Email

New data: Coronavirus isn't over, but most jail populations are rising again

| From | Peter Wagner <[email protected]> |

| Subject | New data: Coronavirus isn't over, but most jail populations are rising again |

| Date | August 5, 2020 6:22 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

71% of jails we've been tracking saw recent population increases

Prison Policy Initiative updates for August 5, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Jails and prisons have reduced their populations in the face of the pandemic, but not enough to save lives [[link removed]] Our updated analysis finds that the initial efforts to reduce jail populations have slowed, while the small drops in state prison populations are still too little to save lives. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Peter Wagner

At a time when more new cases of the coronavirus are being reported each day, state and local governments should be redoubling their efforts to reduce the number of people in prisons and jails, where social distancing is impossible [[link removed]] and the cycle of people in and out of the facility is constant. But our most recent analysis of data from hundreds of counties across the country shows that efforts to reduce jail populations have actually slowed - and even reversed in some places.

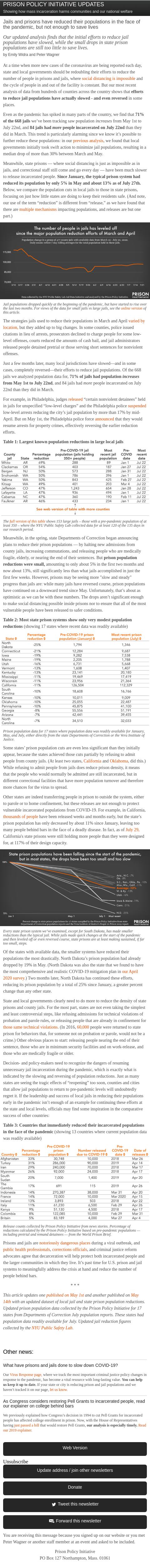

Even as the pandemic has spiked in many parts of the country, we find that 71% of the 668 jails we’ve been tracking saw population increases from May 1st to July 22nd, and 84 jails had more people incarcerated on July 22nd than they did in March. This trend is particularly alarming since we know it’s possible to further reduce these populations: in our previous analysis [[link removed]], we found that local governments initially took swift action to minimize jail populations, resulting in a median drop of more than 30% between March and May.

Meanwhile, state prisons — where social distancing is just as impossible as in jails, and correctional staff still come and go every day — have been much slower to release incarcerated people. Since January, the typical prison system had reduced its population by only 5% in May and about 13% as of July 27th. Below, we compare the population cuts in local jails to those in state prisons, focusing on just how little states are doing to keep their residents safe. (And note, our use of the term “reduction” is different from “release,” as we have found that there are multiple mechanisms [[link removed]] impacting populations, and releases are but one part.)

Jail populations dropped quickly at the beginning of the pandemic, but have started to rise over the last two months. For views of the data for small jails vs large jails, see the online version [[link removed]] of this article.

The strategies jails used to reduce their populations in March and April varied by location, [[link removed]] but they added up to big changes. In some counties, police issued citations in lieu of arrests, prosecutors declined to charge people for some low-level offenses, courts reduced the amounts of cash bail, and jail administrators released people detained pretrial or those serving short sentences for nonviolent offenses.

Just a few months later, many local jurisdictions have slowed—and in some cases, completely reversed—their efforts to reduce jail populations. Of the 668 jails we analyzed population data for, 71% of jails had population increases from May 1st to July 22nd, and 84 jails had more people incarcerated on July 22nd than they did in March.

For example, in Philadelphia, judges released [[link removed]] “certain nonviolent detainees” held in jails for unspecified “low-level charges” and the Philadelphia police suspended [[link removed]] low-level arrests reducing the city’s jail population by more than 17% by mid-April. But on May 1st, the Philadelphia police force announced [[link removed]] that they would resume arrests for property crimes, effectively reversing the earlier reduction efforts.

Table 1: Largest known population reductions in large local jails

The full version of this table [[link removed]] shows 153 large jails – those with a pre-pandemic population of at least 350 – where the NYU Public Safety Lab collected data for at least 120 of the 135 days in our research period.

Meanwhile, in the spring, state Departments of Correction began announcing plans to reduce their prison populations — by halting new admissions from county jails, increasing commutations, and releasing people who are medically fragile, elderly, or nearing the end of their sentences. But prison population reductions were small, amounting to only about 5% in the first two months and now about 13%, still significantly less than what jails accomplished in just the first few weeks. However, prisons may be seeing more "slow and steady" progress than jails are: while many jails have reversed course, prison populations have continued on a downward trend since May. Unfortunately, that’s about as optimistic as we can be with these numbers. The drops aren’t significant enough to make social distancing possible inside prisons nor to ensure that all of the most vulnerable people have been released to safer conditions.

Table 2: Most state prison systems show only very modest population reductions (showing 17 states where recent data was readily available)

Prison population data for 17 states where population data was readily available for January, May, and July, either directly from the state Departments of Correction or the Vera Institute of Justice.

Some states’ prison population cuts are even less significant than they initially appear, because the states achieved those cuts partially by refusing to admit people from county jails. (At least two states, California [[link removed]] and Oklahoma [[link removed]], did this.) While refusing to admit people from jails does reduce prison density, it means that the people who would normally be admitted are still incarcerated, but in different correctional facilities that have more population turnover and therefore more chances for the virus to spread.

Other states are indeed transferring people in prison to outside the system, either to parole or to home confinement, but these releases are not enough to protect vulnerable incarcerated populations from COVID-19. For example, in California, thousands of people [[link removed]] have been released weeks and months early, but the state’s prison population has only decreased by about 11% since January, leaving too many people behind bars in the face of a deadly disease. In fact, as of July 29, [[link removed]] California's state prisons were still holding more people than they were designed for, at 117% of their design capacity.

Every state prison system we’ve examined, except for South Dakota, has made smaller reductions than the typical jail. While jails made quick changes at the start of the pandemic and then leveled off or even reversed course, state prisons are at least making sustained, if far too small, steps.

Of the states with available data, the smaller systems have reduced their populations the most drastically. North Dakota’s prison population had already dropped by 19% in May. (North Dakota was also the state that we found to have the most comprehensive and realistic COVID-19 mitigation plan in our April 2020 survey [[link removed]].) Two months later, North Dakota has continued these efforts, reducing its prison population by a total of 25% since January, a greater percent change than any other state.

State and local governments clearly need to do more to reduce the density of state prisons and county jails. For the most part, states are not even taking the simplest and least controversial steps, like refusing admissions for technical violations of probation and parole rules, or releasing people that are already in confinement for those same technical violations [[link removed]]. (In 2016, 60,000 [[link removed]] people were returned to state prison for behaviors that, for someone not on probation or parole, would not be a crime.) Other obvious places to start: releasing people nearing the end of their sentence, those who are in minimum security facilities and on work-release, and those who are medically fragile or older.

Decision- and policy-makers need to recognize the dangers of resuming unnecessary jail incarceration during the pandemic, which is exactly what is indicated by the slowing and reversing of population reductions. Just as many states are seeing the tragic effects of “reopening” too soon, counties and cities that allow jail populations to return to pre-pandemic levels will undoubtedly regret it. If the leadership and success of local jails in reducing their populations early in the pandemic isn’t enough of an example for continuing these efforts at the state and local levels, officials may find some inspiration in the comparative success of other countries:

Table 3: Countries that immediately reduced their incarcerated populations in the face of the pandemic (showing 13 countries where current population data was readily available)

Release counts collected by Prison Policy Initiative from news stories. Percentage of reductions calculated by the Prison Policy Initiative based on pre-pandemic populations — including pretrial and remand detainees — from the World Prison Brief.

Prisons and jails are notoriously dangerous places [[link removed]] during a viral outbreak, and public health professionals [[link removed]], corrections officials [[link removed]], and criminal justice reform advocates agree that decarceration will help protect both incarcerated people and the larger communities in which they live. It’s past time for U.S. prison and jail systems to meaningfully address the crisis at hand and reduce the number of people behind bars.

* * *

This article updates one published on May 1st [[link removed]] and another published on May 14th [[link removed]] with an updated dataset of local jail and state prison population reductions. Updated prison population data collected by the Prison Policy Initiative for 17 states from Departments of Correction July population reports. These states had population data readily available for July. Updated jail reduction figures collected by the NYU Public Safety Lab [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: What have prisons and jails done to slow down COVID-19? [[link removed]]

Our Virus Response page, [[link removed]] where we track the most important criminal justice policy changes in response to the pandemic, has become a vital resource with long-lasting value. You can help us keep it up to date. If your state or city is reducing prison and jail populations and we haven’t tracked it on our page, let us know. [[link removed]]

As Congress considers restoring Pell Grants to incarcerated people, read our explainer on college behind bars [[link removed]]

We previously explained how Congress’s decision in 1994 to cut Pell Grants for incarcerated people has affected college enrollment in prison. Now, with the House of Representatives having just passed a bill [[link removed]] that would restore Pell Grants, our analysis is especially timely. Read our 2019 explainer. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for August 5, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Jails and prisons have reduced their populations in the face of the pandemic, but not enough to save lives [[link removed]] Our updated analysis finds that the initial efforts to reduce jail populations have slowed, while the small drops in state prison populations are still too little to save lives. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Peter Wagner

At a time when more new cases of the coronavirus are being reported each day, state and local governments should be redoubling their efforts to reduce the number of people in prisons and jails, where social distancing is impossible [[link removed]] and the cycle of people in and out of the facility is constant. But our most recent analysis of data from hundreds of counties across the country shows that efforts to reduce jail populations have actually slowed - and even reversed in some places.

Even as the pandemic has spiked in many parts of the country, we find that 71% of the 668 jails we’ve been tracking saw population increases from May 1st to July 22nd, and 84 jails had more people incarcerated on July 22nd than they did in March. This trend is particularly alarming since we know it’s possible to further reduce these populations: in our previous analysis [[link removed]], we found that local governments initially took swift action to minimize jail populations, resulting in a median drop of more than 30% between March and May.

Meanwhile, state prisons — where social distancing is just as impossible as in jails, and correctional staff still come and go every day — have been much slower to release incarcerated people. Since January, the typical prison system had reduced its population by only 5% in May and about 13% as of July 27th. Below, we compare the population cuts in local jails to those in state prisons, focusing on just how little states are doing to keep their residents safe. (And note, our use of the term “reduction” is different from “release,” as we have found that there are multiple mechanisms [[link removed]] impacting populations, and releases are but one part.)

Jail populations dropped quickly at the beginning of the pandemic, but have started to rise over the last two months. For views of the data for small jails vs large jails, see the online version [[link removed]] of this article.

The strategies jails used to reduce their populations in March and April varied by location, [[link removed]] but they added up to big changes. In some counties, police issued citations in lieu of arrests, prosecutors declined to charge people for some low-level offenses, courts reduced the amounts of cash bail, and jail administrators released people detained pretrial or those serving short sentences for nonviolent offenses.

Just a few months later, many local jurisdictions have slowed—and in some cases, completely reversed—their efforts to reduce jail populations. Of the 668 jails we analyzed population data for, 71% of jails had population increases from May 1st to July 22nd, and 84 jails had more people incarcerated on July 22nd than they did in March.

For example, in Philadelphia, judges released [[link removed]] “certain nonviolent detainees” held in jails for unspecified “low-level charges” and the Philadelphia police suspended [[link removed]] low-level arrests reducing the city’s jail population by more than 17% by mid-April. But on May 1st, the Philadelphia police force announced [[link removed]] that they would resume arrests for property crimes, effectively reversing the earlier reduction efforts.

Table 1: Largest known population reductions in large local jails

The full version of this table [[link removed]] shows 153 large jails – those with a pre-pandemic population of at least 350 – where the NYU Public Safety Lab collected data for at least 120 of the 135 days in our research period.

Meanwhile, in the spring, state Departments of Correction began announcing plans to reduce their prison populations — by halting new admissions from county jails, increasing commutations, and releasing people who are medically fragile, elderly, or nearing the end of their sentences. But prison population reductions were small, amounting to only about 5% in the first two months and now about 13%, still significantly less than what jails accomplished in just the first few weeks. However, prisons may be seeing more "slow and steady" progress than jails are: while many jails have reversed course, prison populations have continued on a downward trend since May. Unfortunately, that’s about as optimistic as we can be with these numbers. The drops aren’t significant enough to make social distancing possible inside prisons nor to ensure that all of the most vulnerable people have been released to safer conditions.

Table 2: Most state prison systems show only very modest population reductions (showing 17 states where recent data was readily available)

Prison population data for 17 states where population data was readily available for January, May, and July, either directly from the state Departments of Correction or the Vera Institute of Justice.

Some states’ prison population cuts are even less significant than they initially appear, because the states achieved those cuts partially by refusing to admit people from county jails. (At least two states, California [[link removed]] and Oklahoma [[link removed]], did this.) While refusing to admit people from jails does reduce prison density, it means that the people who would normally be admitted are still incarcerated, but in different correctional facilities that have more population turnover and therefore more chances for the virus to spread.

Other states are indeed transferring people in prison to outside the system, either to parole or to home confinement, but these releases are not enough to protect vulnerable incarcerated populations from COVID-19. For example, in California, thousands of people [[link removed]] have been released weeks and months early, but the state’s prison population has only decreased by about 11% since January, leaving too many people behind bars in the face of a deadly disease. In fact, as of July 29, [[link removed]] California's state prisons were still holding more people than they were designed for, at 117% of their design capacity.

Every state prison system we’ve examined, except for South Dakota, has made smaller reductions than the typical jail. While jails made quick changes at the start of the pandemic and then leveled off or even reversed course, state prisons are at least making sustained, if far too small, steps.

Of the states with available data, the smaller systems have reduced their populations the most drastically. North Dakota’s prison population had already dropped by 19% in May. (North Dakota was also the state that we found to have the most comprehensive and realistic COVID-19 mitigation plan in our April 2020 survey [[link removed]].) Two months later, North Dakota has continued these efforts, reducing its prison population by a total of 25% since January, a greater percent change than any other state.

State and local governments clearly need to do more to reduce the density of state prisons and county jails. For the most part, states are not even taking the simplest and least controversial steps, like refusing admissions for technical violations of probation and parole rules, or releasing people that are already in confinement for those same technical violations [[link removed]]. (In 2016, 60,000 [[link removed]] people were returned to state prison for behaviors that, for someone not on probation or parole, would not be a crime.) Other obvious places to start: releasing people nearing the end of their sentence, those who are in minimum security facilities and on work-release, and those who are medically fragile or older.

Decision- and policy-makers need to recognize the dangers of resuming unnecessary jail incarceration during the pandemic, which is exactly what is indicated by the slowing and reversing of population reductions. Just as many states are seeing the tragic effects of “reopening” too soon, counties and cities that allow jail populations to return to pre-pandemic levels will undoubtedly regret it. If the leadership and success of local jails in reducing their populations early in the pandemic isn’t enough of an example for continuing these efforts at the state and local levels, officials may find some inspiration in the comparative success of other countries:

Table 3: Countries that immediately reduced their incarcerated populations in the face of the pandemic (showing 13 countries where current population data was readily available)

Release counts collected by Prison Policy Initiative from news stories. Percentage of reductions calculated by the Prison Policy Initiative based on pre-pandemic populations — including pretrial and remand detainees — from the World Prison Brief.

Prisons and jails are notoriously dangerous places [[link removed]] during a viral outbreak, and public health professionals [[link removed]], corrections officials [[link removed]], and criminal justice reform advocates agree that decarceration will help protect both incarcerated people and the larger communities in which they live. It’s past time for U.S. prison and jail systems to meaningfully address the crisis at hand and reduce the number of people behind bars.

* * *

This article updates one published on May 1st [[link removed]] and another published on May 14th [[link removed]] with an updated dataset of local jail and state prison population reductions. Updated prison population data collected by the Prison Policy Initiative for 17 states from Departments of Correction July population reports. These states had population data readily available for July. Updated jail reduction figures collected by the NYU Public Safety Lab [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: What have prisons and jails done to slow down COVID-19? [[link removed]]

Our Virus Response page, [[link removed]] where we track the most important criminal justice policy changes in response to the pandemic, has become a vital resource with long-lasting value. You can help us keep it up to date. If your state or city is reducing prison and jail populations and we haven’t tracked it on our page, let us know. [[link removed]]

As Congress considers restoring Pell Grants to incarcerated people, read our explainer on college behind bars [[link removed]]

We previously explained how Congress’s decision in 1994 to cut Pell Grants for incarcerated people has affected college enrollment in prison. Now, with the House of Representatives having just passed a bill [[link removed]] that would restore Pell Grants, our analysis is especially timely. Read our 2019 explainer. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor