| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | In Brazil’s First Elections Under Bolsonaro, Black Women are Fighting Back |

| Date | November 15, 2020 1:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[Amidst violence and COVID-19 restrictions, Black women in Brazil

are mobilizing to win seats in the November 15th municipal elections

and open the gateway to electoral power. Brazil ranks 132nd out of 192

countries in women’s representation.] [[link removed]]

IN BRAZIL’S FIRST ELECTIONS UNDER BOLSONARO, BLACK WOMEN ARE

FIGHTING BACK

[[link removed]]

Bruna Pereira/ Macarena Aguilar

November 12, 2020

OpenDemocracy

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ Amidst violence and COVID-19 restrictions, Black women in Brazil

are mobilizing to win seats in the November 15th municipal elections

and open the gateway to electoral power. Brazil ranks 132nd out of 192

countries in women’s representation. _

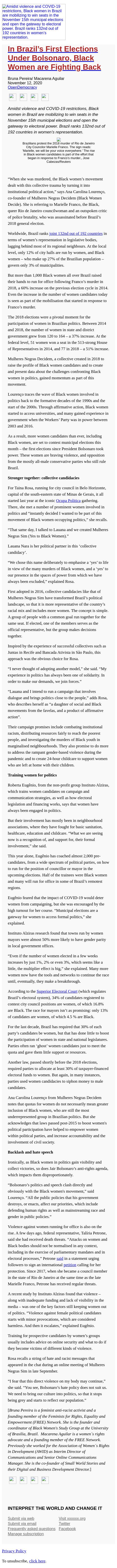

Brazilians protest the 2018 murder of Rio de Janeiro City Councilor

Marielle Franco. The sign reads: 'Marielle, we will be your voice

everywhere.' The rise in Black women candidates is part of the effort

that began in response to Franco’s murder., Jose Cabezas/Reuters

“When she was murdered, the Black women’s movement dealt with this

collective trauma by turning it into institutional political

action,” says Ana Carolina Lourenço, co-founder of Mulheres Negras

Decidem (Black Women Decide). She is referring to Marielle Franco, the

Black, queer Rio de Janeiro councilwoman and an outspoken critic of

police brutality, who was assassinated before Brazil’s 2018 general

election.

Worldwide, Brazil ranks joint 132nd out of 192 countries

[[link removed]] in terms of women’s

representation in legislative bodies, lagging behind most of its

regional neighbours. At the local level, only 12% of city halls are

run by women, and Black women – who make up 27% of the Brazilian

population – govern only 3% of municipalities.

But more than 1,000 Black women all over Brazil raised their hands to

run for office following Franco’s murder in 2018, a 60% increase on

the previous election cycle in 2014. Even the increase in the number

of women candidates today is seen as part of the mobilisation that

started in response to Franco’s murder.

The 2018 elections were a pivotal moment for the participation of

women in Brazilian politics. Between 2014 and 2018, the number of

women in state and district government grew from 120 to 164 – a 37%

increase. At the federal level, 51 women won a seat in the 513-strong

House of Representatives in 2014, and 77 in 2018 – a 51% increase.

Mulheres Negras Decidem_,_ a collective created in 2018 to raise the

profile of Black women candidates and to create and present data about

the challenges confronting Black women in politics, gained momentum as

part of this movement.

Lourenço traces the wave of Black women involved in politics back to

the formative decades of the 1990s and the start of the 2000s. Through

affirmative action, Black women started to access universities, and

many gained experience in government when the Workers’ Party was in

power between 2003 and 2016.

As a result, more women candidates than ever, including Black women,

are set to contest municipal elections this month – the first

elections since President Bolsonaro took power. These women are

braving violence, and opposition from the mostly all-male conservative

parties who still rule Brazil.

STRONGER TOGETHER: COLLECTIVE CANDIDACIES

For Taina Rosa, running for city council in Belo Horizonte, capital of

the south-eastern state of Minas de Gerais, it all started last year

at the iconic Ocupa Politica

[[link removed]] gathering.

There, she met a number of prominent women involved in politics and

“instantly decided I wanted to be part of this movement of Black

women occupying politics,” she recalls.

“That same day, I talked to Lauana and we created Mulheres Negras

Sim (Yes to Black Women).”

Lauana Nara is her political partner in this ‘collective

candidacy’_._

“We chose this name deliberately to emphasise a ‘yes’ to life in

view of the many murders of Black women, and a ‘yes’ to our

presence in the spaces of power from which we have always been

excluded,” explained Rosa.

First adopted in 2016, collective candidacies like that of Mulheres

Negras Sim have transformed Brazil’s political landscape, so that it

is more representative of the country’s racial mix and includes more

women. The concept is simple. A group of people with a common goal run

together for the same seat. If elected, one of the members serves as

the official representative, but the group makes decisions together.

Inspired by the experience of successful collectives such as Juntas in

Recife and Bancada Ativista in São Paulo, this approach was the

obvious choice for Rosa.

“I never thought of adopting another model,” she said. “My

experience in politics has always been one of solidarity. In order to

make our demands, we join forces.”

“Lauana and I intend to run a campaign that involves dialogue and

brings politics close to the people,” adds Rosa, who describes

herself as “a daughter of social and Black movements from the

favelas, and a product of affirmative action”.

Their campaign promises include combating institutional racism,

distributing resources fairly to reach the poorest people, and

investigating the murders of Black youth in marginalised

neighbourhoods. They also promise to do more to address the rampant

gender-based violence during the pandemic and to create 24-hour

childcare to support women who are left at home with their children.

TRAINING WOMEN FOR POLITICS

Roberta Eugênio, from the non-profit group Instituto Alziras, which

trains women candidates on campaign and communication strategies, as

well as how electoral legislation and financing works, says that women

have always been engaged in politics.

But their involvement has mostly been in neighbourhood associations,

where they have fought for basic sanitation, healthcare, education and

childcare. “What we are seeing now is a recognition of, and support

for, their formal involvement,” she said.

This year alone, Eugênio has coached almost 2,000 pre-candidates,

from a wide spectrum of political parties, on how to run for the

position of councillor or mayor in the upcoming elections. Half of the

trainees were Black women and many will run for office in some of

Brazil’s remotest regions.

Eugênio feared that the impact of COVID-19 would deter women from

campaigning, but she was encouraged by the high turnout for her

course. “Municipal elections are a gateway for women to access

formal politics,” she explained.

Instituto Alziras research found that towns run by women mayors were

almost 50% more likely to have gender parity in local government

offices.

“Even if the number of women elected in a few weeks increases by

just 1%, 2% or even 3%, which seems like a little, the multiplier

effect is big,” she explained. Many more women now have the tools

and networks to continue the race until, eventually, they make a

breakthrough.

According to the Superior Electoral Court

[[link removed]] (which regulates Brazil’s electoral

system), [[link removed]] 34% of candidates registered to

contest city council positions are women, of which 16.8% are Black.

The race for mayors isn’t as promising: only 13% of candidates are

women, of which 4.5 % are Black.

For the last decade, Brazil has required that 30% of each party’s

candidates be women, but that has done little to boost the

participation of women in state and national legislatures. Parties

often ran ‘ghost’ women candidates just to meet the quota and gave

them little support or resources.

Another law, passed shortly before the 2018 elections, required

parties to allocate at least 30% of taxpayer-financed electoral funds

to women. But again, in many instances, parties used women candidacies

to siphon money to male candidates.

Ana Carolina Lourenço from Mulheres Negras Decidem notes that quotas

for women do not necessarily mean greater inclusion of Black women,

who are still the most underrepresented group in Brazilian politics.

But she acknowledges that laws passed post-2015 to boost women's

political participation have helped to empower women within political

parties, and increase accountability and the involvement of civil

society.

BACKLASH AND HATE SPEECH

Ironically, as Black women in politics gain visibility and collect

victories, so does Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-rights agenda, which

impacts them disproportionately.

“Bolsonaro’s politics and speech clash directly and obviously with

the Black women's movement,” said Lourenço. “All the public

policies that his government destroys, or enacts, affect our

priorities, which include defending human rights as well as

mainstreaming race and gender in public policies.”

Violence against women running for office is also on the rise. A few

days ago, federal representative, Talíria Petrone, said she had

received death threats. “Attacks on women and Black bodies should

not be normalised in any context, including in the exercise of

parliamentary mandates and in electoral processes,” Petrone said

[[link removed]] in

a statement urging followers to sign an international petition

[[link removed]] calling

for her protection. Since 2017, when she became a council member in

the state of Rio de Janeiro at the same time as the late Marielle

Franco, Petrone has received regular threats.

A recent study by Instituto Alziras found that violence – along with

inadequate funding and lack of visibility in the media – was one of

the key factors still keeping women out of politics. “Violence

against female political candidates starts with minor provocations,

which are considered harmless. And then it escalates,” explained

Eugênio.

Training for prospective candidates by women’s groups usually

includes advice on online security and what to do if they become

victims of different kinds of violence.

Rosa recalls a string of hate and racist messages that appeared in the

chat during an online meeting of Mulheres Negras Sim in late

September.

“I fear that this direct violence on my body may continue,” she

said. “You see, Bolsonaro’s hate policy does not suit us. We need

to bring our culture into politics, so that it stops being grey and

starts to reflect our population.”

[_Bruna Pereira is a feminist anti-racist activist and a founding

member of the Feminists for Rights, Equality and Empowerment (FREE)

Network. She is the founder and coordinator of Black Women's Study

Group at the University of Brasilia, Brazil. Macarena Aguilar is a

women´s rights advocate and a founding member of the FREE Network.

Previously she worked for the Association of Women´s Rights in

Development (AWID) as Interim Director of Communications and Senior

Online Communications Manager. She is the co-founder of Small World

Stories and their Digital and Business Development Director._]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

are mobilizing to win seats in the November 15th municipal elections

and open the gateway to electoral power. Brazil ranks 132nd out of 192

countries in women’s representation.] [[link removed]]

IN BRAZIL’S FIRST ELECTIONS UNDER BOLSONARO, BLACK WOMEN ARE

FIGHTING BACK

[[link removed]]

Bruna Pereira/ Macarena Aguilar

November 12, 2020

OpenDemocracy

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ Amidst violence and COVID-19 restrictions, Black women in Brazil

are mobilizing to win seats in the November 15th municipal elections

and open the gateway to electoral power. Brazil ranks 132nd out of 192

countries in women’s representation. _

Brazilians protest the 2018 murder of Rio de Janeiro City Councilor

Marielle Franco. The sign reads: 'Marielle, we will be your voice

everywhere.' The rise in Black women candidates is part of the effort

that began in response to Franco’s murder., Jose Cabezas/Reuters

“When she was murdered, the Black women’s movement dealt with this

collective trauma by turning it into institutional political

action,” says Ana Carolina Lourenço, co-founder of Mulheres Negras

Decidem (Black Women Decide). She is referring to Marielle Franco, the

Black, queer Rio de Janeiro councilwoman and an outspoken critic of

police brutality, who was assassinated before Brazil’s 2018 general

election.

Worldwide, Brazil ranks joint 132nd out of 192 countries

[[link removed]] in terms of women’s

representation in legislative bodies, lagging behind most of its

regional neighbours. At the local level, only 12% of city halls are

run by women, and Black women – who make up 27% of the Brazilian

population – govern only 3% of municipalities.

But more than 1,000 Black women all over Brazil raised their hands to

run for office following Franco’s murder in 2018, a 60% increase on

the previous election cycle in 2014. Even the increase in the number

of women candidates today is seen as part of the mobilisation that

started in response to Franco’s murder.

The 2018 elections were a pivotal moment for the participation of

women in Brazilian politics. Between 2014 and 2018, the number of

women in state and district government grew from 120 to 164 – a 37%

increase. At the federal level, 51 women won a seat in the 513-strong

House of Representatives in 2014, and 77 in 2018 – a 51% increase.

Mulheres Negras Decidem_,_ a collective created in 2018 to raise the

profile of Black women candidates and to create and present data about

the challenges confronting Black women in politics, gained momentum as

part of this movement.

Lourenço traces the wave of Black women involved in politics back to

the formative decades of the 1990s and the start of the 2000s. Through

affirmative action, Black women started to access universities, and

many gained experience in government when the Workers’ Party was in

power between 2003 and 2016.

As a result, more women candidates than ever, including Black women,

are set to contest municipal elections this month – the first

elections since President Bolsonaro took power. These women are

braving violence, and opposition from the mostly all-male conservative

parties who still rule Brazil.

STRONGER TOGETHER: COLLECTIVE CANDIDACIES

For Taina Rosa, running for city council in Belo Horizonte, capital of

the south-eastern state of Minas de Gerais, it all started last year

at the iconic Ocupa Politica

[[link removed]] gathering.

There, she met a number of prominent women involved in politics and

“instantly decided I wanted to be part of this movement of Black

women occupying politics,” she recalls.

“That same day, I talked to Lauana and we created Mulheres Negras

Sim (Yes to Black Women).”

Lauana Nara is her political partner in this ‘collective

candidacy’_._

“We chose this name deliberately to emphasise a ‘yes’ to life in

view of the many murders of Black women, and a ‘yes’ to our

presence in the spaces of power from which we have always been

excluded,” explained Rosa.

First adopted in 2016, collective candidacies like that of Mulheres

Negras Sim have transformed Brazil’s political landscape, so that it

is more representative of the country’s racial mix and includes more

women. The concept is simple. A group of people with a common goal run

together for the same seat. If elected, one of the members serves as

the official representative, but the group makes decisions together.

Inspired by the experience of successful collectives such as Juntas in

Recife and Bancada Ativista in São Paulo, this approach was the

obvious choice for Rosa.

“I never thought of adopting another model,” she said. “My

experience in politics has always been one of solidarity. In order to

make our demands, we join forces.”

“Lauana and I intend to run a campaign that involves dialogue and

brings politics close to the people,” adds Rosa, who describes

herself as “a daughter of social and Black movements from the

favelas, and a product of affirmative action”.

Their campaign promises include combating institutional racism,

distributing resources fairly to reach the poorest people, and

investigating the murders of Black youth in marginalised

neighbourhoods. They also promise to do more to address the rampant

gender-based violence during the pandemic and to create 24-hour

childcare to support women who are left at home with their children.

TRAINING WOMEN FOR POLITICS

Roberta Eugênio, from the non-profit group Instituto Alziras, which

trains women candidates on campaign and communication strategies, as

well as how electoral legislation and financing works, says that women

have always been engaged in politics.

But their involvement has mostly been in neighbourhood associations,

where they have fought for basic sanitation, healthcare, education and

childcare. “What we are seeing now is a recognition of, and support

for, their formal involvement,” she said.

This year alone, Eugênio has coached almost 2,000 pre-candidates,

from a wide spectrum of political parties, on how to run for the

position of councillor or mayor in the upcoming elections. Half of the

trainees were Black women and many will run for office in some of

Brazil’s remotest regions.

Eugênio feared that the impact of COVID-19 would deter women from

campaigning, but she was encouraged by the high turnout for her

course. “Municipal elections are a gateway for women to access

formal politics,” she explained.

Instituto Alziras research found that towns run by women mayors were

almost 50% more likely to have gender parity in local government

offices.

“Even if the number of women elected in a few weeks increases by

just 1%, 2% or even 3%, which seems like a little, the multiplier

effect is big,” she explained. Many more women now have the tools

and networks to continue the race until, eventually, they make a

breakthrough.

According to the Superior Electoral Court

[[link removed]] (which regulates Brazil’s electoral

system), [[link removed]] 34% of candidates registered to

contest city council positions are women, of which 16.8% are Black.

The race for mayors isn’t as promising: only 13% of candidates are

women, of which 4.5 % are Black.

For the last decade, Brazil has required that 30% of each party’s

candidates be women, but that has done little to boost the

participation of women in state and national legislatures. Parties

often ran ‘ghost’ women candidates just to meet the quota and gave

them little support or resources.

Another law, passed shortly before the 2018 elections, required

parties to allocate at least 30% of taxpayer-financed electoral funds

to women. But again, in many instances, parties used women candidacies

to siphon money to male candidates.

Ana Carolina Lourenço from Mulheres Negras Decidem notes that quotas

for women do not necessarily mean greater inclusion of Black women,

who are still the most underrepresented group in Brazilian politics.

But she acknowledges that laws passed post-2015 to boost women's

political participation have helped to empower women within political

parties, and increase accountability and the involvement of civil

society.

BACKLASH AND HATE SPEECH

Ironically, as Black women in politics gain visibility and collect

victories, so does Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-rights agenda, which

impacts them disproportionately.

“Bolsonaro’s politics and speech clash directly and obviously with

the Black women's movement,” said Lourenço. “All the public

policies that his government destroys, or enacts, affect our

priorities, which include defending human rights as well as

mainstreaming race and gender in public policies.”

Violence against women running for office is also on the rise. A few

days ago, federal representative, Talíria Petrone, said she had

received death threats. “Attacks on women and Black bodies should

not be normalised in any context, including in the exercise of

parliamentary mandates and in electoral processes,” Petrone said

[[link removed]] in

a statement urging followers to sign an international petition

[[link removed]] calling

for her protection. Since 2017, when she became a council member in

the state of Rio de Janeiro at the same time as the late Marielle

Franco, Petrone has received regular threats.

A recent study by Instituto Alziras found that violence – along with

inadequate funding and lack of visibility in the media – was one of

the key factors still keeping women out of politics. “Violence

against female political candidates starts with minor provocations,

which are considered harmless. And then it escalates,” explained

Eugênio.

Training for prospective candidates by women’s groups usually

includes advice on online security and what to do if they become

victims of different kinds of violence.

Rosa recalls a string of hate and racist messages that appeared in the

chat during an online meeting of Mulheres Negras Sim in late

September.

“I fear that this direct violence on my body may continue,” she

said. “You see, Bolsonaro’s hate policy does not suit us. We need

to bring our culture into politics, so that it stops being grey and

starts to reflect our population.”

[_Bruna Pereira is a feminist anti-racist activist and a founding

member of the Feminists for Rights, Equality and Empowerment (FREE)

Network. She is the founder and coordinator of Black Women's Study

Group at the University of Brasilia, Brazil. Macarena Aguilar is a

women´s rights advocate and a founding member of the FREE Network.

Previously she worked for the Association of Women´s Rights in

Development (AWID) as Interim Director of Communications and Senior

Online Communications Manager. She is the co-founder of Small World

Stories and their Digital and Business Development Director._]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV