What Works?: America's New No-Nonsense Realism

by Pierre Rehov • November 19, 2025 at 5:00 am

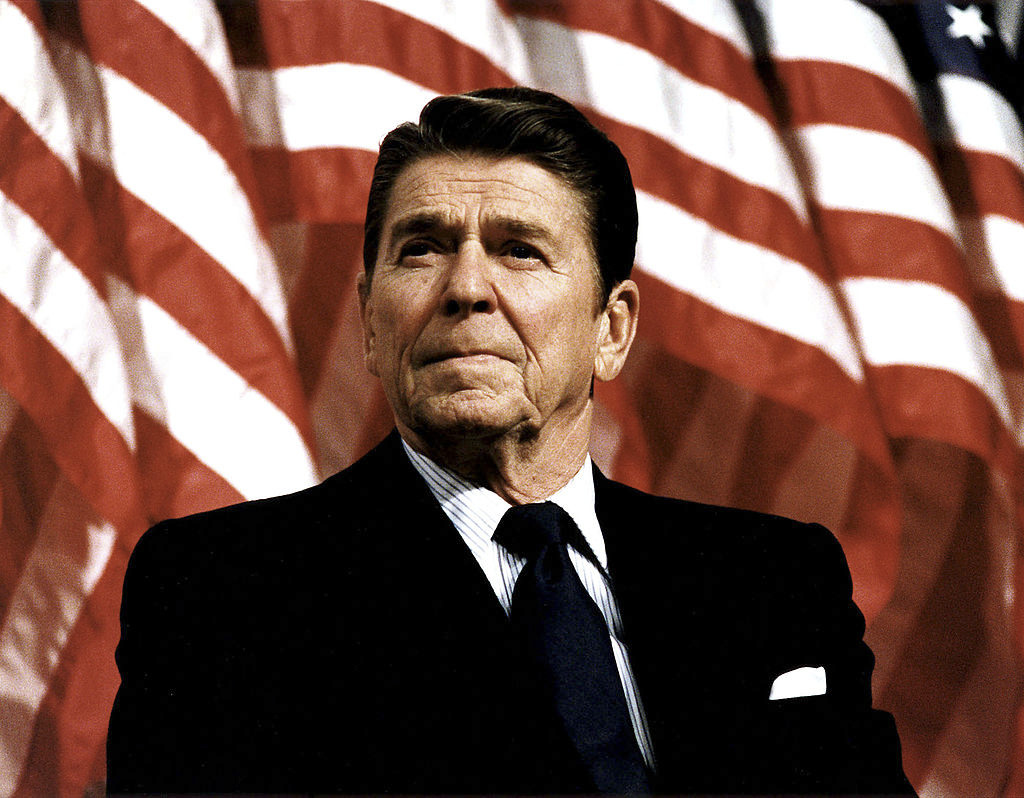

This new statecraft, begun by [US President Ronald] Reagan, was neither isolationist nor utopian. It was positive and pragmatic, based on whatever might work, rather than confined by ideological strictures. Its successes—such as revitalized growth, a revived military and renewed national morale—have given the US a strategic steadiness.

Both political parties, once fluent in kitchen‑table economics and national pride, often sounded like seminars rather than delivering positive results, for instance a functional education for its citizens, or "affordable healthcare" that was actually affordable.

Into this vacuum came a businessman, speaking a language voters understood: borders, jobs, sovereignty, and global respect. He did not reject American leadership; he redefined it as the capacity to secure the interests of American citizens. Tariffs – which other countries had been imposing on the US – were not "taxes" or theology; they were instruments of geopolitical persuasion other than war. Alliances were tools to strengthen America's military breadth. Diplomacy was to be measured by outcomes—defeated terrorists, deterred adversaries, reshored industries—not by applause at international conferences.

On China, the government's new hard look at reality ended decades of wishful thinking that economic engagement alone would liberalize a Leninist party‑state. By imposing tariffs and spotlighting technology theft, supply‑chain vulnerabilities, and the national‑security stakes of having handed over American jobs to its adversaries, he forced a reconsideration of how much malign behavior it is advisable to tolerate.

Communist China, in 1990, had already declared a "Peoples War" – meaning all-out war – on the US.

On the Middle East, the government rediscovered deterrence making it clear -- credibly -- to enemies that the cost to them of aggression would be catastrophically high.

Looking at "what works" demands that leaders match means to ends and judge policies by what they deliver. Under this lens, moral posturing is not a virtue; it is vanity. A nation that promises to save the world while failing to protect its own communities is not moral—it is at best negligent, at worst catastrophically destructive, as can be seen in much of Europe.

What looks like the "moral righteousness" often compounds the problem: it depends on who thinks what is "moral." Many seem to have recast foreign policy as "virtue signaling": proclamations (here, here and here), hashtags, and ambitious frameworks that unravel upon contact with reality. Multilateral consensus, as over "climate change," is confused with legitimacy and national borders are treated as embarrassments rather than as obligations to protect one's citizens. for national security. This is not compassion; again, it is vanity -- abdication cloaked as empathy.

Pragmatic, unsentimental realism is not cynical: it assumes that safeguarding a nation requires enforceable borders, credible deterrence, and increasing paychecks.

While an unsecured border may sound humane; it is often seen as an invitation for abuse. America's current call for enforcement—walls, technology, remain‑in‑Mexico, interior checks — should be judged by results: fewer deaths, less fentanyl, safer streets.

The United States faces simultaneous challenges from China's aggression, Russia's expansion, and Iran's terror networks. The United States cannot meet them with "slogans." It needs steady, vast, defense spending; energy dominance – most urgently from developing nuclear fusion energy with which China is racing ahead, rather than US addiction to low-hanging nuclear, fission energy.

Some politicians, perversely, seem to obstruct their constituents from flourishing – perhaps to keep them dependent on promises always just a nose in front of them; perhaps to thwart accomplishments by another political party to prevent one's own deficiencies from being exposed. The antidote is the Constitution —checks and balances, federalism that gives power to the states, and public debate that keeps leaders tethered to positive results.

When US President Ronald Reagan revived the phrase "shining city on a hill," he did so not as a marketing flourish but as a governing ethic: the United States would deter evil by projecting confidence, prosperity and moral clarity.

His message blended optimism with hard power — lower taxes and deregulation to spur growth, rebuilding the military to restore deterrence, and an unapologetic defense of Western civilization. The mix resonated because it tied virtue to results: fewer hostages, a stronger dollar, and an adversary in Moscow forced onto its back foot. This fusion of ideals and outcomes gave the GOP a compass that pointed true north.