May 13, 2022

Permission to republish original opeds and cartoons granted.

Biden promises to boost U.S. wheat production to combat loss of Ukrainian, Russian wheat exports, but production here is down 15 percent since 2019

By Robert Romano

President Joe Biden is promising to boost U.S. production of wheat to offset the loss of Ukrainian and Russian exports from the Black Sea thanks to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that has shut down the ports there, stating at a farm in Illinois on May 11 that he would extend crop insurance for farmers who double crop in a bid to get more wheat to market this year.

Already, the global shortfall is 4.5 million tons this year, so far, according to the latest data by the Department of Agriculture: “Global production is forecast at 774.8 million tons, 4.5 million lower than in 2021/22. Reduced production in Ukraine, Australia, and Morocco is only partly offset by increases in Canada, Russia, and the United States. Production in Ukraine is forecast at 21.5 million tons in 2022/23, 11.5 million lower than 2021/22 due to the ongoing war.

Biden warned that Ukraine cannot move its current winter wheat crop out to markets, consisting of 20 million tons, without which could trigger starvation in the third world: “Ukraine says they have 20 million tons of grain in their silos right now — 20 million tons. And guess what? If those tons don’t get to market, an awful lot of people in Africa are going to starve to death because they are the sole — sole supplier of a number of African countries.”

The problem is Russia’s blockade of Ukraine’s ports, Biden said: “[B]ecause of what the Russians are doing in the Black Sea, Putin has warships — battleships preventing the access to Ukrainian ports to get this — this grain out, to get this wheat out. The brutal war launched on Ukrainian soil has prevented Ukrainian farmers from planting next year’s crop and next year’s harvest.”

Meaning the shortfalls will conceivably last as long as the war in Ukraine lasts. The problem is that the war in Ukraine has been going on since 2014 after former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was removed from power as Russia annexed Crimea and the war in the eastern Donbass region began. Now with both sides digging in for more fighting, a stalemate appears to be worst possible outcome.

But will Biden’s plan even work? U.S. wheat production is down 15 percent since 2019, from 1.93 billion bushels in 2019 to 1.64 billion in 2021, according to data compiled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Overall, the U.S. produces a little more than half of what it did in 1981, when it produced more than 75 million metric tons. That was down to 44.8 million in 2021.

The domestic wheat shortfall last year was thanks to major drought conditions that severely impacted production in Idaho, Montana and North Dakota, another hit to global food production that could not come at a worse time.

The biggest part of the problem is not enough has been planted. According to a March Department of Agriculture release on prospective plantings, 2022 will be the fifth lowest area planted since 1919: “All wheat planted area for 2022 is estimated at 47.4 million acres, up 1 percent from 2021. If realized, this represents the fifth lowest all wheat planted area since records began in 1919.”

Is Biden’s crop insurance program enough to avert potential starvation in the third world and beyond?

Given current conditions — Biden also complained in his speech that the spring had been very cool this year and that there was less time to plant more wheat this year — it appears unlikely the U.S. will be able to boost production to even get back to 2019 levels, let alone to offset drops in Ukrainian and Russian exports. Meaning, the worst may be yet to come.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

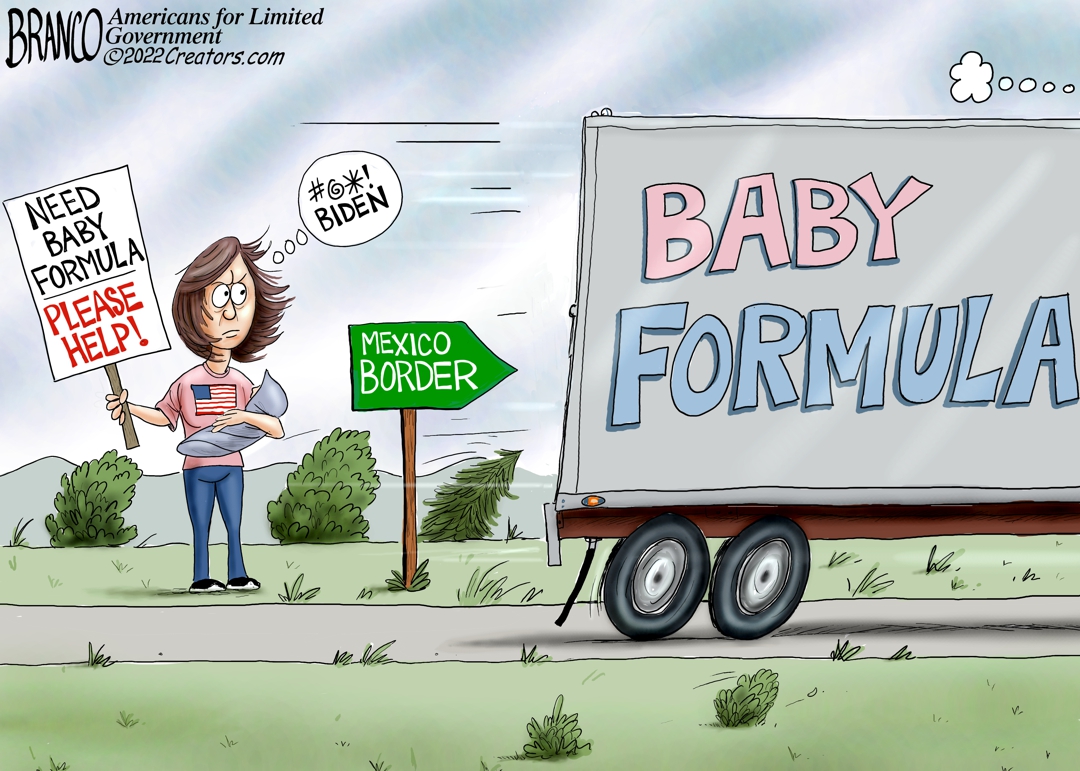

Cartoon: The Hunger Games

By A.F. Branco

Click here for a higher-level resolution version.

ALG Editor’s Note: In the following featured report from Breitbart.com’s John Carney, the Producer Price Index reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics grew at 11 percent annualized in April:

John Carney: Bad News and Worse News on Inflation

By John Carney

The bad news is that Thursday’s April producer price inflation figures showed that inflation had not cooled by as much as expected, just as the consumer price inflation figures had a day earlier.

The worse news is that by some measures inflation did not cool at all. In fact, in some of the metrics most salient to Americans, inflation picked up in April.

The Department of Labor’s Producer Price Index (PPI) indicated that prices of goods and services produced by U.S. businesses were up 11 percent compared with last year. That is the fifth consecutive month of double-digit annual price gains picked up by this gauge. Economists had forecast an even steeper decline to 10.7 percent.

In an unusual twist, the annual number came in worse than expected even though the monthly number was right on target at 0.5 percent. How could the year-over-year number register higher if the month-over-month number was on target? The answer is that the March figures were revised upward, indicating that inflation was already stronger than expected. March’s gain over February originally reported at 1.4 percent now stands at 1.6 percent. The February report was revised up from a 0.9 percent gain to 1.1 percent.

The upward revisions compound. A $1,000 widget that goes through the unrevised inflation figures comes out at $1,028.24, a three-month gain of 2.82 percent. The revised figures bring the price up to $1,032.32, a 3.23 cumulative three-month gain. That’s a little more than a 0.4 percent difference, which is why we wound up with 11 percent instead of 10.7 percent despite the as-expected monthly figure. To put it slightly differently, yes, prices rose by 0.5 percent, but they rose off a higher base, which means that prices are actually higher than forecast.

Now might be a good time to explain what the Producer Price Index (PPI) is and how it differs from its more famous cousin, the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Both are measures of the average price changes of a large basket of goods and services. The CPI measures prices from the perspective of consumers. That means it excludes sales to government or to businesses for product inputs and capital investment. It also includes imports and sales taxes, which are paid for by consumers, but not exports, which are not paid for by U.S. consumers.

The PPI, on the other hand, measures prices from the perspective of businesses. It seeks to capture the price changes in all the products sold by U.S. businesses to anyone anywhere, including foreigners buying exports, government purchases, and capital investment.

The PPI allows us to break down the headline number into components. Looking at the one-year changes through April 2022, we discover that the prices of government purchased goods–minus food and energy–rose 10.4 percent. Prices of exported goods–minus food and energy–rose 12.5 percent, while prices of sales to the domestic private sector—consumers and businesses—were up 8.6 percent. The overall number was 10 percent. This tells us that big government payments are still playing a role in pushing inflation up, as is rising demand for U.S. exports from the recovering economies of Europe and elsewhere.

The monthly private sector figure for prices of core goods—minus food and energy—shows no slowdown in inflation at all. Prices rose 0.9 percent in April just as they did in March. The annual figure of 8.6 is an acceleration from 8.1 percent in the prior month. If we break that down even further, however, we see that core consumer goods prices accelerated from a 0.7 percent monthly gain in March to 0.8 percent in April. The year-over-year figure jumped from 7.7 percent in March to eight percent in April.

Of course, food and energy are important—perhaps the most important—parts of inflation for many households. If we add those back in, the private sector is facing 15.6 percent annual inflation. This is up from 15.3 percent in March and has been rising every month this year. This is why even if the headlines say inflation is decelerating, the American public are likely to sense that prices are still rising far too rapidly.

To view online: https://www.breitbart.com/economy/2022/05/12/breitbart-business-digest-bad-news-and-worse-news-on-inflation/