Email

Lights, Action: Cut!

| From | Navigating Uncertainty (by Vikram Mansharamani) <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Lights, Action: Cut! |

| Date | August 3, 2025 11:01 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

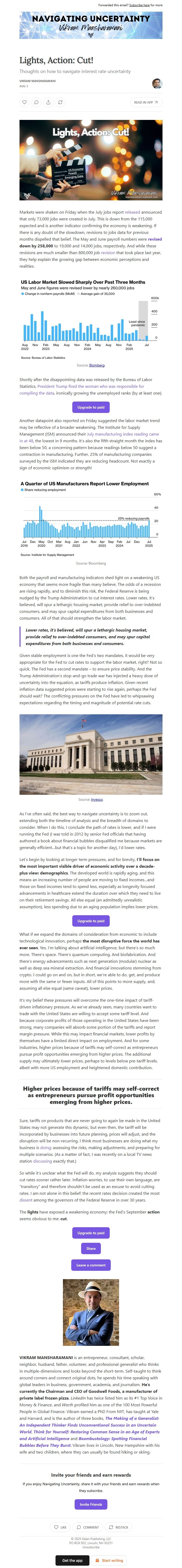

Markets were shaken on Friday when the July jobs report released [ [link removed] ] announced that only 73,000 jobs were created in July. This is down from the 115,000 expected and is another indicator confirming the economy is weakening. If there is any doubt of the slowdown, revisions to jobs data for previous months dispelled that belief. The May and June payroll numbers were revised [ [link removed] ] down by 258,000 to 19,000 and 14,000 jobs, respectively. And while these revisions are much smaller than 800,000 job revision [ [link removed] ] that took place last year, they help explain the growing gap between economic perceptions and realities.

Shortly after the disappointing data was released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, President Trump fired the woman who was responsible for compiling the data [ [link removed] ], ironically growing the unemployed ranks (by at least one).

Another datapoint also reported on Friday suggested the labor market trend may be reflective of a broader weakening. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) announced their July manufacturing index reading came in at 48 [ [link removed] ], the lowest in 9 months. It’s also the fifth straight month the index has been below 50, a concerning pattern because readings below 50 suggest a contraction in manufacturing. Further, 25% of manufacturing companies surveyed by the ISM indicated they are reducing headcount. Not exactly a sign of economic optimism or strength!

Both the payroll and manufacturing indicators shed light on a weakening US economy that seems more fragile than many believe. The odds of a recession are rising rapidly, and to diminish this risk, the Federal Reserve is being nudged by the Trump Administration to cut interest rates. Lower rates, it’s believed, will spur a lethargic housing market, provide relief to over-indebted consumers, and may spur capital expenditures from both businesses and consumers. All of that should strengthen the labor market.

Lower rates, it’s believed, will spur a lethargic housing market, provide relief to over-indebted consumers, and may spur capital expenditures from both businesses and consumers.

Given stable employment is one the Fed’s two mandates, it would be very appropriate for the Fed to cut rates to support the labor market, right? Not so quick. The Fed has a second mandate – to ensure price stability. And the Trump Administration’s stop-and-go trade war has injected a heavy dose of uncertainty into the equation, as tariffs produce inflation. Given recent inflation data suggested prices were starting to rise again, perhaps the Fed should wait? The conflicting pressures on the Fed have led to whipsawing expectations regarding the timing and magnitude of potential rate cuts.

As I’ve often said, the best way to navigate uncertainty is to zoom out, extending both the timeline of analysis and the breadth of domains to consider. When I do this, I conclude the path of rates is lower, and if I were running the Fed (I was told in 2012 by senior Fed officials that having authored a book about financial bubbles disqualified me because markets are generally efficient…but that’s a topic for another day), I’d lower rates.

Let’s begin by looking at longer term pressures, and for brevity, I’ll focus on the most important visible driver of economic activity over a decade-plus view: demographics. The developed world is rapidly aging, and this means an increasing number of people are moving to fixed incomes…and those on fixed incomes tend to spend less, especially as longevity focused advancements in healthcare extend the duration over which they need to live on their retirement savings. All else equal (an admittedly unrealistic assumption), less spending due to an aging population implies lower prices.

What if we expand the domains of consideration from economic to include technological innovation, perhaps the most disruptive force the world has ever seen. Yes, I’m talking about artificial intelligence, but there’s so much more. There’s space. There’s quantum computing. And biofabrication. And there’s energy advancements such as next generation (modular) nuclear as well as deep sea mineral extraction. And financial innovations stemming from crypto. I could go on and on, but in short, we’re able to do, get, and produce more with the same or fewer inputs. All of this points to more supply, and, assuming all else equal (same caveat), lower prices.

It's my belief these pressures will overcome the one-time impact of tariff-driven inflationary pressure. As we’ve already seen, many countries want to trade with the United States are willing to accept some tariff level. And because corporate profits of those operating in the United States have been strong, many companies will absorb some portion of the tariffs and report margin pressure. While this may impact financial markets, lower profits by themselves have a limited direct impact on employment. And for some industries, higher prices because of tariffs may self-correct as entrepreneurs pursue profit opportunities emerging from higher prices. The additional supply may ultimately lower prices, perhaps to levels below pre-tariff levels, albeit with more US employment and heightened domestic contribution.

Higher prices because of tariffs may self-correct as entrepreneurs pursue profit opportunities emerging from higher prices.

Sure, tariffs on products that are never going to again be made in the United States may not generate this dynamic, but even then, the tariff will be incorporated by businesses into future planning, prices will adjust, and the disruption will be non-recurring. I think most businesses are doing what my business is doing [ [link removed] ]: assessing the risks, making adjustments, and preparing for multiple scenarios. (As a matter of fact, I was recently on a local TV news station discussing [ [link removed] ] exactly that.)

So while it’s unclear what the Fed will do, my analysis suggests they should cut rates sooner rather later. Inflation worries, to use their own language, are “transitory” and therefore shouldn’t be used as an excuse to avoid cutting rates. I am not alone in this belief: the recent rates decision created the most dissent [ [link removed] ] among the governors of the Federal Reserve in over 30 years.

The lights have exposed a weakening economy; the Fed’s September action seems obvious to me: cut.

VIKRAM MANSHARAMANI is an entrepreneur, consultant, scholar, neighbor, husband, father, volunteer, and professional generalist who thinks in multiple-dimensions and looks beyond the short-term. Self-taught to think around corners and connect original dots, he spends his time speaking with global leaders in business, government, academia, and journalism. He’s currently the Chairman and CEO of Goodwell Foods, a manufacturer of private label frozen pizza. LinkedIn has twice listed him as its #1 Top Voice in Money & Finance, and Worth profiled him as one of the 100 Most Powerful People in Global Finance. Vikram earned a PhD From MIT, has taught at Yale and Harvard, and is the author of three books, The Making of a Generalist: An Independent Thinker Finds Unconventional Success in an Uncertain World [ [link removed] ], Think for Yourself: Restoring Common Sense in an Age of Experts and Artificial Intelligence [ [link removed] ] and Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst [ [link removed] ]. Vikram lives in Lincoln, New Hampshire with his wife and two children, where they can usually be found hiking or skiing.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Markets were shaken on Friday when the July jobs report released [ [link removed] ] announced that only 73,000 jobs were created in July. This is down from the 115,000 expected and is another indicator confirming the economy is weakening. If there is any doubt of the slowdown, revisions to jobs data for previous months dispelled that belief. The May and June payroll numbers were revised [ [link removed] ] down by 258,000 to 19,000 and 14,000 jobs, respectively. And while these revisions are much smaller than 800,000 job revision [ [link removed] ] that took place last year, they help explain the growing gap between economic perceptions and realities.

Shortly after the disappointing data was released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, President Trump fired the woman who was responsible for compiling the data [ [link removed] ], ironically growing the unemployed ranks (by at least one).

Another datapoint also reported on Friday suggested the labor market trend may be reflective of a broader weakening. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) announced their July manufacturing index reading came in at 48 [ [link removed] ], the lowest in 9 months. It’s also the fifth straight month the index has been below 50, a concerning pattern because readings below 50 suggest a contraction in manufacturing. Further, 25% of manufacturing companies surveyed by the ISM indicated they are reducing headcount. Not exactly a sign of economic optimism or strength!

Both the payroll and manufacturing indicators shed light on a weakening US economy that seems more fragile than many believe. The odds of a recession are rising rapidly, and to diminish this risk, the Federal Reserve is being nudged by the Trump Administration to cut interest rates. Lower rates, it’s believed, will spur a lethargic housing market, provide relief to over-indebted consumers, and may spur capital expenditures from both businesses and consumers. All of that should strengthen the labor market.

Lower rates, it’s believed, will spur a lethargic housing market, provide relief to over-indebted consumers, and may spur capital expenditures from both businesses and consumers.

Given stable employment is one the Fed’s two mandates, it would be very appropriate for the Fed to cut rates to support the labor market, right? Not so quick. The Fed has a second mandate – to ensure price stability. And the Trump Administration’s stop-and-go trade war has injected a heavy dose of uncertainty into the equation, as tariffs produce inflation. Given recent inflation data suggested prices were starting to rise again, perhaps the Fed should wait? The conflicting pressures on the Fed have led to whipsawing expectations regarding the timing and magnitude of potential rate cuts.

As I’ve often said, the best way to navigate uncertainty is to zoom out, extending both the timeline of analysis and the breadth of domains to consider. When I do this, I conclude the path of rates is lower, and if I were running the Fed (I was told in 2012 by senior Fed officials that having authored a book about financial bubbles disqualified me because markets are generally efficient…but that’s a topic for another day), I’d lower rates.

Let’s begin by looking at longer term pressures, and for brevity, I’ll focus on the most important visible driver of economic activity over a decade-plus view: demographics. The developed world is rapidly aging, and this means an increasing number of people are moving to fixed incomes…and those on fixed incomes tend to spend less, especially as longevity focused advancements in healthcare extend the duration over which they need to live on their retirement savings. All else equal (an admittedly unrealistic assumption), less spending due to an aging population implies lower prices.

What if we expand the domains of consideration from economic to include technological innovation, perhaps the most disruptive force the world has ever seen. Yes, I’m talking about artificial intelligence, but there’s so much more. There’s space. There’s quantum computing. And biofabrication. And there’s energy advancements such as next generation (modular) nuclear as well as deep sea mineral extraction. And financial innovations stemming from crypto. I could go on and on, but in short, we’re able to do, get, and produce more with the same or fewer inputs. All of this points to more supply, and, assuming all else equal (same caveat), lower prices.

It's my belief these pressures will overcome the one-time impact of tariff-driven inflationary pressure. As we’ve already seen, many countries want to trade with the United States are willing to accept some tariff level. And because corporate profits of those operating in the United States have been strong, many companies will absorb some portion of the tariffs and report margin pressure. While this may impact financial markets, lower profits by themselves have a limited direct impact on employment. And for some industries, higher prices because of tariffs may self-correct as entrepreneurs pursue profit opportunities emerging from higher prices. The additional supply may ultimately lower prices, perhaps to levels below pre-tariff levels, albeit with more US employment and heightened domestic contribution.

Higher prices because of tariffs may self-correct as entrepreneurs pursue profit opportunities emerging from higher prices.

Sure, tariffs on products that are never going to again be made in the United States may not generate this dynamic, but even then, the tariff will be incorporated by businesses into future planning, prices will adjust, and the disruption will be non-recurring. I think most businesses are doing what my business is doing [ [link removed] ]: assessing the risks, making adjustments, and preparing for multiple scenarios. (As a matter of fact, I was recently on a local TV news station discussing [ [link removed] ] exactly that.)

So while it’s unclear what the Fed will do, my analysis suggests they should cut rates sooner rather later. Inflation worries, to use their own language, are “transitory” and therefore shouldn’t be used as an excuse to avoid cutting rates. I am not alone in this belief: the recent rates decision created the most dissent [ [link removed] ] among the governors of the Federal Reserve in over 30 years.

The lights have exposed a weakening economy; the Fed’s September action seems obvious to me: cut.

VIKRAM MANSHARAMANI is an entrepreneur, consultant, scholar, neighbor, husband, father, volunteer, and professional generalist who thinks in multiple-dimensions and looks beyond the short-term. Self-taught to think around corners and connect original dots, he spends his time speaking with global leaders in business, government, academia, and journalism. He’s currently the Chairman and CEO of Goodwell Foods, a manufacturer of private label frozen pizza. LinkedIn has twice listed him as its #1 Top Voice in Money & Finance, and Worth profiled him as one of the 100 Most Powerful People in Global Finance. Vikram earned a PhD From MIT, has taught at Yale and Harvard, and is the author of three books, The Making of a Generalist: An Independent Thinker Finds Unconventional Success in an Uncertain World [ [link removed] ], Think for Yourself: Restoring Common Sense in an Age of Experts and Artificial Intelligence [ [link removed] ] and Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst [ [link removed] ]. Vikram lives in Lincoln, New Hampshire with his wife and two children, where they can usually be found hiking or skiing.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a