| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | 1.6 Billion Reasons Why Activists Say New York City Needs Public Banking |

| Date | December 4, 2021 7:15 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[“A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison]

[[link removed]]

1.6 BILLION REASONS WHY ACTIVISTS SAY NEW YORK CITY NEEDS PUBLIC

BANKING

[[link removed]]

Glenn Daigon

November 24, 2021

WhoWhatWhy

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ “A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison _

Bank, by 401(K) 2013 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New York City, once the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the

United States, is bouncing back. Broadway

[[link removed]] is

reopening its doors, international tourists are arriving, and workers

are returning to jobs

[[link removed]].

But not all the way. According to the New York City Recovery Index

[[link removed]],

the city is still just about 80 percent “back.” Hotels are still

running deficits

[[link removed]],

office vacancies

[[link removed]] are

at a 30-year high, and small businesses — hundreds

[[link removed]] of

which closed in 2020 and 2021 — are facing long roads to recovery.

What’s slowing Gotham down? According to critics, the pandemic laid

bare the city’s systemic inequalities. COVID-19 infection and death

rates were highest in working-class, non-white neighborhoods. Not only

did private, for-profit banking aggravate those inequalities, but

during the pandemic, JP Morgan Chase also extracted $1 billion in

overdraft fees

[[link removed]] from

working-class New Yorkers, according to research from the New Economy

Project, a nonprofit organizing around issues of equity and racial

justice.

“As New Yorkers struggled, banks smuggled massive sums in predatory

fees out of hard hit communities of color,” said Andy Morrison

[[link removed]],

an associate director at the organization.

“A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison

Meanwhile, those same commercial banks — which by city law must

handle the nearly $100 billion in public funds that flow through New

York’s public coffers in the form of sales and property taxes,

revenue bonds, and federal stimulus cash — pay only “modest”

interest rates for holding all that public money, Morrison argued in

an analysis

[[link removed]] published

by the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

Unequal access to resources like capital has long been a problem for

working-class and minority communities. White households average

nearly eight times the net worth of Black households, and banking

practices are one reason why, a Brookings Institution analysis found

[[link removed]].

According to critics like Morrison, this hard reality and New York’s

slow recovery all create momentum for New York City to finally set up

an alternative to private banks.

Savage Inequalities

JPMorgan Chase, with which New York City does most of its banking, is

the worst offender but not alone. Banks have charged New York

customers more than $1.6 billion in fees

[[link removed]] since

the pandemic began, mainly through overdraft fees but also in ATM fees

and monthly “maintenance” fees, as Public Bank NYC

[[link removed]], a coalition dedicated to

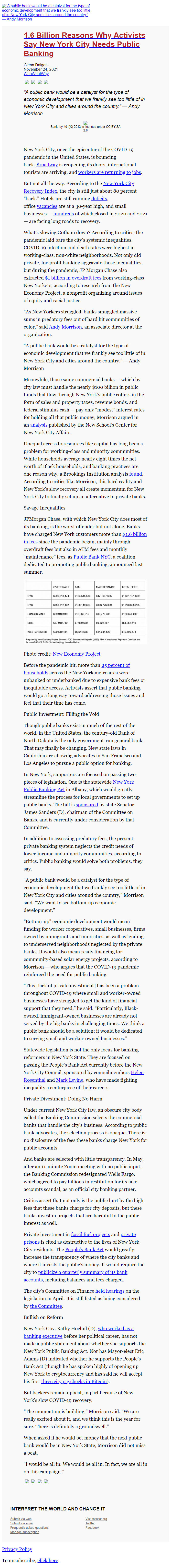

promoting public banking, announced last summer.

[New York, bank fees, chart]

[[link removed]]

Photo credit: New Economy Project

[[link removed]]

Before the pandemic hit, more than 25 percent of households

[[link removed]] across

the New York metro area were unbanked or underbanked due to expensive

bank fees or inequitable access. Activists assert that public banking

would go a long way toward addressing those issues and feel that their

time has come.

Public Investment: Filling the Void

Though public banks exist in much of the rest of the world, in the

United States, the century-old Bank of North Dakota is the only

government-run general bank. That may finally be changing. New state

laws in California are allowing advocates in San Francisco and Los

Angeles to pursue a public option for banking.

In New York, supporters are focused on passing two pieces of

legislation. One is the statewide New York Public Banking Act

[[link removed]] in

Albany, which would greatly streamline the process for local

governments to set up public banks. The bill is sponsored

[[link removed]] by state

Senator James Sanders (D), chairman of the Committee on Banks, and is

currently under consideration by that Committee.

In addition to assessing predatory fees, the present private banking

system neglects the credit needs of lower-income and minority

communities, according to critics. Public banking would solve both

problems, they say.

“A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country,” Morrison said. “We want to see

bottom-up economic development.”

“Bottom-up” economic development would mean funding for worker

cooperatives, small businesses, firms owned by immigrants and

minorities, as well as lending to underserved neighborhoods neglected

by the private banks. It would also mean ready financing for

community-based solar energy projects, according to Morrison — who

argues that the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the need for public

banking.

“This [lack of private investment] has been a problem throughout

COVID-19 where small and worker-owned businesses have struggled to get

the kind of financial support that they need,” he said.

“Particularly, Black-owned, immigrant-owned businesses are already

not served by the big banks in challenging times. We think a public

bank should be a solution; it would be dedicated to serving small and

worker-owned businesses.”

Statewide legislation is not the only focus for banking reformers in

New York State. They are focused on passing the People’s Bank Act

currently before the New York City Council, sponsored by

councilmembers Helen Rosenthal

[[link removed]] and Mark Levine

[[link removed]], who have made fighting

inequality a centerpiece of their careers.

Private Divestment: Doing No Harm

Under current New York City law, an obscure city body called the

Banking Commission selects the commercial banks that handle the

city’s business. According to public bank advocates, the selection

process is opaque. There is no disclosure of the fees these banks

charge New York for public accounts.

And banks are selected with little transparency. In May, after an

11-minute Zoom meeting with no public input, the Banking Commission

redesignated Wells Fargo, which agreed to pay billions in restitution

for its fake accounts scandal, as an official city banking partner.

Critics assert that not only is the public hurt by the high fees that

these banks charge for city deposits, but these banks invest in

projects that are harmful to the public interest as well.

Private investment in fossil fuel projects

[[link removed]] and private

prisons

[[link removed]] is

cited as destructive to the lives of New York City residents.

The People’s Bank Act

[[link removed]] would

greatly increase the transparency of where the city banks and where it

invests the public’s money. It would require the city to publicize

a quarterly summary of its bank accounts

[[link removed]],

including balances and fees charged.

The city’s Committee on Finance held hearings

[[link removed]] on

the legislation in April. It is still listed as being considered

by the Committee

[[link removed]].

Bullish on Reform

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D), who worked as a banking executive

[[link removed]] before

her political career, has not made a public statement about whether

she supports the New York Public Banking Act. Nor has Mayor-elect Eric

Adams (D) indicated whether he supports the People’s Bank Act

(though he has spoken highly of opening up New York to cryptocurrency

and has said he will accept his first three city paychecks in Bitcoin

[[link removed]]).

But backers remain upbeat, in part because of New York’s slow

COVID-19 recovery.

“The momentum is building,” Morrison said. “We are really

excited about it, and we think this is the year for sure. There is

definitely a groundswell.”

When asked if he would bet money that the next public bank would be in

New York State, Morrison did not miss a beat.

“I would be all in. We would be all in. In fact, we are all in on

this campaign.”

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison]

[[link removed]]

1.6 BILLION REASONS WHY ACTIVISTS SAY NEW YORK CITY NEEDS PUBLIC

BANKING

[[link removed]]

Glenn Daigon

November 24, 2021

WhoWhatWhy

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ “A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison _

Bank, by 401(K) 2013 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New York City, once the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the

United States, is bouncing back. Broadway

[[link removed]] is

reopening its doors, international tourists are arriving, and workers

are returning to jobs

[[link removed]].

But not all the way. According to the New York City Recovery Index

[[link removed]],

the city is still just about 80 percent “back.” Hotels are still

running deficits

[[link removed]],

office vacancies

[[link removed]] are

at a 30-year high, and small businesses — hundreds

[[link removed]] of

which closed in 2020 and 2021 — are facing long roads to recovery.

What’s slowing Gotham down? According to critics, the pandemic laid

bare the city’s systemic inequalities. COVID-19 infection and death

rates were highest in working-class, non-white neighborhoods. Not only

did private, for-profit banking aggravate those inequalities, but

during the pandemic, JP Morgan Chase also extracted $1 billion in

overdraft fees

[[link removed]] from

working-class New Yorkers, according to research from the New Economy

Project, a nonprofit organizing around issues of equity and racial

justice.

“As New Yorkers struggled, banks smuggled massive sums in predatory

fees out of hard hit communities of color,” said Andy Morrison

[[link removed]],

an associate director at the organization.

“A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country.” — Andy Morrison

Meanwhile, those same commercial banks — which by city law must

handle the nearly $100 billion in public funds that flow through New

York’s public coffers in the form of sales and property taxes,

revenue bonds, and federal stimulus cash — pay only “modest”

interest rates for holding all that public money, Morrison argued in

an analysis

[[link removed]] published

by the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

Unequal access to resources like capital has long been a problem for

working-class and minority communities. White households average

nearly eight times the net worth of Black households, and banking

practices are one reason why, a Brookings Institution analysis found

[[link removed]].

According to critics like Morrison, this hard reality and New York’s

slow recovery all create momentum for New York City to finally set up

an alternative to private banks.

Savage Inequalities

JPMorgan Chase, with which New York City does most of its banking, is

the worst offender but not alone. Banks have charged New York

customers more than $1.6 billion in fees

[[link removed]] since

the pandemic began, mainly through overdraft fees but also in ATM fees

and monthly “maintenance” fees, as Public Bank NYC

[[link removed]], a coalition dedicated to

promoting public banking, announced last summer.

[New York, bank fees, chart]

[[link removed]]

Photo credit: New Economy Project

[[link removed]]

Before the pandemic hit, more than 25 percent of households

[[link removed]] across

the New York metro area were unbanked or underbanked due to expensive

bank fees or inequitable access. Activists assert that public banking

would go a long way toward addressing those issues and feel that their

time has come.

Public Investment: Filling the Void

Though public banks exist in much of the rest of the world, in the

United States, the century-old Bank of North Dakota is the only

government-run general bank. That may finally be changing. New state

laws in California are allowing advocates in San Francisco and Los

Angeles to pursue a public option for banking.

In New York, supporters are focused on passing two pieces of

legislation. One is the statewide New York Public Banking Act

[[link removed]] in

Albany, which would greatly streamline the process for local

governments to set up public banks. The bill is sponsored

[[link removed]] by state

Senator James Sanders (D), chairman of the Committee on Banks, and is

currently under consideration by that Committee.

In addition to assessing predatory fees, the present private banking

system neglects the credit needs of lower-income and minority

communities, according to critics. Public banking would solve both

problems, they say.

“A public bank would be a catalyst for the type of economic

development that we frankly see too little of in New York City and

cities around the country,” Morrison said. “We want to see

bottom-up economic development.”

“Bottom-up” economic development would mean funding for worker

cooperatives, small businesses, firms owned by immigrants and

minorities, as well as lending to underserved neighborhoods neglected

by the private banks. It would also mean ready financing for

community-based solar energy projects, according to Morrison — who

argues that the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the need for public

banking.

“This [lack of private investment] has been a problem throughout

COVID-19 where small and worker-owned businesses have struggled to get

the kind of financial support that they need,” he said.

“Particularly, Black-owned, immigrant-owned businesses are already

not served by the big banks in challenging times. We think a public

bank should be a solution; it would be dedicated to serving small and

worker-owned businesses.”

Statewide legislation is not the only focus for banking reformers in

New York State. They are focused on passing the People’s Bank Act

currently before the New York City Council, sponsored by

councilmembers Helen Rosenthal

[[link removed]] and Mark Levine

[[link removed]], who have made fighting

inequality a centerpiece of their careers.

Private Divestment: Doing No Harm

Under current New York City law, an obscure city body called the

Banking Commission selects the commercial banks that handle the

city’s business. According to public bank advocates, the selection

process is opaque. There is no disclosure of the fees these banks

charge New York for public accounts.

And banks are selected with little transparency. In May, after an

11-minute Zoom meeting with no public input, the Banking Commission

redesignated Wells Fargo, which agreed to pay billions in restitution

for its fake accounts scandal, as an official city banking partner.

Critics assert that not only is the public hurt by the high fees that

these banks charge for city deposits, but these banks invest in

projects that are harmful to the public interest as well.

Private investment in fossil fuel projects

[[link removed]] and private

prisons

[[link removed]] is

cited as destructive to the lives of New York City residents.

The People’s Bank Act

[[link removed]] would

greatly increase the transparency of where the city banks and where it

invests the public’s money. It would require the city to publicize

a quarterly summary of its bank accounts

[[link removed]],

including balances and fees charged.

The city’s Committee on Finance held hearings

[[link removed]] on

the legislation in April. It is still listed as being considered

by the Committee

[[link removed]].

Bullish on Reform

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D), who worked as a banking executive

[[link removed]] before

her political career, has not made a public statement about whether

she supports the New York Public Banking Act. Nor has Mayor-elect Eric

Adams (D) indicated whether he supports the People’s Bank Act

(though he has spoken highly of opening up New York to cryptocurrency

and has said he will accept his first three city paychecks in Bitcoin

[[link removed]]).

But backers remain upbeat, in part because of New York’s slow

COVID-19 recovery.

“The momentum is building,” Morrison said. “We are really

excited about it, and we think this is the year for sure. There is

definitely a groundswell.”

When asked if he would bet money that the next public bank would be in

New York State, Morrison did not miss a beat.

“I would be all in. We would be all in. In fact, we are all in on

this campaign.”

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV