|

by David Starkie

|

Property taxes are flavour of the month in the lead-up to the Chancellor’s late November budget with much discussion taking place of how a change in the way property is taxed could make a significant contribution to the budgetary black hole Ms Reeves is aiming to fix to get Britain growing again. Although a popular solution on the left of politics, taxing property, specifically land, has significant support from economic theorists (it is seen potentially as a tax on economic rent minimising distortionary effects on the wider economy) and has a distinctive historical pedegree. William of Normandy on conquering England in 1066 instructed data to be gathered, the Doomsday survey, in order to impose taxes on landed property.

Today in the UK there are several taxes on residential property, notably on capital gains from the sale of second homes, a stamp duty transaction tax on home purchase, and local council taxes. There are also calls to extend capital gains taxes to cover the sale of primary residences, applying at least to sales at the more expensive end of the market.

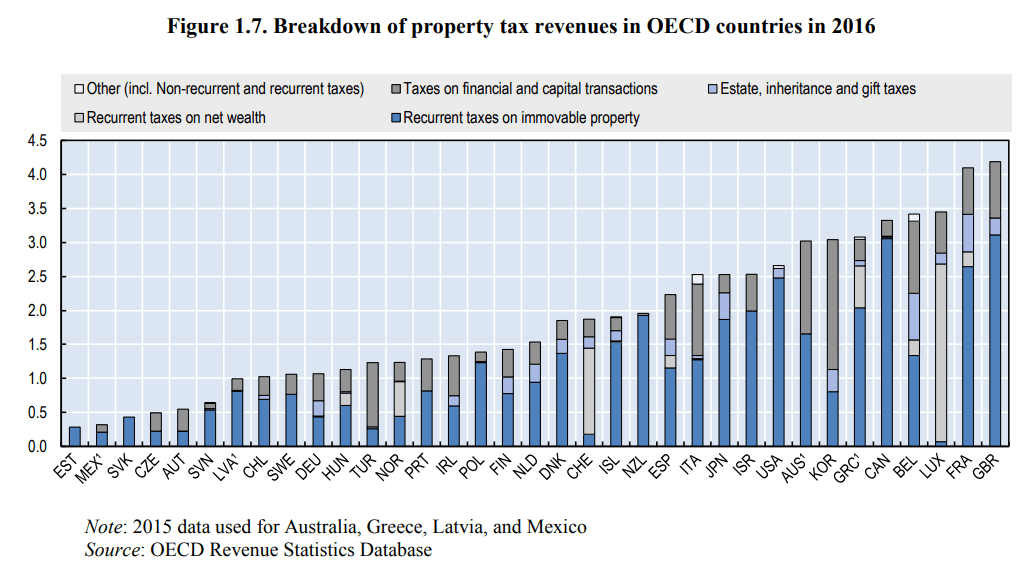

The nature and structure of existing taxes are not without controversy: CGT is argued to be too low and distortionary with rates out-of-kilter with higher income tax bands; stamp duty impedes transactions and thus an efficient market reallocation of homes; and council tax is based on values set in April 1991, which today do not reflect the subsequent, substantial shift in relative prices between geographical regions and housing categories. Despite this taxation mish mash and calls for more, the UK already raises more revenue via taxes on property than most OECD countries (see Chart).

Helping to drive the argument for more property taxes are high levels of real price inflation in the residential property market that has occurred for most of the last half a century. Because of seemingly rapid inflation, houses are purchased not only for accommodation but as an investment vehicle, the gain from which many critics see as driven by restrictive controls on land use and thus unjustified.

A couple of years ago in the Daily Telegraph I argued investing in property might not be quite the money spinner presumed because of limitations in compiling the all-important house price indices. Such indices are likely to influence a new tax regime and, therefore, it bears repeating why the standard indices might give a faulty reading of residential property price increases. In essence it is because they are not adjusted adequately for widespread, continuous, incremental quality improvements made to the existing stock of dwellings by their occupying owners; they are not true constant-quality indices.

The operative word here is adequately. The major compilers of price indices, (Halifax, Nationwide and HMRC) do make considerable efforts when upgrading their nominal price data on a regular monthly basis, to adjust for sales by differing property type and for different geographical areas, using hedonic pricing methodologies. Thus, when a recently sold property is recognised as having been upgraded significantly, for example when a three-bedroom property adds an additional bedroom, it is re-classified as having four beds; its new, inflated value no longer relates to three bed properties thus distorting prices for the latter.

Nevertheless, limitations remain. Only a minority of annual housing up-grades and improvements, albeit the most transformational, are allowed for by the hedonic pricing methodology. When planning permission is granted and works undertaken, an ‘improvement indicator’ (IC) is listed against a property and when next sold, it is subject to examination by the Valuations Office, a branch of HMRC, to see whether the works are such as to propel the property into a higher council tax band.

We do not have comprehensive details of annual IC numbers but we do know from a Freedom of Information request some years ago that at the end of 2018, 6 per cent of properties in England and Wales had an IC attached (1.65mn) and we also know that about 20 per cent of such properties merited a council tax re-banding leaving over a million improved and up-graded properties not re-classified.

It is possible, however, that these numbers scratch the surface of quality enhancements made to the existing stock of residential property. Post-1948 houses not in protected areas (conservation areas, national parks etc) can use Permitted Development Rights, to extend and upgrade in various ways: undertake loft conversions, add conservatories, garden rooms, upgrading heating systems, kitchens and bathrooms, without the need for formal planning permission (although there are complex rules to be followed). Additionally, small fortunes can be spent on landscaping gardens to enhance properties.

Estimating the relevant investment spending that the price indices fail to register and incorporate is, to say the least, challenging. The house (and garden) improvement industry is of considerable size, and the challenge is to try to distinguish spending on numerous small value-enhancing improvements from large, the latter more likely captured in the hedonic methods of the indices’ compilers. Also to be allowed for and discounted in any calculation, is the undoubtably huge spending on house maintenance and repairs that are incurred to keep property in a steady state condition.

ONS surveys show that the construction sector has the largest number of UK businesses and the SME component in that sector, the component most likely aligned with house improvement and renovation, numbers an astonishing 885,000. ONS statistics also show a spending of £34bn on private home repairs and maintenance in 2024. Approximately half of 1000 homeowners in a recent survey undertook renovations at a median cost of just over £21,000. With 25 million houses in the UK, the majority privately owned, those figures if extrapolated would imply implausible levels of spending on upgrading the quality of the housing stock.

Nevertheless, after discounting basic repair and maintenance, and allowing for major changes to existing housing stock captured in the hedonic pricing methods of Halifax and Nationwide, it is not unreasonable to suggest that enough is spent on countless more minor improvements to shift the dial of the house price indices. Over time, even an annual 0.5% shift, approximately a sixth of the overall annual increase over the last few years, when compounded, produces a significant difference. For example, over the period since 2010 (post financial crash) the difference in an index today attributed to a 0.5% annual figure would be close to 8%.

This suggests caution when considering revised residential property taxes. If capital gains on principal homes are to be taxed, or local council tax made proportional to asset prices, it seems necessary to obtain a better understanding of the underlying drivers for house price inflation. There is a substantial risk that an ill-considered revision to property taxation reduces householder incentives to upgrade property, damages the small business end of the construction industry, its supply chain, and the not insignificant VAT and employment tax receipts produced from it. It would be unfortunate also if the regular, but valuable up-dating of the nation’s housing stock was dis-incentivised by poorly designed tax increases.

Additional taxes, therefore, need to be carefully considered, at a minimum allowing, as is done for second home sales, for CGT relief on capital spending on upgrades and improvements. Even better would be to simplify tax complexity and focus on the pure property rent component by introducing a land value tax. It would be a radical departure from the status quo, and it would take time to compile what in effect would be a new Doomsday Book. But as matters stand, the real danger is that a thoughtless property tax revision or supplementary charges, risks damage to the huge number of small businesses operating in the sector and, crucially, to prospects for future economic growth.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Insider. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Paid subscribers support the IEA's charitable mission and receive special invites to exclusive events, including the thought-provoking IEA Book Club.

We are offering all new subscribers a special offer. For a limited time only, you will receive 15% off and a complimentary copy of Dr Stephen Davies’ latest book, Apocalypse Next: The Economics of Global Catastrophic Risks.