Email

NHS waiting lists: why it’s even worse than it looks

| From | Institute of Economic Affairs <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NHS waiting lists: why it’s even worse than it looks |

| Date | November 18, 2025 8:01 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

By Nick White, Medical Director and Consultant Surgeon

Last year, Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Health Secretary Wes Streeting took office on a platform of reducing NHS waiting lists, pledging an extra 2 million operations, scans and appointments, as well as doubling the amount of cancer scanners. The promise to “cut NHS waiting times” was again repeated in last year’s King’s speech.

There are three key metrics used to look at NHS waiting times. They are the 18-week elective pathway, the 62-day cancer pathway and the 4-hour emergency department wait.

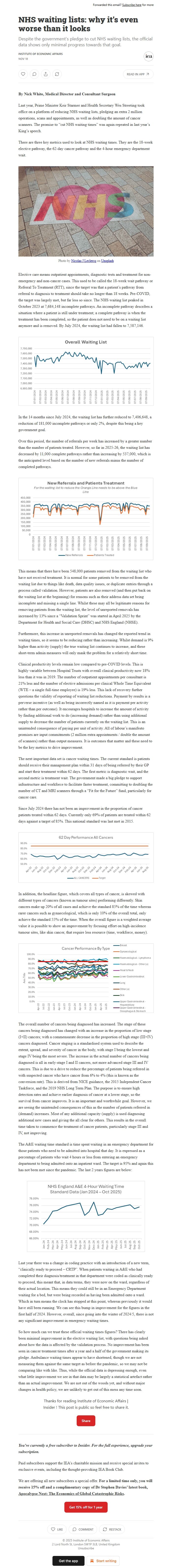

Elective care means outpatient appointments, diagnostic tests and treatment for non-emergency and non-cancer cases. This used to be called the 18-week wait pathway or Referral To Treatment (RTT), since the target was that a patient’s pathway from referral to diagnosis to treatment should take no longer than 18 weeks. Pre-COVID, the target was largely met, but far less so since. The NHS waiting list peaked in October 2023 at 7,684,148 incomplete pathways. An incomplete pathway describes a situation where a patient is still under treatment; a complete pathway is when the treatment has been completed, so the patient does not need to be on a waiting list anymore and is removed. By July 2024, the waiting list had fallen to 7,587,146.

In the 14 months since July 2024, the waiting list has further reduced to 7,406,648, a reduction of 181,000 incomplete pathways or only 2%, despite this being a key government goal.

Over this period, the number of referrals per week has increased by a greater number than the number of patients treated. However, so far in 2025-26, the waiting list has decreased by 11,000 complete pathways rather than increasing by 537,000, which is the anticipated level based on the number of new referrals minus the number of completed pathways.

This means that there have been 548,000 patients removed from the waiting list who have not received treatment. It is normal for some patients to be removed from the waiting list due to things like death, data quality issues, or duplicate entries through a process called validation. However, patients are also removed (and then put back on the waiting list at the beginning) for reasons such as their address data set being incomplete and missing a single line. Whilst these may all be legitimate reasons for removing patients from the waiting list, the level of unreported removals has increased by 13% since a “Validation Sprint” was started in April 2025 by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and NHS England (NHSE).

Furthermore, this increase in unreported removals has changed the reported trend in waiting times, so it seems to be reducing rather than increasing. Whilst demand is 9% higher than activity (supply) the true waiting list continues to increase, and these short-term admin measures will only mask the problem for a relatively short time.

Clinical productivity levels remain low compared to pre-COVID levels. This is highly variable between Hospital Trusts with overall clinical productivity now 18% less than it was in 2019. The number of outpatient appointments per consultant is 21% less and the number of elective admissions per clinical Whole Time Equivalent (WTE – a single full-time employee) is 19% less. This lack of recovery further questions the validity of reporting of waiting list reductions. Payment by results is a perverse incentive (as well as being incorrectly named as it is payment per activity rather than per outcome). It encourages hospitals to increase the amount of activity by finding additional work to do (increasing demand) rather than using additional supply to decrease the number of patients currently on the waiting list. This is an unintended consequence of paying per unit of activity. All of labour’s manifesto promises are input commitments (2 million extra appointments / double the amount of scanners) rather than output measures. It is outcomes that matter and these need to be the key metrics to drive improvement.

The next important data set is cancer waiting times. The current standard is patients should receive their management plan within 31 days of being referred by their GP and start their treatment within 62 days. The first metric is diagnostic wait, and the second metric is treatment wait. The government made a big pledge to support infrastructure and workforce to facilitate faster treatment, committing to doubling the number of CT and MRI scanners through a “Fit for the Future” fund, particularly for cancer care.

Since July 2024 there has not been an improvement in the proportion of cancer patients treated within 62 days. Currently only 69% of patients are treated within 62 days against a target of 85%. This national standard was last met in 2015.

In addition, the headline figure, which covers all types of cancer, is skewed with different types of cancers (known as tumour sites) performing differently. Skin cancers make up 20% of all cases and achieve the standard 85% of the time whereas rarer cancers such as gynaecological, which is only 10% of the overall total, only achieve the standard 55% of the time. When the overall figure is a weighted average value it is possible to show an improvement by focusing effort on high-incidence tumour sites, like skin cancer, that require less resource (time, workforce, money).

The overall number of cancers being diagnosed has increased. The stage of these cancers being diagnosed has changed with an increase in the proportion of low stage (I+II) cancers; with a commensurate decrease in the proportion of high stage (III+IV) cancers diagnosed. Cancer staging is a standardised system used to describe the extent, spread, and severity of cancer in the body, with stage I being the lowest and stage IV being the most severe. The increase in the actual number of cancers being diagnosed is all in early-stage I and II cancers, not more advanced stage III and IV cancers. This is due to a drive to reduce the percentage of patients being referred in with suspected cancer who have cancer from 6% to 4% (this is known as the conversion rate). This is derived from NICE guidance, the 2015 Independent Cancer Taskforce, and the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan. The purpose is to ensure high detection rates and achieve earlier diagnosis of cancer at a lower stage, so the survival from cancer improves. It is an important and worthwhile goal. However, we are seeing the unintended consequences of this as the number of patients referred in (demand) increases. Most of any additional capacity (supply) is used diagnosing additional new cases and giving the all clear for others. This results in the overall time taken to commence the treatment of cancer patients, particularly stage III and IV, not improving.

The A&E waiting time standard is time spent waiting in an emergency department for those patients who need to be admitted into hospital that day. It is expressed as a percentage of patients who wait 4 hours or less from entering an emergency department to being admitted onto an inpatient ward. The target is 95% and again this has not been met since the pandemic. The last 2 years figures are below:

Last year there was a change in coding practice with an introduction of a new term, “clinically ready to proceed – CRTP”. When patients waiting in A&E who had completed their diagnosis/treatment in that department were coded as clinically ready to proceed, this meant that, in data terms, they were now on the ward, regardless of their actual location. This means they could still be in an Emergency Department waiting for a bed, but were being recorded as having been admitted onto a ward. Which in turn means the clock has stopped at this point, whereas previously it would have still been running. We can see this bump in improvement for the figures in the first half of 2024. However, overall, since going into the winter of 2024/5, there is not any significant improvement in emergency waiting times.

So how much can we trust these official waiting times figures? There has clearly been minimal improvement in the elective waiting list, with questions being asked about how the data is affected by the validation process. No improvement has been seen in cancer treatment times after a year and a half of the government making its pledge. Ambulance waiting times appear to have shortened, though we are not measuring them against the same target as before the pandemic, so we may not be comparing like with like. Thus, while the official data is depressing enough, even what little improvement we see in that data may be largely a statistical artefact rather than an actual improvement. We are not out of the woods yet, and without major changes in health policy, we are unlikely to get out of this mess any time soon.

Thanks for reading Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider ! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

By Nick White, Medical Director and Consultant Surgeon

Last year, Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Health Secretary Wes Streeting took office on a platform of reducing NHS waiting lists, pledging an extra 2 million operations, scans and appointments, as well as doubling the amount of cancer scanners. The promise to “cut NHS waiting times” was again repeated in last year’s King’s speech.

There are three key metrics used to look at NHS waiting times. They are the 18-week elective pathway, the 62-day cancer pathway and the 4-hour emergency department wait.

Elective care means outpatient appointments, diagnostic tests and treatment for non-emergency and non-cancer cases. This used to be called the 18-week wait pathway or Referral To Treatment (RTT), since the target was that a patient’s pathway from referral to diagnosis to treatment should take no longer than 18 weeks. Pre-COVID, the target was largely met, but far less so since. The NHS waiting list peaked in October 2023 at 7,684,148 incomplete pathways. An incomplete pathway describes a situation where a patient is still under treatment; a complete pathway is when the treatment has been completed, so the patient does not need to be on a waiting list anymore and is removed. By July 2024, the waiting list had fallen to 7,587,146.

In the 14 months since July 2024, the waiting list has further reduced to 7,406,648, a reduction of 181,000 incomplete pathways or only 2%, despite this being a key government goal.

Over this period, the number of referrals per week has increased by a greater number than the number of patients treated. However, so far in 2025-26, the waiting list has decreased by 11,000 complete pathways rather than increasing by 537,000, which is the anticipated level based on the number of new referrals minus the number of completed pathways.

This means that there have been 548,000 patients removed from the waiting list who have not received treatment. It is normal for some patients to be removed from the waiting list due to things like death, data quality issues, or duplicate entries through a process called validation. However, patients are also removed (and then put back on the waiting list at the beginning) for reasons such as their address data set being incomplete and missing a single line. Whilst these may all be legitimate reasons for removing patients from the waiting list, the level of unreported removals has increased by 13% since a “Validation Sprint” was started in April 2025 by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and NHS England (NHSE).

Furthermore, this increase in unreported removals has changed the reported trend in waiting times, so it seems to be reducing rather than increasing. Whilst demand is 9% higher than activity (supply) the true waiting list continues to increase, and these short-term admin measures will only mask the problem for a relatively short time.

Clinical productivity levels remain low compared to pre-COVID levels. This is highly variable between Hospital Trusts with overall clinical productivity now 18% less than it was in 2019. The number of outpatient appointments per consultant is 21% less and the number of elective admissions per clinical Whole Time Equivalent (WTE – a single full-time employee) is 19% less. This lack of recovery further questions the validity of reporting of waiting list reductions. Payment by results is a perverse incentive (as well as being incorrectly named as it is payment per activity rather than per outcome). It encourages hospitals to increase the amount of activity by finding additional work to do (increasing demand) rather than using additional supply to decrease the number of patients currently on the waiting list. This is an unintended consequence of paying per unit of activity. All of labour’s manifesto promises are input commitments (2 million extra appointments / double the amount of scanners) rather than output measures. It is outcomes that matter and these need to be the key metrics to drive improvement.

The next important data set is cancer waiting times. The current standard is patients should receive their management plan within 31 days of being referred by their GP and start their treatment within 62 days. The first metric is diagnostic wait, and the second metric is treatment wait. The government made a big pledge to support infrastructure and workforce to facilitate faster treatment, committing to doubling the number of CT and MRI scanners through a “Fit for the Future” fund, particularly for cancer care.

Since July 2024 there has not been an improvement in the proportion of cancer patients treated within 62 days. Currently only 69% of patients are treated within 62 days against a target of 85%. This national standard was last met in 2015.

In addition, the headline figure, which covers all types of cancer, is skewed with different types of cancers (known as tumour sites) performing differently. Skin cancers make up 20% of all cases and achieve the standard 85% of the time whereas rarer cancers such as gynaecological, which is only 10% of the overall total, only achieve the standard 55% of the time. When the overall figure is a weighted average value it is possible to show an improvement by focusing effort on high-incidence tumour sites, like skin cancer, that require less resource (time, workforce, money).

The overall number of cancers being diagnosed has increased. The stage of these cancers being diagnosed has changed with an increase in the proportion of low stage (I+II) cancers; with a commensurate decrease in the proportion of high stage (III+IV) cancers diagnosed. Cancer staging is a standardised system used to describe the extent, spread, and severity of cancer in the body, with stage I being the lowest and stage IV being the most severe. The increase in the actual number of cancers being diagnosed is all in early-stage I and II cancers, not more advanced stage III and IV cancers. This is due to a drive to reduce the percentage of patients being referred in with suspected cancer who have cancer from 6% to 4% (this is known as the conversion rate). This is derived from NICE guidance, the 2015 Independent Cancer Taskforce, and the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan. The purpose is to ensure high detection rates and achieve earlier diagnosis of cancer at a lower stage, so the survival from cancer improves. It is an important and worthwhile goal. However, we are seeing the unintended consequences of this as the number of patients referred in (demand) increases. Most of any additional capacity (supply) is used diagnosing additional new cases and giving the all clear for others. This results in the overall time taken to commence the treatment of cancer patients, particularly stage III and IV, not improving.

The A&E waiting time standard is time spent waiting in an emergency department for those patients who need to be admitted into hospital that day. It is expressed as a percentage of patients who wait 4 hours or less from entering an emergency department to being admitted onto an inpatient ward. The target is 95% and again this has not been met since the pandemic. The last 2 years figures are below:

Last year there was a change in coding practice with an introduction of a new term, “clinically ready to proceed – CRTP”. When patients waiting in A&E who had completed their diagnosis/treatment in that department were coded as clinically ready to proceed, this meant that, in data terms, they were now on the ward, regardless of their actual location. This means they could still be in an Emergency Department waiting for a bed, but were being recorded as having been admitted onto a ward. Which in turn means the clock has stopped at this point, whereas previously it would have still been running. We can see this bump in improvement for the figures in the first half of 2024. However, overall, since going into the winter of 2024/5, there is not any significant improvement in emergency waiting times.

So how much can we trust these official waiting times figures? There has clearly been minimal improvement in the elective waiting list, with questions being asked about how the data is affected by the validation process. No improvement has been seen in cancer treatment times after a year and a half of the government making its pledge. Ambulance waiting times appear to have shortened, though we are not measuring them against the same target as before the pandemic, so we may not be comparing like with like. Thus, while the official data is depressing enough, even what little improvement we see in that data may be largely a statistical artefact rather than an actual improvement. We are not out of the woods yet, and without major changes in health policy, we are unlikely to get out of this mess any time soon.

Thanks for reading Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider ! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a