Email

On Redistricting

| From | Matt Royer from By the Ballot <[email protected]> |

| Subject | On Redistricting |

| Date | February 9, 2026 1:03 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

Virginia Democrats rolled out their proposed 10–1 redrawn congressional maps yesterday, capping off a months-long internal debate that followed the special session of the General Assembly called ahead of the 2025 election. For weeks, Election Twitter and Reddit threads had been ablaze with amateur and semi-professional mapmaking exercises promising everything from incremental Democratic gains to outright congressional domination. Meanwhile, Democratic leaders—most notably Senate Pro Tem L. Louise Lucas—were unapologetic about their goals, loudly and repeatedly rallying behind a simple message: “10 fucking 1.”

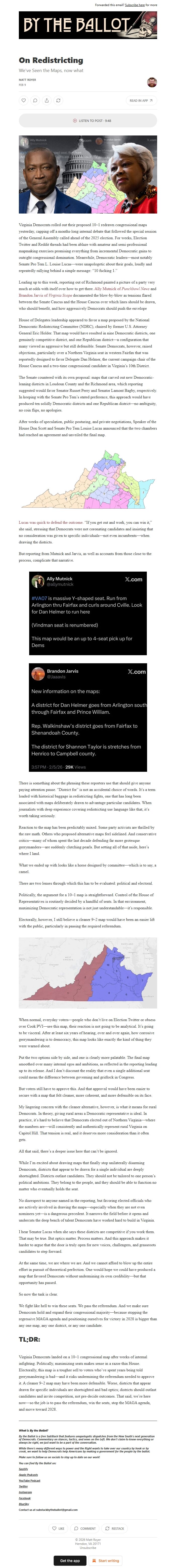

Leading up to this week, reporting out of Richmond painted a picture of a party very much at odds with itself over how to get there. Ally Mutnick of [ [link removed] ]Punchbowl News [ [link removed] ] [ [link removed] ]and Brandon Jarvis of [ [link removed] ]Virginia Scope [ [link removed] ] documented the blow-by-blow as tensions flared between the Senate Caucus and the House Caucus over which lines should be drawn, who should benefit, and how aggressively Democrats should push the envelope

House of Delegates leadership appeared to favor a map proposed by the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), chaired by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. That map would have resulted in nine Democratic districts, one genuinely competitive district, and one Republican district—a configuration that many viewed as aggressive but still defensible. Senate Democrats, however, raised objections, particularly over a Northern Virginia seat in western Fairfax that was reportedly designed to favor Delegate Dan Helmer, the current campaign chair of the House Caucus and a two-time congressional candidate in Virginia’s 10th District.

The Senate countered with its own proposal: maps that carved out new Democratic-leaning districts in Loudoun County and the Richmond area, which reporting suggested would favor Senator Russet Perry and Senator Lamont Bagby, respectively. In keeping with the Senate Pro Tem’s stated preference, this approach would have produced ten solidly Democratic districts and one Republican district—no ambiguity, no coin flips, no apologies.

After weeks of speculation, public posturing, and private negotiations, Speaker of the House Don Scott and Senate Pro Tem Louise Lucas announced that the two chambers had reached an agreement and unveiled the final map.

Lucas was quick to defend the outcome. [ [link removed] ] “If you get out and work, you can win it,” she said, stressing that Democrats were not coronating candidates and insisting that no consideration was given to specific individuals—not even incumbents—when drawing the districts.

But reporting from Mutnick and Jarvis, as well as accounts from those close to the process, complicate that narrative.

There is something about the phrasing these reporters use that should give anyone paying attention pause. “District for” is not an accidental choice of words. It’s a term loaded with historical baggage in redistricting fights, one that has long been associated with maps deliberately drawn to advantage particular candidates. When journalists with deep experience covering redistricting use language like that, it’s worth taking seriously.

Reaction to the map has been predictably mixed. Some party activists are thrilled by the raw math. Others who proposed alternative maps feel sidelined. And conservative critics—many of whom spent the last decade defending far more grotesque gerrymanders—are suddenly clutching pearls. But setting all of that aside, here’s where I land.

What we ended up with looks like a horse designed by committee—which is to say, a camel.

There are two lenses through which this has to be evaluated: political and electoral.

Politically, the argument for a 10–1 map is straightforward. Control of the House of Representatives is routinely decided by a handful of seats. In that environment, maximizing Democratic representation is not just understandable—it’s responsible.

Electorally, however, I still believe a cleaner 9–2 map would have been an easier lift with the public, particularly in passing the required referendum.

When normal, everyday voters—people who don’t live on Election Twitter or obsess over Cook PVI—see this map, their reaction is not going to be analytical. It’s going to be visceral. After at least six years of hearing, over and over again, how corrosive gerrymandering is to democracy, this map looks like exactly the kind of thing they were warned about.

Put the two options side by side, and one is clearly more palatable. The final map smoothed over many internal egos and ambitions, as reflected in the reporting leading up to its release. And I don’t discount the reality that even a single additional seat could mean the difference between governing and gridlock in Congress.

But voters still have to approve this. And that approval would have been easier to secure with a map that felt cleaner, more coherent, and more defensible on its face.

My lingering concern with the cleaner alternative, however, is what it means for rural Democrats. In theory, giving rural areas a Democratic representative is ideal. In practice, it’s hard to believe that Democrats elected out of Northern Virginia—where the numbers are—will consistently and authentically represent rural Virginia on Capitol Hill. That tension is real, and it deserves more consideration than it often gets.

All that said, there’s a deeper issue here that can’t be ignored.

While I’m excited about drawing maps that finally stop unilaterally disarming Democrats, districts that appear to be drawn for a single individual are deeply shortsighted. Districts outlast candidates. They should not be tailored to one person’s political ambitions. They belong to the people, and they should be able to function no matter who eventually holds the seat.

No disrespect to anyone named in the reporting, but favoring elected officials who are actively involved in drawing the maps—especially when they are not even nominees yet—is a dangerous precedent. It narrows the field before it opens and undercuts the deep bench of talent Democrats have worked hard to build in Virginia.

I hear Senator Lucas when she says these districts are competitive if you work them. That may be true. But optics matter. Process matters. And this approach makes it harder to argue that the door is truly open for new voices, challengers, and grassroots candidates to step forward.

At the same time, we are where we are. And we cannot afford to blow up the entire effort in pursuit of theoretical perfection. One would hope we could have produced a map that favored Democrats without undermining its own credibility—but that opportunity has passed.

So now the task is clear.

We fight like hell to win these seats. We pass the referendum. And we make sure Democrats hold and expand their congressional majority—because stopping the regressive MAGA agenda and positioning ourselves for victory in 2028 is bigger than any one map, any one district, or any one candidate.

TL;DR:

Virginia Democrats landed on a 10–1 congressional map after weeks of internal infighting. Politically, maximizing seats makes sense in a razor-thin House. Electorally, this map is a tougher sell to voters who’ve spent years being told gerrymandering is bad—and it risks undermining the referendum needed to approve it. A cleaner 9–2 map may have been more defensible. Worse, districts that appear drawn for specific individuals are shortsighted and bad optics; districts should outlast candidates and invite competition, not pre-decide outcomes. That said, we’re here now—so the job is to pass the referendum, win the seats, stop the MAGA agenda, and move toward 2028.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Virginia Democrats rolled out their proposed 10–1 redrawn congressional maps yesterday, capping off a months-long internal debate that followed the special session of the General Assembly called ahead of the 2025 election. For weeks, Election Twitter and Reddit threads had been ablaze with amateur and semi-professional mapmaking exercises promising everything from incremental Democratic gains to outright congressional domination. Meanwhile, Democratic leaders—most notably Senate Pro Tem L. Louise Lucas—were unapologetic about their goals, loudly and repeatedly rallying behind a simple message: “10 fucking 1.”

Leading up to this week, reporting out of Richmond painted a picture of a party very much at odds with itself over how to get there. Ally Mutnick of [ [link removed] ]Punchbowl News [ [link removed] ] [ [link removed] ]and Brandon Jarvis of [ [link removed] ]Virginia Scope [ [link removed] ] documented the blow-by-blow as tensions flared between the Senate Caucus and the House Caucus over which lines should be drawn, who should benefit, and how aggressively Democrats should push the envelope

House of Delegates leadership appeared to favor a map proposed by the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), chaired by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. That map would have resulted in nine Democratic districts, one genuinely competitive district, and one Republican district—a configuration that many viewed as aggressive but still defensible. Senate Democrats, however, raised objections, particularly over a Northern Virginia seat in western Fairfax that was reportedly designed to favor Delegate Dan Helmer, the current campaign chair of the House Caucus and a two-time congressional candidate in Virginia’s 10th District.

The Senate countered with its own proposal: maps that carved out new Democratic-leaning districts in Loudoun County and the Richmond area, which reporting suggested would favor Senator Russet Perry and Senator Lamont Bagby, respectively. In keeping with the Senate Pro Tem’s stated preference, this approach would have produced ten solidly Democratic districts and one Republican district—no ambiguity, no coin flips, no apologies.

After weeks of speculation, public posturing, and private negotiations, Speaker of the House Don Scott and Senate Pro Tem Louise Lucas announced that the two chambers had reached an agreement and unveiled the final map.

Lucas was quick to defend the outcome. [ [link removed] ] “If you get out and work, you can win it,” she said, stressing that Democrats were not coronating candidates and insisting that no consideration was given to specific individuals—not even incumbents—when drawing the districts.

But reporting from Mutnick and Jarvis, as well as accounts from those close to the process, complicate that narrative.

There is something about the phrasing these reporters use that should give anyone paying attention pause. “District for” is not an accidental choice of words. It’s a term loaded with historical baggage in redistricting fights, one that has long been associated with maps deliberately drawn to advantage particular candidates. When journalists with deep experience covering redistricting use language like that, it’s worth taking seriously.

Reaction to the map has been predictably mixed. Some party activists are thrilled by the raw math. Others who proposed alternative maps feel sidelined. And conservative critics—many of whom spent the last decade defending far more grotesque gerrymanders—are suddenly clutching pearls. But setting all of that aside, here’s where I land.

What we ended up with looks like a horse designed by committee—which is to say, a camel.

There are two lenses through which this has to be evaluated: political and electoral.

Politically, the argument for a 10–1 map is straightforward. Control of the House of Representatives is routinely decided by a handful of seats. In that environment, maximizing Democratic representation is not just understandable—it’s responsible.

Electorally, however, I still believe a cleaner 9–2 map would have been an easier lift with the public, particularly in passing the required referendum.

When normal, everyday voters—people who don’t live on Election Twitter or obsess over Cook PVI—see this map, their reaction is not going to be analytical. It’s going to be visceral. After at least six years of hearing, over and over again, how corrosive gerrymandering is to democracy, this map looks like exactly the kind of thing they were warned about.

Put the two options side by side, and one is clearly more palatable. The final map smoothed over many internal egos and ambitions, as reflected in the reporting leading up to its release. And I don’t discount the reality that even a single additional seat could mean the difference between governing and gridlock in Congress.

But voters still have to approve this. And that approval would have been easier to secure with a map that felt cleaner, more coherent, and more defensible on its face.

My lingering concern with the cleaner alternative, however, is what it means for rural Democrats. In theory, giving rural areas a Democratic representative is ideal. In practice, it’s hard to believe that Democrats elected out of Northern Virginia—where the numbers are—will consistently and authentically represent rural Virginia on Capitol Hill. That tension is real, and it deserves more consideration than it often gets.

All that said, there’s a deeper issue here that can’t be ignored.

While I’m excited about drawing maps that finally stop unilaterally disarming Democrats, districts that appear to be drawn for a single individual are deeply shortsighted. Districts outlast candidates. They should not be tailored to one person’s political ambitions. They belong to the people, and they should be able to function no matter who eventually holds the seat.

No disrespect to anyone named in the reporting, but favoring elected officials who are actively involved in drawing the maps—especially when they are not even nominees yet—is a dangerous precedent. It narrows the field before it opens and undercuts the deep bench of talent Democrats have worked hard to build in Virginia.

I hear Senator Lucas when she says these districts are competitive if you work them. That may be true. But optics matter. Process matters. And this approach makes it harder to argue that the door is truly open for new voices, challengers, and grassroots candidates to step forward.

At the same time, we are where we are. And we cannot afford to blow up the entire effort in pursuit of theoretical perfection. One would hope we could have produced a map that favored Democrats without undermining its own credibility—but that opportunity has passed.

So now the task is clear.

We fight like hell to win these seats. We pass the referendum. And we make sure Democrats hold and expand their congressional majority—because stopping the regressive MAGA agenda and positioning ourselves for victory in 2028 is bigger than any one map, any one district, or any one candidate.

TL;DR:

Virginia Democrats landed on a 10–1 congressional map after weeks of internal infighting. Politically, maximizing seats makes sense in a razor-thin House. Electorally, this map is a tougher sell to voters who’ve spent years being told gerrymandering is bad—and it risks undermining the referendum needed to approve it. A cleaner 9–2 map may have been more defensible. Worse, districts that appear drawn for specific individuals are shortsighted and bad optics; districts should outlast candidates and invite competition, not pre-decide outcomes. That said, we’re here now—so the job is to pass the referendum, win the seats, stop the MAGA agenda, and move toward 2028.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a