| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Harris County, Texas shows the possibilities of bail reform. |

| Date | March 29, 2022 2:07 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Fewer misdemeanor convictions, shorter jail stays, and no increase in pretrial arrests for new offenses.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for March 29, 2022 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

What does successful bail reform look like? To start, look to Harris County, Texas. [[link removed]] New data supports what advocates have been saying all along: there’s no need to detain so many people pretrial. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

New data [[link removed]] is out that supports bail reform efforts to end reliance on cash bail, minimize the number of people charged with misdemeanors and detained pretrial, and improve misdemeanor bail hearings. The recently published findings come from researchers charged with monitoring misdemeanor pretrial reform as it is implemented in Harris County (Houston), Texas.

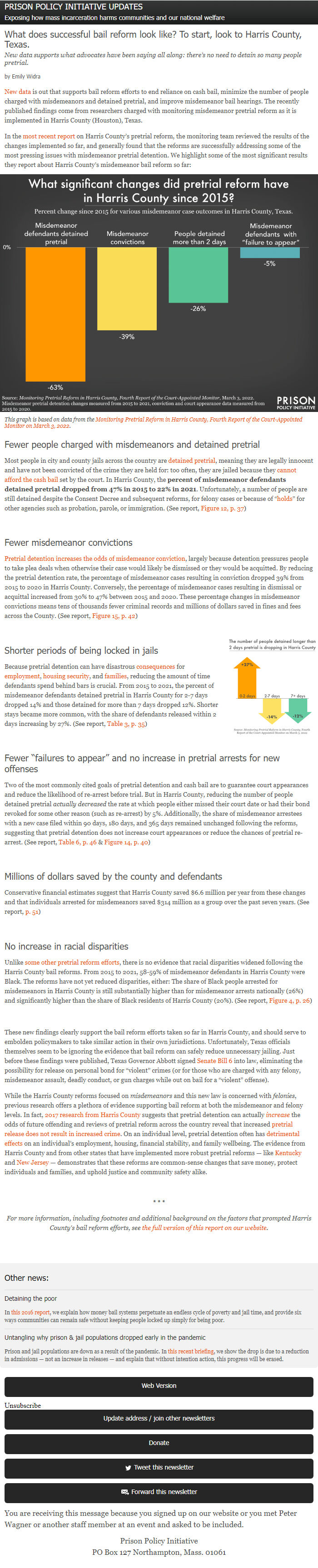

In the most recent report [[link removed]] on Harris County’s pretrial reform, the monitoring team reviewed the results of the changes implemented so far, and generally found that the reforms are successfully addressing some of the most pressing issues with misdemeanor pretrial detention. We highlight some of the most significant results they report about Harris County’s misdemeanor bail reform so far:

This graph is based on data from the Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Fourth Report of the Court-Appointed Monitor on March 3, 2022 [[link removed]].

Fewer people charged with misdemeanors and detained pretrial

Most people in city and county jails across the country are detained pretrial [[link removed]], meaning they are legally innocent and have not been convicted of the crime they are held for: too often, they are jailed because they cannot afford the cash bail [[link removed]] set by the court. In Harris County, the percent of misdemeanor defendants detained pretrial dropped from 47% in 2015 to 22% in 2021. Unfortunately, a number of people are still detained despite the Consent Decree and subsequent reforms, for felony cases or because of “ holds [[link removed]]” for other agencies such as probation, parole, or immigration. (See report, Figure 12, p. 37 [[link removed]])

Fewer misdemeanor convictions

Pretrial detention increases the odds of misdemeanor conviction [[link removed]], largely because detention pressures people to take plea deals when otherwise their case would likely be dismissed or they would be acquitted. By reducing the pretrial detention rate, the percentage of misdemeanor cases resulting in conviction dropped 39% from 2015 to 2020 in Harris County. Conversely, the percentage of misdemeanor cases resulting in dismissal or acquittal increased from 30% to 47% between 2015 and 2020. These percentage changes in misdemeanor convictions means tens of thousands fewer criminal records and millions of dollars saved in fines and fees across the County. (See report, Figure 15, p. 42 [[link removed]])

Shorter periods of being locked in jails

Because pretrial detention can have disastrous consequences [[link removed]] for employment [[link removed]], housing security [[link removed]], and families [[link removed]], reducing the amount of time defendants spend behind bars is crucial. From 2015 to 2021, the percent of misdemeanor defendants detained pretrial in Harris County for 2-7 days dropped 14% and those detained for more than 7 days dropped 12%. Shorter stays became more common, with the share of defendants released within 2 days increasing by 27%. (See report, Table 3, p. 35 [[link removed]])

Fewer “failures to appear” and no increase in pretrial arrests for new offenses

Two of the most commonly cited goals of pretrial detention and cash bail are to guarantee court appearances and reduce the likelihood of re-arrest before trial. But in Harris County, reducing the number of people detained pretrial actually decreased the rate at which people either missed their court date or had their bond revoked for some other reason (such as re-arrest) by 5%. Additionally, the share of misdemeanor arrestees with a new case filed within 90 days, 180 days, and 365 days remained unchanged following the reforms, suggesting that pretrial detention does not increase court appearances or reduce the chances of pretrial re-arrest. (See report, Table 6, p. 46 [[link removed]] & Figure 14, p. 40 [[link removed]])

Millions of dollars saved by the county and defendants

Conservative financial estimates suggest that Harris County saved $6.6 million per year from these changes and that individuals arrested for misdemeanors saved $314 million as a group over the past seven years. (See report, p. 51 [[link removed]])

No increase in racial disparities

Unlike [[link removed]] some other pretrial [[link removed]] reform efforts [[link removed]], there is no evidence that racial disparities widened following the Harris County bail reforms. From 2015 to 2021, 58-59% of misdemeanor defendants in Harris County were Black. The reforms have not yet reduced disparities, either: The share of Black people arrested for misdemeanors in Harris County is still substantially higher than for misdemeanor arrests nationally (26%) and significantly higher than the share of Black residents of Harris County (20%). (See report, Figure 4, p. 26 [[link removed]])

These new findings clearly support the bail reform efforts taken so far in Harris County, and should serve to embolden policymakers to take similar action in their own jurisdictions. Unfortunately, Texas officials themselves seem to be ignoring the evidence that bail reform can safely reduce unnecessary jailing. Just before these findings were published, Texas Governor Abbott signed Senate Bill 6 [[link removed]] into law, eliminating the possibility for release on personal bond for “violent” crimes (or for those who are charged with any felony, misdemeanor assault, deadly conduct, or gun charges while out on bail for a “violent” offense).

While the Harris County reforms focused on misdemeanors and this new law is concerned with felonies, previous research offers a plethora of evidence supporting bail reform at both the misdemeanor and felony levels. In fact, 2017 research from Harris County [[link removed]] suggests that pretrial detention can actually increase [[link removed]] the odds of future offending and reviews of pretrial reform across the country reveal that increased pretrial release does not result in increased crime [[link removed]]. On an individual level, pretrial detention often has detrimental effects [[link removed]] on an individual’s employment, housing, financial stability, and family wellbeing. The evidence from Harris County and from other states that have implemented more robust pretrial reforms — like Kentucky [[link removed]] and New Jersey [[link removed]] — demonstrates that these reforms are common-sense changes that save money, protect individuals and families, and uphold justice and community safety alike.

* * *

For more information, including footnotes and additional background on the factors that prompted Harris County's bail reform efforts, see the full version of this report on our website [[link removed]].

Help us lift up the truth [[link removed]]

Too often, policymakers roll back or stall bail reform efforts using fear-mongering and false narratives about crime. We lift up the facts in briefings like this one, to show that ending cash bail and releasing people pre-trial isn’t dangerous. Can you support this work with a donation today? [[link removed]] Thank you!

Other news: Detaining the poor [[link removed]]

In this 2016 report [[link removed]], we explain how money bail systems perpetuate an endless cycle of poverty and jail time, and provide six ways communities can remain safe without keeping people locked up simply for being poor.

Untangling why prison & jail populations dropped early in the pandemic [[link removed]]

Prison and jail populations are down as a result of the pandemic. In this recent briefing [[link removed]], we show the drop is due to a reduction in admissions — not an increase in releases — and explain that without intention action, this progress will be erased.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for March 29, 2022 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

What does successful bail reform look like? To start, look to Harris County, Texas. [[link removed]] New data supports what advocates have been saying all along: there’s no need to detain so many people pretrial. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

New data [[link removed]] is out that supports bail reform efforts to end reliance on cash bail, minimize the number of people charged with misdemeanors and detained pretrial, and improve misdemeanor bail hearings. The recently published findings come from researchers charged with monitoring misdemeanor pretrial reform as it is implemented in Harris County (Houston), Texas.

In the most recent report [[link removed]] on Harris County’s pretrial reform, the monitoring team reviewed the results of the changes implemented so far, and generally found that the reforms are successfully addressing some of the most pressing issues with misdemeanor pretrial detention. We highlight some of the most significant results they report about Harris County’s misdemeanor bail reform so far:

This graph is based on data from the Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Fourth Report of the Court-Appointed Monitor on March 3, 2022 [[link removed]].

Fewer people charged with misdemeanors and detained pretrial

Most people in city and county jails across the country are detained pretrial [[link removed]], meaning they are legally innocent and have not been convicted of the crime they are held for: too often, they are jailed because they cannot afford the cash bail [[link removed]] set by the court. In Harris County, the percent of misdemeanor defendants detained pretrial dropped from 47% in 2015 to 22% in 2021. Unfortunately, a number of people are still detained despite the Consent Decree and subsequent reforms, for felony cases or because of “ holds [[link removed]]” for other agencies such as probation, parole, or immigration. (See report, Figure 12, p. 37 [[link removed]])

Fewer misdemeanor convictions

Pretrial detention increases the odds of misdemeanor conviction [[link removed]], largely because detention pressures people to take plea deals when otherwise their case would likely be dismissed or they would be acquitted. By reducing the pretrial detention rate, the percentage of misdemeanor cases resulting in conviction dropped 39% from 2015 to 2020 in Harris County. Conversely, the percentage of misdemeanor cases resulting in dismissal or acquittal increased from 30% to 47% between 2015 and 2020. These percentage changes in misdemeanor convictions means tens of thousands fewer criminal records and millions of dollars saved in fines and fees across the County. (See report, Figure 15, p. 42 [[link removed]])

Shorter periods of being locked in jails

Because pretrial detention can have disastrous consequences [[link removed]] for employment [[link removed]], housing security [[link removed]], and families [[link removed]], reducing the amount of time defendants spend behind bars is crucial. From 2015 to 2021, the percent of misdemeanor defendants detained pretrial in Harris County for 2-7 days dropped 14% and those detained for more than 7 days dropped 12%. Shorter stays became more common, with the share of defendants released within 2 days increasing by 27%. (See report, Table 3, p. 35 [[link removed]])

Fewer “failures to appear” and no increase in pretrial arrests for new offenses

Two of the most commonly cited goals of pretrial detention and cash bail are to guarantee court appearances and reduce the likelihood of re-arrest before trial. But in Harris County, reducing the number of people detained pretrial actually decreased the rate at which people either missed their court date or had their bond revoked for some other reason (such as re-arrest) by 5%. Additionally, the share of misdemeanor arrestees with a new case filed within 90 days, 180 days, and 365 days remained unchanged following the reforms, suggesting that pretrial detention does not increase court appearances or reduce the chances of pretrial re-arrest. (See report, Table 6, p. 46 [[link removed]] & Figure 14, p. 40 [[link removed]])

Millions of dollars saved by the county and defendants

Conservative financial estimates suggest that Harris County saved $6.6 million per year from these changes and that individuals arrested for misdemeanors saved $314 million as a group over the past seven years. (See report, p. 51 [[link removed]])

No increase in racial disparities

Unlike [[link removed]] some other pretrial [[link removed]] reform efforts [[link removed]], there is no evidence that racial disparities widened following the Harris County bail reforms. From 2015 to 2021, 58-59% of misdemeanor defendants in Harris County were Black. The reforms have not yet reduced disparities, either: The share of Black people arrested for misdemeanors in Harris County is still substantially higher than for misdemeanor arrests nationally (26%) and significantly higher than the share of Black residents of Harris County (20%). (See report, Figure 4, p. 26 [[link removed]])

These new findings clearly support the bail reform efforts taken so far in Harris County, and should serve to embolden policymakers to take similar action in their own jurisdictions. Unfortunately, Texas officials themselves seem to be ignoring the evidence that bail reform can safely reduce unnecessary jailing. Just before these findings were published, Texas Governor Abbott signed Senate Bill 6 [[link removed]] into law, eliminating the possibility for release on personal bond for “violent” crimes (or for those who are charged with any felony, misdemeanor assault, deadly conduct, or gun charges while out on bail for a “violent” offense).

While the Harris County reforms focused on misdemeanors and this new law is concerned with felonies, previous research offers a plethora of evidence supporting bail reform at both the misdemeanor and felony levels. In fact, 2017 research from Harris County [[link removed]] suggests that pretrial detention can actually increase [[link removed]] the odds of future offending and reviews of pretrial reform across the country reveal that increased pretrial release does not result in increased crime [[link removed]]. On an individual level, pretrial detention often has detrimental effects [[link removed]] on an individual’s employment, housing, financial stability, and family wellbeing. The evidence from Harris County and from other states that have implemented more robust pretrial reforms — like Kentucky [[link removed]] and New Jersey [[link removed]] — demonstrates that these reforms are common-sense changes that save money, protect individuals and families, and uphold justice and community safety alike.

* * *

For more information, including footnotes and additional background on the factors that prompted Harris County's bail reform efforts, see the full version of this report on our website [[link removed]].

Help us lift up the truth [[link removed]]

Too often, policymakers roll back or stall bail reform efforts using fear-mongering and false narratives about crime. We lift up the facts in briefings like this one, to show that ending cash bail and releasing people pre-trial isn’t dangerous. Can you support this work with a donation today? [[link removed]] Thank you!

Other news: Detaining the poor [[link removed]]

In this 2016 report [[link removed]], we explain how money bail systems perpetuate an endless cycle of poverty and jail time, and provide six ways communities can remain safe without keeping people locked up simply for being poor.

Untangling why prison & jail populations dropped early in the pandemic [[link removed]]

Prison and jail populations are down as a result of the pandemic. In this recent briefing [[link removed]], we show the drop is due to a reduction in admissions — not an increase in releases — and explain that without intention action, this progress will be erased.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor