| From | AVAC <[email protected]> |

| Subject | COVID News Brief: The news you need to know |

| Date | February 10, 2021 10:27 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this email in your browser ([link removed])

AVAC's weekly COVID News Brief provides a curated perspective on what COVID news is worth your time.

"Researchers... are still learning about how the new variants behave. But ultimately the best way to stop a virus from evolving is to prevent it from spreading by whatever means are available. All the more reason, therefore, to vaccinate as quickly and as widely as possible.”

— Jon Cohen in Science ([link removed])

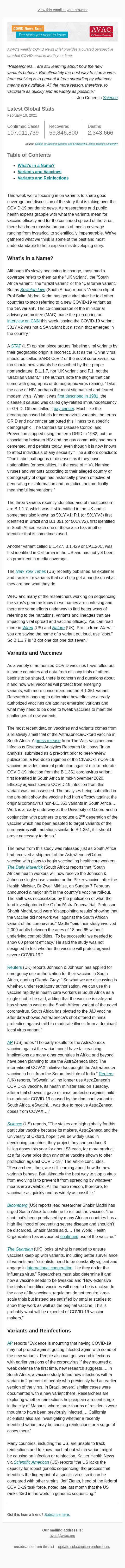

** Latest Global Stats

------------------------------------------------------------

February 10, 2021

Confirmed Cases

107,011,739 Recovered

59,846,800 Deaths

2,343,666

Source: Center for Systems Science and Engineering, Johns Hopkins University ([link removed])

** Table of Contents

------------------------------------------------------------

* What’s in a Name? (#whats)

* Variants and Vaccines (#variants)

* Variants and Reinfections (#reinfect)

This week we’re focusing in on variants to share good coverage and discussion of the story that is taking over the COVID-19 pandemic news. As researchers and public health experts grapple with what the variants mean for vaccine efficacy and for the continued spread of the virus, there has been massive amounts of media coverage ranging from hysterical to scientifically impenetrable. We’ve gathered what we think is some of the best and most understandable to help explain this developing story.

** What’s in a Name?

------------------------------------------------------------

Although it’s slowly beginning to change, most media coverage refers to them as the “UK variant”, the “South Africa variant,” the “Brazil variant” or the “California variant.” But as Sowetan Live ([link removed]) (South Africa) reports “A video clip of Prof Salim Abdool Karim has gone viral after he told other countries to stop referring to a new COVID-19 variant as the ‘SA variant’. The co-chairperson of the ministerial advisory committee (MAC) made the plea during an interview on CNN ([link removed]) this week, saying the

COVID-19 variant 501Y.V2 was not a SA variant but a strain that emerged in the country.”

A STAT ([link removed]) (US) opinion piece argues “labeling viral variants by their geographic origin is incorrect. Just as the ‘China virus’ should be called SARS-CoV-2 or the novel coronavirus, so too should new variants be described by their proper nomenclature: B.1.1.7, not ‘UK variant’ and P.1, not the ‘Brazilian variant.’” The authors note the stigma that can come with geographic or demographic virus naming. “Take the case of HIV, perhaps the most stigmatized and feared modern virus. When it was first described in 1981 ([link removed]) , the disease it caused was called gay-related immunodeficiency, or GRID. Others called it gay cancer ([link removed]) . Much like the geography-based labels for coronavirus variants, the terms GRID and gay cancer attributed this illness to a specific demographic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

stopped using the term GRID in 1982, but the association between HIV and the gay community had been cemented, and persists today, even though it is now known to affect individuals of any sexuality.” The authors conclude: “Don’t label pathogens or diseases as if they have nationalities (or sexualities, in the case of HIV). Naming viruses and variants according to their alleged country or demography of origin has historically proven effective at generating misinformation and prejudice, not medically meaningful interventions.”

The three variants recently identified and of most concern are B.1.1.7, which was first identified in the UK and is sometimes also known as 501Y.V1; P.1 (or 501Y.V3) first identified in Brazil and B.1.351 (or 501Y.V2), first identified in South Africa. Each one of these also has another identifier that is sometimes used.

Another variant called B.1.427, B.1.429 or CAL.20C, was first identified in California in the US and has not yet been as prominent in media coverage.

The New York Times ([link removed]) (US) recently published an explainer and tracker for variants that can help get a handle on what they are and what they do.

WHO and many of the researchers working on sequencing the virus’s genome know these names are confusing and there are some efforts underway to find better ways of referring to the mutations, variants and lineages that are impacting viral spread and vaccine efficacy. You can read more in Wired ([link removed]) (US) and Nature ([link removed]) (UK). Pro tip from Wired: if you are saying the name of a variant out loud, use “dots.” So B.1.1.7 is “B dot one dot one dot seven.”

** Variants and Vaccines

------------------------------------------------------------

As a variety of authorized COVID vaccines have rolled out in some countries and data from efficacy trials of others begins to be shared, there is concern and questions about if and how well vaccines will protect from emerging variants, with more concern around the B.1.351 variant. Research is ongoing to determine how effective already authorized vaccines are against emerging variants and what may need to be done to tweak vaccines to meet the challenges of new variants.

The most recent data on vaccines and variants comes from a relatively small trial of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine in South Africa. A press release ([link removed]) from The Wits Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit says “In an analysis, submitted as a pre-print prior to peer-review publication, a two-dose regimen of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine provides minimal protection against mild-moderate COVID-19 infection from the B.1.351 coronavirus variant first identified in South Africa in mid-November 2020. Efficacy against severe COVID-19 infection from this variant was not assessed. The analyses being submitted in the pre-print show the vaccine had high efficacy against the original coronavirus non-B.1.351 variants in South Africa…. Work is already underway at the University of Oxford and in conjunction with partners to produce a 2^nd generation of the vaccine which has been adapted to target

variants of the coronavirus with mutations similar to B.1.351, if it should prove necessary to do so.”

The news from this study was released just as South Africa had received a shipment of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine with plans to begin vaccinating healthcare workers. The Daily Maverick ([link removed]) (South Africa) reports that “South African health workers will now receive the Johnson & Johnson single dose vaccine or the Pfizer vaccine, after the Health Minister, Dr Zweli Mkhize, on Sunday 7 February announced a major shift in the country’s vaccine roll-out. The shift was necessitated by the publication of what the lead investigator in the Oxford/AstraZeneca trial, Professor Shabir Madhi, said were ‘disappointing results’ showing that the vaccine did not work well against the South African variant of the coronavirus.” Madhi “said their study involved 2,000 adults between the ages of 18 and 65 without underlying comorbidities. ‘To be successful we needed to show 60 percent efficacy.’ He said

the study was not designed to test whether the vaccine will protect against severe COVID-19.”

Reuters ([link removed]) (UK) reports Johnson & Johnson has applied for emergency use authorization for their vaccine in South Africa, quoting Glenda Gray: “’So what we are discussing is whether, under regulatory authorisation, we can use this vaccine rapidly in health care workers in South Africa as a single shot,’ she said, adding that the vaccine is safe and has shown to work on the South African variant of the novel coronavirus. South Africa has pivoted to the J&J vaccine after data showed AstraZeneca’s shot offered minimal protection against mild-to-moderate illness from a dominant local virus variant."

AP ([link removed]) (US) notes “The early results for the AstraZeneca vaccine against the variant could have far-reaching implications as many other countries in Africa and beyond have been planning to use the AstraZeneca shot. The international COVAX initiative has bought the AstraZeneca vaccine in bulk from the Serum Institute of India.” Reuters ([link removed]) (UK) reports, “eSwatini will no longer use AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine, its health minister said on Tuesday, after a trial showed it gave minimal protection against mild-to-moderate COVID-19 caused by the dominant variant in South Africa. eSwatini… was due to receive AstraZeneca doses from COVAX….”

Science ([link removed]) (US) reports, “The stakes are high globally for this particular vaccine because its makers, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, hope it will be widely used in developing countries; they project they can produce 3 billion doses this year for about $3 each, far more product at a far lower price than any other vaccine shown to offer protection against COVID-19.” The article concludes, “Researchers, then, are still learning about how the new variants behave. But ultimately the best way to stop a virus from evolving is to prevent it from spreading by whatever means are available. All the more reason, therefore, to vaccinate as quickly and as widely as possible.”

Bloomberg ([link removed]) (US) reports lead researcher Shabir Madhi has urged South Africa to continue to roll out the vaccine: “the shot that’s been purchased by many African countries has a high likelihood of preventing severe disease and shouldn’t be discarded, Shabir Madhi said…. The World Health Organization has advocated continued ([link removed]) use of the vaccine.”

The Guardian ([link removed]) (UK) looks at what is needed to ensure vaccines keep up with variants, including better surveillance of variants and “scientists need to be constantly vigilant and engage in international cooperation ([link removed]) , like they do for the influenza virus.” Researchers must also determine if and how a vaccine needs to be tweaked and “How extensive the trials of modified vaccines will need to be is unclear. In the case of flu vaccines, regulators do not require large-scale trials but instead are satisfied by smaller studies to show they work as well as the original vaccine. This is probably what will be expected of COVID-19 vaccine makers.”

** Variants and Reinfections

------------------------------------------------------------

AP ([link removed]) reports “Evidence is mounting that having COVID-19 may not protect against getting infected again with some of the new variants. People also can get second infections with earlier versions of the coronavirus if they mounted a weak defense the first time, new research suggests…. In South Africa, a vaccine study found new infections with a variant in 2 percent of people who previously had an earlier version of the virus. In Brazil, several similar cases were documented with a new variant there. Researchers are exploring whether reinfections help explain a recent surge in the city of Manaus, where three-fourths of residents were thought to have been previously infected…. California scientists also are investigating whether a recently identified variant may be causing reinfections or a surge of cases there.”

Many countries, including the US, are unable to track reinfections and to know much about which variant might be causing an infection or reinfection. Kaiser Health News via Scientific American ([link removed]) (US) reports “the US lacks the capacity for robust genetic sequencing, the process that identifies the fingerprint of a specific virus so it can be compared with other strains. Jeff Zients, head of the federal COVID-19 task force, noted late last month that the US ranks 43rd in the world in genomic sequencing.”

Got this from a friend? Subscribe here. ([link removed])

============================================================

Our mailing address is:

** [email protected] (mailto:[email protected])

** unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

** update subscription preferences ([link removed])

AVAC's weekly COVID News Brief provides a curated perspective on what COVID news is worth your time.

"Researchers... are still learning about how the new variants behave. But ultimately the best way to stop a virus from evolving is to prevent it from spreading by whatever means are available. All the more reason, therefore, to vaccinate as quickly and as widely as possible.”

— Jon Cohen in Science ([link removed])

** Latest Global Stats

------------------------------------------------------------

February 10, 2021

Confirmed Cases

107,011,739 Recovered

59,846,800 Deaths

2,343,666

Source: Center for Systems Science and Engineering, Johns Hopkins University ([link removed])

** Table of Contents

------------------------------------------------------------

* What’s in a Name? (#whats)

* Variants and Vaccines (#variants)

* Variants and Reinfections (#reinfect)

This week we’re focusing in on variants to share good coverage and discussion of the story that is taking over the COVID-19 pandemic news. As researchers and public health experts grapple with what the variants mean for vaccine efficacy and for the continued spread of the virus, there has been massive amounts of media coverage ranging from hysterical to scientifically impenetrable. We’ve gathered what we think is some of the best and most understandable to help explain this developing story.

** What’s in a Name?

------------------------------------------------------------

Although it’s slowly beginning to change, most media coverage refers to them as the “UK variant”, the “South Africa variant,” the “Brazil variant” or the “California variant.” But as Sowetan Live ([link removed]) (South Africa) reports “A video clip of Prof Salim Abdool Karim has gone viral after he told other countries to stop referring to a new COVID-19 variant as the ‘SA variant’. The co-chairperson of the ministerial advisory committee (MAC) made the plea during an interview on CNN ([link removed]) this week, saying the

COVID-19 variant 501Y.V2 was not a SA variant but a strain that emerged in the country.”

A STAT ([link removed]) (US) opinion piece argues “labeling viral variants by their geographic origin is incorrect. Just as the ‘China virus’ should be called SARS-CoV-2 or the novel coronavirus, so too should new variants be described by their proper nomenclature: B.1.1.7, not ‘UK variant’ and P.1, not the ‘Brazilian variant.’” The authors note the stigma that can come with geographic or demographic virus naming. “Take the case of HIV, perhaps the most stigmatized and feared modern virus. When it was first described in 1981 ([link removed]) , the disease it caused was called gay-related immunodeficiency, or GRID. Others called it gay cancer ([link removed]) . Much like the geography-based labels for coronavirus variants, the terms GRID and gay cancer attributed this illness to a specific demographic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

stopped using the term GRID in 1982, but the association between HIV and the gay community had been cemented, and persists today, even though it is now known to affect individuals of any sexuality.” The authors conclude: “Don’t label pathogens or diseases as if they have nationalities (or sexualities, in the case of HIV). Naming viruses and variants according to their alleged country or demography of origin has historically proven effective at generating misinformation and prejudice, not medically meaningful interventions.”

The three variants recently identified and of most concern are B.1.1.7, which was first identified in the UK and is sometimes also known as 501Y.V1; P.1 (or 501Y.V3) first identified in Brazil and B.1.351 (or 501Y.V2), first identified in South Africa. Each one of these also has another identifier that is sometimes used.

Another variant called B.1.427, B.1.429 or CAL.20C, was first identified in California in the US and has not yet been as prominent in media coverage.

The New York Times ([link removed]) (US) recently published an explainer and tracker for variants that can help get a handle on what they are and what they do.

WHO and many of the researchers working on sequencing the virus’s genome know these names are confusing and there are some efforts underway to find better ways of referring to the mutations, variants and lineages that are impacting viral spread and vaccine efficacy. You can read more in Wired ([link removed]) (US) and Nature ([link removed]) (UK). Pro tip from Wired: if you are saying the name of a variant out loud, use “dots.” So B.1.1.7 is “B dot one dot one dot seven.”

** Variants and Vaccines

------------------------------------------------------------

As a variety of authorized COVID vaccines have rolled out in some countries and data from efficacy trials of others begins to be shared, there is concern and questions about if and how well vaccines will protect from emerging variants, with more concern around the B.1.351 variant. Research is ongoing to determine how effective already authorized vaccines are against emerging variants and what may need to be done to tweak vaccines to meet the challenges of new variants.

The most recent data on vaccines and variants comes from a relatively small trial of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine in South Africa. A press release ([link removed]) from The Wits Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit says “In an analysis, submitted as a pre-print prior to peer-review publication, a two-dose regimen of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine provides minimal protection against mild-moderate COVID-19 infection from the B.1.351 coronavirus variant first identified in South Africa in mid-November 2020. Efficacy against severe COVID-19 infection from this variant was not assessed. The analyses being submitted in the pre-print show the vaccine had high efficacy against the original coronavirus non-B.1.351 variants in South Africa…. Work is already underway at the University of Oxford and in conjunction with partners to produce a 2^nd generation of the vaccine which has been adapted to target

variants of the coronavirus with mutations similar to B.1.351, if it should prove necessary to do so.”

The news from this study was released just as South Africa had received a shipment of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine with plans to begin vaccinating healthcare workers. The Daily Maverick ([link removed]) (South Africa) reports that “South African health workers will now receive the Johnson & Johnson single dose vaccine or the Pfizer vaccine, after the Health Minister, Dr Zweli Mkhize, on Sunday 7 February announced a major shift in the country’s vaccine roll-out. The shift was necessitated by the publication of what the lead investigator in the Oxford/AstraZeneca trial, Professor Shabir Madhi, said were ‘disappointing results’ showing that the vaccine did not work well against the South African variant of the coronavirus.” Madhi “said their study involved 2,000 adults between the ages of 18 and 65 without underlying comorbidities. ‘To be successful we needed to show 60 percent efficacy.’ He said

the study was not designed to test whether the vaccine will protect against severe COVID-19.”

Reuters ([link removed]) (UK) reports Johnson & Johnson has applied for emergency use authorization for their vaccine in South Africa, quoting Glenda Gray: “’So what we are discussing is whether, under regulatory authorisation, we can use this vaccine rapidly in health care workers in South Africa as a single shot,’ she said, adding that the vaccine is safe and has shown to work on the South African variant of the novel coronavirus. South Africa has pivoted to the J&J vaccine after data showed AstraZeneca’s shot offered minimal protection against mild-to-moderate illness from a dominant local virus variant."

AP ([link removed]) (US) notes “The early results for the AstraZeneca vaccine against the variant could have far-reaching implications as many other countries in Africa and beyond have been planning to use the AstraZeneca shot. The international COVAX initiative has bought the AstraZeneca vaccine in bulk from the Serum Institute of India.” Reuters ([link removed]) (UK) reports, “eSwatini will no longer use AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine, its health minister said on Tuesday, after a trial showed it gave minimal protection against mild-to-moderate COVID-19 caused by the dominant variant in South Africa. eSwatini… was due to receive AstraZeneca doses from COVAX….”

Science ([link removed]) (US) reports, “The stakes are high globally for this particular vaccine because its makers, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, hope it will be widely used in developing countries; they project they can produce 3 billion doses this year for about $3 each, far more product at a far lower price than any other vaccine shown to offer protection against COVID-19.” The article concludes, “Researchers, then, are still learning about how the new variants behave. But ultimately the best way to stop a virus from evolving is to prevent it from spreading by whatever means are available. All the more reason, therefore, to vaccinate as quickly and as widely as possible.”

Bloomberg ([link removed]) (US) reports lead researcher Shabir Madhi has urged South Africa to continue to roll out the vaccine: “the shot that’s been purchased by many African countries has a high likelihood of preventing severe disease and shouldn’t be discarded, Shabir Madhi said…. The World Health Organization has advocated continued ([link removed]) use of the vaccine.”

The Guardian ([link removed]) (UK) looks at what is needed to ensure vaccines keep up with variants, including better surveillance of variants and “scientists need to be constantly vigilant and engage in international cooperation ([link removed]) , like they do for the influenza virus.” Researchers must also determine if and how a vaccine needs to be tweaked and “How extensive the trials of modified vaccines will need to be is unclear. In the case of flu vaccines, regulators do not require large-scale trials but instead are satisfied by smaller studies to show they work as well as the original vaccine. This is probably what will be expected of COVID-19 vaccine makers.”

** Variants and Reinfections

------------------------------------------------------------

AP ([link removed]) reports “Evidence is mounting that having COVID-19 may not protect against getting infected again with some of the new variants. People also can get second infections with earlier versions of the coronavirus if they mounted a weak defense the first time, new research suggests…. In South Africa, a vaccine study found new infections with a variant in 2 percent of people who previously had an earlier version of the virus. In Brazil, several similar cases were documented with a new variant there. Researchers are exploring whether reinfections help explain a recent surge in the city of Manaus, where three-fourths of residents were thought to have been previously infected…. California scientists also are investigating whether a recently identified variant may be causing reinfections or a surge of cases there.”

Many countries, including the US, are unable to track reinfections and to know much about which variant might be causing an infection or reinfection. Kaiser Health News via Scientific American ([link removed]) (US) reports “the US lacks the capacity for robust genetic sequencing, the process that identifies the fingerprint of a specific virus so it can be compared with other strains. Jeff Zients, head of the federal COVID-19 task force, noted late last month that the US ranks 43rd in the world in genomic sequencing.”

Got this from a friend? Subscribe here. ([link removed])

============================================================

Our mailing address is:

** [email protected] (mailto:[email protected])

** unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

** update subscription preferences ([link removed])

Message Analysis

- Sender: AVAC: Global Advocacy for HIV Prevention

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- MailChimp