|

People don't trust institutions. And they're right not to.

From freaky persuasion to predatory AI, institutions are acting badly. Here's how we can fix them.

Today, our legal team filed a set of exhibits that we plan to introduce at trial in a case involving an open rescue at one of the largest pig farms in the nation, Smithfield’s Circle Four Farms. I’ve written about the case extensively, including what the case says about power and trust, and why the efforts by the prosecution and industry to gag us at trial will inevitably backfire. But even though I know this case is going to generate huge value for the movement — including mobilizing 100+ activists to join us in Utah to take on the largest pig production company in the world — it’s a hard getting through the slog.

The number of obstacles put up by the industry and government took a dramatic turn for the worse when the elected sheriff of Beaver County apparently threatened animal rights activists in Utah for merely having conversations about factory farming. The First Amendment, apparently, does not apply to those who criticize Smithfield in Beaver County — or at least that’s what’s alleged in suit filed against the authorities in Beaver last week. It should not be this hard to exercise our speech rights in a democracy — yet it is.

The same unnecessary difficulty is even more true of my battles in the court room. I’ve shared previously how my first arrest, in which I was slammed to concrete and charged with a felony for merely daring to hand out leaflets against a powerful local corporation, forever changed my view of law enforcement in this country. Through years of activism, however, I still held some faith in our legal system as a whole, especially compared to tinpot dictatorships such as China, where power and corruption combine in a toxic mix. (For example, to escape with three dogs we rescued from the Yulin Dog Meat Festival, without appropriate paperwork, we merely had to bribe the right people in China. And it wasn’t even that expensive!)

The last 4 years of court cases, sadly, have destroyed much of that faith in the American legal system.

I have always been a legal realist, recognizing that the law is a tool for exercising power, and not some principled ideal. Getting “the law” right, when it’s merely politics by other means, is not fundamentally different than getting morality right. But even as a realist, I thought there were constraints by which the law was used by the powerful in the United States. Call it the rule of law, civil liberties, checks and balances, or any of the other cliched terms used to lionize modern liberal democracies. In all cases, the result of the constraints on the raw exercise of power led to an important outcome: I (and many other Americans) trusted our legal system more than most people around the world.

Now I no longer hold that trust. Basic rights, such as the right to a complete defense under the 6th Amendment, which should in theory give me the right to call the witnesses or present the evidence that I deem necessary in a criminal trial, are routinely ignored. The right to free speech is not just disregarded by individual officers, but systematically dismantled by a government and industry that sees any dissent or disagreement as violence. (It’s worth noting that, as an alleged terrorist, my only supposed threats involve the threat to speak openly and truthfully about the things I’ve seen in factory farms.)

But perhaps the most troubling failure in our legal system is a failure of openness. Prosecutors, officers, and even judges nowadays seem unapologetic about “joining a team” rather than trying to serve justice. There’s some value in this candor. Better that a biased judge show his true colors than hide under the mask of neutrality. But what seems different and disturbing today is not just the lack of neutrality, but the lack of humility. Our legal system seems intent on getting to an outcome before there’s been any discussion of, well, the facts; the rules put in place, whether regarding the presentation of evidence or leafleting on a sidewalk, are twisted to reach that same goal: “helping our side win.”

Trying to persuade or change anyone in such a system, when your goals are not the same as the dominant team, is almost hilarious in its absurdity. The Utah trial, in which I have been barred from even playing video of the alleged crime, is just one example of this. I’ve lately started calling the efforts to persuade people in this system “freaky persuasion” because it’s weird and disturbing and always more difficult than it should be. It’s not persuasion as we ordinary understand it; it’s freaky. Like trying to play tennis blindfolded, and using your toes on the racquet instead of your hand.

Many Americans are apparently going through a similar experience in interacting with our institutions. The Gallup organization published poll results recently showing that Americans’ trust in virtually all institutions is falling to historic lows. Too many people have had experiences like mine. We feel jerked around and used, by powerful people operating in opaque and dishonest structures. The techno-industrial complex around us, that generates massive returns for the wealthiest but has led to a crisis of affordability for everyone else, feels like a predatory AI that is transforming our planet into corporate profit.

And it’s making us not just anxious and concerned, but mad as hell.

This is not the sign of a well functioning democracy; it is the sign of one that is deeply ill.

But even though I, like many Americans, am at a breaking point in my trust in our government and institutions, I am also more hopeful than I’ve ever been. And I think you should be, too.

First, the loss of trust feels like an overdue reckoning. My faith in police is one such example. There is no reason to trust an institution that has been so undeserving of trust. And building real trust, based on reality and truth, requires candor about the present and the past.

And this is what candor looks like: Our institutions, over the last 50 years, have failed us. After the surge in progress in the 1960s and 70s, when groundbreaking civil rights and environmental legislation was passed, and prosperity truly seemed to spread widely through Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs, we have been largely been treading water as a nation — or worse. Being honest about this lack of progress seems important.

Second, the loss of trust, while accompanied by many disturbing demographic trends, such as increasing suicides and loneliness, is also accompanied by vital breakthroughs on various issues, from gay rights to climate change. I’ve seen this firsthand in my work for animal rights. If someone had told me that I’d be standing on the steps of the California State Capitol building, shortly before the entire state banned the sale of fur in 2019, I would have probably laughed at you. But it’s real; it happened; and it was because of a movement of grassroots activists who were inspired to fight. And they were inspired partly because they knew that they couldn’t trust corporations and the government to do right by the animals. Distrust towards institutions that drives momentum for change, in short, is a form of distrust that works.

Third, while popular hope and trust are declining, there is increasing optimism for change among those who are closest to an issue. That caveat — “among those closest to an issue” — is an important one, and shows a potential weak point in my optimism. Doug McAdam, after all, shared with me that part of what drove progress for civil rights in the 1960s was that, despite the collective pain and outrage over lynchings and beatings and mass arrests of nonviolent activists, most Black people in the 1960s were highly optimistic about the prospect for positive change.

I don’t believe that’s true for most people, or even most activists, today, which leaves us in a perilous place. As Doug shared with me, change depends not just on a sense of outrage about the present, but also a shared sense of optimism and power about our future. In short, change requires hope and outrage. And we are missing the first of these ingredients.

Except that I find that those closest to an issue, who are studying it closely, are often the ones with the most hope. An example is Saul Griffith, the MacArthur “Genius” grant winning engineer who has spent a lifetime studying energy policy. Saul probably knows more about how to get to carbon neutrality than anyone in the world, and he’s very optimistic that we are on the right path, or at least a much better path than the one we were on just a few years ago.

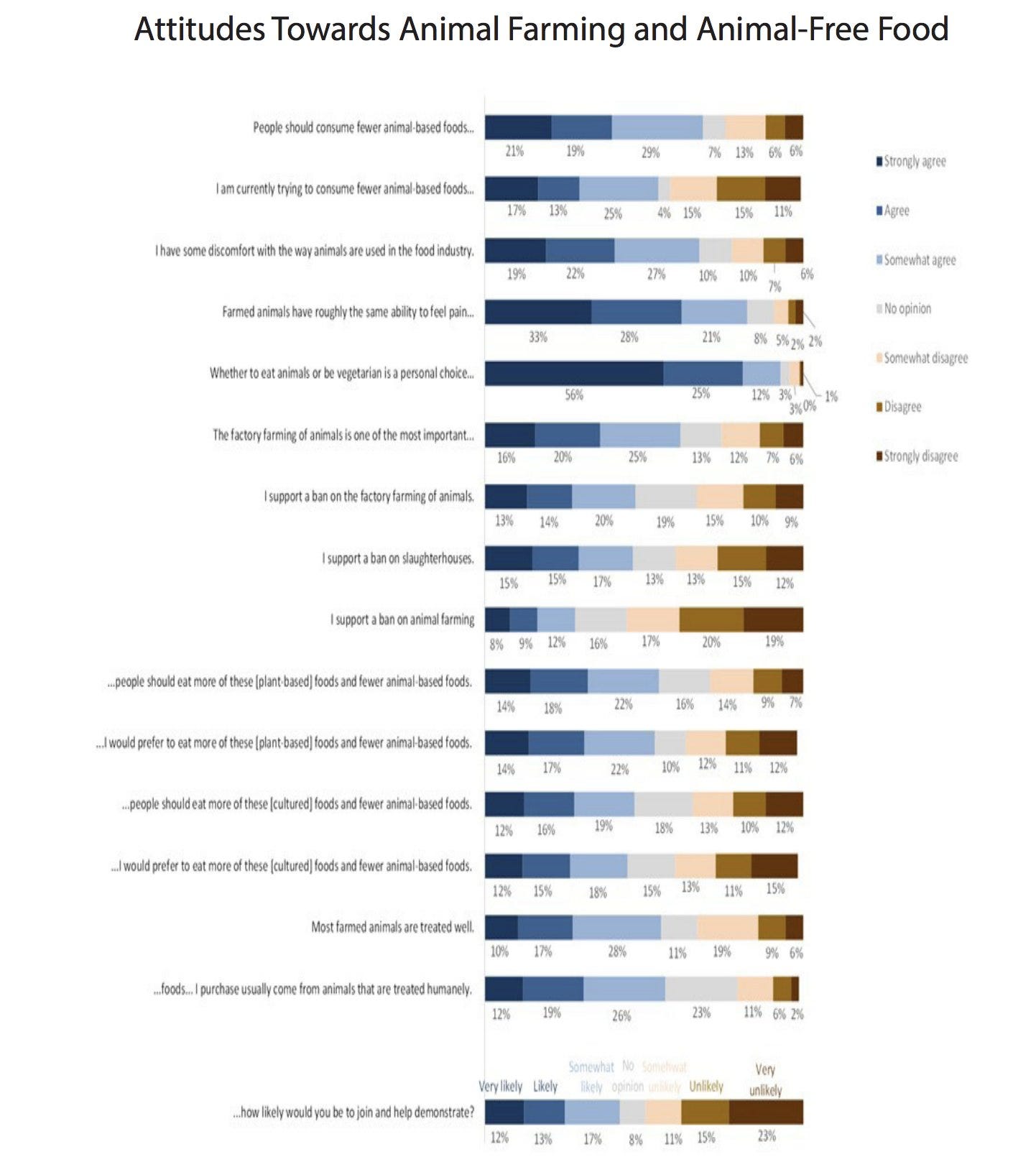

Another example can be drawn from my own life’s passion: animal rights. While many despair over the loss of species and the catastrophic suffering inflicted by factory farms, some of the folks who are looking most closely at the issue have gotten to surprisingly positive results. For example, the Sentience Institute did polling a few years back showing that half of Americans would choose to ban slaughterhouses if they were given the option. Half! And this poll was replicated by an agricultural economist, who works for the industry, who was shocked by the results.

What does this mean for those of concerned about declining optimism and trust? The first thing to say is that we should always look at the data in forming opinions, and not just the prevailing mood of those in our social circle, before we decide how likely a particular change might be. The second is that, to the extent we have no good data, we should look at experts who looking at the issue more closely than us, especially those who bear the markets of Phil Tetlock’s Good Judgment project, even if the mainstream views on an issue seem pessimistic or sad.

Using these standards, I have become much more optimistic about the prospects for change on issues such as animal rights. First, while some data on animals is looking bad, for example increasing global meat consumption, the key institutional data (e.g. nations banning fur, or making efforts to regulate factory farms) is very good, and so is public opinion. Second, experts who look closely at the issue seem to come down universally in favor of animal rights. It happened again recently on Ezra Klein’s most recent podcast, where and his guest both agree that, 300 years from now, people will look upon how we treat other species with utter horror. The moral weirdos of today will become the moral heroes of the future.

To get to that place, of course, requires lots of change in those 300 years. But that is where I have the biggest, ahem, plant-based bone to pick with Ezra and his guest. It won’t take 300 years for us to go from hot dog to historic horror. It’s going to happen in 40 years or less.

—

Stay tuned for the Friday Night Hangout discussion this week. The topic you all chose was “Mega-Corporations Cause Stockholm Syndrome: Why we love the corporations that hurt us.”

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?