| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | How devaluing friendship became my biggest mistake (Podcast) |

| Date | May 19, 2022 4:17 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

In January 2016, three years into launching a grassroots animal rights network called Direct Action Everywhere, I got, what felt to me, like the opportunity of a lifetime: a conversation with Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam. While not famous outside of academia, Doug is a towering figure within the scholarship of social movements, inventing important concepts (such as cognitive liberation [ [link removed] ],) and igniting entire waves of social movement research (like political opportunity theory [ [link removed] ]) that have changed the way people think about creating change.

Listen to the conversation I had with Doug on the Green Pill podcast. [ [link removed] ]

I was particularly interested in talking to Doug, however, for a very personal reason: a study he performed played a significant role in transforming my life. I was an intensely-isolated human being [ [link removed] ] in the early 2000s, focused almost entirely on my academic work [ [link removed] ], when I was first exposed to research by Doug (and by fellow sociologist Duncan Watts [ [link removed] ]), on the importance of networks to social change. Duncan’s mathematically-elegant work [ [link removed] ] provided a theoretical foundation for the importance of social networks to change. Human social networks have a strange mathematical property, which allows every node in the network, i.e., every individual human being, to be connected to every other node by a mere 6 degrees of separation [ [link removed] ]. Importantly, this remains true no matter how large the total number of nodes/human beings, which allows change to spread rapidly throughout the network, even as the human population reaches 8 billion.

But it was Doug’s gritty empirical work — diving deeply into archives at the King Center to identify trends in data — that led to perhaps the the most important insight into how social networks actually drive change. And in one word, what Doug found was that change happens in part through something very simple:

Friendship.

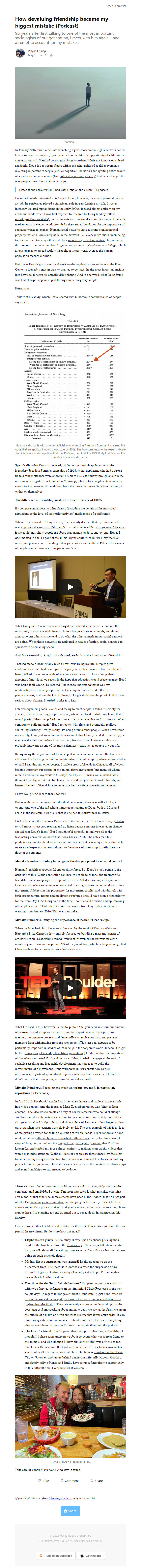

Table 9 of his study, which I have shared with hundreds if not thousands of people, says it all.

Specifically, what Doug discovered, while poring through applications to the legendary Freedom Summer campaign of 1964 [ [link removed] ], is that applicants who had a strong tie to a fellow attendee were about 60.4% more likely to follow through and join the movement to register Black voters in Mississippi. In contrast, applicants who had a strong tie to someone who withdrew from the movement were 39.5% more likely to withdraw themselves.

The difference in friendship, in short, was a difference of 100%.

By comparison, almost no other factors (including the beliefs of the individual applicants, or the level of their prior activism) made much of a difference.

When I first learned of Doug’s work, I had already decided that my mission in life was to protect the animals of this earth [ [link removed] ]. I naively believed that change would be easy [ [link removed] ], if we could only show people the abuse that animals endure, one-by-one. But as I documented in a talk I gave at the animal rights conference in 2014, my focus on individual persuasion — handing out vegan cookies and leaflets/DVDs to thousands of people over a three-year time period — failed.

What Doug and Duncan’s research taught me is that it’s the network, and not the individual, that creates real change. Human beings are social animals, and though almost no one admits it, we tend to do what the other animals in our social network are doing. When those networks are activated in waves of action, social change can spread with astonishing speed.

And those networks, Doug’s work showed, are built on the foundation of friendship.

That led me to fundamentally revisit how I was living my life. Despite great academic success, I had never gone to a party, never been inside a bar or club, and barely talked to anyone outside of academics and activism. I was doing absurd amounts of individual outreach, in the hope that education would create change. But I was doing it all wrong. To succeed, I needed to understand that it was my relationships with other people, and not just my individual work ethic or persuasiveness, that was the key to change. Doug’s study was the proof. And if I was serious about change, I needed to take it to heart.

I started organizing social events and trying to meet people. I failed miserably for years. (I remember telling people early on, when they tried to shake my hand, that I would prefer if they just poked me from a safe distance with a stick. It wasn’t the best community-building tactic.) But I got better with time, and eventually realized something startling: I really, really like being around other people. When I overcame my anxiety, I enjoyed social interaction so much that I barely needed to eat, sleep, or even use the bathroom when I was with my friends. If you know me today, you probably know me as one of the most relentlessly extroverted people in your life.

Recognizing the importance of friendship also made me much more effective as an advocate. By focusing on building relationships, I could amplify whatever knowledge or skill I had through other people. I made a crew of friends in Chicago, all of whom became important supporters of the animal rights movement (and many of whom remain involved in my work to this day). And by 2013, when we launched DxE, I thought I had figured it out. To change the world, we just had to make friends, and harness the ties of friendships to serve as a bedrock for a powerful movement.

I have Doug McAdam to thank for that.

But as with my naive views on individual persuasion, there was still a lot I got wrong. And one of the refreshing things about talking to Doug, both in 2016 and again in the last couple weeks, is that it’s helped to clarify those mistakes.

I talk a bit about the mistakes I’ve made in the podcast. (If you haven’t yet, go listen to it [ [link removed] ]. Seriously, just stop reading and go listen because anyone interested in change should hear Doug’s ideas.) But I thought it’d be useful to link you all to the fascinating conversation notes [ [link removed] ] that I took back in 2016. The notes read like predictions come to life. And while each of these mistakes is unique, they also each relate to a deeper misunderstanding into the nature of friendship. Briefly, here are three of the big ones:

Mistake Number 1. Failing to recognize the dangers posed by internal conflict.

Human friendship is a powerful and positive force. But Doug’s study points to the dark side of this. While connection can inspire people to change, the fracture of a friendship can cause people to drop out, with a 39.5% decrease in participation in Doug’s study when someone was connected to a single person who withdrew from a movement. Addressing this propensity for movement conflict and withdrawal, with both strong cultural norms and mediation structures, should have been a high priority for me from Day 1. As Doug said at the time, “conflict and division end up ‘blowing off people’s arms.’ ” But I didn’t make it a priority from Day 1, despite Doug’s warning from January 2016. That was a mistake.

Mistake Number 2. Denying the importance of (scalable) leadership.

When we launched DxE, I was — influenced by the work of Duncan Watts and Harvard’s Erica Chenoweth [ [link removed] ] — entirely focused on building a mass movement of ordinary people. Leadership seemed irrelevant. Movement power was strictly a numbers game: how we do get to 3.5% of the population, which is the percentage that Chenoweth set for a movement to achieve success.

What I missed in this, however, is that to get to 3.5%, you need an enormous amount of grassroots leadership, or the entire thing falls apart. You need people to run meetings, to organize protests, and (especially) to resolve conflicts and prevent members from withdrawing from the movement. (This last goal appears to be particularly important in studies of leadership in the corporate world [ [link removed] ]. Indeed, it might be the primary way leadership benefits organizations [ [link removed] ].) I didn’t realize the importance of this when we started DxE, and because of that, I failed to engage in the sort of scalable recruiting and leadership development that’s needed to build the infrastructure of a movement. Doug warned us in 2016 about how Leftist movements, in particular, are afraid of power in a way that causes them to fail; I didn’t realize that I was going to make that mistake myself.

Mistake Number 3. Focusing too much on technology (and, in particular, algorithms on Facebook).

In April 2016, Facebook launched its Live video feature and made a massive push into video content. And the focus, as Mark Zuckerberg put it [ [link removed] ], was “shorter form content.” The idea was to create an army of content creators who could challenge YouTube and draw the nation’s attention to Facebook. We immediately noticed the change in Facebook’s algorithms, and short videos of 1 minute or less began to blow up, even when their content was relatively trivial. The best example of this is a video of me getting arrested for asking a question at Whole Foods. I spent about one hour on it, and it was ultimately viewed nearly 4 million times [ [link removed] ]. Partly for this reason, I stopped blogging, or making the longer form [ [link removed] ], participatory content [ [link removed] ] that DxE was known for, and shifted my focus almost entirely to making short [ [link removed] ] catchy [ [link removed] ] videos that would maximize attention. While millions of people saw these videos, by focusing too much of my energy on attention for its own sake, I would lose focus on building power through organizing. The real, face-to-face work — the creation of relationships and even friendships — still needed to be done.

—

There are a lot of other mistakes I could point to (and that Doug did point to in the conversation from 2016). But what I’m most interested is what mistakes you think I’ve made, or that other social movements have been made. Indeed, that’s a huge part of why I’m launching a new initiative [ [link removed] ] and stepping back from my roles at DxE: to correct some of my prior mistakes. So if you’re interested in that conversation, please sign up here [ [link removed] ]. I’m planning to send an email out to schedule an initial meeting this Sunday.

Here are some other hot takes and updates for the week. (I want to start doing this, as part of the newsletter. But let’s see how this goes!)

Elephants can grieve. A new study shows Asian elephants grieving their dead for the first time. From the Times story [ [link removed] ]: “We always talk about habitat loss, we talk about all these things. We are not talking about what animals are going through psychologically.”

My law license suspension was vacated! Really good news on the disbarment front. The State Bar Court has vacated the suspension of my license! I’ll go live to discuss today (Thursday) at 2:30 pm PT and update here with a link after it’s done.

Questions for the Smithfield defendants? I’m planning to have a podcast with two of my co-defendants in the Smithfield Circle Four case in the next couple days, in regard to our government’s multistate “piglet hunt” after we exposed abuses at the largest pig farm in the world, and rescued two dying piglets from the facility [ [link removed] ]. The state recently succeeded in demanding that the court gag us from speaking about animal cruelty we saw at the farm; we are in the middle of a make-or-break appeal to reverse that lower court order. If you have any questions or comments — about Smithfield, the case, or anything else — send them my way, as I’d love to integrate them into the podcast.

The loss of a friend. Finally, given that the topic of this blog is friendship, I thought I’d share some tragic news about someone who was a great friend to the animals, and who (though I knew him only briefly) was a friend to me, too: Trevor Bellaccomo. It’s hard to even believe this, as Trevor was such a kind soul in all my interactions with him. But he was murdered in Salt Lake City on Saturday [ [link removed] ], and leaves behind a grieving wife, Ally Kiyomi Goddard, and family. Ally’s friends and family have set up a fundraiser [ [link removed] ] to support Ally in this difficult time. Contribute what you can.

Take care of yourself, everyone. And stay in touch.

Unsubscribe [link removed]

In January 2016, three years into launching a grassroots animal rights network called Direct Action Everywhere, I got, what felt to me, like the opportunity of a lifetime: a conversation with Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam. While not famous outside of academia, Doug is a towering figure within the scholarship of social movements, inventing important concepts (such as cognitive liberation [ [link removed] ],) and igniting entire waves of social movement research (like political opportunity theory [ [link removed] ]) that have changed the way people think about creating change.

Listen to the conversation I had with Doug on the Green Pill podcast. [ [link removed] ]

I was particularly interested in talking to Doug, however, for a very personal reason: a study he performed played a significant role in transforming my life. I was an intensely-isolated human being [ [link removed] ] in the early 2000s, focused almost entirely on my academic work [ [link removed] ], when I was first exposed to research by Doug (and by fellow sociologist Duncan Watts [ [link removed] ]), on the importance of networks to social change. Duncan’s mathematically-elegant work [ [link removed] ] provided a theoretical foundation for the importance of social networks to change. Human social networks have a strange mathematical property, which allows every node in the network, i.e., every individual human being, to be connected to every other node by a mere 6 degrees of separation [ [link removed] ]. Importantly, this remains true no matter how large the total number of nodes/human beings, which allows change to spread rapidly throughout the network, even as the human population reaches 8 billion.

But it was Doug’s gritty empirical work — diving deeply into archives at the King Center to identify trends in data — that led to perhaps the the most important insight into how social networks actually drive change. And in one word, what Doug found was that change happens in part through something very simple:

Friendship.

Table 9 of his study, which I have shared with hundreds if not thousands of people, says it all.

Specifically, what Doug discovered, while poring through applications to the legendary Freedom Summer campaign of 1964 [ [link removed] ], is that applicants who had a strong tie to a fellow attendee were about 60.4% more likely to follow through and join the movement to register Black voters in Mississippi. In contrast, applicants who had a strong tie to someone who withdrew from the movement were 39.5% more likely to withdraw themselves.

The difference in friendship, in short, was a difference of 100%.

By comparison, almost no other factors (including the beliefs of the individual applicants, or the level of their prior activism) made much of a difference.

When I first learned of Doug’s work, I had already decided that my mission in life was to protect the animals of this earth [ [link removed] ]. I naively believed that change would be easy [ [link removed] ], if we could only show people the abuse that animals endure, one-by-one. But as I documented in a talk I gave at the animal rights conference in 2014, my focus on individual persuasion — handing out vegan cookies and leaflets/DVDs to thousands of people over a three-year time period — failed.

What Doug and Duncan’s research taught me is that it’s the network, and not the individual, that creates real change. Human beings are social animals, and though almost no one admits it, we tend to do what the other animals in our social network are doing. When those networks are activated in waves of action, social change can spread with astonishing speed.

And those networks, Doug’s work showed, are built on the foundation of friendship.

That led me to fundamentally revisit how I was living my life. Despite great academic success, I had never gone to a party, never been inside a bar or club, and barely talked to anyone outside of academics and activism. I was doing absurd amounts of individual outreach, in the hope that education would create change. But I was doing it all wrong. To succeed, I needed to understand that it was my relationships with other people, and not just my individual work ethic or persuasiveness, that was the key to change. Doug’s study was the proof. And if I was serious about change, I needed to take it to heart.

I started organizing social events and trying to meet people. I failed miserably for years. (I remember telling people early on, when they tried to shake my hand, that I would prefer if they just poked me from a safe distance with a stick. It wasn’t the best community-building tactic.) But I got better with time, and eventually realized something startling: I really, really like being around other people. When I overcame my anxiety, I enjoyed social interaction so much that I barely needed to eat, sleep, or even use the bathroom when I was with my friends. If you know me today, you probably know me as one of the most relentlessly extroverted people in your life.

Recognizing the importance of friendship also made me much more effective as an advocate. By focusing on building relationships, I could amplify whatever knowledge or skill I had through other people. I made a crew of friends in Chicago, all of whom became important supporters of the animal rights movement (and many of whom remain involved in my work to this day). And by 2013, when we launched DxE, I thought I had figured it out. To change the world, we just had to make friends, and harness the ties of friendships to serve as a bedrock for a powerful movement.

I have Doug McAdam to thank for that.

But as with my naive views on individual persuasion, there was still a lot I got wrong. And one of the refreshing things about talking to Doug, both in 2016 and again in the last couple weeks, is that it’s helped to clarify those mistakes.

I talk a bit about the mistakes I’ve made in the podcast. (If you haven’t yet, go listen to it [ [link removed] ]. Seriously, just stop reading and go listen because anyone interested in change should hear Doug’s ideas.) But I thought it’d be useful to link you all to the fascinating conversation notes [ [link removed] ] that I took back in 2016. The notes read like predictions come to life. And while each of these mistakes is unique, they also each relate to a deeper misunderstanding into the nature of friendship. Briefly, here are three of the big ones:

Mistake Number 1. Failing to recognize the dangers posed by internal conflict.

Human friendship is a powerful and positive force. But Doug’s study points to the dark side of this. While connection can inspire people to change, the fracture of a friendship can cause people to drop out, with a 39.5% decrease in participation in Doug’s study when someone was connected to a single person who withdrew from a movement. Addressing this propensity for movement conflict and withdrawal, with both strong cultural norms and mediation structures, should have been a high priority for me from Day 1. As Doug said at the time, “conflict and division end up ‘blowing off people’s arms.’ ” But I didn’t make it a priority from Day 1, despite Doug’s warning from January 2016. That was a mistake.

Mistake Number 2. Denying the importance of (scalable) leadership.

When we launched DxE, I was — influenced by the work of Duncan Watts and Harvard’s Erica Chenoweth [ [link removed] ] — entirely focused on building a mass movement of ordinary people. Leadership seemed irrelevant. Movement power was strictly a numbers game: how we do get to 3.5% of the population, which is the percentage that Chenoweth set for a movement to achieve success.

What I missed in this, however, is that to get to 3.5%, you need an enormous amount of grassroots leadership, or the entire thing falls apart. You need people to run meetings, to organize protests, and (especially) to resolve conflicts and prevent members from withdrawing from the movement. (This last goal appears to be particularly important in studies of leadership in the corporate world [ [link removed] ]. Indeed, it might be the primary way leadership benefits organizations [ [link removed] ].) I didn’t realize the importance of this when we started DxE, and because of that, I failed to engage in the sort of scalable recruiting and leadership development that’s needed to build the infrastructure of a movement. Doug warned us in 2016 about how Leftist movements, in particular, are afraid of power in a way that causes them to fail; I didn’t realize that I was going to make that mistake myself.

Mistake Number 3. Focusing too much on technology (and, in particular, algorithms on Facebook).

In April 2016, Facebook launched its Live video feature and made a massive push into video content. And the focus, as Mark Zuckerberg put it [ [link removed] ], was “shorter form content.” The idea was to create an army of content creators who could challenge YouTube and draw the nation’s attention to Facebook. We immediately noticed the change in Facebook’s algorithms, and short videos of 1 minute or less began to blow up, even when their content was relatively trivial. The best example of this is a video of me getting arrested for asking a question at Whole Foods. I spent about one hour on it, and it was ultimately viewed nearly 4 million times [ [link removed] ]. Partly for this reason, I stopped blogging, or making the longer form [ [link removed] ], participatory content [ [link removed] ] that DxE was known for, and shifted my focus almost entirely to making short [ [link removed] ] catchy [ [link removed] ] videos that would maximize attention. While millions of people saw these videos, by focusing too much of my energy on attention for its own sake, I would lose focus on building power through organizing. The real, face-to-face work — the creation of relationships and even friendships — still needed to be done.

—

There are a lot of other mistakes I could point to (and that Doug did point to in the conversation from 2016). But what I’m most interested is what mistakes you think I’ve made, or that other social movements have been made. Indeed, that’s a huge part of why I’m launching a new initiative [ [link removed] ] and stepping back from my roles at DxE: to correct some of my prior mistakes. So if you’re interested in that conversation, please sign up here [ [link removed] ]. I’m planning to send an email out to schedule an initial meeting this Sunday.

Here are some other hot takes and updates for the week. (I want to start doing this, as part of the newsletter. But let’s see how this goes!)

Elephants can grieve. A new study shows Asian elephants grieving their dead for the first time. From the Times story [ [link removed] ]: “We always talk about habitat loss, we talk about all these things. We are not talking about what animals are going through psychologically.”

My law license suspension was vacated! Really good news on the disbarment front. The State Bar Court has vacated the suspension of my license! I’ll go live to discuss today (Thursday) at 2:30 pm PT and update here with a link after it’s done.

Questions for the Smithfield defendants? I’m planning to have a podcast with two of my co-defendants in the Smithfield Circle Four case in the next couple days, in regard to our government’s multistate “piglet hunt” after we exposed abuses at the largest pig farm in the world, and rescued two dying piglets from the facility [ [link removed] ]. The state recently succeeded in demanding that the court gag us from speaking about animal cruelty we saw at the farm; we are in the middle of a make-or-break appeal to reverse that lower court order. If you have any questions or comments — about Smithfield, the case, or anything else — send them my way, as I’d love to integrate them into the podcast.

The loss of a friend. Finally, given that the topic of this blog is friendship, I thought I’d share some tragic news about someone who was a great friend to the animals, and who (though I knew him only briefly) was a friend to me, too: Trevor Bellaccomo. It’s hard to even believe this, as Trevor was such a kind soul in all my interactions with him. But he was murdered in Salt Lake City on Saturday [ [link removed] ], and leaves behind a grieving wife, Ally Kiyomi Goddard, and family. Ally’s friends and family have set up a fundraiser [ [link removed] ] to support Ally in this difficult time. Contribute what you can.

Take care of yourself, everyone. And stay in touch.

Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Substack