Email

The best news you’ll read all weekend

| From | Shahid Buttar <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The best news you’ll read all weekend |

| Date | November 30, 2025 7:55 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

When I moved to the mountains in 2022, I found myself excited by many things, including a summer job guiding kayak tours on Lake Tahoe. My tours emphasize ecology and history, and wanting to offer more depth for my guests led me to explore a local history by which I’ve been continually fascinated.

At our company’s annual post-season dinner, I recently learned that my colleagues named me our “most knowledgeable” and “most inspiring” tour guide. As I told them in the speech they demanded, “If America had learned anything from the devastation it wrought in this particular place, your futures would suck a lot less.”

Thanks for reading Chronicles of a Dying Empire! You can help inform—and inspire—your friends by sharing this post.

Original people

The first human settlements in the area where I now live were those of the Washoe people [ [link removed] ], whose ancestral lands overlapped those of their sister tribe to the north, the Paiute [ [link removed] ]. The Paiute range across Nevada and into Utah, while the Washoe have a smaller range straddling what is now the border between Nevada and California.

The Washoe were historically a nomadic people, migrating frequently in order to maximize their access to seasonally available food resources. In the winter time, they lived in the valleys in western Nevada, where lower elevation and higher temperatures allowed more abundant resources than the Sierra Nevada (literally, “snowy mountains” in Spanish) to the west. They usually trekked into the mountains surrounding Lake Tahoe during the summer, when food is more plentiful.

Evidence of Washoe settlement is apparent around the entire Lake Tahoe basin: there are indentations in rocks [ [link removed] ]—reflecting sites where pine nuts and acorns were ground into flour—at the tops of every mountain peak, and even on rocks across the lake itself.

These indigenous communities peacefully coexisted with the land for thousands of years until Lake Tahoe’s “discovery” by settler-colonists in 1844.

Chronicles of a Dying Empire is a publication made possible by readers. To receive new posts, sign up for a free subscription! Paid subscribers help support my work and make it available for 21,000 readers to learn for free.

Stolen land

Within a single generation, whatever passes for western civilization wreaked havoc on the landscape. Coinciding with the onset of industrialization, the exploration of the lake Tahoe region started off slowly for a few years, until the discovery of Gold at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 sparked a global mass migration that escalated dramatically within a year.

This is the era that established [ [link removed] ] San Francisco. It grew from a Spanish Mission settlement with under 1,000 people in 1847 to, within a year of the gold strike, 25,000 by 1849. Long before the city became a hub for technology, LGBTQ culture, and a tragically ignorant [ [link removed] ] version of white supremacy [ [link removed] ] that continues [ [link removed] ] to infect it today, it was a mining colony, a destination for sea-borne prospectors whose ultimate destination was the mountains to the east.

The first phase of the Gold Rush sparked the indigenous genocide [ [link removed] ] that besieged California long after the massacres on the East Coast ironically celebrated this weekend. As I frequently remind guests on my kayak tours, the genocide in the east was relatively more brutal—but despite the contemporary “progressive” reputation enjoyed by California, its crimes [ [link removed] ] against humanity were far more recent.

The ecocide started ten years after the Gold Rush, with the discovery of silver in 1859 on the other side of the Washoe’s ancestral range, in what would soon become Nevada. I’ll save the history for how Tahoe’s natural resources helped liberate a race of enslaved Americans for another post, but would note for now that—in one of the first examples of industrial resource extraction ever on Earth—100 million trees were mowed to the ground [ [link removed] ] within a generation of the lake’s discovery by white settlers moving west.

The resulting genocide and ecocide could have offered warnings for a civilization insightful enough to learn its lessons. Alas, we are not part of one.

Enabled by the ignorance of the impacts of that era, industrial civilization went on to wreck not only local ecosystems, but also the entire biosphere. We today live in the shadow [ [link removed] ] of a future poisoned [ [link removed] ] by accelerating climate catastrophes.

It did not have to be this way.

If a younger America had been willing to respect indigenous rights, all of our futures today would be immeasurably brighter.

Land back

In this context, it is especially important for indigenous communities to receive their land back—not only for them, but for all of us and the future we share.

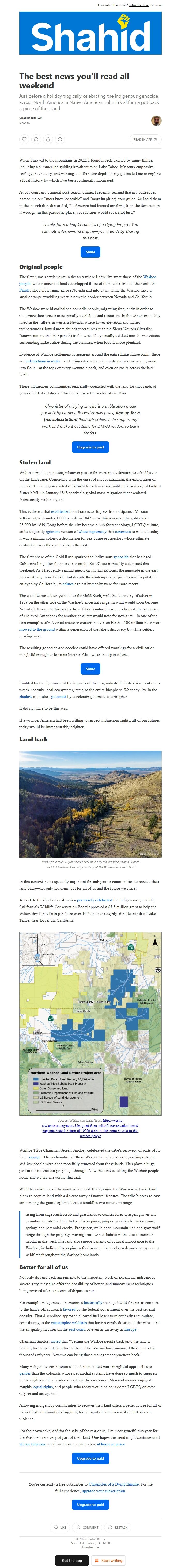

A week to the day before America perversely celebrated [ [link removed] ] the indigenous genocide, California’s Wildlife Conservation Board approved a $5.5 million grant to help the Wášiw-šiw Land Trust purchase over 10,250 acres roughly 50 miles north of Lake Tahoe, near Loyalton, California.

Washoe Tribe Chairman Serrell Smokey celebrated the tribe’s recovery of parts of its land, saying [ [link removed] ], “The reclamation of these Washoe homelands is of great importance. Wá·šiw people were once forcefully removed from these lands. This plays a huge part in the trauma our people go through. Now the land is calling the Washoe people home and we are answering that call.”

With the assistance of the grant announced 10 days ago, the Wášiw-šiw Land Trust plans to acquire land with a diverse array of natural features. The tribe’s press release announcing the grant explained that it straddles two mountain ranges:

rising from sagebrush scrub and grasslands to conifer forests, aspen groves and mountain meadows. It includes pinyon pines, juniper woodlands, rocky crags, springs and perennial creeks. Pronghorn, mule deer, mountain lion and gray wolf range through the property, moving from winter habitat in the east to summer habitat in the west. The land also supports plants of cultural importance to the Washoe, including pinyon pine, a food source that has been devastated by recent wildfires throughout the Washoe homelands.

Better for all of us

Not only do land back agreements to the important work of expanding indigenous sovereignty, they also offer the possibility of better land management techniques being revived after centuries of dispossession.

For example, indigenous communities historically [ [link removed] ] managed wild forests, in contrast to the hands-off approach favored [ [link removed] ] by the federal government over the past several decades. That discredited approach allowed fuel loads to relentlessly accumulate, contributing to the catastrophic wildfires [ [link removed] ] that have recently devastated the west—and the air quality in cities on the east coast [ [link removed] ], or even as far away as Europe [ [link removed] ].

Chairman Smokey noted [ [link removed] ] that “Getting the Washoe people back onto the land is healing for the people and for the land. The Wá·šiw have managed these lands for thousands of years. Now we can bring those management practices back.”

Many indigenous communities also demonstrated more insightful approaches to gender [ [link removed] ] than the colonists whose patriarchal systems have done so much to suppress human rights in the decades since their dispossession. Men and women enjoyed roughly equal rights [ [link removed] ], and people who today would be considered LGBTQ enjoyed respect and acceptance.

Allowing indigenous communities to recover their land offers a better future for all of us, not just communities struggling for recognition after years of relentless state violence.

For their own sake, and for the sake of the rest of us, I’m most grateful this year for the Washoe’s recovery of part of their land. One hopes the trend might continue until all our relations [ [link removed] ] are allowed once again to live at home in peace [ [link removed] ].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

When I moved to the mountains in 2022, I found myself excited by many things, including a summer job guiding kayak tours on Lake Tahoe. My tours emphasize ecology and history, and wanting to offer more depth for my guests led me to explore a local history by which I’ve been continually fascinated.

At our company’s annual post-season dinner, I recently learned that my colleagues named me our “most knowledgeable” and “most inspiring” tour guide. As I told them in the speech they demanded, “If America had learned anything from the devastation it wrought in this particular place, your futures would suck a lot less.”

Thanks for reading Chronicles of a Dying Empire! You can help inform—and inspire—your friends by sharing this post.

Original people

The first human settlements in the area where I now live were those of the Washoe people [ [link removed] ], whose ancestral lands overlapped those of their sister tribe to the north, the Paiute [ [link removed] ]. The Paiute range across Nevada and into Utah, while the Washoe have a smaller range straddling what is now the border between Nevada and California.

The Washoe were historically a nomadic people, migrating frequently in order to maximize their access to seasonally available food resources. In the winter time, they lived in the valleys in western Nevada, where lower elevation and higher temperatures allowed more abundant resources than the Sierra Nevada (literally, “snowy mountains” in Spanish) to the west. They usually trekked into the mountains surrounding Lake Tahoe during the summer, when food is more plentiful.

Evidence of Washoe settlement is apparent around the entire Lake Tahoe basin: there are indentations in rocks [ [link removed] ]—reflecting sites where pine nuts and acorns were ground into flour—at the tops of every mountain peak, and even on rocks across the lake itself.

These indigenous communities peacefully coexisted with the land for thousands of years until Lake Tahoe’s “discovery” by settler-colonists in 1844.

Chronicles of a Dying Empire is a publication made possible by readers. To receive new posts, sign up for a free subscription! Paid subscribers help support my work and make it available for 21,000 readers to learn for free.

Stolen land

Within a single generation, whatever passes for western civilization wreaked havoc on the landscape. Coinciding with the onset of industrialization, the exploration of the lake Tahoe region started off slowly for a few years, until the discovery of Gold at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 sparked a global mass migration that escalated dramatically within a year.

This is the era that established [ [link removed] ] San Francisco. It grew from a Spanish Mission settlement with under 1,000 people in 1847 to, within a year of the gold strike, 25,000 by 1849. Long before the city became a hub for technology, LGBTQ culture, and a tragically ignorant [ [link removed] ] version of white supremacy [ [link removed] ] that continues [ [link removed] ] to infect it today, it was a mining colony, a destination for sea-borne prospectors whose ultimate destination was the mountains to the east.

The first phase of the Gold Rush sparked the indigenous genocide [ [link removed] ] that besieged California long after the massacres on the East Coast ironically celebrated this weekend. As I frequently remind guests on my kayak tours, the genocide in the east was relatively more brutal—but despite the contemporary “progressive” reputation enjoyed by California, its crimes [ [link removed] ] against humanity were far more recent.

The ecocide started ten years after the Gold Rush, with the discovery of silver in 1859 on the other side of the Washoe’s ancestral range, in what would soon become Nevada. I’ll save the history for how Tahoe’s natural resources helped liberate a race of enslaved Americans for another post, but would note for now that—in one of the first examples of industrial resource extraction ever on Earth—100 million trees were mowed to the ground [ [link removed] ] within a generation of the lake’s discovery by white settlers moving west.

The resulting genocide and ecocide could have offered warnings for a civilization insightful enough to learn its lessons. Alas, we are not part of one.

Enabled by the ignorance of the impacts of that era, industrial civilization went on to wreck not only local ecosystems, but also the entire biosphere. We today live in the shadow [ [link removed] ] of a future poisoned [ [link removed] ] by accelerating climate catastrophes.

It did not have to be this way.

If a younger America had been willing to respect indigenous rights, all of our futures today would be immeasurably brighter.

Land back

In this context, it is especially important for indigenous communities to receive their land back—not only for them, but for all of us and the future we share.

A week to the day before America perversely celebrated [ [link removed] ] the indigenous genocide, California’s Wildlife Conservation Board approved a $5.5 million grant to help the Wášiw-šiw Land Trust purchase over 10,250 acres roughly 50 miles north of Lake Tahoe, near Loyalton, California.

Washoe Tribe Chairman Serrell Smokey celebrated the tribe’s recovery of parts of its land, saying [ [link removed] ], “The reclamation of these Washoe homelands is of great importance. Wá·šiw people were once forcefully removed from these lands. This plays a huge part in the trauma our people go through. Now the land is calling the Washoe people home and we are answering that call.”

With the assistance of the grant announced 10 days ago, the Wášiw-šiw Land Trust plans to acquire land with a diverse array of natural features. The tribe’s press release announcing the grant explained that it straddles two mountain ranges:

rising from sagebrush scrub and grasslands to conifer forests, aspen groves and mountain meadows. It includes pinyon pines, juniper woodlands, rocky crags, springs and perennial creeks. Pronghorn, mule deer, mountain lion and gray wolf range through the property, moving from winter habitat in the east to summer habitat in the west. The land also supports plants of cultural importance to the Washoe, including pinyon pine, a food source that has been devastated by recent wildfires throughout the Washoe homelands.

Better for all of us

Not only do land back agreements to the important work of expanding indigenous sovereignty, they also offer the possibility of better land management techniques being revived after centuries of dispossession.

For example, indigenous communities historically [ [link removed] ] managed wild forests, in contrast to the hands-off approach favored [ [link removed] ] by the federal government over the past several decades. That discredited approach allowed fuel loads to relentlessly accumulate, contributing to the catastrophic wildfires [ [link removed] ] that have recently devastated the west—and the air quality in cities on the east coast [ [link removed] ], or even as far away as Europe [ [link removed] ].

Chairman Smokey noted [ [link removed] ] that “Getting the Washoe people back onto the land is healing for the people and for the land. The Wá·šiw have managed these lands for thousands of years. Now we can bring those management practices back.”

Many indigenous communities also demonstrated more insightful approaches to gender [ [link removed] ] than the colonists whose patriarchal systems have done so much to suppress human rights in the decades since their dispossession. Men and women enjoyed roughly equal rights [ [link removed] ], and people who today would be considered LGBTQ enjoyed respect and acceptance.

Allowing indigenous communities to recover their land offers a better future for all of us, not just communities struggling for recognition after years of relentless state violence.

For their own sake, and for the sake of the rest of us, I’m most grateful this year for the Washoe’s recovery of part of their land. One hopes the trend might continue until all our relations [ [link removed] ] are allowed once again to live at home in peace [ [link removed] ].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a