|

|

Picasso’s monumental anti-war mural uses cubism and historical tragedy to empower the public against totalitarianism and creative oppression

|

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Oil on Canvas , Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

|

Pablo Picasso lived a rich life spanning the late 19th century to the end of his life in the 1970s. Through this time, countless historical events took place, applying mountains of pressure on the very fabric of society. Artists like Picasso were influenced by this never-ending storm of chaos, enduring both world wars, and the ever-evolving technology that permeated our world. It is no wonder why Picasso's Guernica remains one of the most chilling and influential anti-war paintings in history.

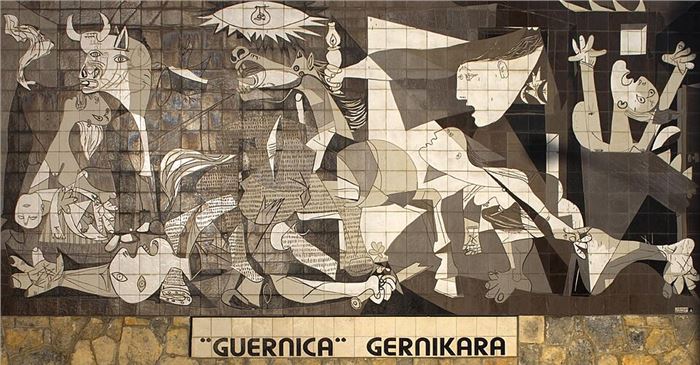

The oil painting stands over eleven feet tall and is over twenty-five feet long (roughly 3.49 meters by 7.76 meters). Unlike some of Picasso’s other well-known paintings, it is monochromatic, relying on varying grey, black, and white values. The painting’s composition is quintessential cubism, relying on geometric shapes and abstractions. While most of the canvas is filled with distorted figures there are several identifiable symbols: a sun, a lightbulb, a bull, and a horse. Guernica has been reproduced over the years, including a mural in the town of Guernica itself. The tiled wall adds much more texture to the piece than the original painted canvas. This is made apparent by the gridded lines running through the composition; the painting becomes a puzzle of assorted pieces, organizing the chaos into comprehensive segments.

A reproduction of Guernica in the form of a mural, installed for the 60th anniversary of the bombing in 1997. Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It is impossible not to speak of Guernica by just grazing the surface. The painting is rich with historical context. Guernica is the Spanish spelling of the town Guernika, a town in the province of Biscay. The community is extremely small, a slice of a principality within the Basque country (a somewhat autonomous region of Northern Spain). Guernica fell victim to a massive bombing as a result of a civil war in 1937. Air forces decimated the land, commanded by Nationalist and dictator Francisco Franco.

Pablo Picasso was in Paris when he discovered what had happened to this small town. As a man born in Spain, one can only imagine what he must have felt upon reading the news. Interestingly, this added distance had an influence on the work. One could argue that this would be a detriment; he wasn’t there when it happened, how could Picasso encapsulate the raw emotion and carnage? The painting answers that and more. The monochrome colors become not just a tone of horror and distraught, but also present the image as a historic news piece. Like a war photographer, he goes beyond reporting and deep into the dread and despair of the moment.

When asked what an artist is, Picasso famously responded:

“He is a political being, constantly aware of the heart breaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. Painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war.”

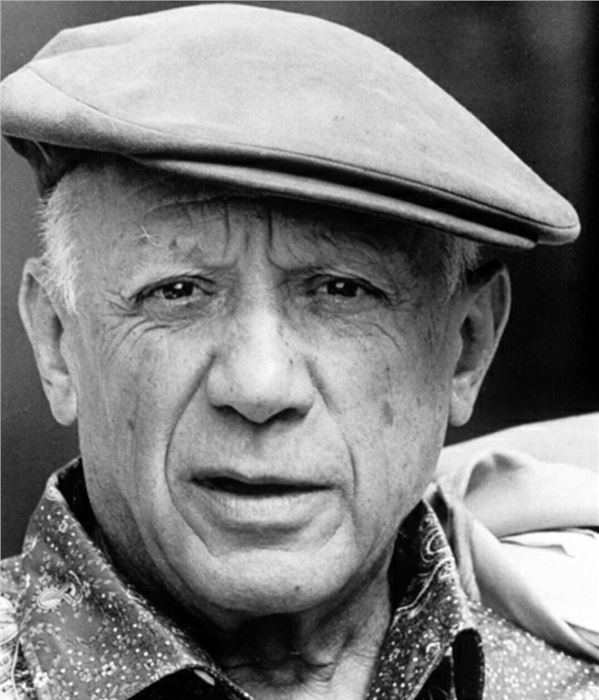

Pablo Picasso in 1962, several decades after creating Guernica. Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Guernica tells a story of spaces dismantled by chaos. Disembodied limbs are strewn across the canvas: hands, feet, arms, and even heads. One hand in particular clutches a broken blade and what appears to be a flower; the two clutched together may symbolize the capacity for peace and war in the hands of Man. This theme extends to the bull and horse, again implying that humans are certainly more animalistic than we may like to believe. The lightbulb in the sun is interesting too, as the sun could also be an eye, or perhaps a rift in the sky. Either way, there is something to be said of who watches the destruction. Perhaps it is the eye of the pilot, who dropped the bombs onto the town below. It could also be the eye of a divine creator, casting judgement on the chaos. These symbols provide plenty to reflect on, and Picasso seemed comfortable with this ambiguity.

In Picasso’s Guernica, a critical study edited by Ellen C. Opper, Picasso is quoted saying: “It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. The public who looks at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.”

When art is framed in a political setting, could this prove to be problematic? There are plenty of arguments for what the function of art should be. After all, whole political regimes have commissioned entire departments and government bodies to do just that. If abstract art is left up to interpretation, what can be said about the quality of the message that comes from it? Does it diminish its clarity?

In this case, Picasso’s Guernica balances abstraction and emotional intelligence and sentiment in the most effective way possible. The recognition is absolutely deserved, primarily because of its honesty. The entire movement of abstract art is inherently expressive and individualistic – emotive characteristics exactly opposite of what an oppressive regime expects from a nation. The world’s most deplorable historical figures, including Hitler, again and again attempted to discredit the validity of such art movements. Art movements such as Cubism, Dada, and most under the category of Modern Art were demonized, penalized, and removed from the eyes of the public. This “Degenerate Art” stood opposite to values of tradition, heroism, and domesticity, all characteristics these regimes sought after in art. Picasso was not only recollecting a horrific event in time, but also used this massive mural as a platform to support modern expressionism and an art movement dedicated to freedom and creative thought.

The power of Guernica does not come from initial glances. It takes time to sit with, and a moment of independent reflection to fully grasp. In this fast-paced world, it is easy to look at things too quickly. Generalizations are made, headlines are quick and catchy, but it is very rare that a person gets to sit and reflect on a story for more than a few minutes or so. Picasso’s work demands introspection, and through such asks, the audience grows better for it. This doesn’t just increase the value of Picasso’s work, but also strives to empower the public with personal knowledge, media literacy, and an attention to detail. All of these things make Guernica and pieces like it a shield against totalitarianism and nonindependent thought.

Audience viewing Guernica at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, Spain. The museum is known for its collection of Pablo Picasso’s works and other 20th-century Spanish Art. Photo by Pedro Belleza, found on Wikimedia Commons

The world is becoming more and more volatile as the years go on. Thus, it is extremely important to allow history to better prepare us for our future. It is easy to stomach what is nice to look at, or what is comfortable, but that complacency can prove dangerous. Guernica is just as much a reminder of past horrors, as it is a warning to never let something like this happen again.

|

|

|