| From | Counter Extremism Project <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast |

| Date | October 26, 2021 7:01 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

October marks seven years since the United States first began providing

equipment and air support to the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), and

<[link removed]>

<[link removed]>

Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast

Read Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast by clicking here

<[link removed]>.

Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast

By Gregory Waters

October marks seven years since the United States first began providing

<[link removed]> equipment and air

support to the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), and later to their

umbrella organization the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in their anti-ISIS

campaign in northeast Syria. After the fall of ISIS’s so-called caliphate, the

U.S. government has continued to provide military support to these institutions

and their new political body—the Autonomous Administration of Northeast

Syria—conducting joint counter-ISIS operations in an attempt to end the ongoing

insurgency in the region. Recentreporting

<[link removed]>

on northeast Syria has highlighted the reduction in ISIS attacks and boasted

of a “return to normalcy” thanks to these security efforts. However, such

reporting is misleading and relies on cherry-picked data that assesses ISIS’s

strength purely through the number of reported attacks and uncritically sharing

media statements from Kurdish leaders.

A more compressive examination of the region presents a starkly different

picture, one in which ISIS is entrenching itself among the disenfranchised

communities of internally displaced people (IDPs), retains extensive freedom of

movement across the northeast’s borders with Iraq and regime-held Syria, and

conducts widespread financing and logistical operations. Much of this

resiliency is due to the worsening economic situation in the northeast, which

has caused a steep rise in smuggling, deepened distrust between locals and the

Autonomous Administration, and left young men susceptible to ISIS recruitment.

The situation is so bad now that young men are fleeing the region en masse,

risking the deadly smuggling routes to Europe for the chance at a future.

Rather than focus on maintaining the status quo, U.S. policy should be enhanced

to better address these non-military aspects of the ISIS insurgency and

roll-back the impending crises in the northeast.

Sheep as the New Oil

The recent capture

<[link removed]>

of ISIS’s head of finance by Turkish forces in northwest Syria has brought

renewed attention to ISIS financial networks. But security analyst Alex Almeida

<[link removed]> warns that, “His capture is likely not a

big deal. Local cells in Iraq and Syria can mostly self-finance, and ISIS

probably has several deputies that can take over the larger international

finance networks if that’s what he was still overseeing.” This devolution of

financing to the local level is precisely what has been observed in central and

northeast Syria, and it has allowed ISIS to remain resilient and regrow its

networks.

The kidnapping

<[link removed]>

of 60 civilians in eastern Hama on April 6, 2021, while shocking in its

brazenness, underscored the growing reality of ISIS operations in this

under-studied region of central Syria. Nearly all of the civilians were

released in a quickly arranged prisoner swap that saw the family members of

local ISIS fighters freed from the nearby regime prison in Salamiyah. This

prisoner exchange further supports regime claims that most ISIS fighters who

have been operating in east Hama for the past year are locals. ISIS has taken

advantage of these cells’ local knowledge in eastern Hama to bolster its

broader insurgency across Syria.

Source: Newslines Institute for Strategy and Policy

<[link removed]>

Based on local reporting and interviews conducted by this author, it appears

that ISIS has used its presence in eastern Hama and the area bordering southern

Raqqa and southern Aleppo to conduct widespread smuggling and fundraising

operations. Cells in these areas steal sheep from locals and either use them to

sustain themselves or smuggle them across the Euphrates River into northern

Raqqa. In areas controlled by the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF),

ISIS members posing as civilians sell the sheep on the open market, to the

Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) (the U.S.-designated terrorist group affiliated

with the SDF), or smuggle them across the Iraqi border.

The first major signs of this financing operation came in early 2021, when a

regime officer based in eastern Hama told this author that “hundreds” of sheep

were disappearing every week. According to the officer, locals were

increasingly complaining to security forces that their flocks were being

stolen, but neither locals nor security forces were able to locate any of the

sheep.

Local reporting has hinted at ISIS’s operation, though not to the degree the

officer claimed. Attacks on civilians in this rural agricultural area increased

significantly in February and March 2021. Most news reports spoke of ISIS mines

intentionally laid in grazing areas and along roads that left dozens dead or

wounded every month. However, there have also been at least 23 publicly

reported attacks on shepherds in these areas since ISIS first re-emerged in

eastern Hama in mid-2020. One of the group’s first major attacks in the

governorate took place in a remote village. ISIS stole the villagers’ sheep,

killing one civilian and those animals they could not take with them. Two

months later, in September, militants killed 12 shepherds and carted away their

entire flock. In November 2020, local security forces clashed with ISIS after

coming across what they referred to as an “ISIS sheep transport” near the major

highway connecting east Hama with Raqqa.

On multiple occasions this year, shepherds have been found executed with

gunshots to their heads in eastern Hama, southern Aleppo, and southern Raqqa.

The situation became so bad in eastern Hama that Syrian regime security forces,

who for months had been conducting “sweeping operations” to try and dislodge

insurgents, began focusing instead on guarding shepherds. This new policy

coincided with a sharp drop in ISIS activity in the province in general. The

regime officer claims that by late June the cells active in the area had all

left, as they could no longer easily prey on the herds.

However, it appears that these or other cells renewed their sheep thieving

operations within weeks, this time focusing on the nearby southern Raqqa

countryside. Reports on local Facebook pages of attacks on shepherds there

began trickling in throughout July and August and then surged in September when

militants kidnapped, killed, or attacked shepherds at least once each week.

This activity is not confined to the regime-held parts of Syria either,

occurring at a smaller level across the SDF-held northeast as well. On two

occasions in the first week of October, locals reported online that

“unidentified militants” stole dozens of sheep from two villages outside the

city of Raqqa. Hassan, a farmer and sheep trader from Raqqa, told this author

that in such cases the stolen sheep are often either smuggled into Iraq or

south across the “border” to regime-held areas to be sold in the markets where

locals would be unaware of their illicit origins.

In late May, shortly after the aforementioned regime officer spoke of the

sheep thefts in Hama, a local researcher in north Raqqa told this author that

as many as 23,000 sheep had been smuggled into the SDF-held regions from

southern Raqqa during the first few months of 2021. This massive movement of

sheep came amid a surge in locals fleeing widespread ISIS activity across

southern Raqqa and eastern Hama.

Officials from the SDF and Asayish (the Administration’s internal security

force) in Raqqa told this author in May that ISIS militants, disguised as

civilians, are regularly using both the official and unofficial border

crossings to move between regime- and SDF-held Raqqa. Terrorizing locals in

regime areas not only allows militants to steal valuable goods, but also drives

more people from their homes, increasing the IDP flow across these

difficult-to-secure border zones and providing additional cover for ISIS

movement.

A United Nations Transit Point Monitoring report from January

<[link removed]>

2021 claimed that in a two-week period more than 16,000 people had crossed

into SDF-held north Raqqa using just the three official crossings. IDP movement

reached a six-month high in March before dropping over the summer, according to

Administration leaders in Raqqa. These numbers do not account for the plethora

of unofficial crossings regularly used by both locals and ISIS, but the

reported surge and drop in IDP movement coincides with a similar pattern of

ISIS activity in east Hama and south Raqqa.

All of this points to a sustained supply and fundraising operation conducted

by ISIS cells in both regime- and SDF-held Syria, exploiting the embedded

underground economy of the region. Hassan maintains that sheep smuggling does

not account for most of ISIS’s new revenue. He points instead to the group’s

extortion of businesses in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor and the protection fees it

collects from truckers carrying oil and other goods between the northeast and

western Syria. However, throughout early 2021, sheep were selling for around

7,500 Syrian pounds in Raqqa, meaning that ISIS could easily be raising

millions of Syrian pounds every month solely through this enterprise.

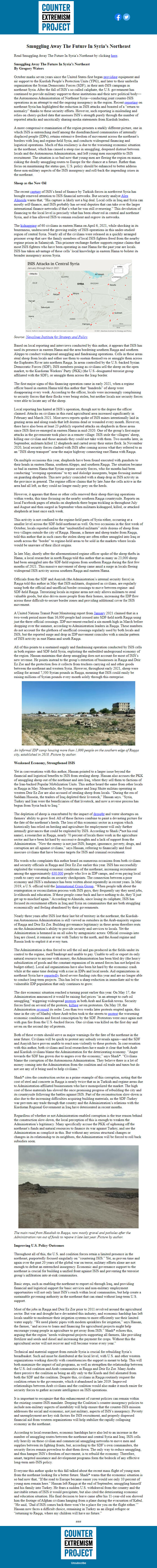

An informal IDP camp housing more than 1,000 people on the southern edge of

Raqqa city, established in 2018. Picture by author.

Weakened Economy, Strengthened ISIS

Yet in conversations with this author, Hassan pointed to a larger issue beyond

the financial and logistical benefits to ISIS from stealing sheep. Hassan also

accuses the PKK of smuggling sheep out of the northeast and into Iraq, where

they sell them to factions of the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Units. This

author heard the same from other locals in Raqqa in May. Meanwhile, the Syrian

regime and Iraqi Shiite militias operating in western Deir Ez Zor are also

accused of stealing sheep from locals. “During the era of Saddam Hussein, the

traders of Iraq depleted their livestock,” Hassan says. “Syria, Turkey and Iran

were the beneficiaries of that livestock, and now a reverse process has begun

from Syria back to Iraq.”

The depletion of sheep is exacerbated by the impact of drought

<[link removed]> and water shortages

on farmers’ ability to grow feed. All of these factors combine to paint a

devasting picture for the fate of the northeast’s herds. The loss of this

economic sector in a region which historically has relied on herding and

agriculture for employment will only further intensify grievances that could be

exploited by ISIS. According to Shadi (*not his real name), a researcher in

Raqqa, nearly 70 percent of locals there work in the agriculture sector and

have been hit hard by successive droughts and a lack of support from the

Administration. “Now the enemy is not just ISIS; hunger, ignorance, poverty,

drugs, and corruption are all against civilians,” says Hassan, referring to

financially and food insecure civilians that have become targets for ISIS and

criminal recruitment.

His words echo complaints this author heard on numerous occasions from both

civilians and security officials in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor earlier this year.

ISIS has successfully exploited the worsening economic conditions of the

northeast, increasing recruitment among the approximately 630,000

<[link removed]>

people who live in IDP camps, and even paying local youth to carry out attacks

on security checkpoints. The connection between a poor economy and ISIS’s

endurance has been written about repeatedly in recent years. In May 2019, a

U.S. official told the International Crisis Group

<[link removed]>

, “When people talk about the reintegration or reconciliation process with ISIS

guys, they frequently say they need jobs, livelihoods and education. If these

people come back and have nothing to do, they’ll just get up to mischief

again.” According to Almeida, since losing its caliphate, ISIS has focused its

recruitment efforts in Iraq and Syria on communities that are both struggling

economically and feeling abandoned by their governments.

Nearly three years after ISIS lost their last bit of territory in the

northeast, the Kurdish-run Autonomous Administration is still viewed as

outsiders in the Arab-majority regions of Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor. Building

governance legitimacy in these areas therefore rests on the Administration’s

ability to provide security and services to locals. Yet the Administration is

hemmed in on all sides by antagonistic actors: Official crossings into Iraq are

closed, it remains at war with Turkey to the north, and the Assad regime and

Russia look to exploit it at every turn.

The Administration is thus forced to sell the oil and gas produced in the

fields under its control to the regime, itself bankrupt and unable to pay.

Unable to sell or export its only natural resource to anyone with money, the

Administration has been bled dry (the heavy subsidization of goods and the

constant expansion of its armed forces has not helped its budget either). Local

aid organizations have also been hit hard by the economic crash while at the

same time dealing with a rise in IDPs and local needs. Aid organizations in

northeast Syria have reportedly

<[link removed]>

faced severe funding cuts this year and are no longer able to conduct

long-term projects. This has led to a sharp reduction in immediate aid to the

vulnerable IDP population that only continues to grow.

The dire economic situation reached a turning point earlier this year. On May

17, the Administration announced it would be raising fuel prices “in an attempt

to curb oil smuggling,” triggering widespread protests

<[link removed]>

in both Arab and Kurdish towns. Security forces fired on several of the

protests, killing

<[link removed]>

seven protestors. On May 19, the Administration reversed

<[link removed]>

its order. Less than two weeks later protests erupted again, this time in the

city of Manbij where Arab tribes took to the streets to protest

<[link removed]>

the worsening economic conditions and forced conscription by the SDF.

Protestors were once again met with gun fire from the U.S.-backed forces. One

civilian was killed on the first day and seven on the second day of protests.

Both of these events should serve as major warnings for the fate of the

northeast in the near future. Civilians will be quick to protest any subsidy

reversals again—and the SDF and Asayish have proven unable to react

non-violently to these protests. In conversation with this author, both

civilians and local researchers have made it clear that both Arab and Kurdish

civilians blame the Administration for the deteriorating economy. “Anger

towards the SDF has grown due to angers over the economy,” says Shadi*.

“Civilians blame the corruption of the Autonomous Administration. They believe

there is a lot of money coming into the Administration from the coalition and

oil trade and taxes but do not see any of it being used to help civilians.”

Shadi* cites the construction sector as a prime example of this corruption,

noting that the cost of steel and concrete in Raqqa is nearly twice that as in

Turkish and regime areas due to Administration-affiliated businessmen who have

monopolized the market. The high cost of these materials has slowed the once

promising progress of rebuilding the city and its countryside following the

battles against ISIS. Part of the reconstruction slow-down is also due to the

increasing difficulties acquiring building materials, as the SDF-Turkey war

prevents any trade through that country and the Administration’s relations with

the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq have deteriorated in recent months.

Regardless of whether or not Administration-enabled corruption is the true

reason behind the construction slow-down, the local perception of this is

enough to weaken the Administration’s legitimacy. Many specifically accuse the

PKK of siphoning off the northeast’s funds and natural resources to finance its

war against Turkey, and see the Administration as complicit in this. But

without any serious structural changes or changes in its relationship to its

neighbors, the Administration will be forced to roll back subsidies soon.

The main road from Hasakah to Raqqa, now mostly gravel and potholes after the

Administration ran out of funds to repave it late last year. Picture by author.

Improving U.S. Policy Outcomes

Throughout all of this, the U.S. and coalition forces retain a limited

presence in the northeast, purportedly focused singularly on “countering ISIS.”

Yet, as proven time and again over the past 20 years of the global war on

terror, military efforts alone are not enough to defeat an entrenched

insurgency. Economic and governance support to the northeast is crucial for

building a unified front against ISIS and preventing the terrorist group’s

infiltration into at-risk communities.

Basic steps, such as enabling the northeast to export oil through Iraq, and

providing financial and logistical support for basic services and non-military

employment opportunities will not only limit ISIS’s reach within local

communities, but help create a sustainable governing authority in the northeast

that can stand without long-term U.S. support.

Most of the jobs in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor prior to 2011 revolved around the

agricultural sector. But war and drought have devastated this industry, and

economic hardship has left locals unable to modernize their irrigation systems

to more efficiently use their limited water supply. “We need plastic pipes with

modern sprinklers for irrigation,” says Hassan, the farmer, “and access to

loans and financing for agricultural projects might help encourage young people

in agriculture to get away from ISIS.” Shadi* echoes this, arguing that the

region “needs widespread projects supporting all farmers, like providing

fertilizer and seeds and diesel and increasing the payment for crops. Without

this the agricultural sector will not recover and will become worse every year.”

Technical and material support from outside Syria is crucial for rebuilding

Syria’s breadbasket. Such aid must be distributed at the local level, with U.S.

and other western organizations working directly with constituencies the

support is meant to help. This will both maximize the impact of aid programs,

as well as strengthen the relationship between the U.S.-led coalition and Arab

communities in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor. Many Arabs there perceive the coalition

as being an ally only to the Kurds and feel alienated from both the SDF and the

coalition. Despite this, civilians in Raqqa routinely request the coalition

return to the governorate, which it abandoned in late 2019. Improved

relationships between Arab civilians and the coalition would also make it much

easier for security forces to gather accurate intelligence on ISIS operations.

It is important to recognize that this enhancement of current policies can

remain within the existing counter-ISIS mandate. Deeping the Coalition’s

counter-insurgency policies to include non-military aspects of instability will

help ensure that the counter-ISIS mission addresses the social and economic,

not just military, aspects of ISIS’s insurgency. Poverty and unemployment are

key risk factors for ISIS recruitment, and properly dispersed financial aid

from western organizations will help stabilize the rapidly collapsing economy

in the northeast.

According to local researchers, economic hardships have also led to an

increase in the number of smuggling routes between the northeast and central

Syria and Iraq. ISIS cells rely heavily on these civilian and commercial

smuggling networks to move men and supplies between its fighting fronts, but,

according to the SDF’s own commanders, the security forces remain powerless to

shut them down. The only way to reduce smuggling, and thus hamper ISIS’s

freedom of movement, is to rebuild the economy. Therefore, smart, targeted

assistance and development programs form the bedrock of any effective long-term

anti-ISIS policy.

Everyone this author spoke to this fall talked about the recent mass flight of

young men from the northeast looking for a better future. Shadi* warns that the

economic situation is so bad now that, “If the road to Europe became easier you

would see only 10 percent of young men remain here.” Hassan left Raqqa at the

end of September, smuggling himself and his family into Turkey. He fears a

sudden U.S. withdrawal from the country and the inevitable return of ISIS it

would precipitate, but also cited the deteriorating economic and education

situation. His final decision to leave came after his 11-year-old son showed

him the footage of Afghan civilians hanging from a plane during the evacuation

of Kabul. “He said, ‘Dad if ISIS comes back there won’t be a place for you on

the flight either.’” Hassan now faces a difficult choice, remaining in Turkey

as an illegal refugee or “returning to Raqqa, where my children will have no

future.”

###

Unsubscribe

<[link removed]>

equipment and air support to the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), and

<[link removed]>

<[link removed]>

Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast

Read Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast by clicking here

<[link removed]>.

Smuggling Away The Future In Syria’s Northeast

By Gregory Waters

October marks seven years since the United States first began providing

<[link removed]> equipment and air

support to the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), and later to their

umbrella organization the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in their anti-ISIS

campaign in northeast Syria. After the fall of ISIS’s so-called caliphate, the

U.S. government has continued to provide military support to these institutions

and their new political body—the Autonomous Administration of Northeast

Syria—conducting joint counter-ISIS operations in an attempt to end the ongoing

insurgency in the region. Recentreporting

<[link removed]>

on northeast Syria has highlighted the reduction in ISIS attacks and boasted

of a “return to normalcy” thanks to these security efforts. However, such

reporting is misleading and relies on cherry-picked data that assesses ISIS’s

strength purely through the number of reported attacks and uncritically sharing

media statements from Kurdish leaders.

A more compressive examination of the region presents a starkly different

picture, one in which ISIS is entrenching itself among the disenfranchised

communities of internally displaced people (IDPs), retains extensive freedom of

movement across the northeast’s borders with Iraq and regime-held Syria, and

conducts widespread financing and logistical operations. Much of this

resiliency is due to the worsening economic situation in the northeast, which

has caused a steep rise in smuggling, deepened distrust between locals and the

Autonomous Administration, and left young men susceptible to ISIS recruitment.

The situation is so bad now that young men are fleeing the region en masse,

risking the deadly smuggling routes to Europe for the chance at a future.

Rather than focus on maintaining the status quo, U.S. policy should be enhanced

to better address these non-military aspects of the ISIS insurgency and

roll-back the impending crises in the northeast.

Sheep as the New Oil

The recent capture

<[link removed]>

of ISIS’s head of finance by Turkish forces in northwest Syria has brought

renewed attention to ISIS financial networks. But security analyst Alex Almeida

<[link removed]> warns that, “His capture is likely not a

big deal. Local cells in Iraq and Syria can mostly self-finance, and ISIS

probably has several deputies that can take over the larger international

finance networks if that’s what he was still overseeing.” This devolution of

financing to the local level is precisely what has been observed in central and

northeast Syria, and it has allowed ISIS to remain resilient and regrow its

networks.

The kidnapping

<[link removed]>

of 60 civilians in eastern Hama on April 6, 2021, while shocking in its

brazenness, underscored the growing reality of ISIS operations in this

under-studied region of central Syria. Nearly all of the civilians were

released in a quickly arranged prisoner swap that saw the family members of

local ISIS fighters freed from the nearby regime prison in Salamiyah. This

prisoner exchange further supports regime claims that most ISIS fighters who

have been operating in east Hama for the past year are locals. ISIS has taken

advantage of these cells’ local knowledge in eastern Hama to bolster its

broader insurgency across Syria.

Source: Newslines Institute for Strategy and Policy

<[link removed]>

Based on local reporting and interviews conducted by this author, it appears

that ISIS has used its presence in eastern Hama and the area bordering southern

Raqqa and southern Aleppo to conduct widespread smuggling and fundraising

operations. Cells in these areas steal sheep from locals and either use them to

sustain themselves or smuggle them across the Euphrates River into northern

Raqqa. In areas controlled by the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF),

ISIS members posing as civilians sell the sheep on the open market, to the

Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) (the U.S.-designated terrorist group affiliated

with the SDF), or smuggle them across the Iraqi border.

The first major signs of this financing operation came in early 2021, when a

regime officer based in eastern Hama told this author that “hundreds” of sheep

were disappearing every week. According to the officer, locals were

increasingly complaining to security forces that their flocks were being

stolen, but neither locals nor security forces were able to locate any of the

sheep.

Local reporting has hinted at ISIS’s operation, though not to the degree the

officer claimed. Attacks on civilians in this rural agricultural area increased

significantly in February and March 2021. Most news reports spoke of ISIS mines

intentionally laid in grazing areas and along roads that left dozens dead or

wounded every month. However, there have also been at least 23 publicly

reported attacks on shepherds in these areas since ISIS first re-emerged in

eastern Hama in mid-2020. One of the group’s first major attacks in the

governorate took place in a remote village. ISIS stole the villagers’ sheep,

killing one civilian and those animals they could not take with them. Two

months later, in September, militants killed 12 shepherds and carted away their

entire flock. In November 2020, local security forces clashed with ISIS after

coming across what they referred to as an “ISIS sheep transport” near the major

highway connecting east Hama with Raqqa.

On multiple occasions this year, shepherds have been found executed with

gunshots to their heads in eastern Hama, southern Aleppo, and southern Raqqa.

The situation became so bad in eastern Hama that Syrian regime security forces,

who for months had been conducting “sweeping operations” to try and dislodge

insurgents, began focusing instead on guarding shepherds. This new policy

coincided with a sharp drop in ISIS activity in the province in general. The

regime officer claims that by late June the cells active in the area had all

left, as they could no longer easily prey on the herds.

However, it appears that these or other cells renewed their sheep thieving

operations within weeks, this time focusing on the nearby southern Raqqa

countryside. Reports on local Facebook pages of attacks on shepherds there

began trickling in throughout July and August and then surged in September when

militants kidnapped, killed, or attacked shepherds at least once each week.

This activity is not confined to the regime-held parts of Syria either,

occurring at a smaller level across the SDF-held northeast as well. On two

occasions in the first week of October, locals reported online that

“unidentified militants” stole dozens of sheep from two villages outside the

city of Raqqa. Hassan, a farmer and sheep trader from Raqqa, told this author

that in such cases the stolen sheep are often either smuggled into Iraq or

south across the “border” to regime-held areas to be sold in the markets where

locals would be unaware of their illicit origins.

In late May, shortly after the aforementioned regime officer spoke of the

sheep thefts in Hama, a local researcher in north Raqqa told this author that

as many as 23,000 sheep had been smuggled into the SDF-held regions from

southern Raqqa during the first few months of 2021. This massive movement of

sheep came amid a surge in locals fleeing widespread ISIS activity across

southern Raqqa and eastern Hama.

Officials from the SDF and Asayish (the Administration’s internal security

force) in Raqqa told this author in May that ISIS militants, disguised as

civilians, are regularly using both the official and unofficial border

crossings to move between regime- and SDF-held Raqqa. Terrorizing locals in

regime areas not only allows militants to steal valuable goods, but also drives

more people from their homes, increasing the IDP flow across these

difficult-to-secure border zones and providing additional cover for ISIS

movement.

A United Nations Transit Point Monitoring report from January

<[link removed]>

2021 claimed that in a two-week period more than 16,000 people had crossed

into SDF-held north Raqqa using just the three official crossings. IDP movement

reached a six-month high in March before dropping over the summer, according to

Administration leaders in Raqqa. These numbers do not account for the plethora

of unofficial crossings regularly used by both locals and ISIS, but the

reported surge and drop in IDP movement coincides with a similar pattern of

ISIS activity in east Hama and south Raqqa.

All of this points to a sustained supply and fundraising operation conducted

by ISIS cells in both regime- and SDF-held Syria, exploiting the embedded

underground economy of the region. Hassan maintains that sheep smuggling does

not account for most of ISIS’s new revenue. He points instead to the group’s

extortion of businesses in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor and the protection fees it

collects from truckers carrying oil and other goods between the northeast and

western Syria. However, throughout early 2021, sheep were selling for around

7,500 Syrian pounds in Raqqa, meaning that ISIS could easily be raising

millions of Syrian pounds every month solely through this enterprise.

An informal IDP camp housing more than 1,000 people on the southern edge of

Raqqa city, established in 2018. Picture by author.

Weakened Economy, Strengthened ISIS

Yet in conversations with this author, Hassan pointed to a larger issue beyond

the financial and logistical benefits to ISIS from stealing sheep. Hassan also

accuses the PKK of smuggling sheep out of the northeast and into Iraq, where

they sell them to factions of the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Units. This

author heard the same from other locals in Raqqa in May. Meanwhile, the Syrian

regime and Iraqi Shiite militias operating in western Deir Ez Zor are also

accused of stealing sheep from locals. “During the era of Saddam Hussein, the

traders of Iraq depleted their livestock,” Hassan says. “Syria, Turkey and Iran

were the beneficiaries of that livestock, and now a reverse process has begun

from Syria back to Iraq.”

The depletion of sheep is exacerbated by the impact of drought

<[link removed]> and water shortages

on farmers’ ability to grow feed. All of these factors combine to paint a

devasting picture for the fate of the northeast’s herds. The loss of this

economic sector in a region which historically has relied on herding and

agriculture for employment will only further intensify grievances that could be

exploited by ISIS. According to Shadi (*not his real name), a researcher in

Raqqa, nearly 70 percent of locals there work in the agriculture sector and

have been hit hard by successive droughts and a lack of support from the

Administration. “Now the enemy is not just ISIS; hunger, ignorance, poverty,

drugs, and corruption are all against civilians,” says Hassan, referring to

financially and food insecure civilians that have become targets for ISIS and

criminal recruitment.

His words echo complaints this author heard on numerous occasions from both

civilians and security officials in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor earlier this year.

ISIS has successfully exploited the worsening economic conditions of the

northeast, increasing recruitment among the approximately 630,000

<[link removed]>

people who live in IDP camps, and even paying local youth to carry out attacks

on security checkpoints. The connection between a poor economy and ISIS’s

endurance has been written about repeatedly in recent years. In May 2019, a

U.S. official told the International Crisis Group

<[link removed]>

, “When people talk about the reintegration or reconciliation process with ISIS

guys, they frequently say they need jobs, livelihoods and education. If these

people come back and have nothing to do, they’ll just get up to mischief

again.” According to Almeida, since losing its caliphate, ISIS has focused its

recruitment efforts in Iraq and Syria on communities that are both struggling

economically and feeling abandoned by their governments.

Nearly three years after ISIS lost their last bit of territory in the

northeast, the Kurdish-run Autonomous Administration is still viewed as

outsiders in the Arab-majority regions of Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor. Building

governance legitimacy in these areas therefore rests on the Administration’s

ability to provide security and services to locals. Yet the Administration is

hemmed in on all sides by antagonistic actors: Official crossings into Iraq are

closed, it remains at war with Turkey to the north, and the Assad regime and

Russia look to exploit it at every turn.

The Administration is thus forced to sell the oil and gas produced in the

fields under its control to the regime, itself bankrupt and unable to pay.

Unable to sell or export its only natural resource to anyone with money, the

Administration has been bled dry (the heavy subsidization of goods and the

constant expansion of its armed forces has not helped its budget either). Local

aid organizations have also been hit hard by the economic crash while at the

same time dealing with a rise in IDPs and local needs. Aid organizations in

northeast Syria have reportedly

<[link removed]>

faced severe funding cuts this year and are no longer able to conduct

long-term projects. This has led to a sharp reduction in immediate aid to the

vulnerable IDP population that only continues to grow.

The dire economic situation reached a turning point earlier this year. On May

17, the Administration announced it would be raising fuel prices “in an attempt

to curb oil smuggling,” triggering widespread protests

<[link removed]>

in both Arab and Kurdish towns. Security forces fired on several of the

protests, killing

<[link removed]>

seven protestors. On May 19, the Administration reversed

<[link removed]>

its order. Less than two weeks later protests erupted again, this time in the

city of Manbij where Arab tribes took to the streets to protest

<[link removed]>

the worsening economic conditions and forced conscription by the SDF.

Protestors were once again met with gun fire from the U.S.-backed forces. One

civilian was killed on the first day and seven on the second day of protests.

Both of these events should serve as major warnings for the fate of the

northeast in the near future. Civilians will be quick to protest any subsidy

reversals again—and the SDF and Asayish have proven unable to react

non-violently to these protests. In conversation with this author, both

civilians and local researchers have made it clear that both Arab and Kurdish

civilians blame the Administration for the deteriorating economy. “Anger

towards the SDF has grown due to angers over the economy,” says Shadi*.

“Civilians blame the corruption of the Autonomous Administration. They believe

there is a lot of money coming into the Administration from the coalition and

oil trade and taxes but do not see any of it being used to help civilians.”

Shadi* cites the construction sector as a prime example of this corruption,

noting that the cost of steel and concrete in Raqqa is nearly twice that as in

Turkish and regime areas due to Administration-affiliated businessmen who have

monopolized the market. The high cost of these materials has slowed the once

promising progress of rebuilding the city and its countryside following the

battles against ISIS. Part of the reconstruction slow-down is also due to the

increasing difficulties acquiring building materials, as the SDF-Turkey war

prevents any trade through that country and the Administration’s relations with

the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq have deteriorated in recent months.

Regardless of whether or not Administration-enabled corruption is the true

reason behind the construction slow-down, the local perception of this is

enough to weaken the Administration’s legitimacy. Many specifically accuse the

PKK of siphoning off the northeast’s funds and natural resources to finance its

war against Turkey, and see the Administration as complicit in this. But

without any serious structural changes or changes in its relationship to its

neighbors, the Administration will be forced to roll back subsidies soon.

The main road from Hasakah to Raqqa, now mostly gravel and potholes after the

Administration ran out of funds to repave it late last year. Picture by author.

Improving U.S. Policy Outcomes

Throughout all of this, the U.S. and coalition forces retain a limited

presence in the northeast, purportedly focused singularly on “countering ISIS.”

Yet, as proven time and again over the past 20 years of the global war on

terror, military efforts alone are not enough to defeat an entrenched

insurgency. Economic and governance support to the northeast is crucial for

building a unified front against ISIS and preventing the terrorist group’s

infiltration into at-risk communities.

Basic steps, such as enabling the northeast to export oil through Iraq, and

providing financial and logistical support for basic services and non-military

employment opportunities will not only limit ISIS’s reach within local

communities, but help create a sustainable governing authority in the northeast

that can stand without long-term U.S. support.

Most of the jobs in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor prior to 2011 revolved around the

agricultural sector. But war and drought have devastated this industry, and

economic hardship has left locals unable to modernize their irrigation systems

to more efficiently use their limited water supply. “We need plastic pipes with

modern sprinklers for irrigation,” says Hassan, the farmer, “and access to

loans and financing for agricultural projects might help encourage young people

in agriculture to get away from ISIS.” Shadi* echoes this, arguing that the

region “needs widespread projects supporting all farmers, like providing

fertilizer and seeds and diesel and increasing the payment for crops. Without

this the agricultural sector will not recover and will become worse every year.”

Technical and material support from outside Syria is crucial for rebuilding

Syria’s breadbasket. Such aid must be distributed at the local level, with U.S.

and other western organizations working directly with constituencies the

support is meant to help. This will both maximize the impact of aid programs,

as well as strengthen the relationship between the U.S.-led coalition and Arab

communities in Raqqa and Deir Ez Zor. Many Arabs there perceive the coalition

as being an ally only to the Kurds and feel alienated from both the SDF and the

coalition. Despite this, civilians in Raqqa routinely request the coalition

return to the governorate, which it abandoned in late 2019. Improved

relationships between Arab civilians and the coalition would also make it much

easier for security forces to gather accurate intelligence on ISIS operations.

It is important to recognize that this enhancement of current policies can

remain within the existing counter-ISIS mandate. Deeping the Coalition’s

counter-insurgency policies to include non-military aspects of instability will

help ensure that the counter-ISIS mission addresses the social and economic,

not just military, aspects of ISIS’s insurgency. Poverty and unemployment are

key risk factors for ISIS recruitment, and properly dispersed financial aid

from western organizations will help stabilize the rapidly collapsing economy

in the northeast.

According to local researchers, economic hardships have also led to an

increase in the number of smuggling routes between the northeast and central

Syria and Iraq. ISIS cells rely heavily on these civilian and commercial

smuggling networks to move men and supplies between its fighting fronts, but,

according to the SDF’s own commanders, the security forces remain powerless to

shut them down. The only way to reduce smuggling, and thus hamper ISIS’s

freedom of movement, is to rebuild the economy. Therefore, smart, targeted

assistance and development programs form the bedrock of any effective long-term

anti-ISIS policy.

Everyone this author spoke to this fall talked about the recent mass flight of

young men from the northeast looking for a better future. Shadi* warns that the

economic situation is so bad now that, “If the road to Europe became easier you

would see only 10 percent of young men remain here.” Hassan left Raqqa at the

end of September, smuggling himself and his family into Turkey. He fears a

sudden U.S. withdrawal from the country and the inevitable return of ISIS it

would precipitate, but also cited the deteriorating economic and education

situation. His final decision to leave came after his 11-year-old son showed

him the footage of Afghan civilians hanging from a plane during the evacuation

of Kabul. “He said, ‘Dad if ISIS comes back there won’t be a place for you on

the flight either.’” Hassan now faces a difficult choice, remaining in Turkey

as an illegal refugee or “returning to Raqqa, where my children will have no

future.”

###

Unsubscribe

<[link removed]>

Message Analysis

- Sender: Counter Extremism Project

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Iterable