Email

Who’s been hardest hit by the pandemic, and will they make their voices heard on Election Day?

| From | Thea Lee, Economic Policy Institute <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Who’s been hardest hit by the pandemic, and will they make their voices heard on Election Day? |

| Date | October 31, 2020 1:37 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[link removed]

Friend,

We are just days away from the most important election in our lifetimes. Will we elect leaders who fight for the rights and wages of working people, or maintain a status quo that has left behind far too many working people and families?

Below, take a look at EPI’s latest blog ([link removed]) , which discusses who has been hardest hit by the COVID-19 recession and how these people can influence the outcome of the election.

If you haven’t yet cast your ballot, click here for a voter checklist that will help you make your voice heard between now and Election Day. ([link removed])

Forward this email to family and friends and encourage them to vote on or before November 3rd.

Thank you,

Thea Lee

President, Economic Policy Institute

By EPI’s Krista Faries ([link removed]) and Kayla Blado ([link removed])

Black, Hispanic, and young workers have been left behind by policymakers, but will they vote?

EPI research finds that Black ([link removed]) , Hispanic ([link removed]) , and young workers ([link removed]) are among those hit hardest by the COVID-19 recession—facing unemployment rates far beyond what white workers and older workers are facing. The resulting economic challenges—including food insecurity ([link removed]) and the threat of eviction ([link removed]) , among others ([link removed]) —will compound if additional relief doesn’t come soon. In addition to economic threats, the health threats of the coronavirus pandemic have

affected communities of color ([link removed]) far worse than white communities.

Young adults and Black and Hispanic citizens have also been historically underrepresented at the polls, for a variety of reasons that we explore below. But could that change in 2020?

** Historical voting trends among the Black, Hispanic, and young adult populations

------------------------------------------------------------

Black voters have faced a 150-year struggle against voter ([link removed]) intimidation ([link removed]) and suppression ([link removed]) tactics ([link removed]) and the multilayered legacies of slavery ([link removed]) . Black Americans are also disproportionately disenfranchised ([link removed]) by state laws that ban convicted felons from voting—even, in some states, after they have served their full sentence. Given the U.S.’s high incarceration rate ([link removed])

and systemic racism ([link removed]) in the criminal justice system, this is just one more way the Black vote is suppressed.

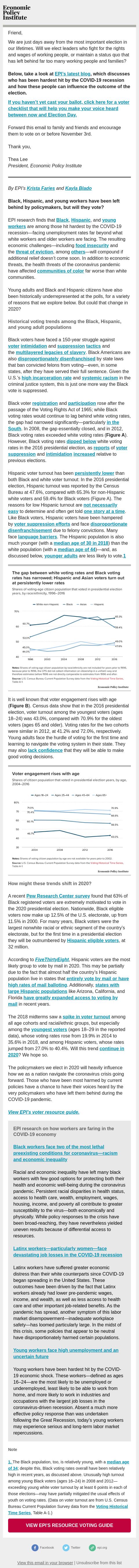

Black voter registration ([link removed]) and participation ([link removed]) rose after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; while Black voting rates would continue to lag behind white voting rates, the gap had narrowed significantly—particularly in the South ([link removed]) . In 2008, the gap essentially closed, and in 2012, Black voting rates exceeded white voting rates (Figure A). However, Black voting rates dipped below ([link removed]) white voting rates in the 2016 presidential election, as reports

([link removed]) of voter suppression ([link removed]) and intimidation ([link removed]) increased ([link removed]) relative to previous elections.

Hispanic voter turnout has been persistently lower ([link removed]) than both Black and white voter turnout: In the 2016 presidential election, Hispanic turnout was reported by the Census Bureau at 47.6%, compared with 65.3% for non-Hispanic white voters and 59.4% for Black voters (Figure A). The reasons for low Hispanic turnout are not necessarily easy ([link removed]) to determine and often get told one story at a time ([link removed]) . Like Black voters, Hispanic voters have been hampered by voter suppression efforts ([link removed]) and face disproportionate disenfranchisement

([link removed]) due to felony convictions. Many face language barriers ([link removed]) . The Hispanic population is also much younger (with a median age of 30 in 2018 ([link removed]) ) than the white population (with a median age of 44 ([link removed]) )—and, as discussed below, younger adults ([link removed]) are less likely to vote.1 ([link removed])

[link removed]

It is well known that voter engagement rises with age (Figure B). Census data show that in the 2016 presidential election, voter turnout among the youngest voters (ages 18–24) was 43.0%, compared with 70.9% for the oldest voters (ages 65 and older). Voting rates for the two cohorts were similar in 2012, at 41.2% and 72.0%, respectively. Young adults face the hurdle of voting for the first time and learning to navigate the voting system in their state. They may also lack confidence ([link removed]) that they will be able to make good voting decisions.

[link removed]

** How might these trends shift in 2020?

------------------------------------------------------------

A recent Pew Research Center survey ([link removed]) found that 63% of Black registered voters are extremely motivated to vote in the 2020 presidential election. Nationwide, Black eligible voters now make up 12.5% of the U.S. electorate, up from 11.5% in 2000. For many years, Black voters were the largest nonwhite racial or ethnic segment of the country’s electorate, but for the first time in a presidential election they will be outnumbered by Hispanic eligible voters ([link removed]) , at 32 million.

According to FiveThirtyEight ([link removed]) , Hispanic voters are the most likely group to vote by mail in 2020. This may be partially due to the fact that almost half the country’s Hispanic population live in states that entirely vote by mail or have high rates of mail balloting ([link removed]) . Additionally, states with large Hispanic populations ([link removed]) like Arizona, California, and Florida have greatly expanded access to voting by mail ([link removed]) in recent years.

The 2018 midterms saw a spike in voter turnout ([link removed]) among all age cohorts and racial/ethnic groups, but especially among the youngest voters ([link removed]) (ages 18–29 in the reported data), whose voting rates rose from 19.9% in 2014 to 35.6% in 2018, and among Hispanic voters, whose rates jumped from 27.0% to 40.4%. Will this trend continue in 2020 ([link removed]) ? We hope so.

The policymakers we elect in 2020 will heavily influence how we as a nation navigate the coronavirus crisis going forward. Those who have been most harmed by current policies have a chance to have their voices heard by the very policymakers who have left them behind during the COVID-19 pandemic.

View EPI’s voter resource guide. ([link removed])

** EPI research on how workers are faring in the COVID-19 economy

------------------------------------------------------------

Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—racism and economic inequality ([link removed])

Racial and economic inequality have left many black workers with few good options for protecting both their health and economic well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Persistent racial disparities in health status, access to health care, wealth, employment, wages, housing, income, and poverty all contribute to greater susceptibility to the virus—both economically and physically. While policy responses to the crisis have been broad-reaching, they have nevertheless yielded uneven results because of differential access to resources.

Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession ([link removed])

Latinx workers have suffered greater economic distress than their white counterparts since COVID-19 began spreading in the United States. These outcomes have been driven by the fact that Latinx workers already had lower pre-pandemic wages, income, and wealth, as well as less access to health care and other important job-related benefits. As the pandemic has spread, another symptom of this labor market disempowerment—inadequate workplace safety—has loomed particularly large. In the midst of this crisis, some policies that appear to be neutral have disproportionately harmed certain populations.

Young workers face high unemployment and an uncertain future ([link removed])

Young workers have been hardest hit by the COVID-19 economic shock. These workers—defined as ages 16–24—are the most likely to be unemployed or underemployed, least likely to be able to work from home, and more likely to work in industries and occupations with the largest job losses in the coronavirus-driven recession. Absent a much more effective policy response than was undertaken following the Great Recession, today’s young workers may experience serious and long-term labor market repercussions.

** Note

------------------------------------------------------------

1. ([link removed]) The Black population, too, is relatively young, with a median age of 34 ([link removed]) ; despite this, Black voting rates overall have been relatively high in recent years, as discussed above. Unusually high turnout among young Black voters (ages 16–24) in 2008 and 2012—exceeding young white voter turnout by at least 6 points in each of those elections—may have partially mitigated the usual effects of youth on voting rates. (Data on voter turnout are from U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey data from the Voting Historical Time Series ([link removed]) , Table A-1.)

VIEW EPI'S RESOURCE VOTING GUIDE ([link removed])

============================================================

** Facebook ([link removed])

** Facebook ([link removed])

** Twitter ([link removed])

** Twitter ([link removed])

** epi.org ([link removed])

** epi.org ([link removed])

** View this email in your browser ([link removed])

| ** Unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

Friend,

We are just days away from the most important election in our lifetimes. Will we elect leaders who fight for the rights and wages of working people, or maintain a status quo that has left behind far too many working people and families?

Below, take a look at EPI’s latest blog ([link removed]) , which discusses who has been hardest hit by the COVID-19 recession and how these people can influence the outcome of the election.

If you haven’t yet cast your ballot, click here for a voter checklist that will help you make your voice heard between now and Election Day. ([link removed])

Forward this email to family and friends and encourage them to vote on or before November 3rd.

Thank you,

Thea Lee

President, Economic Policy Institute

By EPI’s Krista Faries ([link removed]) and Kayla Blado ([link removed])

Black, Hispanic, and young workers have been left behind by policymakers, but will they vote?

EPI research finds that Black ([link removed]) , Hispanic ([link removed]) , and young workers ([link removed]) are among those hit hardest by the COVID-19 recession—facing unemployment rates far beyond what white workers and older workers are facing. The resulting economic challenges—including food insecurity ([link removed]) and the threat of eviction ([link removed]) , among others ([link removed]) —will compound if additional relief doesn’t come soon. In addition to economic threats, the health threats of the coronavirus pandemic have

affected communities of color ([link removed]) far worse than white communities.

Young adults and Black and Hispanic citizens have also been historically underrepresented at the polls, for a variety of reasons that we explore below. But could that change in 2020?

** Historical voting trends among the Black, Hispanic, and young adult populations

------------------------------------------------------------

Black voters have faced a 150-year struggle against voter ([link removed]) intimidation ([link removed]) and suppression ([link removed]) tactics ([link removed]) and the multilayered legacies of slavery ([link removed]) . Black Americans are also disproportionately disenfranchised ([link removed]) by state laws that ban convicted felons from voting—even, in some states, after they have served their full sentence. Given the U.S.’s high incarceration rate ([link removed])

and systemic racism ([link removed]) in the criminal justice system, this is just one more way the Black vote is suppressed.

Black voter registration ([link removed]) and participation ([link removed]) rose after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; while Black voting rates would continue to lag behind white voting rates, the gap had narrowed significantly—particularly in the South ([link removed]) . In 2008, the gap essentially closed, and in 2012, Black voting rates exceeded white voting rates (Figure A). However, Black voting rates dipped below ([link removed]) white voting rates in the 2016 presidential election, as reports

([link removed]) of voter suppression ([link removed]) and intimidation ([link removed]) increased ([link removed]) relative to previous elections.

Hispanic voter turnout has been persistently lower ([link removed]) than both Black and white voter turnout: In the 2016 presidential election, Hispanic turnout was reported by the Census Bureau at 47.6%, compared with 65.3% for non-Hispanic white voters and 59.4% for Black voters (Figure A). The reasons for low Hispanic turnout are not necessarily easy ([link removed]) to determine and often get told one story at a time ([link removed]) . Like Black voters, Hispanic voters have been hampered by voter suppression efforts ([link removed]) and face disproportionate disenfranchisement

([link removed]) due to felony convictions. Many face language barriers ([link removed]) . The Hispanic population is also much younger (with a median age of 30 in 2018 ([link removed]) ) than the white population (with a median age of 44 ([link removed]) )—and, as discussed below, younger adults ([link removed]) are less likely to vote.1 ([link removed])

[link removed]

It is well known that voter engagement rises with age (Figure B). Census data show that in the 2016 presidential election, voter turnout among the youngest voters (ages 18–24) was 43.0%, compared with 70.9% for the oldest voters (ages 65 and older). Voting rates for the two cohorts were similar in 2012, at 41.2% and 72.0%, respectively. Young adults face the hurdle of voting for the first time and learning to navigate the voting system in their state. They may also lack confidence ([link removed]) that they will be able to make good voting decisions.

[link removed]

** How might these trends shift in 2020?

------------------------------------------------------------

A recent Pew Research Center survey ([link removed]) found that 63% of Black registered voters are extremely motivated to vote in the 2020 presidential election. Nationwide, Black eligible voters now make up 12.5% of the U.S. electorate, up from 11.5% in 2000. For many years, Black voters were the largest nonwhite racial or ethnic segment of the country’s electorate, but for the first time in a presidential election they will be outnumbered by Hispanic eligible voters ([link removed]) , at 32 million.

According to FiveThirtyEight ([link removed]) , Hispanic voters are the most likely group to vote by mail in 2020. This may be partially due to the fact that almost half the country’s Hispanic population live in states that entirely vote by mail or have high rates of mail balloting ([link removed]) . Additionally, states with large Hispanic populations ([link removed]) like Arizona, California, and Florida have greatly expanded access to voting by mail ([link removed]) in recent years.

The 2018 midterms saw a spike in voter turnout ([link removed]) among all age cohorts and racial/ethnic groups, but especially among the youngest voters ([link removed]) (ages 18–29 in the reported data), whose voting rates rose from 19.9% in 2014 to 35.6% in 2018, and among Hispanic voters, whose rates jumped from 27.0% to 40.4%. Will this trend continue in 2020 ([link removed]) ? We hope so.

The policymakers we elect in 2020 will heavily influence how we as a nation navigate the coronavirus crisis going forward. Those who have been most harmed by current policies have a chance to have their voices heard by the very policymakers who have left them behind during the COVID-19 pandemic.

View EPI’s voter resource guide. ([link removed])

** EPI research on how workers are faring in the COVID-19 economy

------------------------------------------------------------

Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—racism and economic inequality ([link removed])

Racial and economic inequality have left many black workers with few good options for protecting both their health and economic well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Persistent racial disparities in health status, access to health care, wealth, employment, wages, housing, income, and poverty all contribute to greater susceptibility to the virus—both economically and physically. While policy responses to the crisis have been broad-reaching, they have nevertheless yielded uneven results because of differential access to resources.

Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession ([link removed])

Latinx workers have suffered greater economic distress than their white counterparts since COVID-19 began spreading in the United States. These outcomes have been driven by the fact that Latinx workers already had lower pre-pandemic wages, income, and wealth, as well as less access to health care and other important job-related benefits. As the pandemic has spread, another symptom of this labor market disempowerment—inadequate workplace safety—has loomed particularly large. In the midst of this crisis, some policies that appear to be neutral have disproportionately harmed certain populations.

Young workers face high unemployment and an uncertain future ([link removed])

Young workers have been hardest hit by the COVID-19 economic shock. These workers—defined as ages 16–24—are the most likely to be unemployed or underemployed, least likely to be able to work from home, and more likely to work in industries and occupations with the largest job losses in the coronavirus-driven recession. Absent a much more effective policy response than was undertaken following the Great Recession, today’s young workers may experience serious and long-term labor market repercussions.

** Note

------------------------------------------------------------

1. ([link removed]) The Black population, too, is relatively young, with a median age of 34 ([link removed]) ; despite this, Black voting rates overall have been relatively high in recent years, as discussed above. Unusually high turnout among young Black voters (ages 16–24) in 2008 and 2012—exceeding young white voter turnout by at least 6 points in each of those elections—may have partially mitigated the usual effects of youth on voting rates. (Data on voter turnout are from U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey data from the Voting Historical Time Series ([link removed]) , Table A-1.)

VIEW EPI'S RESOURCE VOTING GUIDE ([link removed])

============================================================

** Facebook ([link removed])

** Facebook ([link removed])

** Twitter ([link removed])

** Twitter ([link removed])

** epi.org ([link removed])

** epi.org ([link removed])

** View this email in your browser ([link removed])

| ** Unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

Message Analysis

- Sender: Economic Policy Institute

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- MailChimp