| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | What is "the law," anyways? |

| Date | March 21, 2022 3:33 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

The legitimacy of legal systems across the world is coming into deep question. In Russia, it has become a crime punishable by 15 years in prison to call the invasion of Ukraine an invasion [[link removed]]. In China, even billionaires disappear when they grumble about the misuse of government power [[link removed]]. And in the United States, laws across the nation have criminalized the mere act of taking a photograph of animal cruelty [[link removed]]. The law, it seems, is too often just a pretext for the powerful to do what they want. Yet while we are quick to attack particular nations or politicians, for abusing our legal system, few have questioned the deeper political assumptions at the heart of our crumbling sense of order. And as I recently discussed in a conversation with my friend Sailesh Rao, founder of Climate Healers, these flawed assumptions are a fundamental stumbling block towards creating a system of “order” that actually works.

Check out the conversation I had with Sailesh Rao on the false political assumptions that are blocking progress on issues ranging from income inequality to climate justice [[link removed]].

Take popular conceptions of “the law.”

There are two false beliefs, commonly held even by lawyers, that most people have about the law. First, most take for granted that “the law” is something that’s fixed, objective, and certain. Thus the phrase “rule by law, and not men.” The law, it is said, is something different from one man’s opinion or ideology. It’s a fact. Think of the metaphor of law as a physical manuscript, perhaps a scroll. The benefit of this concreteness is that we can clearly understand what the law is. “Just look here,” we can say, pointing to the scroll. “That is the law.” Scholars call this “legal positivism” but let’s call it something more straightforward: legal certainty.

The first false belief leads to the second one: that, in a well functioning society, the law should always be obeyed. If the law is clear and real, then no one has any excuse to break it. After all, the rules have been set out, and they are so obvious and clear! Anyone who breaks them must be a bad person or, worse yet, a psychopath who simply does not care for what others feel and think. Let’s call this belief “legal obedience.”

One of the strange things about these two beliefs — legal certainty and legal obedience — is that many who actually study the question (“What is the law, anyways?”) don’t agree with either of them. This is especially true when it comes to a society’s most important and basic legal principles: freedom of speech; equal protection; or due process. These principles are widely understood to be evolving, not fixed, and to be strengthened (and not weakened) by disobedience and dissent. Indeed, this is why one of our founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, believed that the US Constitution should be rewritten every 20 years [[link removed]].

What’s wrong with a fixed and obedient conception of law? Let’s take each of the beliefs in turn.

The law shouldn’t be fixed for the exact reason that we as individual human beings are not fixed. There have been 27 amendments to the US Constitution, including 10 that were passed at this nation’s founding. And, as I say in the conversation with Sailesh, any human being who makes only 20 changes, over the course of 200 years, would be rightly seen as a stubborn narcissist. Life and growth are all about change! And the only way for a constitution to survive 200+ years of a nation’s development, with only 27 formal amendments, is for it to be subject to other informal amendments: i.e., evolving interpretations pursuant to a fluid, rather than fixed, understanding. That’s exactly what we’ve done over our nation’s history, from Brown v. Board of Education [[link removed]] to Obergefell v. Hodges [[link removed]]. Brown evolved our conception of racial equality, in a way the drafters of the Constitution would never have understood. Obergefell evolved our conception of equity in a domain, sexual orientation, that wasn’t even a political issue when the Constitution was drafted. And yet those cases, and not a decaying piece of parchment, are the law. They show that a proper conception of law is not fixed; it evolves.

And that brings us to the second false belief: that the law must be obeyed. This false notion was perpetuated by legal philosopher John Austin, who believed that law was just a command backed up by force, subject to habitual obedience. This primitive conception once dominated thinking on legal philosophy, which sought to turn law into something like a science. What the law is, philosophers argued, is different from what the law should be. Obedience, therefore, became part of the definition of “the law.”

What this definition misses, however, is that, if the law is evolving rather than fixed, there will be times that evolving legal principles require disobedience rather than compliance. And that disobedience is exactly what’s required for a functioning legal system. Take racial justice. The mass law breaking activity that occurred in the 1960s was highly disobedient. People openly traveled on white sections of the bus; they sat in white seats at the local diner; and they demanded access to white schools. All of this was breaking the rules, as written on various pieces of paper, and as pronounced by various judges (then, as now, mostly powerful men wearing strange black robes). And, yet, within years of this mass disobedience, the very things that were once considered illegal (e.g., sitting in the white section of a public bus) were transformed into constitutional rights. Any coherent theory of “the law” has to grapple with this. And anyone who’s interested in how to change the law, and the society that it governs, must understand how “the law” can make such sudden 180 degree turns — and still maintain legitimacy before the people.

I explain my own theory on how this happens in the conversation with Sailesh. In a nutshell, legal evolution and disobedience that pass what I’ve previously called “the moral stress test” — i.e., does it benefit the least powerful, and not the most powerful? — can properly be understood as part of “the law,” even if it’s not yet written on a piece of paper. When we understand the concept of law through this lens, it makes clear why, for example, Russia’s efforts to ban the word “invasion” are unlawful (even if they are written on the right pieces of paper). And why many of the brave activists, such as Marina Ovsyannikova, who disrupted state TV with an anti-war protest, are acting lawfully (even if they are charged with crimes for violating the rules written on those same pieces of paper). The Russian government’s efforts were intended to protect its own power structure from critique. Marina’s actions, in contrast, were meant to give voice to a community that was suffering from violence that contradicts the most basic values of Russian (and human) society.

I’ll be the first to say that the moral stress test theory is highly underdeveloped. And I am not saying there are no hard cases, e.g., how does one decide what evolutions benefit the powerless? And who gets to make this determination? But the existence of tough questions is not a reason to discard a theory, if it’s better than the alternatives. And the moral stress test is still, in my view, the best description and justification for “the law.” It also goes a long way toward explaining my belief in direct action for animal rights [[link removed]], and my belief in the centrality of the animal rights movement in achieving a better world for all beings. As I argued at Yale back in early 2020, the animals will always be the most powerless beings in our society. If the law serves them, it serves us all.

But the key thing is that it’s not enough for these conversations to happen in blogs and philosophy seminars. To solve the crisis of authority, we need a more sophisticated conception of law that is widely embraced and understood. That’s why I was so happy to have this conversation with Sailesh. Because I want to make the case that, sometimes, breaking the rules is not just the right, but the lawful thing to do.

Give the conversation a listen, and let me know what you think! [[link removed]]

Unsubscribe [link removed]

The legitimacy of legal systems across the world is coming into deep question. In Russia, it has become a crime punishable by 15 years in prison to call the invasion of Ukraine an invasion [[link removed]]. In China, even billionaires disappear when they grumble about the misuse of government power [[link removed]]. And in the United States, laws across the nation have criminalized the mere act of taking a photograph of animal cruelty [[link removed]]. The law, it seems, is too often just a pretext for the powerful to do what they want. Yet while we are quick to attack particular nations or politicians, for abusing our legal system, few have questioned the deeper political assumptions at the heart of our crumbling sense of order. And as I recently discussed in a conversation with my friend Sailesh Rao, founder of Climate Healers, these flawed assumptions are a fundamental stumbling block towards creating a system of “order” that actually works.

Check out the conversation I had with Sailesh Rao on the false political assumptions that are blocking progress on issues ranging from income inequality to climate justice [[link removed]].

Take popular conceptions of “the law.”

There are two false beliefs, commonly held even by lawyers, that most people have about the law. First, most take for granted that “the law” is something that’s fixed, objective, and certain. Thus the phrase “rule by law, and not men.” The law, it is said, is something different from one man’s opinion or ideology. It’s a fact. Think of the metaphor of law as a physical manuscript, perhaps a scroll. The benefit of this concreteness is that we can clearly understand what the law is. “Just look here,” we can say, pointing to the scroll. “That is the law.” Scholars call this “legal positivism” but let’s call it something more straightforward: legal certainty.

The first false belief leads to the second one: that, in a well functioning society, the law should always be obeyed. If the law is clear and real, then no one has any excuse to break it. After all, the rules have been set out, and they are so obvious and clear! Anyone who breaks them must be a bad person or, worse yet, a psychopath who simply does not care for what others feel and think. Let’s call this belief “legal obedience.”

One of the strange things about these two beliefs — legal certainty and legal obedience — is that many who actually study the question (“What is the law, anyways?”) don’t agree with either of them. This is especially true when it comes to a society’s most important and basic legal principles: freedom of speech; equal protection; or due process. These principles are widely understood to be evolving, not fixed, and to be strengthened (and not weakened) by disobedience and dissent. Indeed, this is why one of our founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, believed that the US Constitution should be rewritten every 20 years [[link removed]].

What’s wrong with a fixed and obedient conception of law? Let’s take each of the beliefs in turn.

The law shouldn’t be fixed for the exact reason that we as individual human beings are not fixed. There have been 27 amendments to the US Constitution, including 10 that were passed at this nation’s founding. And, as I say in the conversation with Sailesh, any human being who makes only 20 changes, over the course of 200 years, would be rightly seen as a stubborn narcissist. Life and growth are all about change! And the only way for a constitution to survive 200+ years of a nation’s development, with only 27 formal amendments, is for it to be subject to other informal amendments: i.e., evolving interpretations pursuant to a fluid, rather than fixed, understanding. That’s exactly what we’ve done over our nation’s history, from Brown v. Board of Education [[link removed]] to Obergefell v. Hodges [[link removed]]. Brown evolved our conception of racial equality, in a way the drafters of the Constitution would never have understood. Obergefell evolved our conception of equity in a domain, sexual orientation, that wasn’t even a political issue when the Constitution was drafted. And yet those cases, and not a decaying piece of parchment, are the law. They show that a proper conception of law is not fixed; it evolves.

And that brings us to the second false belief: that the law must be obeyed. This false notion was perpetuated by legal philosopher John Austin, who believed that law was just a command backed up by force, subject to habitual obedience. This primitive conception once dominated thinking on legal philosophy, which sought to turn law into something like a science. What the law is, philosophers argued, is different from what the law should be. Obedience, therefore, became part of the definition of “the law.”

What this definition misses, however, is that, if the law is evolving rather than fixed, there will be times that evolving legal principles require disobedience rather than compliance. And that disobedience is exactly what’s required for a functioning legal system. Take racial justice. The mass law breaking activity that occurred in the 1960s was highly disobedient. People openly traveled on white sections of the bus; they sat in white seats at the local diner; and they demanded access to white schools. All of this was breaking the rules, as written on various pieces of paper, and as pronounced by various judges (then, as now, mostly powerful men wearing strange black robes). And, yet, within years of this mass disobedience, the very things that were once considered illegal (e.g., sitting in the white section of a public bus) were transformed into constitutional rights. Any coherent theory of “the law” has to grapple with this. And anyone who’s interested in how to change the law, and the society that it governs, must understand how “the law” can make such sudden 180 degree turns — and still maintain legitimacy before the people.

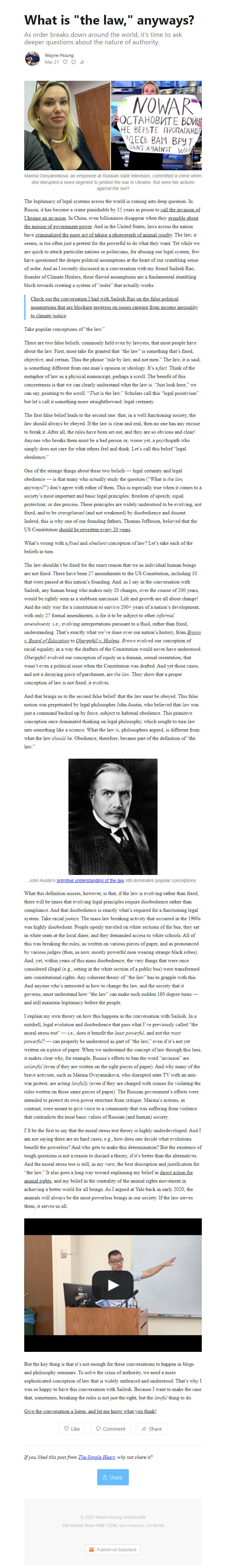

I explain my own theory on how this happens in the conversation with Sailesh. In a nutshell, legal evolution and disobedience that pass what I’ve previously called “the moral stress test” — i.e., does it benefit the least powerful, and not the most powerful? — can properly be understood as part of “the law,” even if it’s not yet written on a piece of paper. When we understand the concept of law through this lens, it makes clear why, for example, Russia’s efforts to ban the word “invasion” are unlawful (even if they are written on the right pieces of paper). And why many of the brave activists, such as Marina Ovsyannikova, who disrupted state TV with an anti-war protest, are acting lawfully (even if they are charged with crimes for violating the rules written on those same pieces of paper). The Russian government’s efforts were intended to protect its own power structure from critique. Marina’s actions, in contrast, were meant to give voice to a community that was suffering from violence that contradicts the most basic values of Russian (and human) society.

I’ll be the first to say that the moral stress test theory is highly underdeveloped. And I am not saying there are no hard cases, e.g., how does one decide what evolutions benefit the powerless? And who gets to make this determination? But the existence of tough questions is not a reason to discard a theory, if it’s better than the alternatives. And the moral stress test is still, in my view, the best description and justification for “the law.” It also goes a long way toward explaining my belief in direct action for animal rights [[link removed]], and my belief in the centrality of the animal rights movement in achieving a better world for all beings. As I argued at Yale back in early 2020, the animals will always be the most powerless beings in our society. If the law serves them, it serves us all.

But the key thing is that it’s not enough for these conversations to happen in blogs and philosophy seminars. To solve the crisis of authority, we need a more sophisticated conception of law that is widely embraced and understood. That’s why I was so happy to have this conversation with Sailesh. Because I want to make the case that, sometimes, breaking the rules is not just the right, but the lawful thing to do.

Give the conversation a listen, and let me know what you think! [[link removed]]

Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Substack