|

|

For decades, the television political ad was king. Not since the mailpiece had candidates been able to beam their faces — and now their voices — directly into voters’ homes.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first candidate to broadcast a TV ad for political office: a 60-second cartoon spot set to his campaign song We Like Ike, produced by Roy O. Disney and Disney volunteers. At the time, just 40% of Americans owned a TV. Compared to Adlai Stevenson’s 30-minute televised speeches, Eisenhower’s ad was catchier, shorter, and far more appealing, helping him win with 55.2% of the vote and a 353-vote Electoral College margin.

And thus, the political TV ad war began. For 15, 30, or 60 seconds, candidates could speak directly to voters through their TV sets — a practice we’ve kept alive for 72 years.

That’s 72 years of the same tactic — which is still younger than 19 sitting members of Congress. Democrats, in particular, cling to an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mindset. But in the past 25 years, the media environment has been shifting under our feet. Using a tactic from 1952 in 2025 isn’t just stale — it’s a liability.

I’ve spent about a decade working in digital paid media for Democratic and progressive campaigns, and I can tell you: we are still having the same internal fights we had years ago.

We’ve seen proof that new media works:

Obama’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns used Facebook and other social media to activate young voters in unprecedented numbers.

Trump weaponized Twitter and fringe platforms to mobilize a nontraditional coalition of Republicans and alt-right activists.

Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez raised millions in small-dollar donations through email and digital ads alone.

And yet, Democrats — and some of their most trusted consultants — still hesitate to put real money into digital.

They talk about “meeting people where they are,” but increasingly put resources into spaces where voters aren’t.

Instead of podcasts and streaming shows, they’re on Sunday political talk shows.

Instead of short-form video, they post Notes App screenshots.

Instead of targeted digital ads, they keep buying bulk broadcast TV.

Cord Cutting and the Need for the Youth Vote

Back in 2018, I co-wrote a piece at Revolution Messaging about how outdated tactics were excluding Millennials and Gen Z.

At the time, streaming represented 44.8% of TV viewership — roughly equal to cable and broadcast’s 44.1%.

Today, it’s not even close: 82% of Americans use streaming services, and only 36% have cable or satellite TV. Of that 36%, just 8% watch cable/satellite without streaming.

For younger voters, broadcast is irrelevant:

88% of 18–29-year-olds use streaming.

92% of 30–49-year-olds do.

Only 16% of 18–29-year-olds and 23% of 30–49-year-olds have cable or satellite.

Streaming has nearly doubled its share of TV viewership in just 7 years. So why doesn’t our media buying reflect that?

The 2024 campaign cycle was seen as the highest spending in any campaign cycle to date. Across Presidential and Congressional elections, Democrats spent $6.7 billion, Republicans spent $7.6 billion, and third-party candidates spent a little more than $500 million.

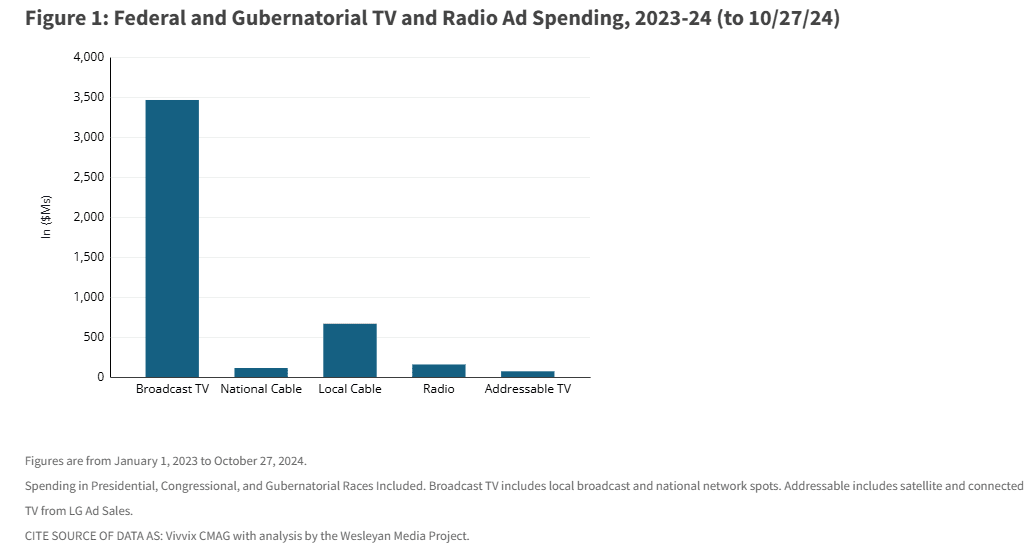

Between 2023 - 2024, Broadcast Television ads still accounted for the lion’s share of the ad buying. Broadcast TV accounted for 48% of Paid Media budgets, compared to 21% to CTV and 15% to Social Media, according to a report from Tech for Campaigns.

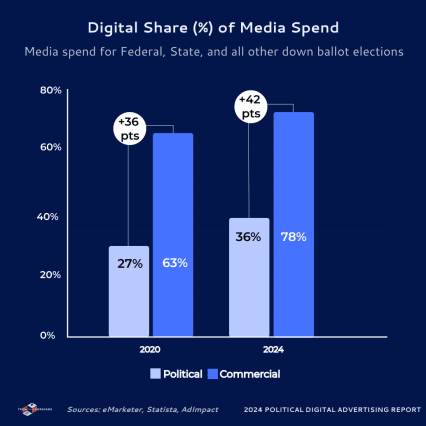

When compared to the commercial space, political advertising falls to only half of what commercial advertisers will spend on digital ads. Commercial ads spend 78% of their media budgets on Digital ads, where Political only spends 36%.

Towards the end of the 2024 cycle, campaigns began to increase their spending on Connected TV with video accounting for 76% of digital spending, but it only accounted for 24% of their total ad spend and by then it was too little too late.

The age old argument is that Democrats’ primary voting audience are older and therefore are consuming media by traditional means. But today, even older Americans are consuming content via streaming:

83% of Adults 50-64 watch streaming services

65% of Adults 65+ watch streaming services.

We can actually “reach people where they are” if we put the money to get our ads where more than 80% of people actually are.

We can actually “reach people where they are” if we put the money to get our ads where 80% of people actually are.

Wasted Spend and “District Leak”

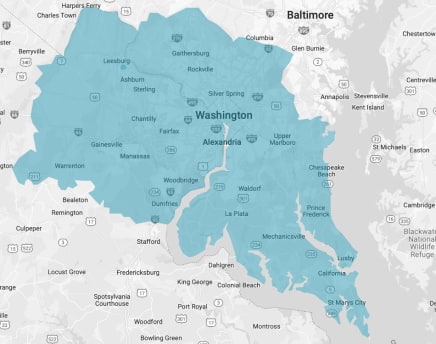

In the DC–Maryland–Virginia market, TV ads bleed across two states, one federal territory, 8 congressional districts, 41 state senate districts, and 70 state house districts. That means at least two-thirds of a broadcast buy is wasted on people who can’t vote for you.

In 2024, I saw ads at my gym (in VA-11) for races in VA-7, VA-10, MD-6, and Maryland’s U.S. Senate seat — all irrelevant to nearly everyone there.

State legislative and local candidates have it even worse. A delegate running in Arlington can end up buying ads that reach people in Hagerstown, Maryland — 72 miles away.

CTV and OTT eliminate this waste. You can target exact geographies, use voter file data, and frequency-cap so you’re not oversaturating. The Trade Desk estimates CTV campaigns reach households 36% more efficiently than linear TV.

Utilizing Programmatic CTV will not only get you onto people’s TV’s, but in a world where media is consumed on all sorts of devices, you can just as easily reach voters on their desktops, their tablets, and even their phones without having to guess when people are most likely to going to be watching TV. Your ads run when your targeted audience is online and consuming content making it so much more effective in knowing you are reaching active users rather than paying for a primetime slot and hoping people will be watching.

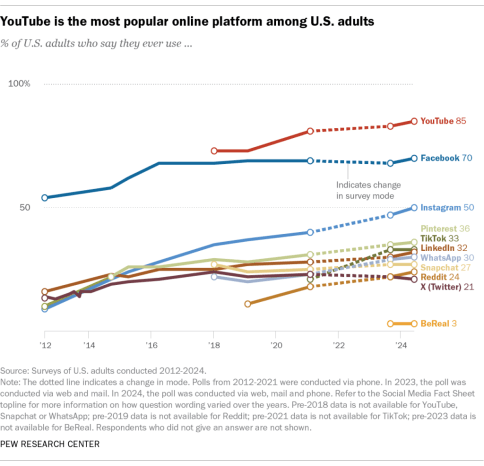

If campaigns insist on doing something broader than 1:1 targeting, then you know what is in more households than cable, satellite, and streaming combined? YouTube.

85% of all US adults use YouTube. More US adults today use YouTube than any other digital platform out there. That is true across all age ranges, even 65% of adults 65 and older use the video platform. 62% of all daily internet users are on YouTube.

Now, a large portion of those people do not use YouTube for politics. However, the vast majority of them also do not pay for Ad Free Premium YouTube, whereas the majority of users on Netflix, Hulu, Peacock, and other streaming services pay for the ad free version. If you want to mimic linear TV buying, just do it on YouTube. Your reach will be farther. Your geo will be smaller than the actual DMA so very few wasted impressions outside of your targeted area. You will actually be reaching people when they're online.

The Old Guard Problem

This would all be fine if we weren’t still letting yesterday’s playbook dictate today’s campaigns. The Democratic consulting class is dominated by firms founded in the early 2000s, still run by strategists who built their reputations after the Clinton years — and still advising from the same toolkit.

It’s why you still see CNN panels stacked with James Carville and Paul Begala to “diagnose” our electoral woes, even though their last big wins were decades ago. In their day, they were the risk-takers — the ones who convinced campaigns to throw out the rules. Axelrod and Plouffe were told in 2008 that relying heavily on the internet to elect a first-term senator from Illinois was political suicide. They proved the doubters wrong.

But now, those very pioneers have become the gatekeepers. They’re risk-averse, protective of broadcast-heavy budgets, and quick to warn candidates away from untested digital tactics. And because they’ve built decades-long trust with party leadership, their opinions carry outsized weight — even when they’re out of step with how voters actually consume media in 2025.

It’s a vicious cycle:

Veteran strategists recommend broadcast because it’s what they know.

Big-money candidates follow their lead to “play it safe.”

The results are underwhelming, and instead of rethinking the approach, the lesson drawn is “we need more of the same.”

Meanwhile, Republicans have been far more willing to test and adopt new channels — even ugly ones — if it means reaching their voters where they actually are. They’ve turned Facebook groups, YouTube channels, TikTok influencers, and meme pages into political infrastructure, while Democrats are still arguing about whether an ad on Hulu counts as “real TV.”

And that’s the other problem — by sticking with slow, traditional buys, we’ve ceded the agenda to the fringes of the internet. The right pushes “trans kids in sports” as the nation’s biggest issue, and instead of flooding feeds with our own priorities, too many Democratic campaigns either engage on their terms or ignore it entirely.

For instance, the fact that we let the Sydney Sweeney American Eagle ad campaign spin into a week-long fight over nothing is a symptom of a deeper problem in our media ecosystem. We often find ourselves asking, “Why does this even matter?” by the time the outrage cycle winds down. We’re so headstrong about being morally right and factually correct that we let fringe talking points dictate what we’re debating. That cedes ground to conservative influencers who can mock us one day for being “too sensitive” over a brand and championing the same sorority recruitment videos that they were once slutshaming “to own the Libs.” And still, we get pulled back into their outrage cycle — arguing with people who have no interest in being convinced.

By the time, we finally shift to our own agenda, it’s too late. In 2024, Democrats didn’t truly move serious resources into digital until Kamala Harris became the presumptive nominee. Down-ballot campaigns threw late money into Facebook and programmatic video in October, after months of letting the other side define the conversation.

You can’t keep letting everyone else dictate where the goalposts are. You can’t keep allowing others to bring you off the messaging track you are trying to set. You have to adapt to the new media environment. You have to start dominating the conversations.

There are bright spots — new firms, young strategists, and adaptive veterans who experiment constantly and treat digital as a first-tier tactic. But until we break broadcast’s grip and stop letting consultants from the 1990s steer 21st-century campaigns, we’ll keep fighting uphill battles in a media war we should be winning.

Democrats, Democratic strategists, and progressive consultants need to be bolder and braver when it comes to taking the leap to do new things. We cannot continue to rely on the playbook of Clinton Era politics to dictate how we can win, because just because something was successful a few years ago doesn’t mean it still will work. We have to adapt.

What Democrats Must Do

Lead with digital — not as an afterthought. 82% of Americans consume media this way.

Adapt to survive — the playbook from 30 years ago won’t work forever.

Be bold — take risks, test ideas, learn from failures.

Dominate the conversation — use digital to set the agenda, not react to it.

TL;DR

Democrats are still overspending on broadcast TV ads — a 72-year-old tactic — while voters, especially young ones, have long moved to streaming, YouTube, and other digital platforms. This outdated approach wastes money on audiences outside target districts and cedes the online conversation to the right, who dominate through faster, more nimble digital strategies. The “old guard” of Democratic consultants, stuck in Clinton-era playbooks, continues to resist bold digital investment, letting fringe outrage cycles (like the American Eagle ad drama) dictate what we talk about instead of driving our own priorities.

Bottom line: To win, Democrats must make digital the centerpiece of their media plans, target precisely, move faster, take risks, and seize control of the conversation — or risk falling even further behind.

By the Ballot is an opinion series published on Substack. All views expressed are solely those of the author and should not be interpreted as reporting or objective journalism or attributed to any other individual or organization. I am not a journalist or reporter, nor do I claim to be one. This publication represents personal commentary, analysis, and opinion only.