism, however, have only become more widespread. And some of the most popular in recent years have made me cringe. Take The Game Changers, a documentary that generated huge headlines when it was released in 2018. Produced by the legendary director James Cameron, the film argued that a plant-based diet was vastly superior to one based on animal foods. Perhaps the most memorable scene involved an “experiment” about erectile function.

Three athletes were given animal-meat burritos on Day 1. Then they were given plant-based burritos on Day 2. They were asked to sleep with an apparatus attached to their private parts that would measure erectile functions. The results were as shocking as they are hilarious: massive increases in both the intensity and duration of erectile activity.

“When you take your date out on Valentine’s Day, where are you going to take them to eat?” the doctor asks.

“To the Veggie Grill!”

But the methodology in this experiment was spurious. For one, there was no “control” variable – i.e. a set of participants who did NOT take the treatment at issue. The importance of controls is taught in the earliest stages of scientific education, and the lack of controls in any study should be a red flag that an experiment is not actually scientific. For another, the study only had 3 participants. That means the study lacked what scientists call “statistical power”; even with proper controls, the tiny numbers in the experiment mean that it could not have proven what it was trying to show,

The problem with bad scientific arguments, though, is not just that they are wrong but that they hurt the movement’s credibility. Experienced lawyers can tell you that when you combine a strong argument with a weak one, you end up losing both arguments because the weak one weakens the stronger. The jury trusts you less because you’re making an argument they simply don’t buy. There’s evidence that this applies more generally to persuasion. The psychologist Adam Grant reports in his book, Think Again, about experiments showing that weak arguments dilute the strong ones. I have long been concerned that, by focusing on health arguments with weak evidence, the animal rights movement is falling victim to this trap.

So how could I make the bombastic comparison between red meat and COVID-19 that I made at the start of this blog? And what can we actually say about the health impacts of eating animals, versus eating plant-based? I think there are now at least three important and credible claims we can make about health and meat.

The first is that eating red meat is associated with higher mortality. There is now significant data, including hundreds of thousands of participants, showing a statistical association between red meat and higher death rates. Cumulatively, one meta-study – performed ironically by researchers who had received funding by the food industry – found that there were associations, though not always statistically significant, between consumption of red meat and dying younger. Indeed, their report suggests that eating a serving of red meat per day is associated with a 19% increase in mortality, exactly the same percentage increase in mortality the nation saw in 2020 as a result of COVID-19.

However, the word “association” is key. Association is not causation, and people who eat plant-based are likely to engage in other healthy behaviors. They may be less likely to overeat. They may exercise more. They may have more access to health care. It is important, therefore, that we state only what can be justified: eating less red meat is associated with lower mortality – but we do not yet know the cause of that decrease. What seems very likely, however, is that the cluster of lifestyles associated with eating less red meat is better for human health than the average American diet.

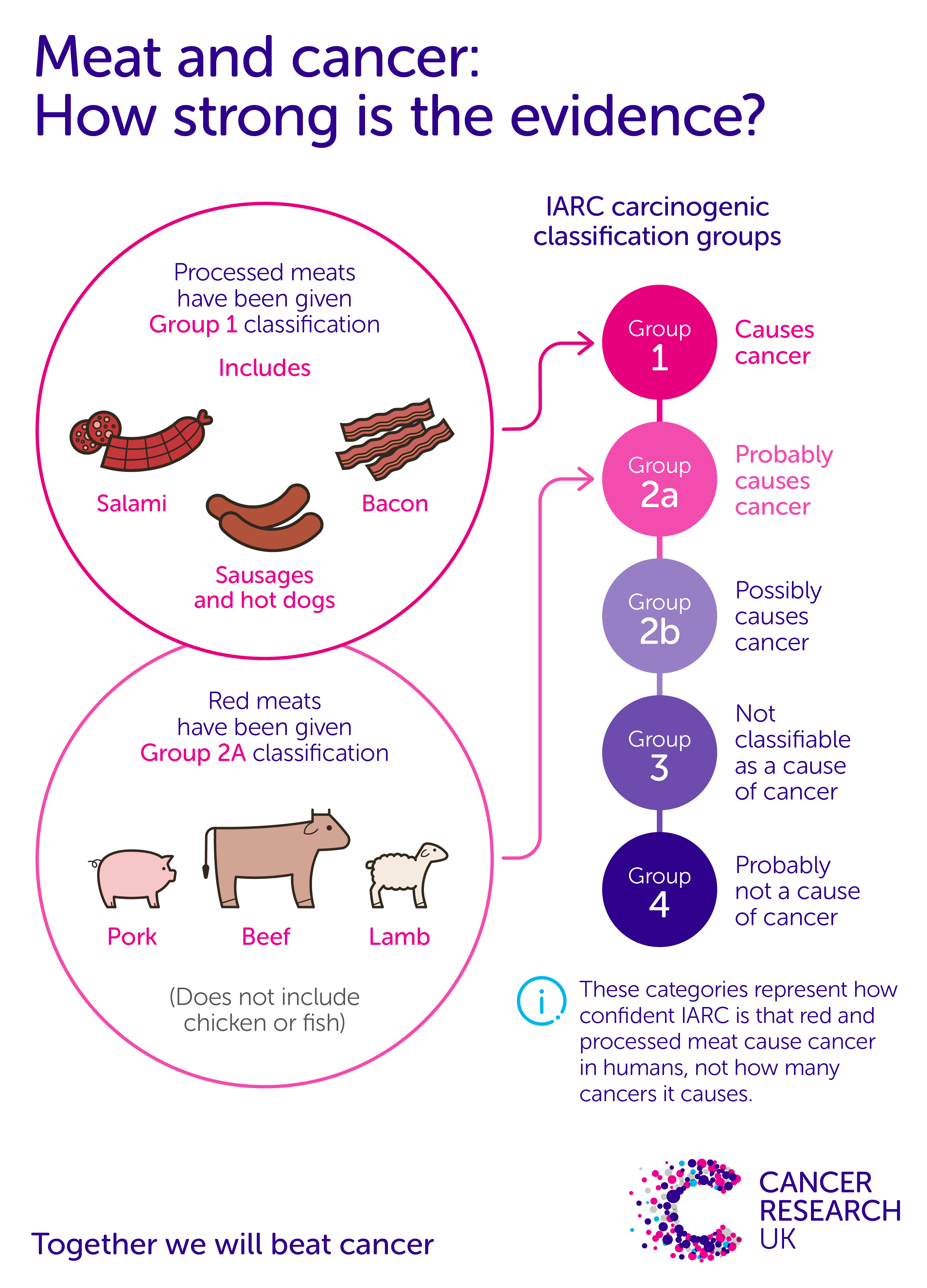

The second important and credible claim is that processed meat probably causes cancer. There are now numerous well-executed studies finding this result. And the WHO has declared processed meat a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning that there is convincing evidence that it causes cancer. The reason I hesitate and say that it “probably” causes cancer is that there have been numerous medical findings, over the last 20 years, that have been reversed in part because of a phenomenon called “publication bias.” Researchers report only findings that are interesting, and if you do a study enough times, you will eventually get that interesting finding. The doctor and researcher John Ionnidis at Stanford is famous for stating that, because of this, most published research findings in medical science are false. And he is right.

That means when we are making a causal, rather than associational, claim, we should be especially careful about what we say. Given the number of studies that show a connection between processed meat and cancer, it is fair to say that processed meats probably cause cancer. But there is also research showing that published results are likely biased, with 27 out of 29 published studies involving processed meats and colorectal cancer showing severe or critical errors, including missing data and selective outcome reporting, among other factors.

The third important and credible claim is that a plant-based diet is nourishing – for both the body and the soul. Claims about specific health benefits are hard to prove. Claims about the health and vitality of a plant-based diet, in contrast, are much easier to show, given the literally billions of people who have lived on a mostly plant-based diet. Virtually every major health organization in the nation agrees with this assessment. Consider the American Dietetic Associations statement:

It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases

Or the American Heart Association:

For adults both young and old, eating a nutritious, plant-based diet may lower the risk for heart attacks and other types of cardiovascular disease.

The American Medical Association has recently gone even further, in encouraging hospitals to offer plant-based meals.

[We] call on US hospitals to improve the health of patients, staff, and visitors by (1) providing a variety of healthful food, including plant-based meals and meals that are low in fat, sodium, and added sugars, (2) eliminating processed meats from menus…

Indeed, I am not aware of any study suggesting that human beings require any animal-based food. It would be surprising if that were the case, given that it’s almost incontrovertible that the vast majority of human foods through history have been plant-based.

The last point I will make on this topic, however, is not strictly evidentiary but conceptual. Plant-based food is not just good for the health of our body but of our soul. I don’t mean anything metaphysical, necessarily. While I’ve written about the positive impacts of religion, in the past, I am not a religious or spiritual person myself. I believe strictly in the physical universe. But human beings have evolved to be animals with purpose. And perhaps our highest purpose is kindness to others. It makes us connected. It makes us happy. It makes us understand who we were meant to be.

Eating plant-based gives every person an opportunity, three times a day, to nurture that purpose. And there is good evidence showing that people who live life with purpose, especially a purpose that helps those around them, are the ones who flourish most.

–

In short, there is now a reasonable evidentiary basis for at least three important and credible claims about plant-based eating. First, red meat is associated with higher rates of death – possibly in the same ballpark as the increases associated with COVID-19. Second, processed meats probably cause cancer. And third, plant-based diets are nourishing for the body, and the soul. These claims may not be as sexy or dramatic as what you see in a documentary or on tik tok. But they are much more likely to be true, and therefore enhance rather than undermine the long-term credibility of those advocating for change to our food system. I’d encourage everyone, therefore, to use these arguments, when you find them appropriate. Perhaps even this week, if you’re challenging yourself to invite a non-veg friend to join you for a vegan meal.

I’m being a little glib with this comparison. The COVID-19 data shows a nationwide 19% increase in all cause mortality between 2019 and 2020. The red meat data, according to Mike Martin, shows a 7% decrease in all cause mortality associated with a decrease in 3 serves of red meat per week. Mike states that implies that removing a serving of red meat once per day, or 7 servings per week, would lead to a 16% reduction in all cause mortality. That, in turn, implies that someone increasing their red meat consumption by one serving per day would increase their risk of all cause mortality by 19%. But the comparison is still not even remotely apples to apples. For one, not every person in the United States was exposed to COVID-19 in 2020. In contrast, the studies of red meat and mortality include data where every person in the red meat portion of the sample has actually been exposed to red meat. For another, the COVID-19 data has no controls, so it’s possible the increase in mortality in 2020 was caused by other factors, e.g., decreased access to medical care. The point I am making, however, is not that we can equate the death rates associated with red meat consumption and COVID-19, but that they are probably comparable within an order of magnitude – yet the threat posed by red meat has received relatively little attention.

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?