Everyone loves enshittification. Not the thing itself, of course. But Cory Doctorow’s neologism was an instant hit, neatly encapsulating the public’s growing disappointment, sometimes bordering on rage, with what was happening to internet platforms. His pithy summary of the process was also brilliant:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

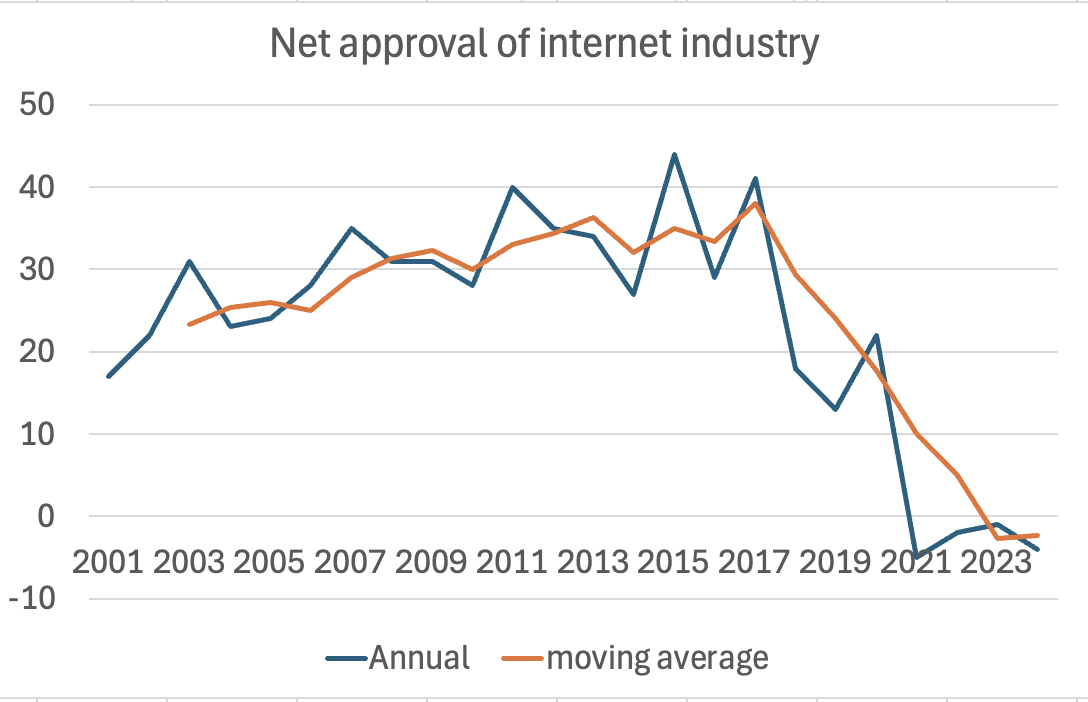

I argued earlier this week that enshittification has a lot to do with the way the tech industry has fallen out of public favor:

Source: Gallup

And the increasingly anti-democratic rage of tech bros is, I’d argue, in part driven by their awareness that people don’t love and admire them the way they used to, and their belief that they should still be the culture heroes they once were.

But without detracting from the brilliance of Doctorow’s discussion, I’ve become convinced that his analysis is too narrow, focusing only on certain kinds of social platforms. In fact, the basic logic of enshittification — in which businesses start out being very good to their customers, then switch to ruthless exploitation — applies to any business characterized by network effects. It may go under different names like “penetration pricing,” but the logic is the same.

Doctorow’s final stage — “Then, they die” — may also be wishful thinking.

So let me talk a bit about the economics of enshittification, as I see it, then follow up by talking about how enshittification can mess with our heads in several ways. The title of this post is, of course, facetious. I don’t have a general theory to offer, just some hopefully clarifying ideas.

Suppose you run a business whose product, whatever it may be, is subject to network effects: the more people using it, the more attractive it is to other current or potential users. Social media platforms like Facebook or TikTok are the currently obvious examples, but the logic works for services like Uber or physical goods like electric vehicles too.

What’s the profit-maximizing strategy for your business? The answer seems obvious: offer really good value to your customers at first, to build up the size of your network, then enshittify — soak the customer base you’ve built. The enshittification could take the form of charging higher prices, but it could also involve reducing quality, forcing people to watch ads, etc. Or it could involve all of the above.

As I said, this business strategy seems obvious, but I thought it would be a good idea to clarify my thinking by returning to my professional roots and writing down a little mathematical model. If you’re a normal human being I wouldn’t recommend reading this, but if you’re a masochist here it is:

A Simple Model Of Enshittification Download

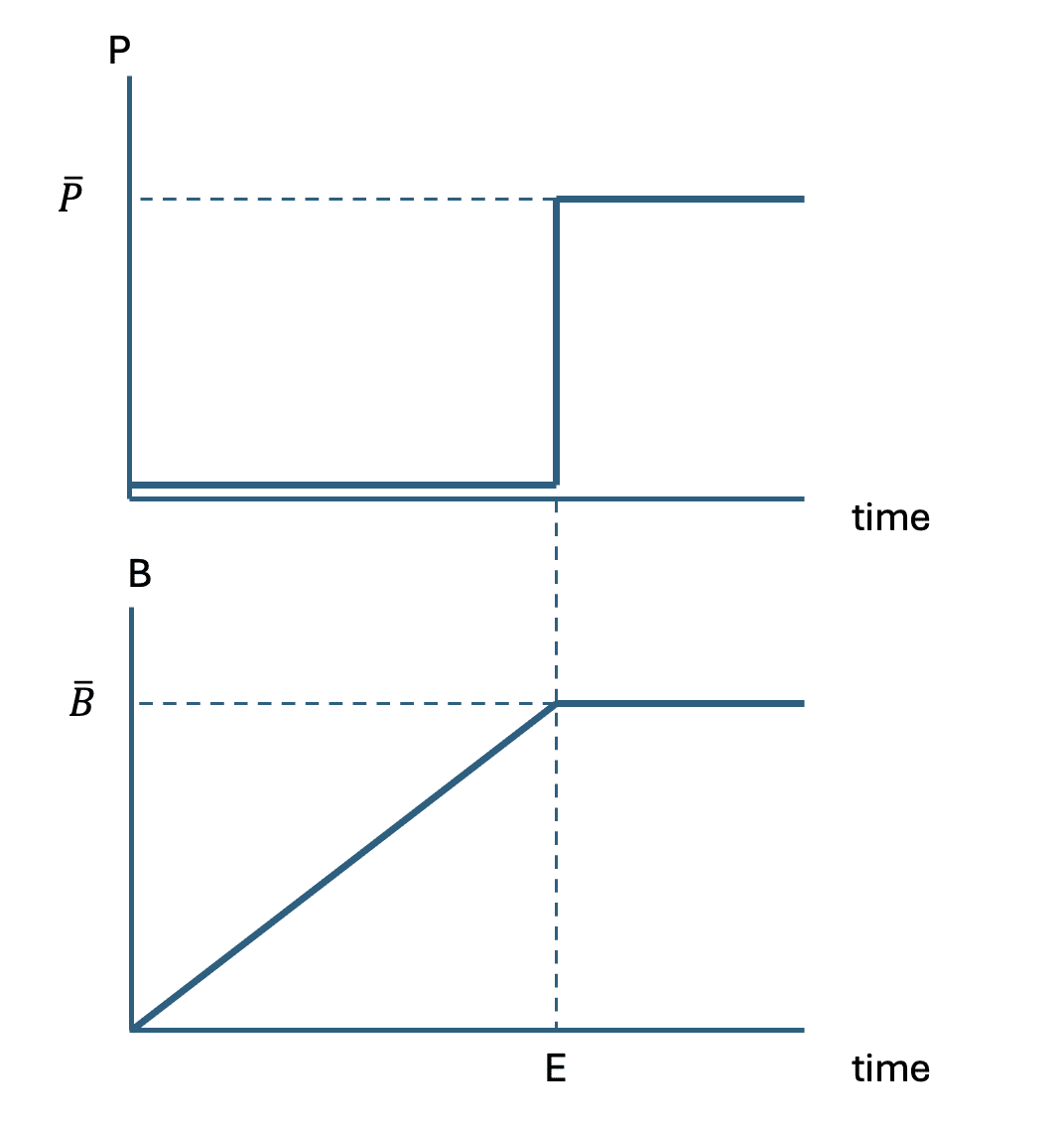

In my little model I don’t leave any room for degrading quality; enshittification takes place solely through higher prices. The model predicts the following paths for the price, P, and the customer base, B:

In this simplified, stylized model enshittification happens all at once, with a sudden jump in prices. It’s not hard to think of real-world reasons the process might be more gradual and stealthy — the ruthlessness might sneak up on customers rather than being revealed all at once. On the other hand, I was struck by Tuesday’s discussion of Uber in Bloomberg’s Odd Lots, and Uber’s move into profitability has been quite sudden:

Gotta say, “earnings inflection strategy” as a term for squeezing your customers — basically, enshittification — is a euphemism to be savored.

One last point: In my little model, the story doesn’t end with the firm dying. It ends, instead, with stagnation — the monopolist increases prices and/or reduces quality enough that his base stops growing, but not enough to drive it away. For what it’s worth, that appears to be the story so far for Facebook, whose user base has plateaued but not crashed. Twitter is a somewhat different story, but this post is about enshittification, not Nazification.

Side note: I don’t post on Facebook. I think I may have tried once many years ago, but if you see accounts claiming to be me, they’re impostors.

Anyway, to summarize: a history in which firms start out offering great stuff at low prices but eventually offer worse stuff at high prices is the natural life cycle for any industry with strong network effects. It’s the story of Facebook and Amazon. It’s also, I’m pretty sure, the story of the rise and fall of Peak TV.

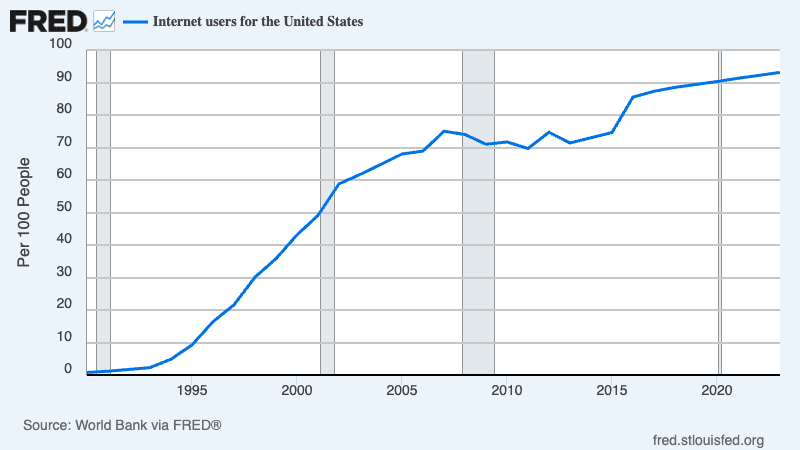

Why do such stories seem more widespread than in the past? Well, the internet isn’t the only source of network effects, but it does make them more likely. And the internet only really became pervasive during the 2000s:

Once almost everyone was using the internet, it became possible for businesses in a variety of areas to build up customer bases sustained by strong network effects. And one after another, these businesses have gone through the enshittification cycle.

That’s bad. Like everyone, I miss good service, good prices, and quality entertainment. But a further problem with enshittification is, as I said, that it messes with people’s heads.

For users, it’s all too natural to see the degradation of their experience as a morality play. Once upon a time, the fantasy goes, there were nice guys who ran their businesses in the public interest. Then, however, they became corrupt, or were forced to behave badly by venture capital, or something.

But they were never nice guys. Doctorow is good on this:

Now, the guy who ran Facebook when it was a great way to form communities and make friends and find old friends is the same guy who has turned Facebook into a hellscape. There’s very good reason to believe that Mark Zuckerberg was always a creep, and he took investment capital very early on, long before he started fucking up the service. So what gives? Did Zuck get a brain parasite that turned him evil? Did his investors get more demanding in their clamor for dividends?

As Tessio says in The Godfather, it was always “only business.”

The thing is, the enshittification cycle also messes with the heads of the people running these companies. They were loved when the public imagined, falsely, that they were the good guys. Now they aren’t. And it drives them crazy.

OK, I should talk about policy responses to enshittification. But this post is already too long, so I’ll come back to that another day.

I [Paul Krugman) am an economist by training, and still a college professor; my major appointments, with some interim breaks, were at MIT from 1980 to 2000, Princeton from 2000 to 2015, and since 2015 at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. I won 3rd prize in the local Optimist’s club oratorical contest when in high school; also a Nobel Prize in 2008 for my research on international trade and economic geography.

However, most people probably know me for my side gig as a New York Times opinion writer from 2000 to 2024. I left the Times in December 2024, and have mostly been writing here since.

Subscribe or upgrade subscription to Paul Krugman's Substack column.