| From | Wayne Hsiung from The Simple Heart <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The Community That Changed Everything |

| Date | October 16, 2025 10:57 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

Look around you at the moment, and you’ll see unprecedented threats to the future of humanity. Government crackdowns on free speech. Global conflicts spiraling into humanitarian crisis. And new technologies that threaten to destroy life on earth. But the moment I’m speaking of is not 2025. It’s 1960. And even as the McCarthy Era exploded into foreign conflicts and fears of nuclear holocaust, something remarkable happened: movements arose from that dark moment to make the next decade among the brightest in American history.

And it started with four students in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The Simple Heart is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell A. Blair, Jr., and Joseph McNeil – all freshmen at North Carolina A&T – were not famous or powerful. Yet their actions arguably did more to change the world than the most renowned leaders of the 20th century. Their sit-in at a Woolworth in Greensboro grew from four activists to 1,000 in a mere five days, then exploded around the country like a rocket in a room full of fireworks. By the end of 1960, over 70,000 participated [ [link removed] ] in the sit-in movement, 3,000 had been arrested, and racial segregation was on the brink of collapse. Indeed, the Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam once told me that, while Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. are the more famous names, it was the Greensboro Four who created the most transformative change. Their sit-in movement triggered a national awakening not just on racial justice but also on imperialism (ending the Vietnam War), women’s rights (winning the legal right to contraception), and economic inequality (creating food stamps and Medicaid).

How did they do it?

There were a number of factors that made the sit-in movement such a powerful catalyst. First, the sit-ins were attention-grabbing. National newspapers covered the dramatic confrontations at lunch counters, triggering cycles of awareness and participation. Second, the sit-ins were accessible. Activists across the nation could easily feed into the cycle of attention by finding a local lunch counter and sitting in. Third, the sit-ins were nonviolent. The activists dressed up in their Sunday best, and even when counter-protesters spat in their faces, the activists responded, “I love you, brother, and I will treat you with respect.” This earned sympathy even among the movement’s critics.

But there was a fourth and mostly-ignored factor that was the most important: the sit-ins were born from a powerful community. The Greensboro Four, and many of the hundreds who followed them in the months to come, were not just fellow activists but friends. Over the months prior to their February action, the four NC A&T students were “inseparable [ [link removed] ]” on campus. They studied [ [link removed] ] together. They went to concerts together. They complained about their parents to each other. And, above all, they dreamed of a better world together, in daily dorm-room discussions [ [link removed] ] that went into the dead hours of the night.

Connections like these are crucial to creating change. Research by McAdam shows that strong ties between activists in the civil rights movement had a larger impact on participation in high-risk activism than all other factors combined [ [link removed] ]. Yet those ties of friendship, which were often fostered through civic institutions like churches, have disappeared in the modern world. When Americans are asked how many people they have in their lives to “discuss important matters,” the most common response is zero [ [link removed] ]. What the Greensboro Four did every day, most Americans never do at all.

So how do we reverse the decline in social connection, and build communities to take on the challenges of the 21st century? There is research on this question, too, and here are some of the most important (and surprising) insights.

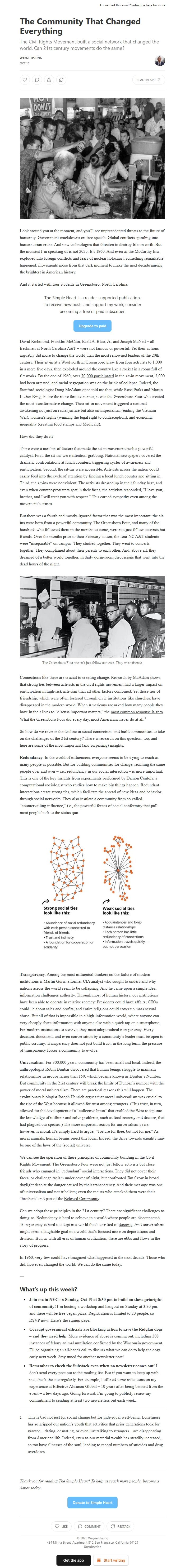

Redundancy. In the world of influencers, everyone seems to be trying to reach as many people as possible. But for building communities for change, reaching the same people over and over – i.e., redundancy in our social interaction – is more important. This is one of the key insights from experiments performed by Damon Centola, a computational sociologist who studies how to make big things happen [ [link removed] ]. Redundant interactions create strong ties, which facilitate the spread of new ideas and behavior through social networks. They also insulate a community from so-called “countervailing influence,” i.e., the powerful forces of social conformity that pull most people back to the status quo.

Transparency. Among the most influential thinkers on the failure of modern institutions is Martin Gurri, a former CIA analyst who sought to understand why nations across the world seem to be collapsing. And he came upon a simple idea: information challenges authority. Through most of human history, our institutions have been able to operate in relative secrecy: Presidents could have affairs; CEOs could lie about sales and profits; and entire religions could cover up mass sexual abuse. But all of that is impossible in a high-information world, where anyone can very cheaply share information with anyone else with a quick tap on a smartphone. For modern institutions to survive, they must adopt radical transparency. Every decision, document, and even conversation by a community’s leader must be open to public scrutiny. Transparency does not just build trust; in the long term, the pressure of transparency forces a community to evolve.

Universalism. For 300,000 years, community has been small and local. Indeed, the anthropologist Robin Dunbar discovered that human beings struggle to maintain relationships in groups larger than 150, which became known as Dunbar’s Number [ [link removed] ]. But community in the 21st century will break the limits of Dunbar’s number with the power of moral universalism. There are practical reasons this will happen. The evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich argues that moral universalism was crucial to the rise of the West because it allowed for trust among strangers. (This trust, in turn, allowed for the development of a “collective brain” that enabled the West to tap into the knowledge of millions and solve problems, such as food scarcity and disease, that had plagued our species.) The more important reason for universalism’s rise, however, is moral. It’s simply hard to argue, “Torture for thee, but not for me.” As moral animals, human beings reject this logic. Indeed, the drive towards equality may be one of the laws of the (social) universe [ [link removed] ].

We can see the operation of these principles of community building in the Civil Rights Movement. The Greensboro Four were not just fellow activists but close friends who engaged in “redundant” social interactions. They did not cover their faces, or challenge racism under cover of night, but confronted Jim Crow in broad daylight despite the danger caused by their transparency. And their message was one of universalism and not tribalism; even the racists who attacked them were their “brothers” and part of the Beloved Community [ [link removed] ].

Can we adopt these principles in the 21st century? There are significant challenges to doing so. Redundancy is hard to achieve in a world where people are disconnected. Transparency is hard to adopt in a world that’s terrified of doxxing [ [link removed] ]. And universalism might seem a laughable goal in a world that’s focused more on deportations and division. But, as with all eras of human civilization, there are ebbs and flows in the story of progress.

In 1960, very few could have imagined what happened in the next decade. Those who did, however, changed the world. We can do the same today.

—

What’s up this week?

Join me in NYC on Sunday, Oct 19 at 3:30 pm to build on these principles of community! I’m hosting a workshop and hangout on Sunday at 3:30 pm, and there will be free vegan pizza. Registration is limited to 20 people, so RSVP now! Here’s the signup page. [ [link removed] ]

Corrupt government officials are blocking action to save the Ridglan dogs – and they need help. More evidence of abuse is coming out, including 308 instances of felony animal mutilation confirmed by the Wisconsin government. I’ll be organizing an all-hands call to discuss what we can do to help the dogs early next week. Stay tuned for another newsletter post!

Remember to check the Substack even when no newsletter comes out! I don’t send every post out to the mailing list. But if you want to keep up with me, check the site regularly. For example, I offered some reflections on my experience at Effective Altruism Global – 10 years after being banned from the event – a few days ago. Going forward, I’m going to publicly renew my commitment to sending at least two newsletters out each week.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Look around you at the moment, and you’ll see unprecedented threats to the future of humanity. Government crackdowns on free speech. Global conflicts spiraling into humanitarian crisis. And new technologies that threaten to destroy life on earth. But the moment I’m speaking of is not 2025. It’s 1960. And even as the McCarthy Era exploded into foreign conflicts and fears of nuclear holocaust, something remarkable happened: movements arose from that dark moment to make the next decade among the brightest in American history.

And it started with four students in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The Simple Heart is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell A. Blair, Jr., and Joseph McNeil – all freshmen at North Carolina A&T – were not famous or powerful. Yet their actions arguably did more to change the world than the most renowned leaders of the 20th century. Their sit-in at a Woolworth in Greensboro grew from four activists to 1,000 in a mere five days, then exploded around the country like a rocket in a room full of fireworks. By the end of 1960, over 70,000 participated [ [link removed] ] in the sit-in movement, 3,000 had been arrested, and racial segregation was on the brink of collapse. Indeed, the Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam once told me that, while Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. are the more famous names, it was the Greensboro Four who created the most transformative change. Their sit-in movement triggered a national awakening not just on racial justice but also on imperialism (ending the Vietnam War), women’s rights (winning the legal right to contraception), and economic inequality (creating food stamps and Medicaid).

How did they do it?

There were a number of factors that made the sit-in movement such a powerful catalyst. First, the sit-ins were attention-grabbing. National newspapers covered the dramatic confrontations at lunch counters, triggering cycles of awareness and participation. Second, the sit-ins were accessible. Activists across the nation could easily feed into the cycle of attention by finding a local lunch counter and sitting in. Third, the sit-ins were nonviolent. The activists dressed up in their Sunday best, and even when counter-protesters spat in their faces, the activists responded, “I love you, brother, and I will treat you with respect.” This earned sympathy even among the movement’s critics.

But there was a fourth and mostly-ignored factor that was the most important: the sit-ins were born from a powerful community. The Greensboro Four, and many of the hundreds who followed them in the months to come, were not just fellow activists but friends. Over the months prior to their February action, the four NC A&T students were “inseparable [ [link removed] ]” on campus. They studied [ [link removed] ] together. They went to concerts together. They complained about their parents to each other. And, above all, they dreamed of a better world together, in daily dorm-room discussions [ [link removed] ] that went into the dead hours of the night.

Connections like these are crucial to creating change. Research by McAdam shows that strong ties between activists in the civil rights movement had a larger impact on participation in high-risk activism than all other factors combined [ [link removed] ]. Yet those ties of friendship, which were often fostered through civic institutions like churches, have disappeared in the modern world. When Americans are asked how many people they have in their lives to “discuss important matters,” the most common response is zero [ [link removed] ]. What the Greensboro Four did every day, most Americans never do at all.

So how do we reverse the decline in social connection, and build communities to take on the challenges of the 21st century? There is research on this question, too, and here are some of the most important (and surprising) insights.

Redundancy. In the world of influencers, everyone seems to be trying to reach as many people as possible. But for building communities for change, reaching the same people over and over – i.e., redundancy in our social interaction – is more important. This is one of the key insights from experiments performed by Damon Centola, a computational sociologist who studies how to make big things happen [ [link removed] ]. Redundant interactions create strong ties, which facilitate the spread of new ideas and behavior through social networks. They also insulate a community from so-called “countervailing influence,” i.e., the powerful forces of social conformity that pull most people back to the status quo.

Transparency. Among the most influential thinkers on the failure of modern institutions is Martin Gurri, a former CIA analyst who sought to understand why nations across the world seem to be collapsing. And he came upon a simple idea: information challenges authority. Through most of human history, our institutions have been able to operate in relative secrecy: Presidents could have affairs; CEOs could lie about sales and profits; and entire religions could cover up mass sexual abuse. But all of that is impossible in a high-information world, where anyone can very cheaply share information with anyone else with a quick tap on a smartphone. For modern institutions to survive, they must adopt radical transparency. Every decision, document, and even conversation by a community’s leader must be open to public scrutiny. Transparency does not just build trust; in the long term, the pressure of transparency forces a community to evolve.

Universalism. For 300,000 years, community has been small and local. Indeed, the anthropologist Robin Dunbar discovered that human beings struggle to maintain relationships in groups larger than 150, which became known as Dunbar’s Number [ [link removed] ]. But community in the 21st century will break the limits of Dunbar’s number with the power of moral universalism. There are practical reasons this will happen. The evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich argues that moral universalism was crucial to the rise of the West because it allowed for trust among strangers. (This trust, in turn, allowed for the development of a “collective brain” that enabled the West to tap into the knowledge of millions and solve problems, such as food scarcity and disease, that had plagued our species.) The more important reason for universalism’s rise, however, is moral. It’s simply hard to argue, “Torture for thee, but not for me.” As moral animals, human beings reject this logic. Indeed, the drive towards equality may be one of the laws of the (social) universe [ [link removed] ].

We can see the operation of these principles of community building in the Civil Rights Movement. The Greensboro Four were not just fellow activists but close friends who engaged in “redundant” social interactions. They did not cover their faces, or challenge racism under cover of night, but confronted Jim Crow in broad daylight despite the danger caused by their transparency. And their message was one of universalism and not tribalism; even the racists who attacked them were their “brothers” and part of the Beloved Community [ [link removed] ].

Can we adopt these principles in the 21st century? There are significant challenges to doing so. Redundancy is hard to achieve in a world where people are disconnected. Transparency is hard to adopt in a world that’s terrified of doxxing [ [link removed] ]. And universalism might seem a laughable goal in a world that’s focused more on deportations and division. But, as with all eras of human civilization, there are ebbs and flows in the story of progress.

In 1960, very few could have imagined what happened in the next decade. Those who did, however, changed the world. We can do the same today.

—

What’s up this week?

Join me in NYC on Sunday, Oct 19 at 3:30 pm to build on these principles of community! I’m hosting a workshop and hangout on Sunday at 3:30 pm, and there will be free vegan pizza. Registration is limited to 20 people, so RSVP now! Here’s the signup page. [ [link removed] ]

Corrupt government officials are blocking action to save the Ridglan dogs – and they need help. More evidence of abuse is coming out, including 308 instances of felony animal mutilation confirmed by the Wisconsin government. I’ll be organizing an all-hands call to discuss what we can do to help the dogs early next week. Stay tuned for another newsletter post!

Remember to check the Substack even when no newsletter comes out! I don’t send every post out to the mailing list. But if you want to keep up with me, check the site regularly. For example, I offered some reflections on my experience at Effective Altruism Global – 10 years after being banned from the event – a few days ago. Going forward, I’m going to publicly renew my commitment to sending at least two newsletters out each week.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: The Simple Heart

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a