| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Gene Editing Gone Wrong: Scientists Accidentally Create Angry Hamsters |

| Date | June 20, 2022 12:05 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[For 40 years, scientists thought a specific gene was linked to

aggression in hamsters. Removing it, however, had violent

consequences.]

[[link removed]]

GENE EDITING GONE WRONG: SCIENTISTS ACCIDENTALLY CREATE ANGRY

HAMSTERS

[[link removed]]

Peter Rogers

June 16, 2022

Big Think [[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ For 40 years, scientists thought a specific gene was linked to

aggression in hamsters. Removing it, however, had violent

consequences. _

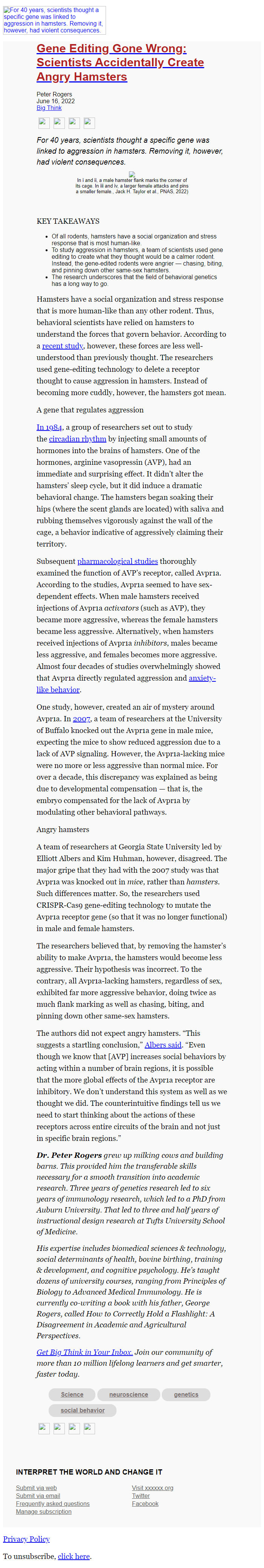

In i and ii, a male hamster flank marks the corner of its cage. In

iii and iv, a larger female attacks and pins a smaller female., Jack

H. Taylor et al., PNAS, 2022)

KEY TAKEAWAYS

* Of all rodents, hamsters have a social organization and stress

response that is most human-like.

* To study aggression in hamsters, a team of scientists used gene

editing to create what they thought would be a calmer rodent. Instead,

the gene-edited rodents were angrier — chasing, biting, and pinning

down other same-sex hamsters.

* The research underscores that the field of behavioral genetics has

a long way to go.

Hamsters have a social organization and stress response that is more

human-like than any other rodent. Thus, behavioral scientists have

relied on hamsters to understand the forces that govern behavior.

According to a recent study

[[link removed]], however, these

forces are less well-understood than previously thought. The

researchers used gene-editing technology to delete a receptor thought

to cause aggression in hamsters. Instead of becoming more cuddly,

however, the hamsters got mean.

A gene that regulates aggression

In 1984

[[link removed]],

a group of researchers set out to study the circadian rhythm

[[link removed]] by injecting

small amounts of hormones into the brains of hamsters. One of the

hormones, arginine vasopressin (AVP), had an immediate and surprising

effect. It didn’t alter the hamsters’ sleep cycle, but it did

induce a dramatic behavioral change. The hamsters began soaking their

hips (where the scent glands are located) with saliva and rubbing

themselves vigorously against the wall of the cage, a behavior

indicative of aggressively claiming their territory.

Subsequent pharmacological studies

[[link removed]] thoroughly

examined the function of AVP’s receptor, called Avpr1a. According to

the studies, Avpr1a seemed to have sex-dependent effects. When male

hamsters received injections of Avpr1a _activators _(such as AVP),

they became more aggressive, whereas the female hamsters became less

aggressive. Alternatively, when hamsters received injections of

Avpr1a _inhibitors_, males became less aggressive, and females

becomes more aggressive. Almost four decades of studies overwhelmingly

showed that Avpr1a directly regulated aggression and anxiety-like

behavior [[link removed]].

One study, however, created an air of mystery around Avpr1a. In 2007

[[link removed]],

a team of researchers at the University of Buffalo knocked out the

Avpr1a gene in male mice, expecting the mice to show reduced

aggression due to a lack of AVP signaling. However, the Avpr1a-lacking

mice were no more or less aggressive than normal mice. For over a

decade, this discrepancy was explained as being due to developmental

compensation — that is, the embryo compensated for the lack of

Avpr1a by modulating other behavioral pathways.

Angry hamsters

A team of researchers at Georgia State University led by Elliott

Albers and Kim Huhman, however, disagreed. The major gripe that they

had with the 2007 study was that Avpr1a was knocked out in _mice_,

rather than _hamsters_. Such differences matter. So, the researchers

used CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to mutate the Avpr1a receptor

gene (so that it was no longer functional) in male and female

hamsters.

The researchers believed that, by removing the hamster’s ability to

make Avpr1a, the hamsters would become less aggressive. Their

hypothesis was incorrect. To the contrary, all Avpr1a-lacking

hamsters, regardless of sex, exhibited far more aggressive behavior,

doing twice as much flank marking as well as chasing, biting, and

pinning down other same-sex hamsters.

The authors did not expect angry hamsters. “This suggests a

startling conclusion,” Albers said

[[link removed]].

“Even though we know that [AVP] increases social behaviors by acting

within a number of brain regions, it is possible that the more global

effects of the Avpr1a receptor are inhibitory. We don’t understand

this system as well as we thought we did. The counterintuitive

findings tell us we need to start thinking about the actions of these

receptors across entire circuits of the brain and not just in specific

brain regions.”

_DR. PETER ROGERS grew up milking cows and building barns. This

provided him the transferable skills necessary for a smooth transition

into academic research. Three years of genetics research led to six

years of immunology research, which led to a PhD from Auburn

University. That led to three and half years of instructional design

research at Tufts University School of Medicine._

_His expertise includes biomedical sciences & technology, social

determinants of health, bovine birthing, training & development, and

cognitive psychology. He’s taught dozens of university courses,

ranging from Principles of Biology to Advanced Medical Immunology. He

is currently co-writing a book with his father, George Rogers,

called How to Correctly Hold a Flashlight: A Disagreement in Academic

and Agricultural Perspectives._

_Get Big Think in Your Inbox. [[link removed]] Join

our community of more than 10 million lifelong learners and get

smarter, faster today._

* Science

[[link removed]]

* neuroscience

[[link removed]]

* genetics

[[link removed]]

* social behavior

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

aggression in hamsters. Removing it, however, had violent

consequences.]

[[link removed]]

GENE EDITING GONE WRONG: SCIENTISTS ACCIDENTALLY CREATE ANGRY

HAMSTERS

[[link removed]]

Peter Rogers

June 16, 2022

Big Think [[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ For 40 years, scientists thought a specific gene was linked to

aggression in hamsters. Removing it, however, had violent

consequences. _

In i and ii, a male hamster flank marks the corner of its cage. In

iii and iv, a larger female attacks and pins a smaller female., Jack

H. Taylor et al., PNAS, 2022)

KEY TAKEAWAYS

* Of all rodents, hamsters have a social organization and stress

response that is most human-like.

* To study aggression in hamsters, a team of scientists used gene

editing to create what they thought would be a calmer rodent. Instead,

the gene-edited rodents were angrier — chasing, biting, and pinning

down other same-sex hamsters.

* The research underscores that the field of behavioral genetics has

a long way to go.

Hamsters have a social organization and stress response that is more

human-like than any other rodent. Thus, behavioral scientists have

relied on hamsters to understand the forces that govern behavior.

According to a recent study

[[link removed]], however, these

forces are less well-understood than previously thought. The

researchers used gene-editing technology to delete a receptor thought

to cause aggression in hamsters. Instead of becoming more cuddly,

however, the hamsters got mean.

A gene that regulates aggression

In 1984

[[link removed]],

a group of researchers set out to study the circadian rhythm

[[link removed]] by injecting

small amounts of hormones into the brains of hamsters. One of the

hormones, arginine vasopressin (AVP), had an immediate and surprising

effect. It didn’t alter the hamsters’ sleep cycle, but it did

induce a dramatic behavioral change. The hamsters began soaking their

hips (where the scent glands are located) with saliva and rubbing

themselves vigorously against the wall of the cage, a behavior

indicative of aggressively claiming their territory.

Subsequent pharmacological studies

[[link removed]] thoroughly

examined the function of AVP’s receptor, called Avpr1a. According to

the studies, Avpr1a seemed to have sex-dependent effects. When male

hamsters received injections of Avpr1a _activators _(such as AVP),

they became more aggressive, whereas the female hamsters became less

aggressive. Alternatively, when hamsters received injections of

Avpr1a _inhibitors_, males became less aggressive, and females

becomes more aggressive. Almost four decades of studies overwhelmingly

showed that Avpr1a directly regulated aggression and anxiety-like

behavior [[link removed]].

One study, however, created an air of mystery around Avpr1a. In 2007

[[link removed]],

a team of researchers at the University of Buffalo knocked out the

Avpr1a gene in male mice, expecting the mice to show reduced

aggression due to a lack of AVP signaling. However, the Avpr1a-lacking

mice were no more or less aggressive than normal mice. For over a

decade, this discrepancy was explained as being due to developmental

compensation — that is, the embryo compensated for the lack of

Avpr1a by modulating other behavioral pathways.

Angry hamsters

A team of researchers at Georgia State University led by Elliott

Albers and Kim Huhman, however, disagreed. The major gripe that they

had with the 2007 study was that Avpr1a was knocked out in _mice_,

rather than _hamsters_. Such differences matter. So, the researchers

used CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to mutate the Avpr1a receptor

gene (so that it was no longer functional) in male and female

hamsters.

The researchers believed that, by removing the hamster’s ability to

make Avpr1a, the hamsters would become less aggressive. Their

hypothesis was incorrect. To the contrary, all Avpr1a-lacking

hamsters, regardless of sex, exhibited far more aggressive behavior,

doing twice as much flank marking as well as chasing, biting, and

pinning down other same-sex hamsters.

The authors did not expect angry hamsters. “This suggests a

startling conclusion,” Albers said

[[link removed]].

“Even though we know that [AVP] increases social behaviors by acting

within a number of brain regions, it is possible that the more global

effects of the Avpr1a receptor are inhibitory. We don’t understand

this system as well as we thought we did. The counterintuitive

findings tell us we need to start thinking about the actions of these

receptors across entire circuits of the brain and not just in specific

brain regions.”

_DR. PETER ROGERS grew up milking cows and building barns. This

provided him the transferable skills necessary for a smooth transition

into academic research. Three years of genetics research led to six

years of immunology research, which led to a PhD from Auburn

University. That led to three and half years of instructional design

research at Tufts University School of Medicine._

_His expertise includes biomedical sciences & technology, social

determinants of health, bovine birthing, training & development, and

cognitive psychology. He’s taught dozens of university courses,

ranging from Principles of Biology to Advanced Medical Immunology. He

is currently co-writing a book with his father, George Rogers,

called How to Correctly Hold a Flashlight: A Disagreement in Academic

and Agricultural Perspectives._

_Get Big Think in Your Inbox. [[link removed]] Join

our community of more than 10 million lifelong learners and get

smarter, faster today._

* Science

[[link removed]]

* neuroscience

[[link removed]]

* genetics

[[link removed]]

* social behavior

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV