| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | What to Do Now With the Biggest Confederate Monument |

| Date | July 4, 2020 1:22 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[The largest celebration of the Confederacy should be obscured by

vegetation and the park outside Atlanta repurposed away from white

supremacy] [[link removed]]

WHAT TO DO NOW WITH THE BIGGEST CONFEDERATE MONUMENT

[[link removed]]

Ryan Gravel and Scott Morris

June 30, 2020

The Guardian

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ The largest celebration of the Confederacy should be obscured by

vegetation and the park outside Atlanta repurposed away from white

supremacy _

‘We have this fleeting opportunity to try to make it happen now,

and to tell our children we stood up to hate’ , Jessica

McGowan/Getty Images

The current national attention to the interrelated issues of policy

reform and representation

[[link removed]], along with

the murder [[link removed]] of

two Black men here in Georgia, got me thinking again about the

state’s giant monument to white supremacy on the side of Stone

Mountain

[[link removed]].

It is too big to just tear down, like they are doing with statues in

Richmond

[[link removed]] and

elsewhere, but something is going to happen with it eventually.

Anti-racist sentiment is growing, and the makeup of Georgia’s

population is changing so fast

[[link removed]] that

some kind of modification is inevitable. And while I believe decisions

about what ultimately happens there should emerge from meaningful

public engagement, I don’t believe we have to wait any longer to

make change. Below are some ideas we can start to implement now.

First, some context and history.

Stone Mountain is a massive geological aberration. Often incorrectly

identified as granite, the exposed rock is technically a “quartz

monzonite dome monadnock” that extends underground for miles in

every direction. The visible portion rises 1,686ft (514 meters) above

sea level, or 825ft above the surrounding Georgia piedmont.

Located 14 miles east of downtown Atlanta

[[link removed]], it sits within a

3,200-acre (1,294-hectare) forest-cum-theme-park that is owned by the

state of Georgia and managed by the Stone Mountain Memorial

Association. It is cited as “Georgia’s most visited attraction,

drawing nearly 4 million guests each year”. Best known for its

laser-light show that runs every night throughout the summer, the park

also offers hiking, fishing, camping, paddle boats, an excursion

train, a golf course, a Marriott conference center, educational

exhibits and a handful of memorials to white supremacy.

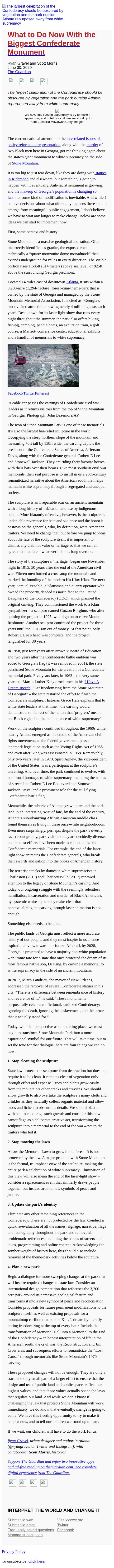

[A cable car passes the carvings of Confederate civil war generals as

it returns visitors from the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia.]

[[link removed]]

Facebook

[[link removed]]Twitter

[[link removed]]Pinterest

[[link removed]]

A cable car passes the carvings of Confederate civil war leaders as

it returns visitors from the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia.

Photograph: John Bazemore/AP

The icon of Stone Mountain Park is one of those memorials. It’s also

the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world. Occupying the steep

northern slope of the mountain and measuring 76ft tall by 158ft wide,

the carving depicts the president of the Confederate States of

America, Jefferson Davis, along with the Confederate generals Robert E

Lee and Stonewall Jackson. They are riding their favorite horses with

their hats over their hearts. Like most southern civil war memorials,

their real purpose is to instill in us a 20th-century romanticized

narrative about the American south that helps maintain white supremacy

through a segregated and unequal society.

The sculpture is an irreparable scar on an ancient mountain with a

long history of habitation and use by indigenous people. More

blatantly offensive, however, is the sculpture’s undeniable

reverence for hate and violence and the honor it bestows on the

generals, who, by definition, were American traitors. We need to

change that, but before we jump to ideas about the fate of the

sculpture itself, it is important to dismiss any claim of valor or

heritage so that we can all agree that that fate – whatever it is

– is long overdue.

The story of the sculpture’s “heritage” began one November night

in 1915, 50 years after the end of the American civil war. Fifteen men

burned a cross atop the mountain and marked the founding of the modern

Ku Klux Klan. The next year, Samuel Venable, a Klansman and quarry

operator who owned the property, deeded its north face to the United

Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), which planned the original

carving. They commissioned the work to a Klan sympathizer – a

sculptor named Gutzon Borglum, who after quitting the project in 1925,

would go on to carve Mount Rushmore. Another sculptor continued the

project for three years until the UDC ran out of money. At that point,

only Robert E Lee’s head was complete, and the project languished

for 30 years.

In 1958, just four years after Brown v Board of Education and two

years after the Confederate battle emblem was added to Georgia’s

flag (it was removed in 2001), the state purchased Stone Mountain for

the creation of a Confederate memorial park. Five years later, in 1963

– the very same year that Martin Luther King proclaimed in his I

Have A Dream speech,

[[link removed]] “Let

freedom ring from the Stone Mountain of Georgia!” – the state

restarted the effort to finish the Confederate sculpture. Historian

Grace Hale explains that to white state leaders at that time, “the

carving would demonstrate to the rest of the nation that

‘progress’ meant not Black rights but the maintenance of white

supremacy”.

Work on the sculpture continued throughout the 1960s while nearby

Atlanta emerged as the cradle of the American civil rights movement,

as the federal government passed landmark legislation such as the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, and even after King was assassinated in

1968. Remarkably, only two years later in 1970, Spiro Agnew, the

vice-president of the United States, was a participant at the

sculpture’s unveiling. And over time, the park continued to evolve,

with additional homages to white supremacy, including the names of

streets like Robert E Lee Boulevard and Stonewall Jackson Drive, and a

prominent role for the still-flying Confederate battle flag.

Meanwhile, the suburbs of Atlanta grew up around the park. And in an

interesting twist of fate, by the end of the century, Atlanta’s

suburbanizing African American middle class found themselves living in

these once-white neighborhoods. Even more surprisingly, perhaps,

despite the park’s overtly racist iconography, park visitors today

are decidedly diverse, and modest efforts have been made to

contextualize the Confederate memorials. For example, the end of the

laser-light show animates the Confederate generals, who break their

swords and gallop into the books of American history.

The terrorist attacks by domestic white supremacists in Charleston

(2015) and Charlottesville (2017) renewed attention to the legacy of

Stone Mountain’s carving. And today, our ongoing struggle with the

seemingly relentless humiliation, incarceration and murder of Black

Americans by systemic white supremacy make clear that contextualizing

the carving through laser animation is not enough.

Something else needs to be done.

The public lands of Georgia must reflect a more accurate history of

our people, and they must inspire in us a more aspirational view

toward our future. After all, by 2028, Georgia is projected to have a

majority non-white population – an ironic fate for a state that once

protested the dream of its most famous native son, Dr King, by carving

a memorial to white supremacy in the side of an ancient mountain.

In 2017, Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans, addressed the

removal of several Confederate statues in his city. “There is a

difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it,” he

said. “These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized

Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the

terror that it actually stood for.”

Today, with that perspective as our starting place, we must begin to

transform Stone Mountain Park into a more aspirational symbol for our

future. That will take time, but to set the tone for that dialogue,

here are four things we can do now:

1. STOP CLEANING THE SCULPTURE

State law protects the sculpture from destruction but does not require

it to be clean. It remains clear of vegetation only through effort and

expense. Trees and plants grow easily from the mountain’s other

cracks and crevices. We should allow growth to also overtake the

sculpture’s many clefts and crinkles as they naturally collect

organic material and allow moss and lichen to obscure its details. We

should blast it with soil to encourage such growth and consider this

new camouflage as a deliberate creative act, transforming the

sculpture into a memorial to the end of the war – not to the

traitors who led it.

2. STOP MOWING THE LAWN

Allow the Memorial Lawn to grow into a forest. It is not protected by

the law. A major problem with Stone Mountain is the formal, triumphant

view of the sculpture, making the entire park a celebration of white

supremacy. Elimination of this view will also mean the end of the

laser-light show – consider a replacement event that similarly draws

people together, but instead around new symbols of peace and justice.

3. UPDATE THE PARK’S IDENTITY

Eliminate any other remaining references to the Confederacy. These are

not protected by the law. Conduct a quick re-evaluation of all the

names, signage, narrative, flags and iconography throughout the park

and remove all problematic references, including the names of streets

and lakes, programming and online content. Acknowledging the somber

weight of history here, this should also include removal of the

theme-park activities below the sculpture.

4. PLAN A NEW PARK

Begin a dialogue for more sweeping changes at the park that will

inspire required changes to state law. Consider an international

design competition that refocuses the 3,200-acre park around its

namesake geological feature and transforms it into a new symbol of

peace and reconciliation. Consider proposals for future permanent

modifications to the sculpture itself, as well as existing proposals

for a mountaintop carillon that honors King’s dream by literally

letting freedom ring at the top of every hour. Include the

transformation of Memorial Hall into a Memorial to the End of the

Confederacy – an honest interpretation of life in the American

south, the civil war, the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, and

subsequent efforts to romanticize the “Lost Cause” through

memorials like Stone Mountain’s 1970 carving.

These proposed changes will not be enough. They are only a start, and

only small part of a larger effort to ensure that the design and use

of public land and public spaces reflect our highest values, and that

those values actually shape the laws that regulate our land. And while

we don’t know if challenging the law that protects Stone Mountain

will work immediately, we do know that eventually, change is going to

come. We have this fleeting opportunity to try to make it happen now,

and to tell our children we stood up to hate.

If we wait, our children will have to do the work for us.

_Ryan Gravel [[link removed]], urban designer and author in

Atlanta (@ryangravel on Twitter and Instagram); with

collaborator SCOTT MORRIS, historian_

_Support The Guardian and enjoy two innovative apps and ad-free

reading on theguardian.com. The complete digital experience from The

Guardian._

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

vegetation and the park outside Atlanta repurposed away from white

supremacy] [[link removed]]

WHAT TO DO NOW WITH THE BIGGEST CONFEDERATE MONUMENT

[[link removed]]

Ryan Gravel and Scott Morris

June 30, 2020

The Guardian

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

_ The largest celebration of the Confederacy should be obscured by

vegetation and the park outside Atlanta repurposed away from white

supremacy _

‘We have this fleeting opportunity to try to make it happen now,

and to tell our children we stood up to hate’ , Jessica

McGowan/Getty Images

The current national attention to the interrelated issues of policy

reform and representation

[[link removed]], along with

the murder [[link removed]] of

two Black men here in Georgia, got me thinking again about the

state’s giant monument to white supremacy on the side of Stone

Mountain

[[link removed]].

It is too big to just tear down, like they are doing with statues in

Richmond

[[link removed]] and

elsewhere, but something is going to happen with it eventually.

Anti-racist sentiment is growing, and the makeup of Georgia’s

population is changing so fast

[[link removed]] that

some kind of modification is inevitable. And while I believe decisions

about what ultimately happens there should emerge from meaningful

public engagement, I don’t believe we have to wait any longer to

make change. Below are some ideas we can start to implement now.

First, some context and history.

Stone Mountain is a massive geological aberration. Often incorrectly

identified as granite, the exposed rock is technically a “quartz

monzonite dome monadnock” that extends underground for miles in

every direction. The visible portion rises 1,686ft (514 meters) above

sea level, or 825ft above the surrounding Georgia piedmont.

Located 14 miles east of downtown Atlanta

[[link removed]], it sits within a

3,200-acre (1,294-hectare) forest-cum-theme-park that is owned by the

state of Georgia and managed by the Stone Mountain Memorial

Association. It is cited as “Georgia’s most visited attraction,

drawing nearly 4 million guests each year”. Best known for its

laser-light show that runs every night throughout the summer, the park

also offers hiking, fishing, camping, paddle boats, an excursion

train, a golf course, a Marriott conference center, educational

exhibits and a handful of memorials to white supremacy.

[A cable car passes the carvings of Confederate civil war generals as

it returns visitors from the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia.]

[[link removed]]

[[link removed]]Twitter

[[link removed]]Pinterest

[[link removed]]

A cable car passes the carvings of Confederate civil war leaders as

it returns visitors from the top of Stone Mountain in Georgia.

Photograph: John Bazemore/AP

The icon of Stone Mountain Park is one of those memorials. It’s also

the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world. Occupying the steep

northern slope of the mountain and measuring 76ft tall by 158ft wide,

the carving depicts the president of the Confederate States of

America, Jefferson Davis, along with the Confederate generals Robert E

Lee and Stonewall Jackson. They are riding their favorite horses with

their hats over their hearts. Like most southern civil war memorials,

their real purpose is to instill in us a 20th-century romanticized

narrative about the American south that helps maintain white supremacy

through a segregated and unequal society.

The sculpture is an irreparable scar on an ancient mountain with a

long history of habitation and use by indigenous people. More

blatantly offensive, however, is the sculpture’s undeniable

reverence for hate and violence and the honor it bestows on the

generals, who, by definition, were American traitors. We need to

change that, but before we jump to ideas about the fate of the

sculpture itself, it is important to dismiss any claim of valor or

heritage so that we can all agree that that fate – whatever it is

– is long overdue.

The story of the sculpture’s “heritage” began one November night

in 1915, 50 years after the end of the American civil war. Fifteen men

burned a cross atop the mountain and marked the founding of the modern

Ku Klux Klan. The next year, Samuel Venable, a Klansman and quarry

operator who owned the property, deeded its north face to the United

Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), which planned the original

carving. They commissioned the work to a Klan sympathizer – a

sculptor named Gutzon Borglum, who after quitting the project in 1925,

would go on to carve Mount Rushmore. Another sculptor continued the

project for three years until the UDC ran out of money. At that point,

only Robert E Lee’s head was complete, and the project languished

for 30 years.

In 1958, just four years after Brown v Board of Education and two

years after the Confederate battle emblem was added to Georgia’s

flag (it was removed in 2001), the state purchased Stone Mountain for

the creation of a Confederate memorial park. Five years later, in 1963

– the very same year that Martin Luther King proclaimed in his I

Have A Dream speech,

[[link removed]] “Let

freedom ring from the Stone Mountain of Georgia!” – the state

restarted the effort to finish the Confederate sculpture. Historian

Grace Hale explains that to white state leaders at that time, “the

carving would demonstrate to the rest of the nation that

‘progress’ meant not Black rights but the maintenance of white

supremacy”.

Work on the sculpture continued throughout the 1960s while nearby

Atlanta emerged as the cradle of the American civil rights movement,

as the federal government passed landmark legislation such as the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, and even after King was assassinated in

1968. Remarkably, only two years later in 1970, Spiro Agnew, the

vice-president of the United States, was a participant at the

sculpture’s unveiling. And over time, the park continued to evolve,

with additional homages to white supremacy, including the names of

streets like Robert E Lee Boulevard and Stonewall Jackson Drive, and a

prominent role for the still-flying Confederate battle flag.

Meanwhile, the suburbs of Atlanta grew up around the park. And in an

interesting twist of fate, by the end of the century, Atlanta’s

suburbanizing African American middle class found themselves living in

these once-white neighborhoods. Even more surprisingly, perhaps,

despite the park’s overtly racist iconography, park visitors today

are decidedly diverse, and modest efforts have been made to

contextualize the Confederate memorials. For example, the end of the

laser-light show animates the Confederate generals, who break their

swords and gallop into the books of American history.

The terrorist attacks by domestic white supremacists in Charleston

(2015) and Charlottesville (2017) renewed attention to the legacy of

Stone Mountain’s carving. And today, our ongoing struggle with the

seemingly relentless humiliation, incarceration and murder of Black

Americans by systemic white supremacy make clear that contextualizing

the carving through laser animation is not enough.

Something else needs to be done.

The public lands of Georgia must reflect a more accurate history of

our people, and they must inspire in us a more aspirational view

toward our future. After all, by 2028, Georgia is projected to have a

majority non-white population – an ironic fate for a state that once

protested the dream of its most famous native son, Dr King, by carving

a memorial to white supremacy in the side of an ancient mountain.

In 2017, Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans, addressed the

removal of several Confederate statues in his city. “There is a

difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it,” he

said. “These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized

Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the

terror that it actually stood for.”

Today, with that perspective as our starting place, we must begin to

transform Stone Mountain Park into a more aspirational symbol for our

future. That will take time, but to set the tone for that dialogue,

here are four things we can do now:

1. STOP CLEANING THE SCULPTURE

State law protects the sculpture from destruction but does not require

it to be clean. It remains clear of vegetation only through effort and

expense. Trees and plants grow easily from the mountain’s other

cracks and crevices. We should allow growth to also overtake the

sculpture’s many clefts and crinkles as they naturally collect

organic material and allow moss and lichen to obscure its details. We

should blast it with soil to encourage such growth and consider this

new camouflage as a deliberate creative act, transforming the

sculpture into a memorial to the end of the war – not to the

traitors who led it.

2. STOP MOWING THE LAWN

Allow the Memorial Lawn to grow into a forest. It is not protected by

the law. A major problem with Stone Mountain is the formal, triumphant

view of the sculpture, making the entire park a celebration of white

supremacy. Elimination of this view will also mean the end of the

laser-light show – consider a replacement event that similarly draws

people together, but instead around new symbols of peace and justice.

3. UPDATE THE PARK’S IDENTITY

Eliminate any other remaining references to the Confederacy. These are

not protected by the law. Conduct a quick re-evaluation of all the

names, signage, narrative, flags and iconography throughout the park

and remove all problematic references, including the names of streets

and lakes, programming and online content. Acknowledging the somber

weight of history here, this should also include removal of the

theme-park activities below the sculpture.

4. PLAN A NEW PARK

Begin a dialogue for more sweeping changes at the park that will

inspire required changes to state law. Consider an international

design competition that refocuses the 3,200-acre park around its

namesake geological feature and transforms it into a new symbol of

peace and reconciliation. Consider proposals for future permanent

modifications to the sculpture itself, as well as existing proposals

for a mountaintop carillon that honors King’s dream by literally

letting freedom ring at the top of every hour. Include the

transformation of Memorial Hall into a Memorial to the End of the

Confederacy – an honest interpretation of life in the American

south, the civil war, the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, and

subsequent efforts to romanticize the “Lost Cause” through

memorials like Stone Mountain’s 1970 carving.

These proposed changes will not be enough. They are only a start, and

only small part of a larger effort to ensure that the design and use

of public land and public spaces reflect our highest values, and that

those values actually shape the laws that regulate our land. And while

we don’t know if challenging the law that protects Stone Mountain

will work immediately, we do know that eventually, change is going to

come. We have this fleeting opportunity to try to make it happen now,

and to tell our children we stood up to hate.

If we wait, our children will have to do the work for us.

_Ryan Gravel [[link removed]], urban designer and author in

Atlanta (@ryangravel on Twitter and Instagram); with

collaborator SCOTT MORRIS, historian_

_Support The Guardian and enjoy two innovative apps and ad-free

reading on theguardian.com. The complete digital experience from The

Guardian._

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

* [[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web [[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions [[link removed]]

Manage subscription [[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org [[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV