| From | Harriet and Stephen, Anthropocene Alliance <[email protected]> |

| Subject | A River with Rights |

| Date | October 28, 2021 4:57 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[link removed] [[link removed]]

A River with Rights

Story by Kerri McLean

Photographs by Todd Stewart

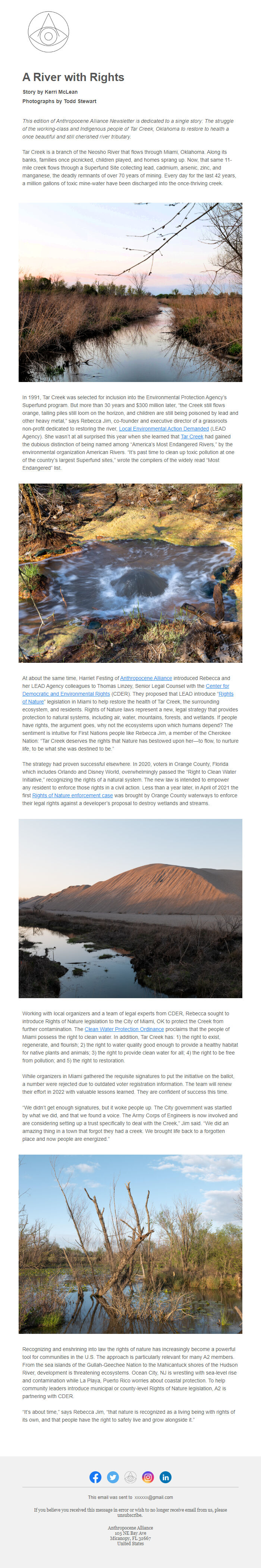

This edition of Anthropocene Alliance Newsletter is dedicated to a single story: The struggle of the working-class and Indigenous people of Tar Creek, Oklahoma to restore to health a once beautiful and still cherished river tributary.

Tar Creek is a branch of the Neosho River that flows through Miami, Oklahoma. Along its banks, families once picnicked, children played, and homes sprang up. Now, that same 11-mile creek flows through a Superfund Site collecting lead, cadmium, arsenic, zinc, and manganese, the deadly remnants of over 70 years of mining. Every day for the last 42 years, a million gallons of toxic mine-water have been discharged into the once-thriving creek.

In 1991, Tar Creek was selected for inclusion into the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program. But more than 30 years and $300 million later, “the Creek still flows orange, tailing piles still loom on the horizon, and children are still being poisoned by lead and other heavy metal,” says Rebecca Jim, co-founder and executive director of a grassroots non-profit dedicated to restoring the river, Local Environmental Action Demanded [[link removed]] (LEAD Agenc y) . She wasn’t at all surprised this year when she learned that Tar Creek [[link removed]] had gained the dubious distinction of being named among “America’s Most Endangered Rivers,” by the environmental organization American Rivers. “It’s past time to clean up toxic pollution at one of the country’s largest Superfund sites,” wrote the compilers of the widely read “Most Endangered” list.

[[link removed]]

At about the same time, Harriet Festing of Anthropocene Alliance [[link removed]] introduced Rebecca and her LEAD Agency colleagues to Thomas Linzey, Senior Legal Counsel with the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights [[link removed]] (CDER). They proposed that LEAD introduce “ Rights of Nature [[link removed]] ” legislation in Miami to help restore the health of Tar Creek, the surrounding ecosystem, and residents. Rights of Nature laws represent a new, legal strategy that provides protection to natural systems, including air, water, mountains, forests, and wetlands. If people have rights, the argument goes, why not the ecosystems upon which humans depend? The sentiment is intuitive for First Nations people like Rebecca Jim, a member of the Cherokee Nation: “Tar Creek deserves the rights that Nature has bestowed upon her—to flow, to nurture life, to be what she was destined to be.”

The strategy had proven successful elsewhere. In 2020, voters in Orange County, Florida which includes Orlando and Disney World, overwhelmingly passed the “Right to Clean Water Initiative,” recognizing the rights of a natural system. The new law is intended to empower any resident to enforce those rights in a civil action. Less than a year later, in April of 2021 the first Rights of Nature enforcement case [[link removed]] was brought by Orange County waterways to enforce their legal rights against a developer’s proposal to destroy wetlands and streams.

[[link removed]]

Working with local organizers and a team of legal experts from CDER, Rebecca sought to introduce Rights of Nature legislation to the City of Miami, OK to protect the Creek from further contamination. The Clean Water Protection Ordinance [[link removed]] proclaims that the people of Miami possess the right to clean water. In addition, Tar Creek has: 1) the right to exist, regenerate, and flourish; 2) the right to water quality good enough to provide a healthy habitat for native plants and animals; 3) the right to provide clean water for all; 4) the right to be free from pollution; and 5) the right to restoration.

While organizers in Miami gathered the requisite signatures to put the initiative on the ballot, a number were rejected due to outdated voter registration information. The team will renew their effort in 2022 with valuable lessons learned. They are confident of success this time.

“We didn’t get enough signatures, but it woke people up. The City government was startled by what we did, and that we found a voice. The Army Corps of Engineers is now involved and are considering setting up a trust specifically to deal with the Creek,” Jim said. “We did an amazing thing in a town that forgot they had a creek. We brought life back to a forgotten place and now people are energized.”

[[link removed]]

Recognizing and enshrining into law the rights of nature has increasingly become a powerful tool for communities in the U.S. The approach is particularly relevant for many A2 members. From the sea islands of the Gullah-Geechee Nation to the Mahicantuck shores of the Hudson River, development is threatening ecosystems. Ocean City, NJ is wrestling with sea-level rise and contamination while La Playa, Puerto Rico worries about coastal protection. To help community leaders introduce municipal or county-level Rights of Nature legislation, A2 is partnering with CDER.

“It’s about time,” says Rebecca Jim, “that nature is recognized as a living being with rights of its own, and that people have the right to safely live and grow alongside it.”

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

This email was sent to [email protected] you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

Anthropocene Alliance

105 NE Bay Ave

Micanopy, FL 32667

United States

A River with Rights

Story by Kerri McLean

Photographs by Todd Stewart

This edition of Anthropocene Alliance Newsletter is dedicated to a single story: The struggle of the working-class and Indigenous people of Tar Creek, Oklahoma to restore to health a once beautiful and still cherished river tributary.

Tar Creek is a branch of the Neosho River that flows through Miami, Oklahoma. Along its banks, families once picnicked, children played, and homes sprang up. Now, that same 11-mile creek flows through a Superfund Site collecting lead, cadmium, arsenic, zinc, and manganese, the deadly remnants of over 70 years of mining. Every day for the last 42 years, a million gallons of toxic mine-water have been discharged into the once-thriving creek.

In 1991, Tar Creek was selected for inclusion into the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program. But more than 30 years and $300 million later, “the Creek still flows orange, tailing piles still loom on the horizon, and children are still being poisoned by lead and other heavy metal,” says Rebecca Jim, co-founder and executive director of a grassroots non-profit dedicated to restoring the river, Local Environmental Action Demanded [[link removed]] (LEAD Agenc y) . She wasn’t at all surprised this year when she learned that Tar Creek [[link removed]] had gained the dubious distinction of being named among “America’s Most Endangered Rivers,” by the environmental organization American Rivers. “It’s past time to clean up toxic pollution at one of the country’s largest Superfund sites,” wrote the compilers of the widely read “Most Endangered” list.

[[link removed]]

At about the same time, Harriet Festing of Anthropocene Alliance [[link removed]] introduced Rebecca and her LEAD Agency colleagues to Thomas Linzey, Senior Legal Counsel with the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights [[link removed]] (CDER). They proposed that LEAD introduce “ Rights of Nature [[link removed]] ” legislation in Miami to help restore the health of Tar Creek, the surrounding ecosystem, and residents. Rights of Nature laws represent a new, legal strategy that provides protection to natural systems, including air, water, mountains, forests, and wetlands. If people have rights, the argument goes, why not the ecosystems upon which humans depend? The sentiment is intuitive for First Nations people like Rebecca Jim, a member of the Cherokee Nation: “Tar Creek deserves the rights that Nature has bestowed upon her—to flow, to nurture life, to be what she was destined to be.”

The strategy had proven successful elsewhere. In 2020, voters in Orange County, Florida which includes Orlando and Disney World, overwhelmingly passed the “Right to Clean Water Initiative,” recognizing the rights of a natural system. The new law is intended to empower any resident to enforce those rights in a civil action. Less than a year later, in April of 2021 the first Rights of Nature enforcement case [[link removed]] was brought by Orange County waterways to enforce their legal rights against a developer’s proposal to destroy wetlands and streams.

[[link removed]]

Working with local organizers and a team of legal experts from CDER, Rebecca sought to introduce Rights of Nature legislation to the City of Miami, OK to protect the Creek from further contamination. The Clean Water Protection Ordinance [[link removed]] proclaims that the people of Miami possess the right to clean water. In addition, Tar Creek has: 1) the right to exist, regenerate, and flourish; 2) the right to water quality good enough to provide a healthy habitat for native plants and animals; 3) the right to provide clean water for all; 4) the right to be free from pollution; and 5) the right to restoration.

While organizers in Miami gathered the requisite signatures to put the initiative on the ballot, a number were rejected due to outdated voter registration information. The team will renew their effort in 2022 with valuable lessons learned. They are confident of success this time.

“We didn’t get enough signatures, but it woke people up. The City government was startled by what we did, and that we found a voice. The Army Corps of Engineers is now involved and are considering setting up a trust specifically to deal with the Creek,” Jim said. “We did an amazing thing in a town that forgot they had a creek. We brought life back to a forgotten place and now people are energized.”

[[link removed]]

Recognizing and enshrining into law the rights of nature has increasingly become a powerful tool for communities in the U.S. The approach is particularly relevant for many A2 members. From the sea islands of the Gullah-Geechee Nation to the Mahicantuck shores of the Hudson River, development is threatening ecosystems. Ocean City, NJ is wrestling with sea-level rise and contamination while La Playa, Puerto Rico worries about coastal protection. To help community leaders introduce municipal or county-level Rights of Nature legislation, A2 is partnering with CDER.

“It’s about time,” says Rebecca Jim, “that nature is recognized as a living being with rights of its own, and that people have the right to safely live and grow alongside it.”

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

This email was sent to [email protected] you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

Anthropocene Alliance

105 NE Bay Ave

Micanopy, FL 32667

United States

Message Analysis

- Sender: Anthropocene Alliance

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- EveryAction