| From | Peter Wagner <[email protected]> |

| Subject | New data clarifies the link between homelessness and incarceration |

| Date | February 10, 2021 5:08 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Plus: Formerly incarcerated people, their families face food insecurity

Prison Policy Initiative updates for February 10, 2021 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New data: The revolving door between homeless shelters and prisons in Connecticut [[link removed]] New statewide data from the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness underscore the harms of criminalizing homelessness and the destabilizing effects of incarceration. [[link removed]]

by Alexi Jones

In December, officials in Seattle drew the ire of activists when they decided to sweep a homeless encampment in Cal Anderson park despite warnings from public health officials. Dozens of people experiencing homelessness were displaced and 24 people were arrested just a week before Christmas.

Seattle is not alone. At the same time that cities around the country, including Denver [[link removed]] and Reno [[link removed]], continue police sweeps of homeless encampments during the pandemic, researchers in Connecticut have compiled recent data [[link removed]] showing that this criminalization of homelessness - together with barriers to housing upon re-entry - has created a revolving door between prisons and homeless shelters.

Research has consistently shown a strong link between incarceration and homelessness. Our 2018 report [[link removed]] found that formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. Other national data [[link removed]] shows 50,000 people enter shelters directly from correctional facilities per year.1 And homelessness is a major [[link removed]] predictor [[link removed]] of involvement with the juvenile justice system, which means that for many youth, the cycle of incarceration and homelessness starts early.

To date, there has been no national data on how many people experiencing homelessness have had prior criminal justice involvement. New data from the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness [[link removed]] helps fill this gap. The study was also able to parse how many people experienced homelessness before incarceration versus how many experienced homelessness after release - underscoring both the harms of criminalizing homelessness and the destabilizing effects of incarceration. Above all, the findings illustrate the importance of including stable housing in states’ public safety agendas.

The study’s main findings

The Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness (CCEH) matched data from the 450,000 people who have been admitted to the Connecticut Department of Corrections (DOC), the state's joint prison and jail system, and the 17,226 people who used a shelter in their network between Jan. 2016 and Jan. 2019, finding that half of the people (8,187) who used homeless shelters were formerly incarcerated. Moreover, they found that 1 in 5 people who used homeless shelters had been released from prison in the past three years. The CCEH network includes 88% of all emergency shelters in the state.

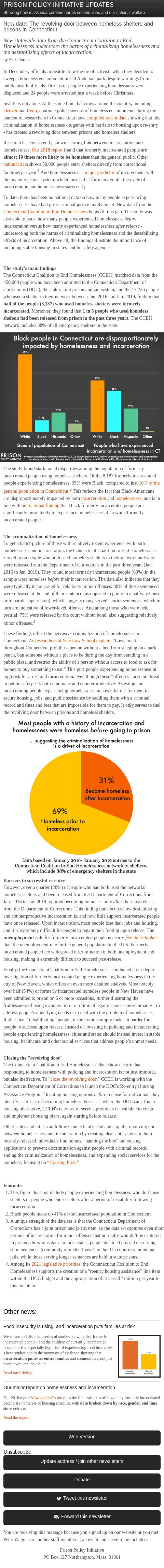

The study found stark racial disparities among the population of formerly incarcerated people using homeless shelters. Of the 8,187 formerly incarcerated people experiencing homelessness, 35% were Black, compared to just 10% of the general population in Connecticut [[link removed]].2 This reflects the fact that Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by both incarceration [[link removed]] and homelessness [[link removed]], and is in line with our national finding [[link removed]] that Black formerly incarcerated people are significantly more likely to experience homelessness than white formerly incarcerated people.

The criminalization of homelessness

To get a better picture of those with relatively recent experience with both homelessness and incarceration, the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness zeroed in on people who both used homeless shelters in their network and who were released from the Department of Corrections in the past three years (Jan. 2016 to Jan. 2019). They found most formerly incarcerated people (69%) in the sample were homeless before their incarceration. The data also indicates that they were typically incarcerated for relatively minor offenses: 80% of those sentenced were released at the end of their sentence (as opposed to going to a halfway house or to parole supervision), which suggests many served shorter sentences, which in turn are indicative of lower-level offenses. And among those who were held pretrial, 75% were released by the court without bond, also suggesting relatively minor offenses.3

These findings reflect the pervasive criminalization of homelessness in Connecticut. As researchers at Yale Law School explain [[link removed]], “Laws in cities throughout Connecticut prohibit a person without a bed from sleeping on a park bench, ban someone without a place to be during the day from standing in a public plaza, and restrict the ability of a person without access to food to ask for money to buy something to eat.” This puts people experiencing homelessness at high risk for arrest and incarceration, even though these “offenses” pose no threat to public safety. It’s both inhumane and counterproductive: Arresting and incarcerating people experiencing homelessness makes it harder for them to secure housing, jobs, and public assistance by saddling them with a criminal record and fines and fees that are impossible for them to pay. It only serves to fuel the revolving door between prisons and homeless shelters.

Barriers to successful re-entry

However, over a quarter (28%) of people who had both used the networks’ homeless shelters and been released from the Department of Corrections from Jan. 2016 to Jan. 2019 reported becoming homeless only after their last release from the Department of Corrections. This finding underscores how destabilizing and counterproductive incarceration is, and how little support incarcerated people have once released. Upon incarceration, most people lose their jobs and housing, and it is extremely difficult for people to regain their footing upon release. The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is nearly five times higher [[link removed]]than the unemployment rate for the general population in the U.S. Formerly incarcerated people face widespread discrimination in both unemployment and housing, making it extremely difficult to succeed post-release.

Finally, the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness conducted an in-depth investigation of formerly incarcerated people experiencing homelessness in the city of New Haven, which offers an even more detailed analysis. Most notably, over half (54%) of formerly incarcerated homeless people in New Haven have been admitted to prison on 6 or more occasions, further illustrating the fruitlessness of using incarceration - or criminal legal responses more broadly - to address people’s underlying needs or to deal with the problem of homelessness. Rather than “rehabilitating” people, incarceration simply makes it harder for people to succeed upon release. Instead of investing in policing and incarcerating people experiencing homelessness, cities and states should instead invest in stable housing, healthcare, and other social services that address people’s unmet needs.

Closing the "revolving door"

The Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness’ data show clearly that responding to homelessness with policing and incarceration is not just immoral, but also ineffective. To " close the revolving door [[link removed]]," CCEH is working with the Connecticut Department of Corrections to launch the DOC's Re-entry Housing Assistance Program, 4 locating housing options before release for individuals they identify as at-risk of becoming homeless. For cases where the DOC can't find a housing alternative, CCEH's network of service providers is available to create and implement housing plans, again starting before release.

Other states and cities can follow Connecticut's lead and stop the revolving door between homelessness and incarceration by creating clear-cut systems to help recently-released individuals find homes, "banning the box" on housing applications to prevent discrimination against people with criminal records, ending the criminalization of homelessness, and expanding social services for the homeless, focusing on “ Housing First [[link removed]].”

Footnotes This figure does not include people experiencing homelessness who don’t use shelters or people who enter shelters after a period of instability following incarceration. Black people make up 41% of the incarcerated population in Connecticut. A unique strength of the data set is that the Connecticut Department of Corrections has a joint prison and jail system, so the data set captures even short periods of incarceration for minor offenses that normally wouldn’t be captured in prison admissions data. In most states, people detained pretrial or serving short sentences (commonly of under 1 year) are held in county or municipal jails, while those serving longer sentences are held in state prisons. Among its 2021 legislative priorities [[link removed]], the Connnecticut Coalition to End Homelessness supports the creation of a "reentry housing assistance" line item within the DOC budget and the appropriation of at least $2 million per year to this line item. Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Food insecurity is rising, and incarceration puts families at risk [[link removed]]

We curate and discuss a series of studies showing that formerly incarcerated people - and the children of currently incarcerated people - are at especially high risk of experiencing food insecurity. These studies add to the mountain of evidence showing that incarceration punishes entire families and communities, not just people who are locked up.

Read our briefing. [[link removed]]

Our major report on homelessness and incarceration [[link removed]]

Our 2018 report Nowhere to Go [[link removed]] provides the first estimates of how many formerly incarcerated people are homeless or housing insecure, with data broken down by race, gender, and time since release.

Read the report. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for February 10, 2021 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New data: The revolving door between homeless shelters and prisons in Connecticut [[link removed]] New statewide data from the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness underscore the harms of criminalizing homelessness and the destabilizing effects of incarceration. [[link removed]]

by Alexi Jones

In December, officials in Seattle drew the ire of activists when they decided to sweep a homeless encampment in Cal Anderson park despite warnings from public health officials. Dozens of people experiencing homelessness were displaced and 24 people were arrested just a week before Christmas.

Seattle is not alone. At the same time that cities around the country, including Denver [[link removed]] and Reno [[link removed]], continue police sweeps of homeless encampments during the pandemic, researchers in Connecticut have compiled recent data [[link removed]] showing that this criminalization of homelessness - together with barriers to housing upon re-entry - has created a revolving door between prisons and homeless shelters.

Research has consistently shown a strong link between incarceration and homelessness. Our 2018 report [[link removed]] found that formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. Other national data [[link removed]] shows 50,000 people enter shelters directly from correctional facilities per year.1 And homelessness is a major [[link removed]] predictor [[link removed]] of involvement with the juvenile justice system, which means that for many youth, the cycle of incarceration and homelessness starts early.

To date, there has been no national data on how many people experiencing homelessness have had prior criminal justice involvement. New data from the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness [[link removed]] helps fill this gap. The study was also able to parse how many people experienced homelessness before incarceration versus how many experienced homelessness after release - underscoring both the harms of criminalizing homelessness and the destabilizing effects of incarceration. Above all, the findings illustrate the importance of including stable housing in states’ public safety agendas.

The study’s main findings

The Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness (CCEH) matched data from the 450,000 people who have been admitted to the Connecticut Department of Corrections (DOC), the state's joint prison and jail system, and the 17,226 people who used a shelter in their network between Jan. 2016 and Jan. 2019, finding that half of the people (8,187) who used homeless shelters were formerly incarcerated. Moreover, they found that 1 in 5 people who used homeless shelters had been released from prison in the past three years. The CCEH network includes 88% of all emergency shelters in the state.

The study found stark racial disparities among the population of formerly incarcerated people using homeless shelters. Of the 8,187 formerly incarcerated people experiencing homelessness, 35% were Black, compared to just 10% of the general population in Connecticut [[link removed]].2 This reflects the fact that Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by both incarceration [[link removed]] and homelessness [[link removed]], and is in line with our national finding [[link removed]] that Black formerly incarcerated people are significantly more likely to experience homelessness than white formerly incarcerated people.

The criminalization of homelessness

To get a better picture of those with relatively recent experience with both homelessness and incarceration, the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness zeroed in on people who both used homeless shelters in their network and who were released from the Department of Corrections in the past three years (Jan. 2016 to Jan. 2019). They found most formerly incarcerated people (69%) in the sample were homeless before their incarceration. The data also indicates that they were typically incarcerated for relatively minor offenses: 80% of those sentenced were released at the end of their sentence (as opposed to going to a halfway house or to parole supervision), which suggests many served shorter sentences, which in turn are indicative of lower-level offenses. And among those who were held pretrial, 75% were released by the court without bond, also suggesting relatively minor offenses.3

These findings reflect the pervasive criminalization of homelessness in Connecticut. As researchers at Yale Law School explain [[link removed]], “Laws in cities throughout Connecticut prohibit a person without a bed from sleeping on a park bench, ban someone without a place to be during the day from standing in a public plaza, and restrict the ability of a person without access to food to ask for money to buy something to eat.” This puts people experiencing homelessness at high risk for arrest and incarceration, even though these “offenses” pose no threat to public safety. It’s both inhumane and counterproductive: Arresting and incarcerating people experiencing homelessness makes it harder for them to secure housing, jobs, and public assistance by saddling them with a criminal record and fines and fees that are impossible for them to pay. It only serves to fuel the revolving door between prisons and homeless shelters.

Barriers to successful re-entry

However, over a quarter (28%) of people who had both used the networks’ homeless shelters and been released from the Department of Corrections from Jan. 2016 to Jan. 2019 reported becoming homeless only after their last release from the Department of Corrections. This finding underscores how destabilizing and counterproductive incarceration is, and how little support incarcerated people have once released. Upon incarceration, most people lose their jobs and housing, and it is extremely difficult for people to regain their footing upon release. The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is nearly five times higher [[link removed]]than the unemployment rate for the general population in the U.S. Formerly incarcerated people face widespread discrimination in both unemployment and housing, making it extremely difficult to succeed post-release.

Finally, the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness conducted an in-depth investigation of formerly incarcerated people experiencing homelessness in the city of New Haven, which offers an even more detailed analysis. Most notably, over half (54%) of formerly incarcerated homeless people in New Haven have been admitted to prison on 6 or more occasions, further illustrating the fruitlessness of using incarceration - or criminal legal responses more broadly - to address people’s underlying needs or to deal with the problem of homelessness. Rather than “rehabilitating” people, incarceration simply makes it harder for people to succeed upon release. Instead of investing in policing and incarcerating people experiencing homelessness, cities and states should instead invest in stable housing, healthcare, and other social services that address people’s unmet needs.

Closing the "revolving door"

The Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness’ data show clearly that responding to homelessness with policing and incarceration is not just immoral, but also ineffective. To " close the revolving door [[link removed]]," CCEH is working with the Connecticut Department of Corrections to launch the DOC's Re-entry Housing Assistance Program, 4 locating housing options before release for individuals they identify as at-risk of becoming homeless. For cases where the DOC can't find a housing alternative, CCEH's network of service providers is available to create and implement housing plans, again starting before release.

Other states and cities can follow Connecticut's lead and stop the revolving door between homelessness and incarceration by creating clear-cut systems to help recently-released individuals find homes, "banning the box" on housing applications to prevent discrimination against people with criminal records, ending the criminalization of homelessness, and expanding social services for the homeless, focusing on “ Housing First [[link removed]].”

Footnotes This figure does not include people experiencing homelessness who don’t use shelters or people who enter shelters after a period of instability following incarceration. Black people make up 41% of the incarcerated population in Connecticut. A unique strength of the data set is that the Connecticut Department of Corrections has a joint prison and jail system, so the data set captures even short periods of incarceration for minor offenses that normally wouldn’t be captured in prison admissions data. In most states, people detained pretrial or serving short sentences (commonly of under 1 year) are held in county or municipal jails, while those serving longer sentences are held in state prisons. Among its 2021 legislative priorities [[link removed]], the Connnecticut Coalition to End Homelessness supports the creation of a "reentry housing assistance" line item within the DOC budget and the appropriation of at least $2 million per year to this line item. Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Food insecurity is rising, and incarceration puts families at risk [[link removed]]

We curate and discuss a series of studies showing that formerly incarcerated people - and the children of currently incarcerated people - are at especially high risk of experiencing food insecurity. These studies add to the mountain of evidence showing that incarceration punishes entire families and communities, not just people who are locked up.

Read our briefing. [[link removed]]

Our major report on homelessness and incarceration [[link removed]]

Our 2018 report Nowhere to Go [[link removed]] provides the first estimates of how many formerly incarcerated people are homeless or housing insecure, with data broken down by race, gender, and time since release.

Read the report. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor