|

|

John —

I was moving some boxes of old stuff into the attic recently and found a couple of scrapbooks. One of them included a photo from high school that I just had to share with you.

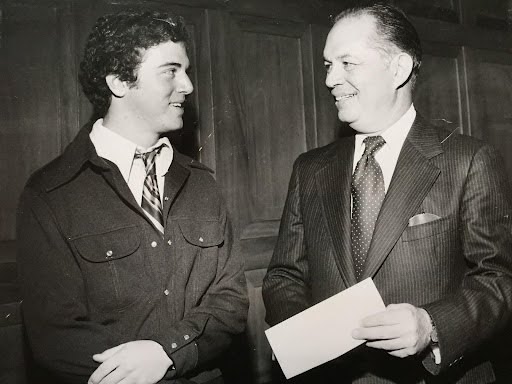

This photo is of me after winning a competition for a speech on America’s free enterprise system, believe it or not. (Leave it to a high school student whose only relevant experience was working in a restaurant and his father’s lumber yard to opine on the economy.) The envelope contained a check for first prize — it was a hundred dollars. That was a lot of money back then. It still is. Just take a look:

When I was 11 years old, my dad moved our family from Scottsdale, Arizona, to the San Francisco Bay Area. I started in a new middle school before attending Monte Vista High School in Danville.

I played on the soccer team and had several wonderful teachers who really made a mark on me. There was Mr. Morrison, who taught contemporary world problems; Ms. Shackleford, my calculus teacher; and the other Mr. Morrison, who taught physiology and had us dissecting fetal pigs — I can still smell the formaldehyde. Ugh.

But the two teachers who left the biggest mark on me were Ms. Abbott, my Shakespeare teacher, and Al Gentile, my speech coach.

Ms. Abbott took our class up to Ashland, Oregon, each summer for the Shakespeare festival, but it was Mr. Gentile who taught us the art of public speaking. That was the after-school activity that really got me going, and I was soon competing in speech tournaments. At first, I wasn’t very good, scoring 5s at tournaments, which was, well, the lowest score you could get. I did dramatic interpretation — Twelve Angry Men and Inherit the Wind were a couple of favorites — I loved those plays, but … they didn’t love me.

Then I switched to Original Oratory, and things started to change. In “OO,” you could write your own material, craft a speech on a topic of your own choice, and that made all the difference. Hence, the picture before you now.

Although speaking before others did not come naturally to me, I worked hard at it, reading great speeches from Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, and listening to recordings of Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, and more.

I couldn’t get enough. From the tinny phonograph in my bedroom came these wonderful, if scratchy, recordings of the greatest speakers of the modern era. It was mesmerizing. And from my brother’s room next door, the sounds of Richard Burton, Laurence Olivier, and other greats performing Shakespeare.

To this day, I draw on those voices and those speeches for inspiration when I’m writing a speech. For my core thesis, I gather the elements that I want to weave together from history, the law or Constitution, or, in the case of an investigation, the key pieces of evidence.

Perhaps most importantly, I try to outline the speech I want to give in my head, without the tyranny of a blank page in front of me. Only when I have a good idea of how I want to structure the piece do I sit down to write. Ideally, in a comfy chair by the fire.

During the first impeachment trial of President Trump, I would take notes on the key elements that I thought should be incorporated into a closing argument for the day. If I didn’t have time to write the closing, I would put numbers next to each of those bullets to put them in some logical order that told a story. And then I would improvise.

But occasionally, I had a whole evening to write a closing argument, and there, I waited until my thoughts coalesced around the theme and its most logical order before putting pen to paper, or more accurately, fingers to iPad!

Now that I’m in the Senate, and Trump is back in office, I am once again drawing on history, the law, and the Constitution to respond to the actions of this administration from the Senate floor or speaking to constituents in town halls.

Some things never change. But the lessons from those early years — and from those teachers — have stayed with me:

The need to speak plainly, but not dumb down your words. The need to communicate in a way that draws on the inherent beauty of our language and our higher aspirations and ideals. And the need to appeal to the best in human nature, not the worst. There is unlimited power in words — good and bad — and I never forget that.

I hope these lessons have helped me be a more effective advocate for our democracy. My parents and teachers taught me that certain very basic values really mattered. That truth matters, that decency matters, and that our democracy matters. And it’s up to each one of us to use the skills we have to fight for them.

And it’s why I’m asking you today:

If you've saved your payment information with ActBlue Express, your donation will go through immediately:

It’s up to each of us to fight for what we believe in and for our democracy, however best we can. And I want to thank you for being a part of that fight.

Thanks,

Adam

|