|

|

Is Private Credit's "Fender Bender" about to become a major pileup?

Are Subprime auto loans the reboot of 2008 no one wants?

The Capitalist is a reader-supported publication

Reject Corporate Left Wing Journalism

In the sun-baked lots of Dallas, where the air shimmers off rows of gleaming used sedans, Tricolor Auto Acceptance once promised a path to mobility for the overlooked. Founded in 2007 as a “buy-here-pay-here” lender targeting Hispanic and immigrant communities with thin credit files, the company blended dealership sales with in-house financing, extending loans to those who banks deemed too risky. It was a model born of inclusion—or so it seemed.

By 2024, Tricolor had originated nearly $1 billion in subprime auto loans annually, its AI-driven assessments touted as a democratizing force in a market where traditional lenders recoiled from the subprime fray. But then the facade crumbled. Allegations of fraud—double-pledged collateral, doctored loan portfolio documentation, loans made to illegal immigrants without an income or even a drivers license termed “social lending”—led to a Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing in Texas, listing $1 billion to $10 billion in assets and liabilities, ensnaring over 25,000 creditors.

Fifth Third Bancorp alone booked a $178 million loss on a $200 million warehouse loan, while JPMorgan Chase absorbed $170 million in charge-offs. The trustee’s report hinted at “systemic levels of fraud,” a phrase that echoed through boardrooms like a long distant memory of a thunderclap from 17 years ago.

This is not an isolated tremor. Across the sprawl of America’s used-car ecosystem, private credit—the shadowy counterpart to public bonds and bank loans—has woven itself into the fabric of everyday aspiration. A very visible sign of this is the massive increase in “Buy now, Pay later” companies such as Affirm and Klarna. What began as a niche for distressed borrowers now underpins a $3 trillion market, ballooning from $2 trillion in 2020 amid post-pandemic fervor and regulatory squeezes on banks.

Sponsored By Vision Breakthrough

Restore your 20/20 vision naturally by do THIS every morning

Yet as delinquencies climb and firms falter, a question is nagging: Is private credit inflating a bubble destined to burst in the nation’s garages, dragging down the working families it claims to uplift? The answer lies not in alarmism, but in the quiet mechanics of a system that trades speed for scrutiny, yield for opacity.

Private credit diverges sharply from the staid world of bank lending. Banks, bound by federal oversight like the Dodd-Frank Act, must hold substantial capital reserves against loans—often 8% or more of the principal—to buffer against defaults.

Their processes are deliberate: rigorous credit checks, collateral appraisals, and public disclosures that invite market discipline. Private credit, by contrast, operates in the ether of direct negotiations between non-bank lenders—think hedge funds, pension pools, or boutique firms like Apollo Global Management—and borrowers.

These deals are bespoke, often senior secured loans, (they have the first in line for repayment over other debt, and secured against specific collateral like real estate or equipment) with floating rates - tied to benchmarks like the Secured Overnight Financing Rate set by the Treasury, and promising yields of 10% to 12% in a low-rate era.

No public filings.

No SEC scrutiny.

Just covenants buried in confidential term sheets.

They’re pay day loans for companies.

Companies flock to this arena for its velocity. A midsize auto supplier, starved for inventory amid supply-chain snarls, can secure $500 million overnight without the bureaucratic drag of going through due diligence at a bank.

That due diligence exists for a reason. The Basel III reforms instituted in 2012, hiked the amount of money banks were required to hold in relation to riskier loans. The intention was to make sure that nothing like 2008’s subprime mortgage explosion could ever happen again. As a result of the regulations, subprime plays by banks were no longer profitable so they largely exited that game. But just because banks couldn’t play the subprime game anymore didn’t mean the subprime game vanished, it simply left a void, a void that Private credit swept in to fill.

In 2025, as the Federal Reserve’s stubbornness to lower rates bit into consumer wallets, consequently private credit’s share of middle-market lending hit 70%, per Preqin data. It’s efficient, yes—but that efficiency masks perils. Without transparency, lenders chase volume over vetting, fostering “zombie firms” that limp along on an evergreen cycle of recirculating debt. Borrowers, meanwhile, leverage up in secrecy, their balance sheets become a black box with a faint ticking sound coming from inside it until insolvency strikes

No sector exemplifies this tension like used cars, where private credit has become the lifeblood—and potential hemlock—of a $500 billion annual market. Why the entanglement? The used-car trade thrives on subprime borrowers: 55% of purchases are financed, with average FICO scores dipping below 600 for many, per Experian. New cars, buoyed by manufacturer incentives, draw prime credit from captive lenders like Toyota Financial.

But used vehicles—affordable relics of pandemic-era price surges—lure the credit-impaired, who face APRs north of 20%. Private credit steps in because banks, wary of repossession logistics and regulatory heat, ceded this turf.

Firms then bundle these loans into asset-backed securities (ABS), slicing them into tranches where the riskiest absorb losses first.

In 2024, subprime auto ABS issuance topped $25 billion, much of it privately placed, as lenders bet on repossessable collateral: the cars themselves.

This symbiosis has supercharged growth but sown vulnerabilities. Used-car prices, still 30% above pre-2020 levels per Kelley Blue Book, amplify loan-to-value ratios, turning minor delinquencies into cascades. Private credit’s opacity exacerbates the issue: Investors in these ABS often lack granular data on borrower profiles or servicing quality. When inflation eroded savings—household financial fragility hit 40% in a 2024 Federal Reserve survey—the strain rippled upward.

Repossessions surged 20% year-over-year, per Cox Automotive, flooding lots with inventory and depressing values. It’s a feedback loop: Cheaper used cars should ease access, but eroded collateral erodes lender confidence, hiking rates and tightening credit further.

The wreckage is mounting. Tricolor’s implosion was merely the prelude. First Brands Group, an Ohio-based auto-parts maker, filed for Chapter 11 in late September, unveiling a $10 billion (at minimum) debt bomb laced with private credit. Acquired piecemeal through debt-fueled buys,—snapping up Autolite spark plugs and Raybestos brakes—First Brands debt total had ballooned, its $6 billion in junk bonds were merely the appetizer.

The real scandal however lurked “off-balance-sheet”: Billions in undisclosed private loans, including $715 million from Jefferies’ Point Bonita Capital secured against Walmart-bound inventory. Then it got worse. Creditors alleged $2.3 billion in assets “simply vanished,” as assets that loans were secured against were discovered to have been pledged multiple times over to different lenders like UBS and Nomura. The CEO’s abrupt resignation amid accounting probes has ignited investigations, with total losses projected in the tens of billions—a stark rebuke to private credit’s vaunted covenants.

Then came PrimaLend Capital Partners, the latest casualty. This subprime financier, armed buy-here-pay-here dealers with credit lines for sub-600 FICO buyers.

Apparently the “Strategic” lending “with tomorrow in mind” didn’t reach to the day after tomorrow because PrimaLend defaulted on a $75 million bond in mid-2025. Months of creditor wrangling culminated in a Chapter 11 filing on October 22. as Bloomberg first reported. PrimaLend, which originated loans at 33% average APRs, blamed “industry-wide headwinds” like inflation and rate hikes for its crash.

Yet its portfolio—tied to the same distressed used-car chain—mirrored Tricolor’s frailties: opaque servicing and an over reliance on ABS sales. With commitments for debtor-in-possession financing secured, it now eyes a sale, but the stain lingers. These collapses, clustered in auto’s underbelly, signal not contagion yet, but contagion’s preexisting conditions.

Wall Street’s gaze now fixes on Carvana, the e-commerce wunderkind whose 70% stock surge in 2025 masks deepening fissures. Once a meme-stock phoenix, Carvana derives 26% of gross profits from subprime loan sales, bundling them into $851 million ABS pools peddled to yield-hungry investors.

Delinquencies tell the tale of whats to come: 28.7% of its subprime loans are 30+ days past due, —four times the benchmark prime credit borrowers—and 12.7% are severely overdue. Carvana loan extensions, doled out via DriveTime Automotive Group, a servicer run by CEO Ernie Garcia III’s father, have ballooned, delaying defaults but inflating principal. Net debt hovers at $4.8 billion, 4.4 times EBITDA, with $215 million in annual cash interest kicking in February.

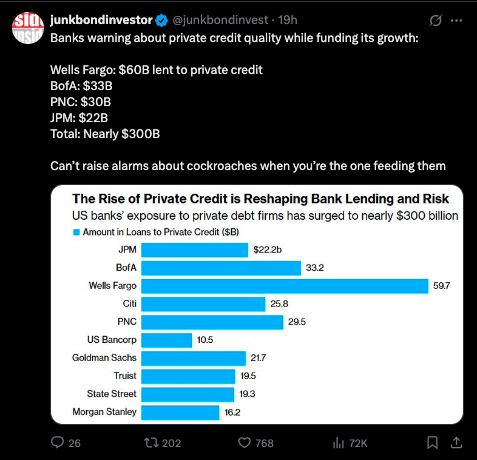

Hindenburg Research likens it to pre-2008 grift, citing governance red flags inside the company and Ally Financial’s $4 billion purchase commitment expiring January 2025. JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon, stung by Tricolor, dubbed such risks “cockroaches”: hidden until they swarm. Carvana insists tighter underwriting has stemmed the bleed—2025 sales show just 5-10% delinquencies—but in a wider economic downturn, its model could vaporize overnight.

Averting an industry wide meltdown demands reckoning with private credit’s Gordian knots. Foremost is opacity: Unlike public markets, where bond prices signal distress, private deals evade real-time pricing, breeding “evergreening.” Where companies in distress are always available to find loans regardless of how bad their financials are (Tricolor, First Brands) because there is always someone willing to loan them money for a high yield. The company becomes a zombie, surviving on a diet of constant debt and so long as the company doesn’t implode, the gravy train keeps running, but the implosions have begun to start.

Regulators like the SEC eye disclosure mandates, but enforcement lags; the $3 trillion pool dwarfs oversight capacity. Banks, dipping toes in via partnerships, face capital rules that deter deep dives, while pensions—holding 40% of these ABS assets, per Moody’s—chase yields above all else, blind to tail risks and what sinister horror dwells in the deep.

Intervention risks moral hazard: Bailouts echo 2008, yet inaction invites spillovers to Collateralized Loan Obligations (a type of bond made up of lots of corporate bonds bundled together) and leveraged loans, and all are interconnected via $1.7 trillion in auto debt.

The IMF warns of correlated shocks to come; a used-car rout could idle factories and spike unemployment in rust-belt towns. Policymakers might hike transparency via regulation, implementing European style Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) rules in the U.S., but regulation may not have the intended outcome. After all, the regulations to prevent banks dealing in subprime loans have singularly failed to achieve a safer financial world, they simply pushed subprime debts in to a world with even less oversight than they had before.

Also, as Dimon warned, where there is one cockroach there are more. Because Private credit and shadow banking is an opaque market, no one knows how many zombie firms are out there surviving on a diet of evergreening debt. Were it to dry up how many of those firms could withstand going cold turkey?

In the end, private credit’s used-car fixation reveals a deeper unease: an economy where mobility hinges on credit’s precarious scaffolding. As credit yields seduce institutions and startups alike, Tricolor borrowers, many of them low income, chasing the American dream, now face repossession’s sting, their vehicles—lifelines to their jobs—towed away.

For private credit the garage lights are flickering, the engines are still humming—for now, but did shadow banking fortify resilience or merely postpone fragility?

People were caught off guard by 2008, they couldn’t figure out what happened and why there were no warning signs. 2008 could be about to get a Hollywood remake and for anyone who wants a warning sign this time, Tricolor, First Brands and PrimaLend is the fender bender.

The 8 lane multi car pileup could be coming?

The Capitalist is a reader-supported publication

Reject Corporate Left Wing Journalism

You're currently a free subscriber to The Capitalist. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.