| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Subsidies Aren’t Enough. We Need Infrastructure, Sticks – And Research. |

| Date | August 20, 2022 1:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[After years of gridlock, there’s reason to celebrate Congress

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad. ]

[[link removed]]

SUBSIDIES AREN’T ENOUGH. WE NEED INFRASTRUCTURE, STICKS – AND

RESEARCH.

[[link removed]]

Daniel Cohan

August 19, 2022

The Conversation

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed].]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ After years of gridlock, there’s reason to celebrate Congress

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad. _

,

The new Inflation Reduction Act

[[link removed]]

is stuffed with subsidies for everything from electric vehicles to

heat pumps, and incentives for just about every form of clean energy.

But pouring money into technology is just one step toward solving the

climate change problem.

Wind and solar farms won’t be built without enough power lines to

connect their electricity to customers. Captured carbon and clean

hydrogen won’t get far without pipelines. Too few contractors are

trained to install heat pumps. And EV buyers will think twice if there

aren’t enough charging stations.

In my new book about climate solutions

[[link removed]],

I discuss these and other obstacles standing in the way of a clean

energy transition. Surmounting them is the next step as the country

figures out how to turn the goals of the most ambitious climate

legislation Congress has ever passed into reality.

Two outcomes matter: how deeply U.S. actions slash emissions

domestically, and how effectively they cut the costs of clean

technologies so that other countries can slash their emissions

[[link removed]]

too.

Infrastructure and obstacles

Various studies

[[link removed]]

predict [[link removed]] that

[[link removed]]

the Inflation Reduction Act will cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions to

around 40% below their 2005 levels by 2030. That’s a cut of roughly

1 billion tons per year, far more than any other U.S. legislation has

achieved.

But it still leaves a roughly 10 percentage point gap from President

Joe Biden’s target

[[link removed]]

of at least a 50% reduction in emissions by 2030.

What will it take to close that gap?

The Inflation Reduction Act’s subsidies will make clean technologies

cheaper, but the biggest need domestically is for more infrastructure

and stricter environmental regulations.

For infrastructure, tax credits for electric cars will do little good

without enough publicly available chargers. The U.S. has around

145,000 gas stations

[[link removed]], but

only about 6,500 fast-charging

[[link removed]]

stations that can power up a battery quickly for a driver on the go.

Over 1,300 gigawatts of wind, solar and battery projects – several

times the existing capacity – are already waiting to be built

[[link removed]], but they’ve been delayed for years by

a lack of grid connections and backlogged approval processes by

regional grid operators.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

[[link removed]]

passed by Congress last year provides some funding for chargers, power

lines and pipelines, but nowhere near enough. For example, it sets

aside only a few billion dollars for high-voltage power lines

[[link removed]],

a tiny share of the hundreds of billions of dollars needed

[[link removed]]

to chart a path toward net-zero emissions. Its $7.5 billion for

chargers is just a third of what electric car advocates project will

be needed

[[link removed]].

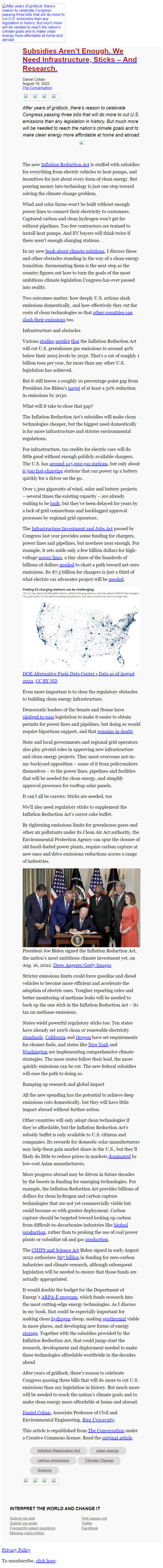

[Map of US EV charging stations show large numbers in the Northeast

and West Coast and US cities, but far fewer in less populated

regions.]DOE Alternative Fuels Data Center • Data as of August 2022

[[link removed]],

CC BY-ND [[link removed]]

Even more important is to clear the regulatory obstacles to building

clean energy infrastructure.

Democratic leaders of the Senate and House have pledged to pass

[[link removed]]

legislation to make it easier to obtain permits for power lines and

pipelines, but doing so would require bipartisan support, and that

remains in doubt

[[link removed]].

State and local governments and regional grid operators also play

pivotal roles in approving new infrastructure and clean energy

projects. They must overcome not-in-my-backyard opposition – some of

it from policymakers themselves – to the power lines, pipelines and

facilities that will be needed for clean energy, and simplify approval

processes for rooftop solar panels.

It can’t all be carrots: Sticks are needed, too

We’ll also need regulatory sticks to supplement the Inflation

Reduction Act’s carrot cake buffet.

By tightening emissions limits for greenhouse gases and other air

pollutants under its Clean Air Act authority, the Environmental

Protection Agency can spur the closure of old fossil-fueled power

plants, require carbon capture at new ones and drive emissions

reductions across a range of industries.

[Biden sits at a desk signing the legislation. Sens. Joe Manchin

(D-WV.) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Reps. James Clyburn (D-SC), Rep.

Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and Rep. Kathy Catsor (D-FL) look over his

shoulder.]President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the

nation’s most ambitious climate investment yet, on Aug. 16, 2022.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

[[link removed]]

Stricter emissions limits could force gasoline and diesel vehicles to

become more efficient and accelerate the adoption of electric ones.

Tougher reporting rules and better monitoring of methane leaks will be

needed to back up the one stick in the Inflation Reduction Act – its

tax on methane emissions.

States wield powerful regulatory sticks too. Ten states have already

set 100% clean or renewable electricity standards

[[link removed]].

California

[[link removed]]

and Oregon

[[link removed]] have set

requirements for cleaner fuels, and states like New York

[[link removed]] and Washington

[[link removed]] are

implementing comprehensive climate strategies. The more states follow

their lead, the more quickly emissions can be cut. The new federal

subsidies will ease the path to doing so.

Ramping up research and global impact

All the new spending has the potential to achieve deep emissions cuts

domestically, but they will have little impact abroad without further

action.

Other countries will only adopt clean technologies if they’re

affordable, but the Inflation Reduction Act’s subsidy buffet is only

available to U.S. citizens and companies. Its rewards for domestic

solar manufacturers may help them gain market share in the U.S., but

they’ll likely do little to reduce prices in markets dominated

[[link removed]]

by low-cost Asian manufacturers.

More progress abroad may be driven in future decades by the boosts in

funding for emerging technologies. For example, the Inflation

Reduction Act provides billions of dollars for clean hydrogen and

carbon capture technologies that are not yet commercially viable but

could become so with greater deployment. Carbon capture should be

targeted toward locking up carbon from difficult-to-decarbonize

industries like biofuel production

[[link removed]], rather than to prolong the

use of coal power plants or subsidize oil and gas production

[[link removed]].

The CHIPS and Science Act

[[link removed]]

Biden signed in early August 2022 authorizes $67 billion

[[link removed]]

in funding for zero-carbon industries and climate research, although

subsequent legislation will be needed to ensure that those funds are

actually appropriated.

It would double the budget for the Department of Energy’s ARPA-E

program [[link removed]], which funds research into the

most cutting-edge energy technologies. As I discuss in my book, that

could be especially important for making clean hydrogen

[[link removed]] cheap, making

geothermal [[link removed]] viable

in more places, and developing new forms of energy storage

[[link removed]]. Together with

the subsidies provided by the Inflation Reduction Act, that could

jump-start the research, development and deployment needed to make

these technologies affordable worldwide in the decades ahead.

After years of gridlock, there’s reason to celebrate Congress

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad.[The Conversation]

Daniel Cohan

[[link removed]], Associate

Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, _Rice University

[[link removed]]_

This article is republished from The Conversation

[[link removed]] under a Creative Commons license. Read

the original article

[[link removed]].

* Inflation Reducation Act

[[link removed]]

* clean energy

[[link removed]]

* carbon emissions

[[link removed]]

* Climate Change

[[link removed]]

* Science

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed].]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad. ]

[[link removed]]

SUBSIDIES AREN’T ENOUGH. WE NEED INFRASTRUCTURE, STICKS – AND

RESEARCH.

[[link removed]]

Daniel Cohan

August 19, 2022

The Conversation

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed].]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ After years of gridlock, there’s reason to celebrate Congress

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad. _

,

The new Inflation Reduction Act

[[link removed]]

is stuffed with subsidies for everything from electric vehicles to

heat pumps, and incentives for just about every form of clean energy.

But pouring money into technology is just one step toward solving the

climate change problem.

Wind and solar farms won’t be built without enough power lines to

connect their electricity to customers. Captured carbon and clean

hydrogen won’t get far without pipelines. Too few contractors are

trained to install heat pumps. And EV buyers will think twice if there

aren’t enough charging stations.

In my new book about climate solutions

[[link removed]],

I discuss these and other obstacles standing in the way of a clean

energy transition. Surmounting them is the next step as the country

figures out how to turn the goals of the most ambitious climate

legislation Congress has ever passed into reality.

Two outcomes matter: how deeply U.S. actions slash emissions

domestically, and how effectively they cut the costs of clean

technologies so that other countries can slash their emissions

[[link removed]]

too.

Infrastructure and obstacles

Various studies

[[link removed]]

predict [[link removed]] that

[[link removed]]

the Inflation Reduction Act will cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions to

around 40% below their 2005 levels by 2030. That’s a cut of roughly

1 billion tons per year, far more than any other U.S. legislation has

achieved.

But it still leaves a roughly 10 percentage point gap from President

Joe Biden’s target

[[link removed]]

of at least a 50% reduction in emissions by 2030.

What will it take to close that gap?

The Inflation Reduction Act’s subsidies will make clean technologies

cheaper, but the biggest need domestically is for more infrastructure

and stricter environmental regulations.

For infrastructure, tax credits for electric cars will do little good

without enough publicly available chargers. The U.S. has around

145,000 gas stations

[[link removed]], but

only about 6,500 fast-charging

[[link removed]]

stations that can power up a battery quickly for a driver on the go.

Over 1,300 gigawatts of wind, solar and battery projects – several

times the existing capacity – are already waiting to be built

[[link removed]], but they’ve been delayed for years by

a lack of grid connections and backlogged approval processes by

regional grid operators.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

[[link removed]]

passed by Congress last year provides some funding for chargers, power

lines and pipelines, but nowhere near enough. For example, it sets

aside only a few billion dollars for high-voltage power lines

[[link removed]],

a tiny share of the hundreds of billions of dollars needed

[[link removed]]

to chart a path toward net-zero emissions. Its $7.5 billion for

chargers is just a third of what electric car advocates project will

be needed

[[link removed]].

[Map of US EV charging stations show large numbers in the Northeast

and West Coast and US cities, but far fewer in less populated

regions.]DOE Alternative Fuels Data Center • Data as of August 2022

[[link removed]],

CC BY-ND [[link removed]]

Even more important is to clear the regulatory obstacles to building

clean energy infrastructure.

Democratic leaders of the Senate and House have pledged to pass

[[link removed]]

legislation to make it easier to obtain permits for power lines and

pipelines, but doing so would require bipartisan support, and that

remains in doubt

[[link removed]].

State and local governments and regional grid operators also play

pivotal roles in approving new infrastructure and clean energy

projects. They must overcome not-in-my-backyard opposition – some of

it from policymakers themselves – to the power lines, pipelines and

facilities that will be needed for clean energy, and simplify approval

processes for rooftop solar panels.

It can’t all be carrots: Sticks are needed, too

We’ll also need regulatory sticks to supplement the Inflation

Reduction Act’s carrot cake buffet.

By tightening emissions limits for greenhouse gases and other air

pollutants under its Clean Air Act authority, the Environmental

Protection Agency can spur the closure of old fossil-fueled power

plants, require carbon capture at new ones and drive emissions

reductions across a range of industries.

[Biden sits at a desk signing the legislation. Sens. Joe Manchin

(D-WV.) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Reps. James Clyburn (D-SC), Rep.

Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and Rep. Kathy Catsor (D-FL) look over his

shoulder.]President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the

nation’s most ambitious climate investment yet, on Aug. 16, 2022.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

[[link removed]]

Stricter emissions limits could force gasoline and diesel vehicles to

become more efficient and accelerate the adoption of electric ones.

Tougher reporting rules and better monitoring of methane leaks will be

needed to back up the one stick in the Inflation Reduction Act – its

tax on methane emissions.

States wield powerful regulatory sticks too. Ten states have already

set 100% clean or renewable electricity standards

[[link removed]].

California

[[link removed]]

and Oregon

[[link removed]] have set

requirements for cleaner fuels, and states like New York

[[link removed]] and Washington

[[link removed]] are

implementing comprehensive climate strategies. The more states follow

their lead, the more quickly emissions can be cut. The new federal

subsidies will ease the path to doing so.

Ramping up research and global impact

All the new spending has the potential to achieve deep emissions cuts

domestically, but they will have little impact abroad without further

action.

Other countries will only adopt clean technologies if they’re

affordable, but the Inflation Reduction Act’s subsidy buffet is only

available to U.S. citizens and companies. Its rewards for domestic

solar manufacturers may help them gain market share in the U.S., but

they’ll likely do little to reduce prices in markets dominated

[[link removed]]

by low-cost Asian manufacturers.

More progress abroad may be driven in future decades by the boosts in

funding for emerging technologies. For example, the Inflation

Reduction Act provides billions of dollars for clean hydrogen and

carbon capture technologies that are not yet commercially viable but

could become so with greater deployment. Carbon capture should be

targeted toward locking up carbon from difficult-to-decarbonize

industries like biofuel production

[[link removed]], rather than to prolong the

use of coal power plants or subsidize oil and gas production

[[link removed]].

The CHIPS and Science Act

[[link removed]]

Biden signed in early August 2022 authorizes $67 billion

[[link removed]]

in funding for zero-carbon industries and climate research, although

subsequent legislation will be needed to ensure that those funds are

actually appropriated.

It would double the budget for the Department of Energy’s ARPA-E

program [[link removed]], which funds research into the

most cutting-edge energy technologies. As I discuss in my book, that

could be especially important for making clean hydrogen

[[link removed]] cheap, making

geothermal [[link removed]] viable

in more places, and developing new forms of energy storage

[[link removed]]. Together with

the subsidies provided by the Inflation Reduction Act, that could

jump-start the research, development and deployment needed to make

these technologies affordable worldwide in the decades ahead.

After years of gridlock, there’s reason to celebrate Congress

passing three bills that will do more to cut U.S. emissions than any

legislation in history. But much more will be needed to reach the

nation’s climate goals and to make clean energy more affordable at

home and abroad.[The Conversation]

Daniel Cohan

[[link removed]], Associate

Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, _Rice University

[[link removed]]_

This article is republished from The Conversation

[[link removed]] under a Creative Commons license. Read

the original article

[[link removed]].

* Inflation Reducation Act

[[link removed]]

* clean energy

[[link removed]]

* carbon emissions

[[link removed]]

* Climate Change

[[link removed]]

* Science

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed].]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV