Email

The Misdirected Debate Over Medicaid And Obamacare

| From | Eugene Steuerle & The Government We Deserve <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The Misdirected Debate Over Medicaid And Obamacare |

| Date | November 7, 2025 2:55 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

Once again, Republicans and Democrats in Congress used the fight over that small portion of the budget subject to annual appropriations to engage in another shutdown, this time the longest in U.S. history. The main dispute over reaching a deal centered on whether two recent expansions of the nation’s government-funded health system should continue.

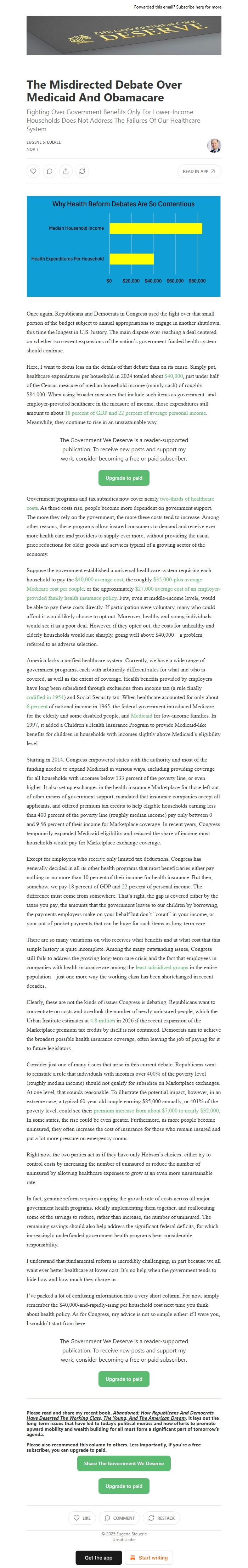

Here, I want to focus less on the details of that debate than on its cause. Simply put, healthcare expenditures per household in 2024 totaled about $40,000 [ [link removed] ], just under half of the Census measure of median household income (mainly cash) of roughly $84,000. When using broader measures that include such items as government- and employer-provided healthcare in the measure of income, those expenditures still amount to about 18 percent of GDP and 22 percent of average personal income [ [link removed] ]. Meanwhile, they continue to rise in an unsustainable way.

The Government We Deserve is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Government programs and tax subsidies now cover nearly two-thirds of healthcare costs [ [link removed] ]. As these costs rise, people become more dependent on government support. The more they rely on the government, the more these costs tend to increase. Among other reasons, these programs allow insured consumers to demand and receive ever more health care and providers to supply ever more, without providing the usual price reductions for older goods and services typical of a growing sector of the economy.

Suppose the government established a universal healthcare system requiring each household to pay the $40,000 average cost [ [link removed] ], the roughly $35,000-plus average Medicare cost per couple [ [link removed] ], or the approximately $27,000 average cost of an employer-provided family health insurance policy [ [link removed] ]. Few, even at middle-income levels, would be able to pay these costs directly. If participation were voluntary, many who could afford it would likely choose to opt out. Moreover, healthy and young individuals would see it as a poor deal. However, if they opted out, the costs for unhealthy and elderly households would rise sharply, going well above $40,000—a problem referred to as adverse selection.

America lacks a unified healthcare system. Currently, we have a wide range of government programs, each with arbitrarily different rules for what and who is covered, as well as the extent of coverage. Health benefits provided by employers have long been subsidized through exclusions from income tax (a rule finally codified in 1954 [ [link removed] ]) and Social Security tax. When healthcare accounted for only about 6 percent [ [link removed] ] of national income in 1965, the federal government introduced Medicare for the elderly and some disabled people, and Medicaid [ [link removed] ] for low-income families. In 1997, it added a Children’s Health Insurance Program to provide Medicaid-like benefits for children in households with incomes slightly above Medicaid’s eligibility level.

Starting in 2014, Congress empowered states with the authority and most of the funding needed to expand Medicaid in various ways, including providing coverage for all households with incomes below 133 percent of the poverty line, or even higher. It also set up exchanges in the health insurance Marketplace for those left out of other means of government support, mandated that insurance companies accept all applicants, and offered premium tax credits to help eligible households earning less than 400 percent of the poverty line (roughly median income) pay only between 0 and 9.56 percent of their income for Marketplace coverage. In recent years, Congress temporarily expanded Medicaid eligibility and reduced the share of income most households would pay for Marketplace exchange coverage.

Except for employees who receive only limited tax deductions, Congress has generally decided in all its other health programs that most beneficiaries either pay nothing or no more than 10 percent of their income for health insurance. But then, somehow, we pay 18 percent of GDP and 22 percent of personal income. The difference must come from somewhere. That’s right, the gap is covered either by the taxes you pay, the amounts that the government leaves to our children by borrowing, the payments employers make on your behalf but don’t “count” in your income, or your out-of-pocket payments that can be huge for such items as long-term care.

There are so many variations on who receives what benefits and at what cost that this simple history is quite incomplete. Among the many outstanding issues, Congress still fails to address the growing long-term care crisis and the fact that employees in companies with health insurance are among the least subsidized groups [ [link removed] ] in the entire population—just one more way the working class has been shortchanged in recent decades.

Clearly, these are not the kinds of issues Congress is debating. Republicans want to concentrate on costs and overlook the number of newly uninsured people, which the Urban Institute estimates at 4.8 million [ [link removed] ] in 2026 if the recent expansion of the Marketplace premium tax credits by itself is not continued. Democrats aim to achieve the broadest possible health insurance coverage, often leaving the job of paying for it to future legislators.

Consider just one of many issues that arise in this current debate. Republicans want to reinstate a rule that individuals with incomes over 400% of the poverty level (roughly median income) should not qualify for subsidies on Marketplace exchanges. At one level, that sounds reasonable. To illustrate the potential impact, however, in an extreme case, a typical 60-year-old couple earning $85,000 annually, or 401% of the poverty level, could see their premium increase from about $7,000 to nearly $32,000 [ [link removed] ]. In some states, the rise could be even greater. Furthermore, as more people become uninsured, they often increase the cost of insurance for those who remain insured and put a lot more pressure on emergency rooms.

Right now, the two parties act as if they have only Hobson’s choices: either try to control costs by increasing the number of uninsured or reduce the number of uninsured by allowing healthcare expenses to grow at an even more unsustainable rate.

In fact, genuine reform requires capping the growth rate of costs across all major government health programs, ideally implementing them together, and reallocating some of the savings to reduce, rather than increase, the number of uninsured. The remaining savings should also help address the significant federal deficits, for which increasingly underfunded government health programs bear considerable responsibility.

I understand that fundamental reform is incredibly challenging, in part because we all want ever better healthcare at lower cost. It’s no help when the government tends to hide how and how much they charge us.

I’ve packed a lot of confusing information into a very short column. For now, simply remember the $40,000-and-rapidly-ising per household cost next time you think about health policy. As for Congress, my advice is not so simple either: if I were you, I wouldn’t start from here.

The Government We Deserve is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Once again, Republicans and Democrats in Congress used the fight over that small portion of the budget subject to annual appropriations to engage in another shutdown, this time the longest in U.S. history. The main dispute over reaching a deal centered on whether two recent expansions of the nation’s government-funded health system should continue.

Here, I want to focus less on the details of that debate than on its cause. Simply put, healthcare expenditures per household in 2024 totaled about $40,000 [ [link removed] ], just under half of the Census measure of median household income (mainly cash) of roughly $84,000. When using broader measures that include such items as government- and employer-provided healthcare in the measure of income, those expenditures still amount to about 18 percent of GDP and 22 percent of average personal income [ [link removed] ]. Meanwhile, they continue to rise in an unsustainable way.

The Government We Deserve is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Government programs and tax subsidies now cover nearly two-thirds of healthcare costs [ [link removed] ]. As these costs rise, people become more dependent on government support. The more they rely on the government, the more these costs tend to increase. Among other reasons, these programs allow insured consumers to demand and receive ever more health care and providers to supply ever more, without providing the usual price reductions for older goods and services typical of a growing sector of the economy.

Suppose the government established a universal healthcare system requiring each household to pay the $40,000 average cost [ [link removed] ], the roughly $35,000-plus average Medicare cost per couple [ [link removed] ], or the approximately $27,000 average cost of an employer-provided family health insurance policy [ [link removed] ]. Few, even at middle-income levels, would be able to pay these costs directly. If participation were voluntary, many who could afford it would likely choose to opt out. Moreover, healthy and young individuals would see it as a poor deal. However, if they opted out, the costs for unhealthy and elderly households would rise sharply, going well above $40,000—a problem referred to as adverse selection.

America lacks a unified healthcare system. Currently, we have a wide range of government programs, each with arbitrarily different rules for what and who is covered, as well as the extent of coverage. Health benefits provided by employers have long been subsidized through exclusions from income tax (a rule finally codified in 1954 [ [link removed] ]) and Social Security tax. When healthcare accounted for only about 6 percent [ [link removed] ] of national income in 1965, the federal government introduced Medicare for the elderly and some disabled people, and Medicaid [ [link removed] ] for low-income families. In 1997, it added a Children’s Health Insurance Program to provide Medicaid-like benefits for children in households with incomes slightly above Medicaid’s eligibility level.

Starting in 2014, Congress empowered states with the authority and most of the funding needed to expand Medicaid in various ways, including providing coverage for all households with incomes below 133 percent of the poverty line, or even higher. It also set up exchanges in the health insurance Marketplace for those left out of other means of government support, mandated that insurance companies accept all applicants, and offered premium tax credits to help eligible households earning less than 400 percent of the poverty line (roughly median income) pay only between 0 and 9.56 percent of their income for Marketplace coverage. In recent years, Congress temporarily expanded Medicaid eligibility and reduced the share of income most households would pay for Marketplace exchange coverage.

Except for employees who receive only limited tax deductions, Congress has generally decided in all its other health programs that most beneficiaries either pay nothing or no more than 10 percent of their income for health insurance. But then, somehow, we pay 18 percent of GDP and 22 percent of personal income. The difference must come from somewhere. That’s right, the gap is covered either by the taxes you pay, the amounts that the government leaves to our children by borrowing, the payments employers make on your behalf but don’t “count” in your income, or your out-of-pocket payments that can be huge for such items as long-term care.

There are so many variations on who receives what benefits and at what cost that this simple history is quite incomplete. Among the many outstanding issues, Congress still fails to address the growing long-term care crisis and the fact that employees in companies with health insurance are among the least subsidized groups [ [link removed] ] in the entire population—just one more way the working class has been shortchanged in recent decades.

Clearly, these are not the kinds of issues Congress is debating. Republicans want to concentrate on costs and overlook the number of newly uninsured people, which the Urban Institute estimates at 4.8 million [ [link removed] ] in 2026 if the recent expansion of the Marketplace premium tax credits by itself is not continued. Democrats aim to achieve the broadest possible health insurance coverage, often leaving the job of paying for it to future legislators.

Consider just one of many issues that arise in this current debate. Republicans want to reinstate a rule that individuals with incomes over 400% of the poverty level (roughly median income) should not qualify for subsidies on Marketplace exchanges. At one level, that sounds reasonable. To illustrate the potential impact, however, in an extreme case, a typical 60-year-old couple earning $85,000 annually, or 401% of the poverty level, could see their premium increase from about $7,000 to nearly $32,000 [ [link removed] ]. In some states, the rise could be even greater. Furthermore, as more people become uninsured, they often increase the cost of insurance for those who remain insured and put a lot more pressure on emergency rooms.

Right now, the two parties act as if they have only Hobson’s choices: either try to control costs by increasing the number of uninsured or reduce the number of uninsured by allowing healthcare expenses to grow at an even more unsustainable rate.

In fact, genuine reform requires capping the growth rate of costs across all major government health programs, ideally implementing them together, and reallocating some of the savings to reduce, rather than increase, the number of uninsured. The remaining savings should also help address the significant federal deficits, for which increasingly underfunded government health programs bear considerable responsibility.

I understand that fundamental reform is incredibly challenging, in part because we all want ever better healthcare at lower cost. It’s no help when the government tends to hide how and how much they charge us.

I’ve packed a lot of confusing information into a very short column. For now, simply remember the $40,000-and-rapidly-ising per household cost next time you think about health policy. As for Congress, my advice is not so simple either: if I were you, I wouldn’t start from here.

The Government We Deserve is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a