Email

Hope In The Face of Backlash

| From | William Barber & Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Hope In The Face of Backlash |

| Date | October 28, 2025 8:25 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

It’s class day on campus at Yale Divinity School, and I’m aware that many Our Moral Moment readers are asking questions similar to those we hear from our students: where can we look for models of the moral leadership that’s needed right now? How do we learn from the past in ways that can equip us to face an unprecedented crisis?

I wanted to share two resources if these are the kinds of questions you’re asking:

The first is a book by Aran Shetterly about Nelson and Joyce Johnson, two of the most important moral leaders I’ve had a chance to learn from in my life. I reviewed Shetterley’s fabulous book, Morningside, for The Christian Century [ [link removed] ] magazine. The full text is below.

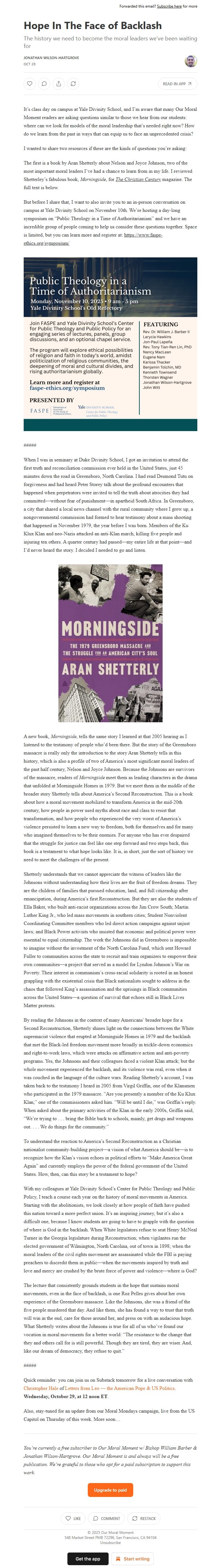

But before I share that, I want to also invite you to an in-person conversation on campus at Yale Divinity School on November 10th. We’re hosting a day-long symposium on “Public Theology in a Time of Authoritarianism” and we have an incredible group of people coming to help us consider these questions together. Space is limited, but you can learn more and register at: [link removed] [ [link removed] ]

#####

When I was in seminary at Duke Divinity School, I got an invitation to attend the first truth and reconciliation commission ever held in the United States, just 45 minutes down the road in Greensboro, North Carolina. I had read Desmond Tutu on forgiveness and had heard Peter Storey talk about the profound encounters that happened when perpetrators were invited to tell the truth about atrocities they had committed—without fear of punishment—in apartheid South Africa. In Greensboro, a city that shared a local news channel with the rural community where I grew up, a nongovernmental commission had formed to hear testimony about a mass shooting that happened in November 1979, the year before I was born. Members of the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis attacked an anti-Klan march, killing five people and injuring ten others. A quarter century had passed—my entire life at that point—and I’d never heard the story. I decided I needed to go and listen.

A new book, Morningside, tells the same story I learned at that 2005 hearing as I listened to the testimony of people who’d been there. But the story of the Greensboro massacre is really only the introduction to the story Aran Shetterly tells in this history, which is also a profile of two of America’s most significant moral leaders of the past half century, Nelson and Joyce Johnson. Because the Johnsons are survivors of the massacre, readers of Morningside meet them as leading characters in the drama that unfolded at Morningside Homes in 1979. But we meet them in the middle of the broader story Shetterly tells about America’s Second Reconstruction. This is a book about how a moral movement mobilized to transform America in the mid-20th century, how people in power used myths about race and class to resist that transformation, and how people who experienced the very worst of America’s violence persisted to learn a new way to freedom, both for themselves and for many who imagined themselves to be their enemies. For anyone who has ever despaired that the struggle for justice can feel like one step forward and two steps back, this book is a testament to what hope looks like. It is, in short, just the sort of history we need to meet the challenges of the present.

Shetterly understands that we cannot appreciate the witness of leaders like the Johnsons without understanding how their lives are the fruit of freedom dreams. They are the children of families that pursued education, land, and full citizenship after emancipation, during America’s first Reconstruction. But they are also the students of Ella Baker, who built anti-racist organizations across the Jim Crow South; Martin Luther King Jr., who led mass movements in southern cities; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee members who led direct action campaigns against unjust laws; and Black Power activists who insisted that economic and political power were essential to equal citizenship. The work the Johnsons did in Greensboro is impossible to imagine without the investment of the North Carolina Fund, which sent Howard Fuller to communities across the state to recruit and train organizers to empower their own communities—a project that served as a model for Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Their interest in communism’s cross-racial solidarity is rooted in an honest grappling with the existential crisis that Black nationalists sought to address in the chaos that followed King’s assassination and the uprisings in Black communities across the United States—a question of survival that echoes still in Black Lives Matter protests.

By reading the Johnsons in the context of many Americans’ broader hope for a Second Reconstruction, Shetterly shines light on the connections between the White supremacist violence that erupted at Morningside Homes in 1979 and the backlash that met the Black-led freedom movement more broadly in trickle-down economics and right-to-work laws, which were attacks on affirmative action and anti-poverty programs. Yes, the Johnsons and their colleagues faced a violent Klan attack; but the whole movement experienced the backlash, and its violence was real, even when it was couched in the language of the culture wars. Reading Shetterly’s account, I was taken back to the testimony I heard in 2005 from Virgil Griffin, one of the Klansmen who participated in the 1979 massacre. “Are you presently a member of the Ku Klux Klan,” one of the commissioners asked him. “Will be until I die,” was Griffin’s reply. When asked about the primary activities of the Klan in the early 2000s, Griffin said, “We’re trying to . . . bring the Bible back to schools, mainly, get drugs and weapons out. . . . We do things for the community.”

To understand the reaction to America’s Second Reconstruction as a Christian nationalist community-building project—a vision of what America should be—is to recognize how the Klan’s vision echoes in political efforts to “Make America Great Again” and currently employs the power of the federal government of the United States. How, then, can this story be a testament to hope?

With my colleagues at Yale Divinity School’s Center for Public Theology and Public Policy, I teach a course each year on the history of moral movements in America. Starting with the abolitionists, we look closely at how people of faith have pushed this nation toward a more perfect union. It’s an inspiring journey, but it’s also a difficult one, because I know students are going to have to grapple with the question of where is God in the backlash. When White legislators refuse to seat Henry McNeal Turner in the Georgia legislature during Reconstruction; when vigilantes run the elected government of Wilmington, North Carolina, out of town in 1898; when the moral leaders of the civil rights movement are assassinated while the FBI is paying preachers to discredit them in public—when the movements inspired by truth and love and mercy are crushed by the brute force of power and violence—where is God?

The lecture that consistently grounds students in the hope that sustains moral movements, even in the face of backlash, is one Roz Pelles gives about her own experience of the Greensboro massacre. Like the Johnsons, she was a friend of the five people murdered that day. And like them, she has found a way to trust that truth will win in the end, care for those around her, and press on with an audacious hope. What Shetterly writes about the Johnsons is true for all of us who’ve found our vocation in moral movements for a better world: “The resistance to the change that they and others call for is still powerful. Though they are tired, they are wiser. And, like our dream of democracy, they refuse to quit.”

#####

Quick reminder: you can join us on Substack tomorrow for a live conversation with Christopher Hale of Letters from Leo — the American Pope & US Politics . Wednesday, October 29, at 12 noon ET.

Also, stay-tuned for an update from our Moral Mondays campaign, live from the US Capitol on Thursday of this week. More soon…

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

It’s class day on campus at Yale Divinity School, and I’m aware that many Our Moral Moment readers are asking questions similar to those we hear from our students: where can we look for models of the moral leadership that’s needed right now? How do we learn from the past in ways that can equip us to face an unprecedented crisis?

I wanted to share two resources if these are the kinds of questions you’re asking:

The first is a book by Aran Shetterly about Nelson and Joyce Johnson, two of the most important moral leaders I’ve had a chance to learn from in my life. I reviewed Shetterley’s fabulous book, Morningside, for The Christian Century [ [link removed] ] magazine. The full text is below.

But before I share that, I want to also invite you to an in-person conversation on campus at Yale Divinity School on November 10th. We’re hosting a day-long symposium on “Public Theology in a Time of Authoritarianism” and we have an incredible group of people coming to help us consider these questions together. Space is limited, but you can learn more and register at: [link removed] [ [link removed] ]

#####

When I was in seminary at Duke Divinity School, I got an invitation to attend the first truth and reconciliation commission ever held in the United States, just 45 minutes down the road in Greensboro, North Carolina. I had read Desmond Tutu on forgiveness and had heard Peter Storey talk about the profound encounters that happened when perpetrators were invited to tell the truth about atrocities they had committed—without fear of punishment—in apartheid South Africa. In Greensboro, a city that shared a local news channel with the rural community where I grew up, a nongovernmental commission had formed to hear testimony about a mass shooting that happened in November 1979, the year before I was born. Members of the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis attacked an anti-Klan march, killing five people and injuring ten others. A quarter century had passed—my entire life at that point—and I’d never heard the story. I decided I needed to go and listen.

A new book, Morningside, tells the same story I learned at that 2005 hearing as I listened to the testimony of people who’d been there. But the story of the Greensboro massacre is really only the introduction to the story Aran Shetterly tells in this history, which is also a profile of two of America’s most significant moral leaders of the past half century, Nelson and Joyce Johnson. Because the Johnsons are survivors of the massacre, readers of Morningside meet them as leading characters in the drama that unfolded at Morningside Homes in 1979. But we meet them in the middle of the broader story Shetterly tells about America’s Second Reconstruction. This is a book about how a moral movement mobilized to transform America in the mid-20th century, how people in power used myths about race and class to resist that transformation, and how people who experienced the very worst of America’s violence persisted to learn a new way to freedom, both for themselves and for many who imagined themselves to be their enemies. For anyone who has ever despaired that the struggle for justice can feel like one step forward and two steps back, this book is a testament to what hope looks like. It is, in short, just the sort of history we need to meet the challenges of the present.

Shetterly understands that we cannot appreciate the witness of leaders like the Johnsons without understanding how their lives are the fruit of freedom dreams. They are the children of families that pursued education, land, and full citizenship after emancipation, during America’s first Reconstruction. But they are also the students of Ella Baker, who built anti-racist organizations across the Jim Crow South; Martin Luther King Jr., who led mass movements in southern cities; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee members who led direct action campaigns against unjust laws; and Black Power activists who insisted that economic and political power were essential to equal citizenship. The work the Johnsons did in Greensboro is impossible to imagine without the investment of the North Carolina Fund, which sent Howard Fuller to communities across the state to recruit and train organizers to empower their own communities—a project that served as a model for Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Their interest in communism’s cross-racial solidarity is rooted in an honest grappling with the existential crisis that Black nationalists sought to address in the chaos that followed King’s assassination and the uprisings in Black communities across the United States—a question of survival that echoes still in Black Lives Matter protests.

By reading the Johnsons in the context of many Americans’ broader hope for a Second Reconstruction, Shetterly shines light on the connections between the White supremacist violence that erupted at Morningside Homes in 1979 and the backlash that met the Black-led freedom movement more broadly in trickle-down economics and right-to-work laws, which were attacks on affirmative action and anti-poverty programs. Yes, the Johnsons and their colleagues faced a violent Klan attack; but the whole movement experienced the backlash, and its violence was real, even when it was couched in the language of the culture wars. Reading Shetterly’s account, I was taken back to the testimony I heard in 2005 from Virgil Griffin, one of the Klansmen who participated in the 1979 massacre. “Are you presently a member of the Ku Klux Klan,” one of the commissioners asked him. “Will be until I die,” was Griffin’s reply. When asked about the primary activities of the Klan in the early 2000s, Griffin said, “We’re trying to . . . bring the Bible back to schools, mainly, get drugs and weapons out. . . . We do things for the community.”

To understand the reaction to America’s Second Reconstruction as a Christian nationalist community-building project—a vision of what America should be—is to recognize how the Klan’s vision echoes in political efforts to “Make America Great Again” and currently employs the power of the federal government of the United States. How, then, can this story be a testament to hope?

With my colleagues at Yale Divinity School’s Center for Public Theology and Public Policy, I teach a course each year on the history of moral movements in America. Starting with the abolitionists, we look closely at how people of faith have pushed this nation toward a more perfect union. It’s an inspiring journey, but it’s also a difficult one, because I know students are going to have to grapple with the question of where is God in the backlash. When White legislators refuse to seat Henry McNeal Turner in the Georgia legislature during Reconstruction; when vigilantes run the elected government of Wilmington, North Carolina, out of town in 1898; when the moral leaders of the civil rights movement are assassinated while the FBI is paying preachers to discredit them in public—when the movements inspired by truth and love and mercy are crushed by the brute force of power and violence—where is God?

The lecture that consistently grounds students in the hope that sustains moral movements, even in the face of backlash, is one Roz Pelles gives about her own experience of the Greensboro massacre. Like the Johnsons, she was a friend of the five people murdered that day. And like them, she has found a way to trust that truth will win in the end, care for those around her, and press on with an audacious hope. What Shetterly writes about the Johnsons is true for all of us who’ve found our vocation in moral movements for a better world: “The resistance to the change that they and others call for is still powerful. Though they are tired, they are wiser. And, like our dream of democracy, they refuse to quit.”

#####

Quick reminder: you can join us on Substack tomorrow for a live conversation with Christopher Hale of Letters from Leo — the American Pope & US Politics . Wednesday, October 29, at 12 noon ET.

Also, stay-tuned for an update from our Moral Mondays campaign, live from the US Capitol on Thursday of this week. More soon…

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a