How to Stop Lying

From factory farms to electoral politics, fraud is destroying the world. Here's what each of us can do to challenge that.

Lying is a bit like cancer. It might start small, with one problematic piece. But if not addressed, it quickly metastasizes and can destroy everything. In many ways, that’s what is happening today with our nation. Corporations deceive us about the health and environmental impacts of their products. Politicians mislead us with promises they don’t plan to keep, while working on behalf of their wealthy donors. Everyday people are increasingly susceptible to the most bizarre of conspiracy theories, which are as false as they are ludicrous. And each lie, like a cancer, builds on the last one, as each of us individually asks, “Well, if everyone else is lying, why should I tell the truth?”

But what is the cure? There are important lessons that can be drawn from the fight against food fraud: look for the proof; be radically candid; and demand collective transparency. The story here starts over 100 years ago, with a muckraking journalist who adventured into a slaughterhouse. And it ends with the modern effort to crush animal activists, by mega corporations like Smithfield, merely for attempting to tell the truth.

—

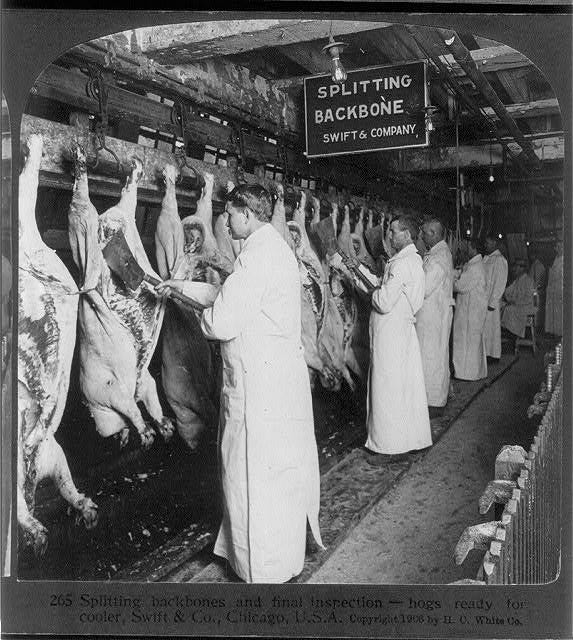

In 1904, Upton Sinclair went undercover in the slaughterhouse capital of the nation: the stockyards of Chicago. What he found was disturbing, even for a seasoned investigative journalist. Workers were operating in dangerous conditions, with deadly tools being used with little training or supervision. Filth, rot, and feces were everywhere. And what was being marketed as “meat” to the nation included all sorts of unsavory ingredients, including dead rats, cancerous tumors, and even the severed limbs of human beings.

The uproar over Sinclair’s novel detailing his experiences, The Jungle, led to the passage of a groundbreaking law: the Meat Inspection Act. For the first time, companies selling flesh would be inspected, and held accountable for their lies.

But the Meat Inspection Act, while initially celebrated by people across the nation, quickly became one of the industry’s greatest shields from scrutiny. Big Meat argued successfully in court that the Act gave the US Department of Agriculture the exclusive right to regulate the inspections of slaughterhouses, and the marketing of meat. And it quickly moved to “capture” the USDA, creating a revolving door between the C-suite offices of the largest meat and dairy producers and the highest leadership at the USDA. That has continued for generations, including the the most recent Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, who was formerly the President and CEO of the US Dairy Export Council, earning a cool $1 million dollars a year for apparently doing relatively little work.

The net result is that when states such as California have attempted to impose common sense regulations on the slaughter of animals or the marketing of meat, they’ve hit a dead end. Courts rule they lack the power to do so under the Meat Inspection Act. In short, the very law that Sinclair believed would stop the meat industry from lying, has now become a tool to shield them from accountability for their lies.

What was Sinclair’s mistake? He was right about the problem. The lies told by the slaughter industry were as problematic in 1904 as they are in 2022. But he was wrong about the solution. In particular, the top down effort to stop the lies did not work. Instead, as the food movement has shown over the last 100 years, effective solutions start from the bottom up. Here are three lessons that we should take from that experience.

Lesson 1: Look for proof. There’s evidence that the mere existence of a written statement biases human beings in favor of believing it. And we are, truth be told, extraordinarily gullible animals. Through most of our history, we had no reason to doubt what others told us. We lived in close-knit communities where any liars would quickly be outed and ostracized. That is far from how we live today, in a planet of nearly 8 billion people, all of whom are connected by communications technology unimaginable even in Sinclair’s time.

That makes it even more important to look for proof. When corporations such as Whole Foods (“Our animals are free range!”) and Smithfield (“We’ve ended the use of gestation crates!”) have made claims about animal welfare, most people have been inclined to believe their claims. Consumers, after all, are made happier by the belief that animals are treated kindly, even if it’s not true. Even animal advocacy organizations have a tendency towards believing statements of this sort because they are seen as a sign of movement progress.

But has anyone bothered to look for the proof? When I was in graduate school, a young superstar professor, Esther Duflo, was about to change the field of economics. She would eventually win a Nobel Prize and transformed the entire planet’s approach to problems such as poverty and disease. And there was one thing, above all else, that we all knew was different about Duflo. She was relentless about looking for proof.

“Esther won’t believe you when you say you had a sandwich for lunch without evidence,” we used to joke. But her focus on evidence and proof shifted economics away from the oft-unfalsifiable theories, or experiments performed on MIT undergraduates, towards real world evidence, so-called field experiments, that demonstrated the truth of a proposition outside of the lab.

All of us can learn from Duflo’s wisdom. And it is partly because of my experience in grad school that, though I was highly supportive of animal welfare certifications in the mid 2000s, I became increasingly skeptical because of the lack of proof. The search for proof, in turn, took me down a rabbit hole that I never could have imagined as a young economics graduate student in 2001. Among other things, we found Whole Foods was using sham farms for marketing purposes (while raising its actual animals in traditional factory farms), and that Smithfield was continuing to confine mother pigs in gestation crates (despite its CEO’s promise that the crate would be banned).

All of us can apply Duflo’s wisdom to our own lives. Instead of believing the latest internet outrage, or buying into the most viral belief or conspiracy theory, we should look for proof. And if we can’t answer the question, “What’s the proof?” we should be skeptical of the truth of the claim being made.

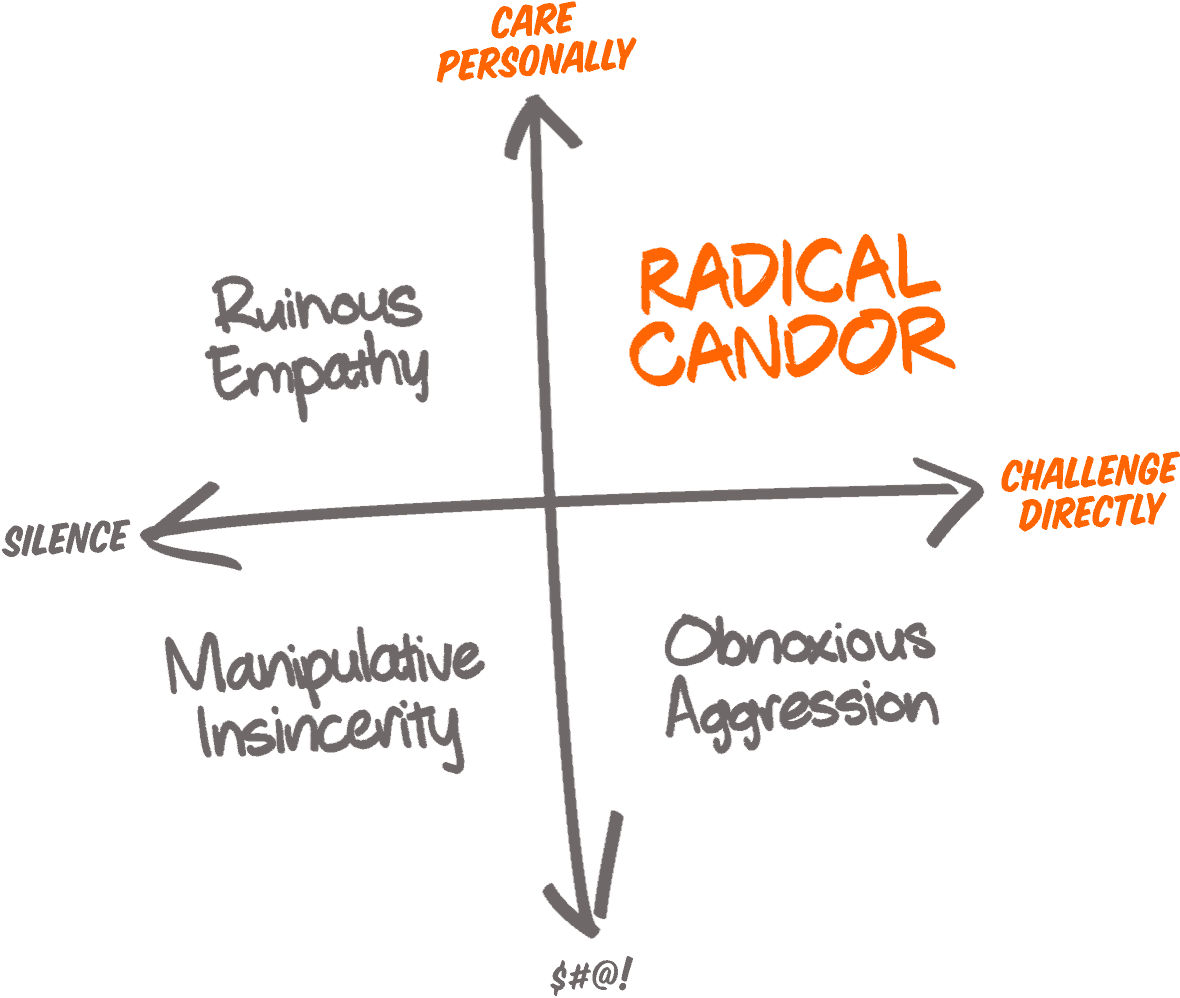

Lesson 2: Be radically candid. It’s not enough for us to look for proof, though. We have to be candid about what we find.

For many years, I approached advocacy as if I were walking on egg shells. I had too many people reacting with defensiveness or even anger to share confidently what I believed. This sensitivity is, in some ways, a good thing. The best persuaders are good listeners, too.

But what I and other animal advocates got wrong is that truth isn’t served by avoidance. It’s served by candor. And that is especially true in a distrustful world. Human beings are astonishingly good at detecting inauthenticity. And the best and strongest relationships, both in organizations and in our personal lives, are ones grounded in candor. But, as the noted leadership guru Kim Scott has argued, the key thing is that the candor must come with care.

I’ve found in tens of thousands of outreach conversations, for example, that direct assertions of my beliefs, even when they seem to contradict what another person believes, are extraordinary effective so long as I assert them in a way that shows care for the people I’m talking to. Too often, instead, our disagreements are argumentative, and we assume the worst in the people we’re talking to, rather than the best. Here’s an example of what can happen when we do the opposite of that.

Lesson 3: Demand collective transparency. But it’s not enough to find the truth, and share it, if the institutions around us aren’t changing. Any individual effort to challenge corporate or political deception will be like trying to run headfirst into a tidal wave, unless we can change the systems that are driving these lies. And while there are many worthwhile efforts to stop systemic deception, the most important of them is transparency.

This is why the Big Meat industry, for example, has exerted so much effort passing ag gag laws across the nation, which prohibit photographs in factory farms. It is why they use false “biosecurity” claims to prevent any visitors on their farms, making food production facilities arguably more secretive than labs that study possible bioweapons. And it is why the industry has used its political influence to induce the government and law enforcement to behave in ways that resemble comic book villainy – e.g., chasing after piglets across state lines – to cover up their crimes. They know that, if transparency rather than secrecy become the norm, it will create change.

This is why what will unfold at trial in September, where I and my co-defendant Paul Picklesimer face trumped up charges of burglary and theft for an investigation and open rescue at the largest pig farm in the world, affects all of us. While Smithfield is nominally targeting Paul and I, their real target is transparency and truth. They don’t want the world to know they continue to raise mother pigs in tortuous crates; that baby pigs are flailing and screaming in pools of blood and feces; and that the industry’s marketing (“Good Food. Responsibly Raised.”) is a sham. Their business model, like so much of power in the modern world, depends on a lie.

And if they are able to punish and imprison dissenters who point out these lies, it’s not just Paul and I who will suffer. The movement for transparency and truth will suffer, too.

—

So what’s the upshot? We are in a moment of unprecedented deception and distrust. But that makes it even more important that each of us, both individually and in our collective action, strive to challenge lies with truth. We should be looking for proof, rather than believing the things we see and hear. We should be radically candid in sharing that truth. And we should be demanding collective transparency, especially when powerful forces are trying to impose secrecy by punishing those who are shining light in places that are hidden in the dark.

If we do those things, the promise of Upton Sinclair’s muckraking, 100 years ago, will be fulfilled. We’ll have a truly safe and humane system of meat production, including a system of meat that is entirely plant-based.

But we’ll have much more, too, including a society that can survive the conflict and disconnection that is destroying our entire planet.

—

Now on to the notes for the week!

As usual, we’ll be hosting a Friday Night Hangout on the subject of this blog – with a presentation by Priya Sawhney. But since I’m traveling today, Priya Sawhney will share some lessons she’s learned, on how to stop lying, and we’ll have a Zoom for anyone who wants to join remotely! Here’s the in-person event page. Respond to this email if you’d like to be added to the chat where that Zoom link will be distributed.

Speaking of traveling, I’m speaking at the International Vegan Film Festival in Fort Lauderdale tomorrow (Saturday, July 30) at 11:10 am ET (8:10 am PT), then joining a panel at 2:20 pm ET (11:20 am PT). There are going to be some amazing films and presenters, and I’d love to see you there if you happen to be in Florida!

This is the week we’re making a big push for media of all sorts for the Smithfield trial, so let us know if you have contacts. I’ve already had some great conversations with podcast producers, documentary makers and journalists – all of whom have been stunned by the bizarre story of our investigation and rescue at the largest pig farm in the nation. But to ensure we achieve the highest impact at trial, we need your help. If you know of a podcast that might have me on, a journalist who might write about the trial, or an influencer who might be willing to amplify our message and support the right to rescue, let me know. We have just over one month to prepare, so time is of the essence!

Heading to Chicago and Colorado, to see some important people and places before trial. Many of you know that I don’t take vacations often. And when I do, they usually relate to the animals. And that will be partially true of my travel next week. I’m heading to Colorado to hang out at Luvin’ Arms, the sanctuary that was raided by the FBI in search of two baby pigs. But I’m also going back to Chicago, to visit some of my old stomping grounds one last time before I head to trial in September. If you’re in Chicago or Colorado, and would like to hang out, let me know!

What do you want to hear about next week, in this blog and at the Friday Night Hangout? Here’s the survey. Take one minute to fill this out. It really helps to get your thoughts!

Thanks for reading, everyone!

If you liked this post from The Simple Heart, why not share it?