| From | Portside Culture <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Taking it to the street: Food vending during and after COVID-19 |

| Date | February 23, 2021 1:05 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[Curbside produce vendors often help communities that lack a

grocery store to maintain access to healthy, inexpensive food. But

long before the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile

produce sellers and other street food vendors to operate]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

TAKING IT TO THE STREET: FOOD VENDING DURING AND AFTER COVID-19

[[link removed]]

Catherine Brinkley

February 17, 2021

The Conversation

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ Curbside produce vendors often help communities that lack a grocery

store to maintain access to healthy, inexpensive food. But long before

the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile produce sellers

and other street food vendors to operate _

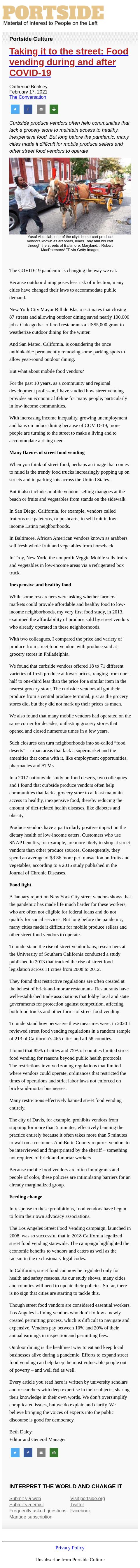

Yusuf Abdullah, one of the city’s horse-cart produce vendors known

as arabbers, leads Tony and his cart through the streets of Baltimore,

Maryland. , Robert MacPherson/AFP via Getty Images

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the way we eat.

Because outdoor dining poses less risk of infection, many cities have

changed their laws to accommodate public demand.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio estimates that closing 87 streets

and allowing outdoor dining saved nearly 100,000 jobs. Chicago has

offered restaurants a US$5,000 grant to weatherize outdoor dining for

the winter.

And San Mateo, California, is considering the once unthinkable:

permanently removing some parking spots to allow year-round outdoor

dining.

But what about mobile food vendors?

For the past 10 years, as a community and regional development

professor, I have studied how street vending provides an economic

lifeline for many people, particularly in low-income communities.

With increasing income inequality, growing unemployment and bans on

indoor dining because of COVID-19, more people are turning to the

street to make a living and to accommodate a rising need.

MANY FLAVORS OF STREET FOOD VENDING

When you think of street food, perhaps an image that comes to mind is

the trendy food trucks increasingly popping up on streets and in

parking lots across the United States.

But it also includes mobile vendors selling mangoes at the beach or

fruits and vegetables from stands on the sidewalk.

In San Diego, California, for example, vendors called fruteros use

paleteros, or pushcarts, to sell fruit in low-income Latino

neighborhoods.

In Baltimore, African American vendors known as arabbers sell fresh

whole fruit and vegetables from horseback.

In Troy, New York, the nonprofit Veggie Mobile sells fruits and

vegetables in low-income areas via a refrigerated box truck.

INEXPENSIVE AND HEALTHY FOOD

While some researchers were asking whether farmers markets could

provide affordable and healthy food to low-income neighborhoods, my

very first food study, in 2013, examined the affordability of produce

sold by street vendors who already operated in these neighborhoods.

With two colleagues, I compared the price and variety of produce from

street food vendors with produce sold at grocery stores in

Philadelphia.

We found that curbside vendors offered 18 to 71 different varieties of

fresh produce at lower prices, ranging from one-half to one-third less

than the price for a similar item in the nearest grocery store. The

curbside vendors all got their produce from a central produce

terminal, just as the grocery stores did, but they did not mark up

their prices as much.

We also found that many mobile vendors had operated on the same corner

for decades, outlasting grocery stores that opened and closed numerous

times in a few years.

Such closures can turn neighborhoods into so-called “food deserts”

– urban areas that lack a supermarket and the amenities that come

with it, like employment opportunities, pharmacies and ATMs.

In a 2017 nationwide study on food deserts, two colleagues and I found

that curbside produce vendors often help communities that lack a

grocery store to at least maintain access to healthy, inexpensive

food, thereby reducing the amount of diet-related health diseases,

like diabetes and obesity.

Produce vendors have a particularly positive impact on the dietary

health of low-income eaters. Customers who use SNAP benefits, for

example, are more likely to shop at street vendors than other produce

sources. Consequently, they spend an average of $3.86 more per

transaction on fruits and vegetables, according to a 2015 study

published in the Journal of Chronic Diseases.

FOOD FIGHT

A January report on New York City street vendors shows that the

pandemic has made life much harder for these workers, who are often

not eligible for federal loans and do not qualify for social services.

But long before the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile

produce sellers and other street food vendors to operate.

To understand the rise of street vendor bans, researchers at the

University of Southern California conducted a study published in 2013

that tracked the rise of street food legislation across 11 cities from

2008 to 2012.

They found that restrictive regulations are often created at the

behest of brick-and-mortar restaurants. Restaurants have

well-established trade associations that lobby local and state

governments for protection against competition, affecting both food

trucks and other forms of street food vending.

To understand how pervasive these measures were, in 2020 I reviewed

street food vending regulations in a random sample of 213 of

California’s 465 cities and all 58 counties.

I found that 85% of cities and 75% of counties limited street food

vending for reasons beyond public health protocols. The restrictions

involved zoning regulations that limited where vendors could operate,

ordinances that restricted the times of operations and strict labor

laws not enforced on brick-and-mortar businesses.

Many restrictions effectively banned street food vending entirely.

The city of Davis, for example, prohibits vendors from stopping for

more than 5 minutes, effectively banning the practice entirely because

it often takes more than 5 minutes to wait on a customer. And Butte

County requires vendors to be interviewed and fingerprinted by the

sheriff – something not required of brick-and-mortar workers.

Because mobile food vendors are often immigrants and people of color,

these policies are intimidating barriers for an already marginalized

group.

FEEDING CHANGE

In response to these prohibitions, food vendors have begun to form

their own advocacy associations.

The Los Angeles Street Food Vending campaign, launched in 2008, was so

successful that in 2018 California legalized street food vending

statewide. The campaign highlighted the economic benefits to vendors

and eaters as well as the racism in the exclusionary legal codes.

In California, street food can now be regulated only for health and

safety reasons. As our study shows, many cities and counties will need

to update their policies. So far, there is no sign that cities are

starting to tackle this.

Though street food vendors are considered essential workers, Los

Angeles is fining vendors who don’t follow a newly created

permitting process, which is difficult to navigate and expensive.

Vendors pay between 10% and 20% of their annual earnings in inspection

and permitting fees.

Outdoor dining is the healthiest way to eat and keep local businesses

alive during a pandemic. Efforts to expand street food vending can

help keep the most vulnerable people out of poverty – and well fed

as well.

Every article you read here is written by university scholars and

researchers with deep expertise in their subjects, sharing their

knowledge in their own words. We don’t oversimplify complicated

issues, but we do explain and clarify. We believe bringing the voices

of experts into the public discourse is good for democracy.

Beth Daley

Editor and General Manager

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit portside.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

grocery store to maintain access to healthy, inexpensive food. But

long before the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile

produce sellers and other street food vendors to operate]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

TAKING IT TO THE STREET: FOOD VENDING DURING AND AFTER COVID-19

[[link removed]]

Catherine Brinkley

February 17, 2021

The Conversation

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ Curbside produce vendors often help communities that lack a grocery

store to maintain access to healthy, inexpensive food. But long before

the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile produce sellers

and other street food vendors to operate _

Yusuf Abdullah, one of the city’s horse-cart produce vendors known

as arabbers, leads Tony and his cart through the streets of Baltimore,

Maryland. , Robert MacPherson/AFP via Getty Images

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the way we eat.

Because outdoor dining poses less risk of infection, many cities have

changed their laws to accommodate public demand.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio estimates that closing 87 streets

and allowing outdoor dining saved nearly 100,000 jobs. Chicago has

offered restaurants a US$5,000 grant to weatherize outdoor dining for

the winter.

And San Mateo, California, is considering the once unthinkable:

permanently removing some parking spots to allow year-round outdoor

dining.

But what about mobile food vendors?

For the past 10 years, as a community and regional development

professor, I have studied how street vending provides an economic

lifeline for many people, particularly in low-income communities.

With increasing income inequality, growing unemployment and bans on

indoor dining because of COVID-19, more people are turning to the

street to make a living and to accommodate a rising need.

MANY FLAVORS OF STREET FOOD VENDING

When you think of street food, perhaps an image that comes to mind is

the trendy food trucks increasingly popping up on streets and in

parking lots across the United States.

But it also includes mobile vendors selling mangoes at the beach or

fruits and vegetables from stands on the sidewalk.

In San Diego, California, for example, vendors called fruteros use

paleteros, or pushcarts, to sell fruit in low-income Latino

neighborhoods.

In Baltimore, African American vendors known as arabbers sell fresh

whole fruit and vegetables from horseback.

In Troy, New York, the nonprofit Veggie Mobile sells fruits and

vegetables in low-income areas via a refrigerated box truck.

INEXPENSIVE AND HEALTHY FOOD

While some researchers were asking whether farmers markets could

provide affordable and healthy food to low-income neighborhoods, my

very first food study, in 2013, examined the affordability of produce

sold by street vendors who already operated in these neighborhoods.

With two colleagues, I compared the price and variety of produce from

street food vendors with produce sold at grocery stores in

Philadelphia.

We found that curbside vendors offered 18 to 71 different varieties of

fresh produce at lower prices, ranging from one-half to one-third less

than the price for a similar item in the nearest grocery store. The

curbside vendors all got their produce from a central produce

terminal, just as the grocery stores did, but they did not mark up

their prices as much.

We also found that many mobile vendors had operated on the same corner

for decades, outlasting grocery stores that opened and closed numerous

times in a few years.

Such closures can turn neighborhoods into so-called “food deserts”

– urban areas that lack a supermarket and the amenities that come

with it, like employment opportunities, pharmacies and ATMs.

In a 2017 nationwide study on food deserts, two colleagues and I found

that curbside produce vendors often help communities that lack a

grocery store to at least maintain access to healthy, inexpensive

food, thereby reducing the amount of diet-related health diseases,

like diabetes and obesity.

Produce vendors have a particularly positive impact on the dietary

health of low-income eaters. Customers who use SNAP benefits, for

example, are more likely to shop at street vendors than other produce

sources. Consequently, they spend an average of $3.86 more per

transaction on fruits and vegetables, according to a 2015 study

published in the Journal of Chronic Diseases.

FOOD FIGHT

A January report on New York City street vendors shows that the

pandemic has made life much harder for these workers, who are often

not eligible for federal loans and do not qualify for social services.

But long before the pandemic, many cities made it difficult for mobile

produce sellers and other street food vendors to operate.

To understand the rise of street vendor bans, researchers at the

University of Southern California conducted a study published in 2013

that tracked the rise of street food legislation across 11 cities from

2008 to 2012.

They found that restrictive regulations are often created at the

behest of brick-and-mortar restaurants. Restaurants have

well-established trade associations that lobby local and state

governments for protection against competition, affecting both food

trucks and other forms of street food vending.

To understand how pervasive these measures were, in 2020 I reviewed

street food vending regulations in a random sample of 213 of

California’s 465 cities and all 58 counties.

I found that 85% of cities and 75% of counties limited street food

vending for reasons beyond public health protocols. The restrictions

involved zoning regulations that limited where vendors could operate,

ordinances that restricted the times of operations and strict labor

laws not enforced on brick-and-mortar businesses.

Many restrictions effectively banned street food vending entirely.

The city of Davis, for example, prohibits vendors from stopping for

more than 5 minutes, effectively banning the practice entirely because

it often takes more than 5 minutes to wait on a customer. And Butte

County requires vendors to be interviewed and fingerprinted by the

sheriff – something not required of brick-and-mortar workers.

Because mobile food vendors are often immigrants and people of color,

these policies are intimidating barriers for an already marginalized

group.

FEEDING CHANGE

In response to these prohibitions, food vendors have begun to form

their own advocacy associations.

The Los Angeles Street Food Vending campaign, launched in 2008, was so

successful that in 2018 California legalized street food vending

statewide. The campaign highlighted the economic benefits to vendors

and eaters as well as the racism in the exclusionary legal codes.

In California, street food can now be regulated only for health and

safety reasons. As our study shows, many cities and counties will need

to update their policies. So far, there is no sign that cities are

starting to tackle this.

Though street food vendors are considered essential workers, Los

Angeles is fining vendors who don’t follow a newly created

permitting process, which is difficult to navigate and expensive.

Vendors pay between 10% and 20% of their annual earnings in inspection

and permitting fees.

Outdoor dining is the healthiest way to eat and keep local businesses

alive during a pandemic. Efforts to expand street food vending can

help keep the most vulnerable people out of poverty – and well fed

as well.

Every article you read here is written by university scholars and

researchers with deep expertise in their subjects, sharing their

knowledge in their own words. We don’t oversimplify complicated

issues, but we do explain and clarify. We believe bringing the voices

of experts into the public discourse is good for democracy.

Beth Daley

Editor and General Manager

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit portside.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV